How should historians approach and write about global and local

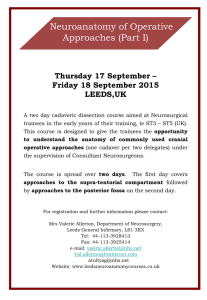

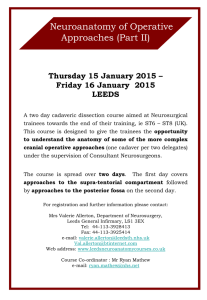

advertisement

ROBERT ALLERTON PARK: THE STORY OF A MAN, HIS CULTURAL SURROUNDINGS, AND THE ILLINOIS PRAIRIE By Andrew Ewald Fall 2004 History 498 Professor Hoganson 1 2 How should historians approach and write about global and local histories? A common trend in the study of world history has been a narrow concentration on city histories. For example, the book London 1900 by Jonathan Schneer focuses on London as an imperial metropolis, representative of world history. Can the narrative not be broadened to include local contexts? In contrast, local narratives have been highly intimate and nostalgic portrayals of local people and events. Often, local histories do not offer a broad discussion relating the locale to a global narrative. It is important to ask how the global context affects local histories and how local histories have shaped the global narrative. Both Donald Wright’s book, The World and a Very small Place in Africa, and Leon Fink’s book, The Maya in Morganton, show the value of linking local and global history. Wright concentrates on the effects of globalization upon Niumi, a small area in West Africa. As Kevin Reilly mentions in the book's forward, "Earlier generations of historians writing from the vantage point of the material metropolis often entertained the conceit that localities like London stood for the World.” In discussing Niumi in a global context, Wright includes local actors and is sensitive to their involvement in the larger narrative. Fink concentrates on a labor dispute at Case Farms chicken processing plant in Morganton, North Carolina. By 1995, eighty-percent of the plant’s employees were Spanish-speaking, the majority of which originated from Guatemala. According to Fink, the story highlighted “a demographic transformation of the U.S. labor force," which was especially apparent in North Carolina. In studying Morganton, Fink illustrates how the global context and the local context affected each other. Both examples show that perhaps local history is not entirely local and instead is impacted by and shapes world history. This paper’s underlying purpose is to examine Robert Allerton Park, located outside small-town Monticello, Illinois, as a local setting with global dimensions. Instead of simply 3 illustrating the park’s global links, I ask, why did this setting become a hybrid of the local landscape and art and design of foreign inspirations? I find that a larger culture filled with global to local links existed during Robert Allerton's time and place. Monticello is a small town in east-central Illinois with a population of approximately five thousand people. It is located roughly twenty-five miles southeast of Champaign-Urbana, home to the University of Illinois. Four miles to the southwest of Monticello lies 1,500 acres of land along the Sangamon River known as Robert Allerton Park. In addition to the estate are roughly 3,800 acres of farmland, which helps support park upkeep. Robert Allerton’s father, Samuel, gave the land to him when he was a child. Allerton moved to the “The Farms,” his name for the grounds, in 1896 and by 1900, he had built a Georgian mansion. Over the next forty-five years, "The Farms" developed into what is now Robert Allerton Park. Though he never married, Allerton received help with his creation from adopted son, John Wyatt Gregg, a University of Illinois architecture student whom he met in 1926. Robert Allerton began developing the park in 1914 with the goal of showing how art and nature could be combined for enjoyment and inspiration. Allerton, fond of Illinois’ landscape, carefully blended the statuary and ornaments with the prairie. While the designs of the park’s gardens were of foreign inspirations, native floral materials were used. This park on the prairie features native plants and wildlife, yet follows European garden design and is full of both foreign and foreign-influenced statuary, ornaments, and architecture.1 In 1946, Robert Allerton donated “The Farms” to the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Allerton stipulated that the land be an educational and research center; a forest, plant, and wildlife preserve; an example of landscape architecture; and a public park. In addition, a 4- 1 Jessie Borror Morgan, ed., The Good Life in Piatt County: A History of Piatt County, Illinois. (Moline, IL: Desaulniers & Company, 1968), pp. 243-249. 4 H Memorial Camp was established on the grounds.2 Today, the park averages over fifty thousand visitors per year, with all fifty U.S. states and every developed nation represented in its guest book. It offers the feel of an outdoor museum in which one can walk through and experience beauty from around the world. The art truly represents the entire globe from Europe to China. Popular attractions include The Sun Singer, a statue situated in an open meadow near the back of the park, the Chinese Fu Dogs, the Sunken Garden, and Antoine Bourdelle's sculpture, the Death of the Last Centaur.3 The secondary literature pertaining to Robert Allerton and the park has concentrated primarily on his wealth and privilege as well as the objects he collected. For example, Kay Bock's book, Majestic Allerton, focuses on Allerton's family and his creation of the park. Muriel Scheinman's section on Allerton Park in her book, A Guide to Art at the University of Illinois, focuses on the history of the park’s artwork. Also, current literature has briefly speculated as to why Robert Allerton dedicated himself to life as art and to the creation of his park. In Majestic Allerton, University of Illinois architectural historian Walter Creese speculates that Allerton's attraction to art was typical of his generation. He argues that the generation behaved in this way as a reaction to the harsh business practices of their fathers.4 But without personal statements from Allerton that exhibit such claims, they are hard to substantiate. Also, in her book, Bock tells the story of Isaac Allerton coming to America on the Mayflower. She portrays Isaac as a lifelong traveler and mentions that Walter Allerton, Robert's uncle, wrote in a family history in 1888, “The Allerton's have ever been wanderers.” While the statement certainly foreshadows the life Robert Allerton came to live, Bock goes on to speculate that, "Young Robert would have 2 Ibid., p. 243. “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens and Sculpture, Docent Training Reference.” 4 Kay Bock, Majestic Allerton: The Story of the Creation of an Oasis on the Prairie, (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Foundation, 1998), p. 10. 