The Garnet Bracelet and other stories

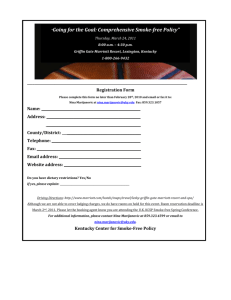

advertisement