Handout

advertisement

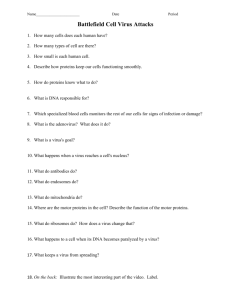

BB20023/0110: DNA & disease 2005-06 Oncogenic viruses Outline DNA viruses Herpesviridae (, HHV8/Kaposi’s sarcoma, Epstein-Barr virus) Papovaviridae (human papilloma virus – HPV) Hepadnaviridae (hepatitis B virus-HBV) RNA viruses Flavivridae (hepatitis C virus) Retroviridae ( Human T-cell lymphotropic virus –HTLV type I) Overview of viral replication EBV -Epstein-Barr virus Epstein–Barr virus is the most potent transforming agent, widespread in all human populations, and is usually carried as an asymptomatic persistent infection. In a small minority of infected individuals the virus is associated with the pathogenesis of certain types of lymphoid and nonlymphoid cancers, including Burkitt lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin disease and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). BL and NPC have geographically restricted distributions, with BL found in young children in the central Africa, while NPC is found predominantly in the southern coastal region of China. Hodgkin disease has been associated with EBV infection without a clear aetiological role. EBV is also associated with a number of lymphoproliferative diseases, which are mainly of B-cell origin. Replication and Latency: Virus infection involves two cellular compartments: (1) B cells, where infection is predominantly latent and has the potential to induce growthtransformation of infected cells; and (2) epithelial cells, where infection is predominantly replicative. EBV immortalises B-cells, the main mediator of primary and persistent infection. Primary EBV infection is usually followed by latency, but in immunodeficiency, the proliferation of cells can proceed unchecked. Following primary infection of B cells, a chronic virus carrier state is established in which the outgrowth of EBV-transformed B cells is controlled by an EBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response re-activated from a pool of virus-specific memory T cells. At certain sites, latently infected B cells can become permissive for lytic EBV infection. Infectious virus released from these cells can be shed directly into the saliva or might infect epithelial cells and other B cells. In this way a virus-carrier state is established that is characterised by persistent, latent infection in circulating B cells and occasional EBV replication in B cells and epithelial cells Dr. MV Hejmadi 0023: DNA: making, breaking & disease Transformation: The virus enters B cells by interaction of the major viral glycoprotein gp350/220 with the complement receptor (CR2/CD21, an immunoglobulin superfamily member). This complex mediates an interaction between EBV and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, which serve as a co-receptor for virus entry into B cells. Once the viral genome has been uncoated and transferred to the nucleus, circularisation and transcription from the Wp promoter begin a cascade of events leading to expression of all the latent genes. The EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA) leader protein (EBNA-LP) and EBNA2 are the first proteins to be expressed and these are sufficient to advance the cells to early G1 phase of the cell cycle. The EBV-infected (EBV+) cells begin to proliferate in a manner that depends on high cell density and on the autocrine production of cytokines that promote B-cell growth. Later, the EBV+ cells evolve into cells that grow more rapidly and are less dependent on autocrine growth mechanisms. Following infection in vivo, the virus establishes a latent infection in memory B cells and this is characterised by the limited expression of a subset of virus latent genes. Role of Epstein–Barr virus in the pathogenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma In both nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive gastric carcinoma, the tumour cells carry monoclonal viral genomes, which indicates that EBV infection must have occurred prior to expansion of the malignant cell clone.. Multiple genetic changes have been found in NPC, with frequent deletion of regions on chromosomes 3p, 9p, 11q, 13q and 14q and promoter hypermethylation of specific genes on chromosomes 3p (RASSF1A and retinoic-acid receptor 2) and 9p (genes that encode INK4A, INK4B, ARF and death-associated protein kinase). Deletions in both 3p and 9p in low-grade dysplastic lesions and in normal nasopharyngeal epithelium from individuals who are at high risk of developing NPC in the absence of EBV infection, indicate that genetic events occur early in the pathogenesis of NPC and that these might cause predisposition to subsequent EBV Dr. MV Hejmadi 0023: DNA: making, breaking & disease infection.The above scheme (see figure; images show stained epithelial sections) has been proposed, in which loss of heterozygosity (LOH) occurs early in the pathogenesis of NPC, possibly as a result of exposure to environmental cofactors such as dietary components (such as salted fish). This results in