3 5 been 15 that year, an impressionable age that perhaps left him susceptible to his ancestor's influence." Certainly, stories of ancestors impacted Robert as he later made homage to Isaac’s grave.5 But through the course of Allerton family history, from Isaac to Robert, there were ancestors who did not enjoy the same prestige and wealth as Isaac. Isaac Allerton being an important figure in American history, a wealthy man, and a traveler does not mean all Allertons would live such a life. One cannot therefore imply that genealogy equals destiny. For good reasons, this paper will not attempt to apply concrete psychological theory to Allerton's life. It is not my purpose to develop a psychological biography of Robert Allerton. Famed developmental psychologist, Erik Erickson, also wrote psychological biographies of such influential figures as Gandhi. Such an undertaking requires a wealth of insight and statements made by the subject, which is beyond the reach and purpose of my current research. To try and create a psychological analysis of Allerton based on theory could potentially result in injustice to Robert Allerton and his life story. Instead, this paper will rely on the common knowledge that all individuals are influenced by their family context, or the lack thereof, as well as by their social and cultural contexts. It is certain that Robert Allerton was a man of wealth, prestige, and high culture, a traveler with natural leanings towards art and beauty. But to simply stop there and imply links between this picture of Allerton and his embodiment of world art does not do full justice to the story. Robert Allerton Park is not the result of a simple equation where wealth, privileges, and artistic leanings automatically equaled a park characterized by international linkages. Does the park represent something more than just wealth and travel? What the current secondary literature fails to fully examine is Robert Allerton's cultural and historical context. History has long been the study of "man" and his interaction not only with the physical environment but also 5 Ibid., p. 3. 6 his social and cultural environment. Robert Allerton Park reflects not only Allerton’s psychological makeup and familial status but his cultural surroundings as well. Socioeconomic status affects an individual’s views of society, what they are exposed to, and what is accessible. Thus, there is a relationship between one's status and the impact culture could potentially have upon him or her. Robert Allerton’s early cultural context was characterized by, among other things, an aesthetic movement, cosmopolitanism, and Orientalism as well as cultural events such as opera and the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. The vast majority of society was aware of these factors and certainly affected by them. However, working class families in 1893 with family members working long, hard hours to simply get by lacked the potential to interact with these movements and/or events compared to upper class families who enjoyed considerable leisure. The Allertons’ status meant more money and time to devote to culture. * * Samuel Allerton, born in 1828, an eighth generation descendent of Isaac Allerton, believed in hard work and staying close to the soil. As a young boy his family endured hardship after his father's business went bankrupt. Samuel watched as his mother sold her beloved horses and he vowed to one day be financially successful. Through persistent hard work at a young age Samuel was able to buy his father an eighty-acre farm. He then turned to trading livestock but finding success in the business took time. On one occasion he lost seven hundred dollars. However, Samuel was well aware that making money sometimes entails risks. His determination continued as moved west to Bloomington, Illinois, where he met Pamilla Thompson who became his first wife and the mother of Robert Allerton.6 After marrying, the couple moved to Chicago and Samuel, with a modest sum of money, 7 sought a new start. His experience with and knowledge of agricultural-business increased and in 1863 he took a risk that changed his life. With the Civil War underway and the Union Army in search of meat, Samuel instructed his uncle in Ohio to purchase contracts with the army that guaranteed delivery from Chicago. Samuel managed to borrow eighty thousand dollars and bought every hog that entered all eight of Chicago's stockyards for a day and half.7 The livestock were then delivered to the Union army and Samuel now had enough capital to expand his fortune. Along with other investors, Samuel formed the First National Bank of Chicago and soon thereafter he opened a much-needed central stockyard in Chicago. He went on to acquire 25,000 acres of land in Illinois, over 48,000 acres in Nebraska, and additional holdings in Ohio and Iowa. His stockyard interests extended to Omaha, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Jersey City. He built a mansion in Chicago, a summer home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and a winter home in California. He also went on to publish a book on the subject of practical farming in an attempt to boost production on family farms.8 As Bock states, "By the time of the Klondike Gold Rush in 1896, the Chicago Tribune declared Samuel the third richest man in Chicago. Only Marshall Field and Philip Armour had more wealth..."9 A family with a tradition of hard work and resulting wealth was the environment Robert Allerton was born into in 1873 and grew up surrounded by. The Allertons’ status can help explain the roots of Robert's devotion to art. Their wealth allowed for the embracing of culture with decorations, furnishings, travel, and entertainment of worldly scale. The Allerton Family Archives contain a receipt dated April 1896 from a jewelry 6 Ibid., pp. 4-5. Ibid., pp. 6-7. 8 “Oasis on the Prairie: The Legacy of Robert Henry Allerton,” 1996, VHS, University of Illinois Foundation. 9 Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 8. 7 8 store in Paris, France. There is also an envelope from May, 1896 from Samuel Allerton addressed to Mrs. S.W. Allerton in Paris.10 The Allerton's had the means to travel the world and experience all that they desired. Certainly, wealth was not the only reason Allerton decided to dedicate his life to art, but it is one important factor. Wealth propelled Robert into a life of art and allowed for the embrace of culture. In 1878, five-year-old Robert Allerton and his sister Kate contracted typhoid fever followed by scarlet fever two years later. Their mother Pamilla unfortunately caught the fever and died in 1880. In an act that displays the Allertons’ possibilities, Samuel sent his son and daughter to the Pulitzer Clinic in Switzerland for treatment, which somewhat cured Kate. However, the treatment left both Robert and Kate hard-of-hearing for the rest of their lives. (This explains Robert Allerton’s preference for small gatherings of people and the incorporation of only two guest bedrooms into the design of his mansion.) In 1882, Samuel married Agnes Thompson, Pamilla's younger sister, who as Bock says, "became the young boy's cultural mentor."11 Earlier as Robert's aunt and now as his stepmother, "it was she (Agnes) who kindled his interest in literature, music, gardening and visual arts.”12 A book in the family's archives, published in 1886 and written by George P. Upton entitled The Standard Operas, contains Agnes Allerton's nameplate on the inside cover. It is a collection of overviews of many operas from various countries including France, Italy, and Germany. The pages are full of penciled writings by Agnes, which note the operas she attended, when, and with whom. Dates of attendance range from the late 1880’s into the 1890’s. In some instances she wrote down who played which parts 10 Receipt, Folder: receipt, clippings, business cards, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, University of Illinois Archives. 