Benedick's Soliloquy Analysis: Much Ado About Nothing

advertisement

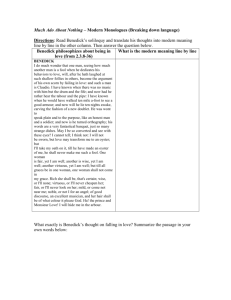

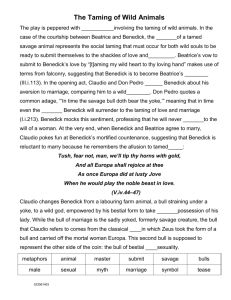

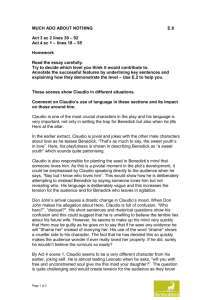

Analysis of Benedick’s Soliloquy (Act 2, Scene 3). The character of Benedick is established from his entrance in the first scene as a male chauvinistic joker. In this soliloquy, Benedick rants about the folly of love and how he will never be made a fool. Benedick’s ire is the result of his friend, Claudio, having fallen in love and gotten engaged to Hero. He had always assumed that Claudio felt the same way about love as he did and seems to feel betrayed by his “desertion.” Benedick sets up a list of comparisons between Claudio before he fell in love and the changes he now perceives in him; he and Claudio have recently returned from a war and Benedick’s descriptions are filled with military references. The first description contrasts “the drum and the fife” with “the tabor and the pipe,” a reference to Claudio’s change of personality from a serious disposition to a merrier, lighthearted nature; the change from the measured, marching beat to the exuberance of festival music. Benedick portrays this “new” Claudio as a fashion victim: “I have known when he would have walked ten miles afoot, to see a good armour, and now will he lie ten nights awake carving the fashion of a new doublet” In his life as a soldier, he was dedicated to practical considerations, but now he worries endlessly over his appearance in an effort to attract Hero. Benedick continues to add that Claudio’s speech has grown as elaborate as his dress; the imagery of the phrase “his words a very fantastical banquet” creates the impression that Benedick is overwhelmed by his language, as a diner might be when presented with a laden table. Also, “just so many strange dishes,” is an image that suggests Benedick fails to understand Claudio’s feeling, that the concept is alien to him or it could further imply just how at odds this new behaviour is to Claudio’s usual character. Claudio is supposed to be Benedick’s friend, but Benedick seems to have little respect for him. This is illustrated by his failure to refer to him by his name and instead dubbing him with the incongruous nickname: “Monsieur Love” in the final line of his soliloquy. This mockery does not take place openly, perhaps because he is aware that Claudio, as a count, out ranks him. Benedick also utilises imagery when describing his own attitude to love; “love may transform me to an oyster.” “Oyster” may be a reference to the typical image of lovers as moody and silent, a possible link to the modern English phrase “clam up.” Oysters also have sexual connotations as they are famed to act as an aphrodisiac. The image, however, is highly incongruous and typical of Benedick’s wit and deprecation of views he does not share. Another example of this is his reaction to Claudio’s first confession of his love for Hero: “That I neither feel how she should be loved, nor know how she should be worthy, is the opinion that fire cannot melt out of me: I will die in it at the stake.” Act 1, Scene 1, lines 171-3 1 Benedick seems to draw a parallel between love and illness, likening love to a disease. He lists the typically desired characteristics of women: beauty, intelligence and virtue, but only attributes one trait to each figurative woman. Each description is followed by the statement, “yet I am well,” meaning he is unmoved; he is not in love; he is immune. After he has so eloquently expressed his distaste for love up until this point, it seems rather strange that, at line 22, Benedick begins to describe his perfect woman. His idea of perfection is a kind of defence mechanism, measuring all women by an impossible ideal: “till all graces be in one woman, one woman shall not come in my grace.” “One woman” could imply that Benedick does enjoy brief liaisons with many women, but he is not prepared to devote his life to one. This is supported by earlier hint of Benedick’s character, for example in the first scene he jokes that Leonato is unsure of Hero’s paternity, to which he replies: “Signor Benedick, no, for then you were a child.” Act 1, Scene 1, line 80 His list of qualities that his perfect woman would possess is chauvinistic in the extreme; the order in which he names them signifies their importance. The first he mentions is her wealth: “rich she shall be, that’s certain,” making him appear shallow, though perhaps not to an Elizabethan audience. Other qualities include wisdom, virtue (virginity), beauty, a good-nature, nobility (titled) and talent. He seems to consider it a generous concession to add: “and her hair shall be of what colour it please God.” The irony is that is moments later Benedick, tricked by Don Pedro, Leonato and Claudio, is vowing to woo Beatrice, who falls somewhat short of some of his stipulations, when her hears of her supposed affection. The characters of Benedick and Beatrice are intellectual equals, though neither of them would admit it. It is this tempestuous nature of their relationship that provides most of the comedy in the play: “And they are not merely witty lovers, they are lovers who are wits.” From “Shakespeare and the Traditions of Comedy” - Leo Salingar, page 244 2 Bibliography: Shakespeare, William - Much Ado About Nothing Cambridge University Press, 1988 ______________________________ Salingar, Leo - Shakespeare and the Traditions of Comedy Cambridge University Press, 1974 3