2-page proposal file

advertisement

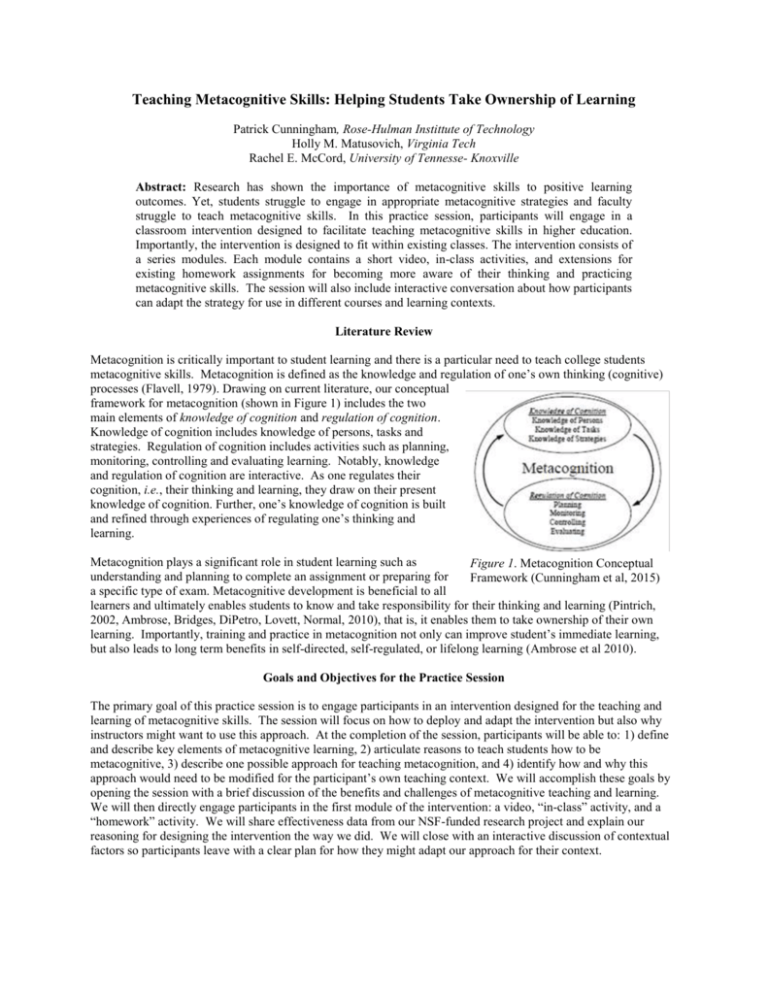

Teaching Metacognitive Skills: Helping Students Take Ownership of Learning Patrick Cunningham, Rose-Hulman Instittute of Technology Holly M. Matusovich, Virginia Tech Rachel E. McCord, University of Tennesse- Knoxville Abstract: Research has shown the importance of metacognitive skills to positive learning outcomes. Yet, students struggle to engage in appropriate metacognitive strategies and faculty struggle to teach metacognitive skills. In this practice session, participants will engage in a classroom intervention designed to facilitate teaching metacognitive skills in higher education. Importantly, the intervention is designed to fit within existing classes. The intervention consists of a series modules. Each module contains a short video, in-class activities, and extensions for existing homework assignments for becoming more aware of their thinking and practicing metacognitive skills. The session will also include interactive conversation about how participants can adapt the strategy for use in different courses and learning contexts. Literature Review Metacognition is critically important to student learning and there is a particular need to teach college students metacognitive skills. Metacognition is defined as the knowledge and regulation of one’s own thinking (cognitive) processes (Flavell, 1979). Drawing on current literature, our conceptual framework for metacognition (shown in Figure 1) includes the two main elements of knowledge of cognition and regulation of cognition. Knowledge of cognition includes knowledge of persons, tasks and strategies. Regulation of cognition includes activities such as planning, monitoring, controlling and evaluating learning. Notably, knowledge and regulation of cognition are interactive. As one regulates their cognition, i.e., their thinking and learning, they draw on their present knowledge of cognition. Further, one’s knowledge of cognition is built and refined through experiences of regulating one’s thinking and learning. Metacognition plays a significant role in student learning such as Figure 1. Metacognition Conceptual understanding and planning to complete an assignment or preparing for Framework (Cunningham et al, 2015) a specific type of exam. Metacognitive development is beneficial to all learners and ultimately enables students to know and take responsibility for their thinking and learning (Pintrich, 2002, Ambrose, Bridges, DiPetro, Lovett, Normal, 2010), that is, it enables them to take ownership of their own learning. Importantly, training and practice in metacognition not only can improve student’s immediate learning, but also leads to long term benefits in self-directed, self-regulated, or lifelong learning (Ambrose et al 2010). Goals and Objectives for the Practice Session The primary goal of this practice session is to engage participants in an intervention designed for the teaching and learning of metacognitive skills. The session will focus on how to deploy and adapt the intervention but also why instructors might want to use this approach. At the completion of the session, participants will be able to: 1) define and describe key elements of metacognitive learning, 2) articulate reasons to teach students how to be metacognitive, 3) describe one possible approach for teaching metacognition, and 4) identify how and why this approach would need to be modified for the participant’s own teaching context. We will accomplish these goals by opening the session with a brief discussion of the benefits and challenges of metacognitive teaching and learning. We will then directly engage participants in the first module of the intervention: a video, “in-class” activity, and a “homework” activity. We will share effectiveness data from our NSF-funded research project and explain our reasoning for designing the intervention the way we did. We will close with an interactive discussion of contextual factors so participants leave with a clear plan for how they might adapt our approach for their context. Description of the Practice Becoming more effective and efficient learner requires accurate awareness of how one processes information, what type of thinking specific learning tasks require, and multiple strategies for different learning tasks (Svinicki 