11 Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 17. 12 Ibid., p. 17. 9 on the night she was present. Stuck between the pages of the book are various newspaper reviews or announcements of the operas attended.13 There is also a program for the Grand Opera, held at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago on December 9th 1891, along with various newspaper clippings. Four of these clippings consist of the opera schedule for weeks in early 1892. One opera was “Traviata,” which was performed in German, Italian, and French.14 The importance and attention Agnes gave to opera and her alleged role of cultural mentor is exhibited in the correspondence between Allerton and his secretary in Chicago, Helen Murphy, forty years later. Discussions of not only business, and the weather but also the opera fill these letters from late 1930's through the 1940's. Allerton served on the Board of Directors of the Chicago Civic Opera and Helen kept him up to date with the opera scene. After attending a performance she often mentioned how it compared to others she had seen. Helen urged Allerton on November 10, 1939 to travel to Chicago to attend the last performance of “Boris” for the season. She then wrote on November 21st that the “operas have been very high grade, much like those of years past… “Othello” will be another banner opera for me.” 15 Besides encouraging Robert’s love of opera, Agnes also encouraged him to attend classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and produce works of his own.16 His artistic leanings and cultural awareness are evident on the pages of his spelling book. The text, published in 1889 when Robert was sixteen, is entitled Hazen's Complete Spelling-Book. Written with pencil in the upper right hand corner of the first page is "Robert Allerton, Belmont School." Below is a sketch of a 13 Book, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, University of Illinois Archives. Folder: Opera Clippings and Program, Box 1, Ibid. 15 Folder: Robert Allerton and Helen Murphy Correspondence 1939-1940, Box 1, Ibid. 16 Arntzen, “Who Was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center, http://www.allerton.uiuc.edu/html/history.html. 14 10 woman in fashionable dress. Drawings similar to this are scattered throughout the book.17 All the drawings are of women and attention is given to their dresses. The orientation of the woman varies with each drawing as some are profiles, others are straight on, and a few are sitting. The clothes Robert has drawn on each vary as well. Some are wearing bonnets, some have their hair pulled up, and others have their hair drawn down. Robert gave quick detail to each outfit by drawing decorative items on each dress. The most interesting drawing is that of a woman adorned in what appears to be Egyptian clothing. The woman's eyes have been drawn in the fashion of ancient Egyptian art and she is wearing an Egyptian headpiece. While this may not be the true nature of the drawing, it does stand out from the others in terms of dress, which is certainly non-European and non-American.18 These drawings, made before Allerton acknowledges that he plans to dedicate his life to art, give insight into his early artistic leanings. Robert Allerton’s stepmother, Agnes, an opera aficionado, was his cultural guide. She opened Robert’s eyes to the culture of Chicago and America. Through travel Allerton experienced international societies firsthand. Agnes encouraged Allerton to produce artwork of his own and attend art classes. His sketch-littered spelling book illustrates his artistic tendencies and his cultural awareness. Years later, in 1929, Allerton funded and established the “Agnes Allerton Textile Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago,” in her memory.19 What was the culture that surrounded young Robert Allerton and that Agnes mentored to him? * * * In 1882, the year Allerton turned nine, eccentric playwright and poet, Oscar Wilde, came to America to lecture on aesthetics. The lecture series, originally expected to last four months, was extended to a two hundred and sixty day, one hundred and forty lecture tour. In between 17 18 Book, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, University of Illinois Archives. Ibid. 11 lectures, Wilde spent time visiting with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Walt Whitman. Wilde preached to his U.S. audiences about a living art and new truth that could transform their lives. Americans viewed Wilde as the leader of a new movement in art and beauty that had been gathering force in England and the United States in the preceding years. As the United States emerged from the Civil War and a history of bloody conflict, Americans began to turn to art and beauty as never before. In 1877, the country's education commissioner, John Eaton, commented that, "interest in all matters pertaining to art is more generally diffused throughout the community than at any former period of the history of the United States."20 Certainly, the beginnings of the movement can be traced to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. Though the fair was supposed to celebrate the nation's first century, concentration on wars and heroes were suppressed. As Wilde noted, the time had come for Americans to take a cultural position that differed from a concentration on heroes and battles of previous wars. United States culture had long valorized manly men. Wilde, touring America dressed in velvet robes with arched penciled-in eyebrows preaching aesthetics, was somewhat alarming to the masculinity of Victorian America. But America in general was ready for Wilde. He was marketable, and his tour was a great success. He reflected and embodied undercurrents of American culture and brought the aesthetic revolution to a new level. Aesthetics, as Wilde preached, was not simply a visual style but a consciousness as well. The embracing of art was noticeable everywhere, from household journals, to an increase in art schools and teachers, to a concentration on interior design. America was beginning to explore style, not as a form of 19 Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 20. Mary Warner Blanchard, Oscar Wilde’s America: Counterculture in the Gilded Age (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), p. xiii. 20 12 rebellion, but to create a new identity.21 The movement was far more pervasive than earlier movements in England. Not only were people passionate about art and beauty, but they also were interested in its production. Nowhere was this truer than in the design of interior domestic space. The beautification of interior space focused on consumption of international goods. As University of Illinois history professor, Kristin Hoganson, notes in her article “Cosmopolitan Domesticity: Importing the American Dream, 1865-1920,” “Through their households, these women strove to convey a cosmopolitan—meaning nationally unbounded—ethos.”22 Late nineteenth and twentieth century homes are examples of the intersection between the local and the global.23 Wealthy women, such as Agnes Allerton and Bertha Palmer, used their homes as a statement of their identity. Palmer’s Chicago mansion contained many theme rooms including a Spanish music room, an English dining room, a Moorish ballroom, and French and Chinese drawing rooms. Further, her bedroom was a replica of that found in an Egyptian palace.24 As my claims concerning Allerton suggests, this embrace of international style is not only a story of wealth and class. Cosmopolitan consumption was not reserved simply for the upper class, as middle class women worked with available resources to transform their homes into internationally inspired dwellings. Though they did not possess the money to hire an interior designer—a new profession gaining in popularity—they could afford to sift through the increasing abundance of magazines pertaining to the subject. The magazines, which had once concentrated on the Americanization of the household, now projected images of homes embellished with international inspiration and reprinted stories from European design magazines. 21 Ibid., p. 3. Kristin Hoganson, “Cosmopolitan Domesticity: Importing the American Dream, 1865-1920.” American Historical Review 107 (February 2002): 59. 23 Ibid., p. 57. 24 Ibid., p. 58. 22 13 British and French styles were most popular, however, Italian, Dutch, German, Norwegian, and other European styles were also praised. Americans, as never before, were also turning to the East as a source for consumption and inspiration. Oriental styles were not new to the country, but their existence thus far in American culture had been minimal. All of this changed as Orientalism swept across the nation during the last thirty years of the nineteenth century.25 An undated but early picture of Robert Allerton sitting at a desk reveals in the background a cabinet displaying Oriental figurines.26 John Gregg subscribed to Asia magazine in the 1930’s.27 Other oriental objects consumed by Americans included rugs, wall hangings, fans, and other ornaments. Women often erected “cozy corners,” a small niche in their home adorned with oriental furnishings. They often entailed, as Hoganson describes, “…an unupholstered divan, a profusion of cushions, a rug, a Turkish coffee table, some Orientalist…fans, screens, lanterns, and pottery, and lush draperies to frame the entire ensemble.”28 While the aesthetic movement in general reflects an America occluding its violent history, late nineteenth century cosmopolitan consumption reveals America’s position in the world. America was increasingly engaged in overseas affairs, as Hoganson mentions, “most notably through its commercial expansion, commitment to empire, and missionary impulses.”29 She further contends that “This engagement resulted in expanding geographic knowledge conveyed…through paintings, photographs, museums, missionary exhibits, immigrant enclaves, manufacturing displays, ethnographic and travel writings, and less obvious sources 25 Ibid., p. 62. Folder: Photograph, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, University of Illinois Archives. 27 Folder: John Gregg Correspondence 1936, Box 2, Ibid. 28 Hoganson, “Cosmopolitan Domesticity,” p. 71. 29 Ibid., p. 65. 26 14 including…household decoration magazines…”30 The many foreign exhibits of World’s Fairs, such as the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia and the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, captured this spirit. Americans also began to travel overseas and experience foreignness firsthand. As exemplified by the Allertons, overseas travel was still in large part a sign of wealth though an increasing number of Americans began to travel abroad. Overseas travels exposed tourists directly to foreign cultures and decorating styles. Often, travelers would purchase furniture or other ornaments to bring back and place in their homes. The travelers also brought back images and descriptions of overseas decorating practices. The majority of Americans without the means to travel abroad turned to various sources within the country to purchase foreign décor. As foreign imports increased dramatically between 1865 and the 1920’s, Americans found a plethora of global items to purchase. Catalogs and stores such as Vantines, an Oriental store with locations in Chicago and New York, offered imports. Magazines advised people to visit Chinatown for the best in Oriental goods. Also, immigrants looking to make a bit of money often sold family heirlooms. The World’s Fairs, upon closure, often sold items that had once been on display. People living in rural areas sometimes purchased goods from peddlers who traveled around the country.31 While Hoganson’s article and my recent discussion explain aestheticism and cosmopolitanism in terms of women’s domesticity, the movements were not entirely limited to women. Wilde’s visit and his message challenged traditional gender barriers and encouraged men to explore their feminine side. Some reporters who covered Wilde’s visit described him as manly with broad shoulders and the waist and hips of a man. However, others noted that there 30 31 Ibid. Ibid., p. 67. 