2004, Weinstein, Acee, & Jung 2011). Further, successful learners consciously draw on and actively implement this knowledge during learning experiences. Developing these metacognitive skills and becoming an efficient and effective learner is not innate, but it does develop with focused attention, effort, and practice. This is most effective within specific learning contexts, that is, within classes as students are engaging with particular content (Kaplan, Silver, LaVaque-Manty, & Meizlish 2013). Therefore, we have designed this metacognitive intervention to fit within an existing course or learning context. Our intervention consists of a three interconnected elements implemented in series across an academic term. The elements include: 1) a short video (no more than five minutes long), designed to introduce an aspect of metacognition with a preliminary argument for its utility; 2) a short activity to be conducted in class, designed to help students translate theory to action for the specific course or learning context; and 3) a short homework assignment, designed to help students become more aware of their thinking and practice the metacognitive element in conjunction with an existing homework assignment. The elements are paired together within each of six modules to spur metacognitive development throughout an academic term. The videos are generic, that is, they are not specific to a particular course or learning context, and are aimed at students. They use analogies and personal stories to relate the concepts and the utility of metacognition for learning. Because the in-class modules and assignment extensions are particular to the course or learning context, they need to be modified for application in other contexts, and we will be providing guidance and support for doing so. We intentionally designed the interventions to be short as this was extremely important for our context; engineering instructors tend to resist teaching “non-technical” content and the engineering curriculum is already perceived to be overloaded (Shuman, Besterfield-Scare and McGourty, (2005). Discussion Consistent with current literature, preliminary findings from our study show that teaching students about metacognition will have positive impacts. In collecting the baseline data we used to design our intervention, we conducted interviews at the start and end of an academic term. At the start of the term we asked students how they planned to approach learning in the up-coming quarter. At the end of the term, we asked students how well they executed their plan and if it worked. We also showed interview participants a preliminary version of the first video. After seeing the video, students expressed enthusiasm for learning how they could better approach learning. They suggested moving the metacognition interventions earlier in the curriculum. At the end of the semester, one student remarked that she changed the way she thought about learning simply from having participated in the interview at the beginning of the quarter where she was introduced to metacognition and the potential benefits. References Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., Dipetro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Normal, M.K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Cunningham, P., Matusovich, H.M., Hunter, D.A.N., & McCord, R.E. (2015). Teaching metacognition: Helping engineering students take ownership of their learning. Proceedings- Frontiers in Education, El Paso, TX. Flavell, J.H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911. Kaplan, M., Silver, N., LaVaque-Manty, D, Meizlish, D. (Eds.) (2013). Using reflection and metacognition to improve student learning: Across the disciplines, across the academy. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Pintrich, P.R. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 219-225. Shuman, L.J., Besterfield-Sacre, M., & McGourty, J. (2005). The ABET “Professional Skills” – Can they be taught? Can they be assessed? Journal of Engineering Education, 94, 41-55. Svinicki, M. (2004). Learning and motivation in the postsecondary classroom. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing Company. Weinstein, C.E., Acee, T.W., & Jung, J. (2011). Self-regulation and learning strategies. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 126, 45-53.