15 was something womanish and unmanly about him, that he was at the very least a “mama’s boy.”32 Certainly, America had already begun feminizing itself to some degree as the old model of freedom fighter or citizen solider was replaced. As Mary Warner Blanchard contends in Oscar Wilde’s Visit to America, “Only a cataclysm as profound as a war between brother and brother could temporarily have suppressed the visibility and continuity of the soldier/hero in a culture formed from a revolutionary war ethos.”33 As war images and icons were being aestheticized, Wilde’s appearance in America introduced a new category to manhood.34 The aesthetic movement provided new feminine-type roles for men that went against Victorian notions of manliness. It was not just women who began designing interior space, but men also took to the practice. The painters, Tiffany and LaFarge, both switched to careers in interior design as other men began to design parlor screens and additional home furnishings.35 Men’s smoking rooms were often designed with Oriental furnishings and style. The architect Stanford White, known for his classical style, became fond of aesthetic interior designing.36 As Blanchard notes, it was American writers such as Mark Twain37 who “…created a mythical homosocial world in his novels, a refuge from women and feminine values.”38 Twain also noted homoerotic qualities in the rugged miners of the West. Some western miners cheered Oscar Wilde during his 1882 lecture tour. As Blanchard states, “He was seen as an aesthete (and possibly as a homosexual) but he was also, to a surprising degree applauded as ‘manly’.”39 The association of the aesthetic movement with homosexuality caused a backlash that contributed to the downfall of the movement by 1900. This did not, however, bring a complete end to Blanchard, Oscar Wilde’s America, p. xii. Ibid., p. 4. 34 Ibid., p. 10. 35 Ibid., p. xiv. 36 Ibid., p. 24. 37 Twain’s Hartford, Connecticut home, built in 1873, contained nineteen Tiffany-decorated rooms. 38 Blanchard, Oscar Wilde’s America, p. 19. 32 33 16 cosmopolitan consumption. As women began to shed their traditional Victorian clothes for foreign fashions or noncorseted dresses, men began experimenting with fashion. Photographer Fred Holland Day, associated with aesthetic style, often dressed in flowing Turkish robes. Men who visited Palestine Park in New York often wore oriental costumes. Popular architect Henry Hobson Richardson posed for a formal photograph in a medieval robe. Male costuming was certainly seen as artistic by society. A photograph featured in Majestic Allerton, is of a man and woman dressed in costume. The two are striking an artistic pose for the photographer as they flaunt their attire.40 At a 1981 Allerton Legacy symposium, John Gregg recalled the house parties that Allerton gave each spring. Friends from Chicago were joined by others from around the country and abroad, and a costume ball was one of the entertainment features. Allerton had collected a wide variety of costumes, which he stored in a small gallery off the dining room. Guests chose their own costumes from the costume room that included, among others, Roman togas and Japanese kimonos Allerton had collected.41 In 1893, Allerton, along with his best friend, artist Frederick C. Bartlett, was pledging his life to the creation of beauty. After attending Harvard Academy in Chicago, Allerton and Bartlett were sent to St. Paul’s college-prep school in Concord, New Hampshire. However, they decided instead to study art in Europe.42 During their summer return to Chicago in 1893, Allerton and Bartlett attended The World’s Columbian Exposition. From April to October of 1893, Chicago hosted the most famous World’s Fair ever held 39 Ibid., p. 27. Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 16. 41 Morgan, ed., The Good Life in Piatt County, p. 244. 42 Arntzen, “Who was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. 40 17 on American soil. The World’s Columbian Exposition celebrated the four hundredth year anniversary of Columbus’ voyage to America. The fairgrounds, covering over two square miles, was larger than any previous fair. It was three times as big as the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris and displayed the newly invented Ferris Wheel as its main attraction. As William Cronon states in his book, Nature’s Metropolis, “an army of artist, builders, and laborers under the direction of Chicago architect Daniel Burnham drained the swampy soil of Jackson Park…and created a lagoon that gave formal aesthetic unity to the main exhibition buildings.”43 There was the Agriculture, Machinery, Transportation, Liberal Arts, and Fine arts buildings among others. As Cronon describes, “into these temples of intelligence and industry they poured representative inventions and treasures from around the world…thirty six nations and forty six American states and territories built exhibits to display their contributions to civilization…”44 Visitors to the fair hailed from around the globe and across social classes with the final attendance totaling almost twenty-eight million individuals. Upon arrival at the fair, patrons were greeted with a “panorama of enormous proportions.”45 The northern one hundred acres contained the buildings sponsored by U.S. states and territories. Each was designed to reflect the character of its respective state in architecture, interior design, and collection and arrangement of display.46 In the center of the state buildings was the North Pond, which was fronted by the Fine Arts Building, one of the fair’s Great Buildings.47 The generally speaking Roman-style building featured a huge nave and lighted transept one hundred feet wide and seventy feet tall. “In the center was an enormous dome William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1992), pp. 341-342, p. 342. 44 Ibid., p. 342. 45 Norman Boltin and Christine Laning, The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 (Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 1992), p. 29. 46 Ibid., p. 32. 47 The building is the only structure from the fair still standing. Today, it is the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. 43 18 topped by a colossal statue, Victory, a figure poised upon a globe with outstretched arms offering laurel wreaths.”48 The statue reflects the nature of the building and captures the spirit of cosmopolitanism. The interior featured sculpture and painting from the United States and foreign countries. A mile of space was set aside for paintings, and France received around eighty thousand square feet of wall space.49 Nearly every European country displayed paintings in the exhibit. The works ranged from oil paintings and watercolors, to paintings on ivory, enamel, metal, and porcelain. There were engravings and etchings, prints, and chalk and pastel drawings. There were also Japanese paintings on silk, and carvings produced on ivory, wood, and metal. The vast collection of sculptures ranged in material from marble to bronze. Also on display were examples of the world’s finest architecture.50 In his autobiography, Allerton’s friend, Frederick Bartlett, commented on his and Allerton’s visit to the fair. He told of their “wild excitement” upon seeing the miles of European pictures. He mentions that they then vowed “to pledge their lives to the creation of beauty.”51 Continuing south from the Fine Arts Building were the Foreign Buildings, surrounded by lawns, walks, and beds of flowers and shrubbery ornamented with statues. France, Norway, Germany, Spain, Great Britain, India, Russia, and Japan among others erected buildings. These structures, like the State Buildings, reflected through architecture and interior displays, characteristics of the country. The Japanese invested more money into the fair than any other foreign participant. Their foreign building measured forty thousand square feet and contained a garden complex. They also occupied ninety thousand square feet of display space in the Great Building.52 In addition was a pavilion, the Ho-o-den, modeled after an eleventh century temple. Boltin and Laing, The World’s Columbian Exposition, p. 34. Ibid., p. 34. 50 Ibid., p. 80. 51 As quoted in, Arntzen, “Who Was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. 52 Boltin and Laing, The World’s Columbian Exposition, pp. 122-125. 48 49 19 As John Findling mentions in his book, Chicago’s Great World’s Fairs, the structure was “a major influence in the architectural development of Frank Lloyd Wright, then a young Chicago architect just beginning his own practice.”53 For most, a trip to the World’s Columbian Exposition was the experience of a lifetime. The Columbian Exposition represented, like cosmopolitanism, America’s emergence as a world power. Further, the fair coincided with and reflected the aesthetic, cosmopolitan, and Oriental movements. The vast amount of international goods on display at the fair certainly had a profound impact on those who sought to decorate their homes with foreign objects. A History of Chicago author, Bessie Pierce, believed the Columbian Exposition began a new epoch in the aesthetic growth of not only Chicago but of the Midwest and the entire nation.54 To claim the fair started the aesthetic movement discredits the effects of the Philadelphia Exposition of 1877 and Oscar Wilde’s 1882 lecture tour and ignores the attention given to the beautification of interior space. America’s concentration on aesthetics had long since begun. Author, Harry Thurston Peck wrote concerning the fair, “the importance…lay in the fact that it revealed to millions of Americans whose lives were necessarily colorless and narrow, the splendid possibilities of art, and the compelling power of the beautiful.”55 Though the fair certainly revealed the possibilities of art and beauty, the millions of Americans who witnessed it were, as shown, not entirely narrow and colorless. However, an increase in the formation of art clubs and study groups, and literary and cultural societies was evident following the fair. Beyond boosting nationalism, the fair coincided with, reinforced, and reflected the aesthetic, cosmopolitan, and Oriental movements. For those who had not been influenced by the movements, as profoundly John Findling, Chicago’s Great World’s Fairs, (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press,1994), p. 26. Reid Badger, The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition and American Culture (Chicago: NelsonHall Inc.,), pp. 114-115. 55 As quoted in, Ibid., p. 115 53 54 20 as others, the fair perhaps exposed them to and propelled them into arts, beauty, and foreignness. And for those like Frank Lloyd Wright and Robert Allerton, the fair reaffirmed and further influenced their artistic desires. At the end of the summer of 1893, Allerton and Bartlett returned to Europe to continue their studies. They studied at the Royal Academy of Bavaria in Munich, graduating in the spring of 1896. That fall they continued studying at teaching-studios in Paris. According to the Robert Allerton Park website, “Bartlett recalled that they studied drawing in the morning at Ecole Collin, painting in the afternoon at Ecole Aman-Jean, and in the evening they had a nude class with Carlo Rossi.”56 Allerton also studied at the Academie Julien in Paris. These European institutions preached to Robert, as Wilde had on his lecture tour, that all of life is art. However, Allerton decided he was not capable of developing a career in art, destroyed his paintings, and returned to Chicago. He soon decided to move to “The Farms” with the initial goal of becoming a gentleman farmer. Allerton, however, had not lost his artistic and cosmopolitan spirit. * * * * Allerton, like the planners of the Columbian Exposition who created a showcase of the United States and the World out of a swamp, quickly began developing the prairie landscape of “The Farms.” Allerton’s concerns were not limited simply to the aesthetics of the grounds as farm production was highly important. Under his supervision, “The Farms” eventually amounted to some twelve thousand acres of farmland. He employed dependable, hard-working farm foremen and was regarded by his tenants as a good landlord. As Kay Bock states, “thanks to his father’s teachings, coupled with his own good sense and the invaluable guidance of John Phalen, the farm foreman,” Allerton’s land yielded twice that of neighboring farms.57 While 56 57 As quoted in, Arntzen, “Who Was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 12. 21 farm production was important to Allerton, developing the land was his primary interest. As American overseas travel was increasing and with cosmopolitanism spreading, Allerton in 1881, at age eight, received for Christmas a book entitled ZigZag Journeys in Europe.58 Travel became one of Robert’s passions. Samuel’s funeral in 1914 was postponed nearly a month due to Robert being in Russia.59 A letter from Allerton to Helen Murphy in August of 1939 appears on stationary from the Grand Hotel Continental in Munich, Germany. Allerton’s book collection also highlights the extent of his travels. The books range in subject matter from history to horticulture, and from the arts and travel, to novels. Books, such as Robert Felix Hichen’s Three Years in a Life, in which the nameplate reads “R.H. Allerton, London, February 1, 1903,” alerts one to Allerton’s whereabouts at that time.60 But books were not all Allerton acquired on overseas travels. He collected artwork and gained artistic inspiration that he brought home to the Illinois prairie. Before developing the landscape of “The Farms,” Allerton’s first built a home. Around 1900, Americans began to view the English country house as the architectural ideal. Allerton hired Philadelphia architect, John Borie, whom he met in Paris to design his home. During the winter of 1888-1889, Allerton and Borie toured Europe in search of inspirations. They returned with a design that most closely resembled Ham House, the seventeenth century home of the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale, located just outside London on the Thames. The stone exterior, modified H plan, and the long gallery of Ham House were imitated in Borie’s design. Architectural historian, Walter Creese, has noted that the house is, generally speaking, representative of English-Edwardian architecture, but the grand staircase resembles those in 58 Folder: Susan Enscore Inventory of Allerton Library, 1 of 4, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, Univeristy of Illinois Archives. 59 Bock, Majestic Allerton, p. 19. 60 Folder: Susan Enscore Inventory of Allerton Library, 1 of 4, Box 1, The Allerton Family Collection, University of Illinois Archives. 22 American Colonial homes.61 However, the Park’s docent guide states that the stairs are the “progeny of the European palace staircase, perhaps ultimately derived from the staircase of honor at Versailles.”62 The home also features some English-Georgian style inspirations. Two sphinxes constructed from limestone as well as a reflecting pond lie at the home’s courtyard entrance. While in Europe, Allerton and Borie also purchased furnishings for the home. The Butternut Room on the first floor consists of native wood paneling and a chimney surround similar to those Borie designed for London interiors. The gallery contained Sheraton, Chippendale, or Louis XV furniture pieces pushed against the walls in traditional seventeenth century gallery fashion. The first floor music room (currently the library) is reminiscent of the Great Halls of medieval and Renaissance Britain. The room was originally adorned in Flemish tapestries, but they were replaced in 1929 by a jungle frieze painted by Frederick Bartlett. French, English, Italian, German, and Austrian furniture adorned the space. 63 While abroad, Allerton and Borie also collected ideas for landscaped gardens. The gardens of Ham House—their design, use of shrubbery, and ornamental statues—closely resembled areas of Allerton’s gardens. At the time of the home’s construction trees were planted and an English meadow was developed. After Borie moved to England in the early 1900’s, Allerton continued to develop the park. He created a series of formal gardens and collected ornamental statuary. During the 1920’s and 1930’s Allerton and John Gregg traveled to Europe, the Far East, and the Pacific Islands. They purchased works of art and continued to find creative inspiration for the park. Allerton became increasingly fascinated with Oriental art and philosophy. His art preferences also changed from Edwardian to modern, according to the park’s 61 62 Arntzen, “Who Was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens and Sculpture, Docent Training Reference.” 23 website, “one is reminded of the differences between the art and architecture of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition and the 1933 Century of Progress.”64 Though Allerton’s tastes changed his overall aesthetic focus and cosmopolitan purchases continued. One of the more notable statues of the park is a cast of Swedish sculpture Carl Milles’ Sun Singer. Allerton saw the original on the Stromparterre overlooking the Stockholm harbor in 1929. He visited Milles’ studio and commissioned him to create a reduced size replica. However, due to translation difficulties, the statue Allerton received was identical to the fifteen foot original. Milles’, commissioned by the Swedish Academy of Sciences to honor native poet Esaias Tegner, found inspiration for the piece from a poem by Tegner entitled “Song to the Sun.” The statue is of a young, nude Apollo standing with arms outstretched to the sky. John Gregg with Allerton’s approval placed the statue on a wide circular stone base surrounded by low shrubbery in a circular meadow enclosed by forest at the west end of the park. The Altar of Heaven in Peking, China provided inspiration for the stone base and the landscaping. Milles later commented on the setting saying, “I hope this bronze will stay there in that way till the last man has gone—when the earth is as dead as the moon—and still this is there.”65 Located in a circular clearing in the forest at the intersection of four paths and surrounded by white oak trees is the sculpture, Death of the Last Centaur, by French artist Emile-Antoine Bourdelle. The original statue, which symbolizes the death of paganism, was sculpted in 1914. Allerton purchased this bronze cast (with embedded gold flakes) from Bourdelle’s Paris studio in 1927. According to Muriel Scheinman, Bourdelle was “regarded by many of his contemporaries as the greatest sculptor of his generation.”66 Arntzen, “Who Was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. Ibid. 65 Scheinman, A Guide to Art, pp. 129-130, as quoted on p. 130. 66 Ibid., pp. 127-128. 63 64 24 The Garden of the Fu Dog’s with its mythological lion-dog statues illustrates Allerton’s admiration of Oriental art. Commonly utilized in Asian cemeteries and temples as Buddhist guardian figures to ward off evil spirits, their features combine those of Pekingese pug dogs and longhaired lion dogs. Allerton purchased twenty-two Fu Dogs in pairs from European and American art dealers and arranged them in a garden setting. Though the details of each ceramic statue differ, they are similar in overall size and look and as Scheinman states, “they may well have been made for the export in the same factory.”67 The Garden of the Fu Dogs consists of two rows, each containing eleven dogs evenly spaced on stone pedestals, which create a center pathway. Beyond each row of Fu Dogs are spruce trees and at one end of the pathway is a garden house—the House of the Gold Buddhas. Ornamental cast iron from New Orleans, dating back to the nineteenth century and most likely made in France, adorns the structure. Located inside are two gold Siamese Buddhas brought from Bangkok and a stone statue from Cambodia of the Brahmin god, Hari-Hara.68 The Sunken Garden, the last in the park’s series of formal gardens, also displays Oriental influence. The site was originally a ravine used as a catchall for compost, however, in 1915 Allerton began to develop the area. After several transformations, it was completed in 1932 based on John Gregg’s design. The garden-- a sunken, oval, amphitheatre made from concrete with Canadian hemlock around the upper terrace—displays Balinese influence.69 Atop pylons on each end of the garden are casts of Japanese guardian fish, known as “shachi,” made by Yamanka and Company in Tokyo in 1931. They are reduced scale versions of originals found at the seventeenth century Nagoya Castle in Japan.70 Before construction of the Sunken Garden, 67 Ibid., p. 132. “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens and Sculpture, Docent Training Reference.” 69 Arntzen, “Who was Robert Allerton,” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center website. 70 Scheinman, A Guide to Art, pp. 125-126. 68 25 the Chinese “Maze” Garden marked the end to the series of formal gardens. While often called a maze garden, it is unlike a traditional maze garden where one can get lost due to plant material growing above eyesight. The garden actually consists of a low hedge pattern based on the Chinese character for longevity found on a pair of Allerton’s collected silk pajamas (costume).71 Countless other statuary and gardens adorn the estate. The Triangle Parterre Garden features intricate triangle hedge patterns and evergreen plantings along with a variety of annual and perennial plants. Two pairs of Assyrian-style limestone lions situated upon pillars at each entrance of the garden were commissioned in 1922. The Walled or Brick Garden, designed by Borie in 1902, served as a vegetable garden for many years. Osage Orange trees and Espalier Pear trees outline the garden’s walls. (The term espalier refers to a tree that has been trained to grow against a wall or trellis.)72 The statue, Girl with a Scarf, serves as the garden’s focal point. Allerton purchased the four-foot cast cement sculpture, created by German artist Lili Auer, from the Chicago Art Institute in 1941. It was the last piece he acquired for the estate, and as Scheinman states, it is “an agreeable addition conforming in every way to the aesthetic Allerton established early in his years of collecting outdoor sculpture…”73 Four years earlier, in 1937, Allerton had bought one hundred twenty five acres on the island of Kauai, Hawaii. John Gregg designed a home, and the two of them moved there in 1938. Up until his generous donation to the University of Illinois in 1946, Allerton gradually spent less time at “The Farms”—the creative masterpiece of his youth. He passed away in 1964 at the age of ninety-one. * * * * * Robert Allerton’s father, Samuel, achieved his goal of providing a comfortable financial foundation for his family. Allerton family wealth allowed for immense possibilities for 71 72 “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens and Sculpture, Docent Training Reference.” “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens and Sculpture, Docent Training Reference.” 26 consumption, travel, and the embrace of culture. Early on, Agnes Allerton was Robert’s cultural guide, opening his young eyes to the arts. The culture Agnes mentored and Robert later indulged in was not, however, a culture reserved for the wealthy. Twenty-eight million people, including Allerton, from home and abroad and spanning the socioeconomic strata visited The Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Allerton’s creative vision for the Illinois prairie landscape is analogous with the ideas of those who conceptualized the World’s Fair. However, whereas the fair perhaps smothered visitors in aesthetic grandeur and cosmopolitanism, Allerton carefully combined visual arts and internationalism into the prairie landscape. The Fair captured the spirit of aesthetic undercurrents of American life, which can be traced back to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. Oscar Wilde’s aesthetic lecture tour in 1883 portrayed a United States culture suppressing its traditional war and soldier/hero model. Americans turned to visual arts and beauty and Allerton developed into a true aesthete. Americans, Allerton included, began engaging in cosmopolitan consumption at home and through overseas travel. A concentration on the beautification of interior space transpired, but Allerton was more concerned with exterior space—the Illinois prairie. He went a step further, as Scheinman states, “in Robert Allerton’s conception of his house and gardens, aesthetic considerations came before any others, and sculpture served the outdoors much in the same way that fine tapestries or porcelain animate and adorn an interior.”74 After settling at “The Farms,” Allerton nurtured an intimate relationship with the Illinois landscape he so greatly admired—designing gardens, collecting foreign ornamental statuary, and delicately blending it all into the native surround. Robert Allerton’s gift to the University of Illinois has left a lasting impact on all who 73 74 Scheinman, A Guide to Art, p. 111. Scheinman, A Guide to Art, p. 100. 27 have visited it—perhaps for a conference, or to study his statuary and landscape architecture, or to enjoy leisurely strolls within its boundaries. As Allerton intended, it is a place to enjoy nature and beauty at once. By approaching the story of Robert Allerton Park as a locale within a larger global narrative, I have expanded upon the accomplishments of the current secondary literature. A new dimension to the story has been revealed—a new avenue to be even further explored. The story of the creation of Robert Allerton Park is not just of a man and the physical environment but his cultural surroundings as well—a society fascinated with the arts, beauty, and foreignness. Robert Allerton Park reflects not only Allerton’s wealth, artistic leanings, and the extent of his travels, but also late nineteenth century United States’ cultural trends. 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY Allerton Family Collection. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Archives. 5 Boxes. Arntzen, Etta. “Who Was Robert Allerton.” Robert Allerton Park and Conference Center. http://www.allerton.uiuc.edu/html/history.html. Badger, Reid. The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition and American Culture. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall Inc., 1979. Blanchard, Mary Warner. Oscar Wilde’s America: Counter Culture in the Gilded Age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998. Bock, Kay. Majestic Allerton: The Story of the Creation of an Oasis on the Prairie. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Foundation, 1998. Boltin, Norman, and Laning, Christine. The World’s Columbian Exposition: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 1992. Cronon, William. Natures Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1991. Findling, John. Chicago’s Great World’s Fairs. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1994. Fink, Leon. The Maya of Morganton. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. Hoganson, Kristin. “Cosmopolitan Domesticity: Importing the American Dream, 1865-1920.” American Historical Review 107 (February 2002): 55-83. Morgan, Jessie Borror, ed. The Good Life in Piatt County: A History of Piatt County, Illinois. Moline, IL: Desaulniers & Company, 1968. Scheinman, Muriel. A Guide to Art at the University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign, Robert Allerton Park, and Chicago. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1995. Schneer, Jonathan. London 1900: The Imperial Metropolis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001. “The Farms: Mansion, Gardens, Sculpture. A Docent Training Reference.” University of Illinois Robert Allerton Park. n.d. University of Illinois Foundation, “Oasis on the Prairie: The Legacy of Robert Henry Allerton,” 1996. Video Recording. 29 Wright, Donald. The World and a Very Small Place in Africa: A History of Globalization in Niumi, The Gambia. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2004.