low-grade pre-invasive lesions that, after additional genetic and epigenetic events, become susceptible to EBV infection. Once cells have become infected, EBV latent genes provide growth and survival benefits, resulting in the development of NPC. Additional genetic and epigenetic changes occur after EBV infection. CIS, carcinoma in situ; EDNRB, endothelin receptor B; H/E, staining with haematoxylin and eosin; TSLC1, tumour suppressor in lung cancer 1. HPV human papilloma virus These viruses cause lower genital tract cancers; most commonly cervical cancer. Since HPVs replicate in stratified epithelial cells only, they are the aetiological agents of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) at various sites. Some of the high risk HPVs in cancer are HPV16, 18, 31 & 33. Genome: HPV has a small circular genome of approximately 8 kbp and the mRNA is transcribed off one strand of the DNA by host cell RNA polymerase II. There are five early genes coding for proteins, which are involved in DNA replication (E1 and E2) or activation of cell growth (E6, E7 and E5), and three late genes, two of which code for the major and minor capsid proteins (L1 and L2, respectively) and one of unknown function (E4). Like most of the tumour viruses, the cell/growthactivating proteins affect either the signal transduction pathways or cell cycle control. Replication: During the malignant phase of the disease, when the lesion is confined to the epithelium, the viral DNA is in an episomal form, and amplification of the genome and viral particle production occurs in the upper parts of the epithelium. In malignant cells, the genome is integrated randomly in over 70% of cases, while in the rest there are episomal copies. All malignant cells continue to express E6 and E7 proteins, suggesting that these proteins are essential for maintenance of the malignant phenotype. Cancer transformation: The transforming activity of HPV16 is associated with mainly E6 and E7 proteins and some from E5. E6 and E7 are multifunctional proteins that can increase cell proliferation and survival by several pathways. E.g. E6 binds to the E6-associated protein (E6-AP) and p53 (tumour suppressor) in a heterotrimeric complex. The result of this binding is the premature degradation of p53 through the ubiquitin pathway. E6-AP is in fact a ubiquitin protein ligase. Since one of the functions of p53 is to control the passage of cells through the G1 phase of the cell cycle, any abrogation of this activity could lead to uncontrolled cell cycle progression. E7 binds to the retinoblastoma family of tumour suppressor proteins, RB, p107 and p130. Normally, late in G1 RB is phosphorylated, and this releases transcription factors such as E2F, important for DNA synthesis. E7 can cause this same release of factors in the absence of RB phosphorylation and drive cells into unregulated S phase. E7 has also been shown to bind the AP-1 family of transcription factors and bind/compete with histone deacetylase for binding to RB. HBV- hepatitis B virus HBV is one of the aetiological agents of hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). There is a higher incidence of HCC in regions endemic to HBV infection contracted neonatally with persistence. In USA and northern Europe, infection usually occurs in adulthood and persistence occurs in approximately 1–10% of infected individuals. There is now a successful vaccine consisting of the surface antigen (HBsAg) of the virus, which protects against infection of HBV. RNA VIRUSES replicate via a DNA copy of their RNA genome. They may be either oncogenic (e.g Rous Sarcoma Virus, human T-cell leukaemia virus 1 & 2) or non oncogenic ( e.g. Human Immunodeficiency Virus, HIV-1 & HIV-2) Retroviral Replication RNA genome serves directly as mRNA Reverse transcriptase uses viral RNA as template for making cDNA strand using tRNA as a primer Rnase H partially digests primer Circularises by RNA-DNA base pairing Dr. MV Hejmadi 0023: DNA: making, breaking & disease DNA synthesised and tRNA primer excised by RnaseH RNA strand displaced and DNA strand linearly recombines with host DNA HCV hepatitis C virus (Flaviridae) HCV infection leads to persistent infection in 50–80% of individuals, a much higher rate than seen for HBV in adults. HCV is increasingly recognized as a cause of HCC, and this will presumably continue as HBV immunization increases. Approximately 10–20% of persistent carriers will develop cirrhosis of the liver, and, of these, 1.5% will go on to develop HCC. At present, no other cancer has been associated with HCV infection HTLV-1 Human T-cell lymphotropic virus types I (Retroviridae) HTLV-I causes adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma, which is endemic in Japan, West and Central Africa Caribbean population of African descent and parts of the south Pacific islands. Infection typically precedes cancer by several decades, and there is a very tight association between the development of cancer and HTLV-I seropositivity. However, the lifetime risk of an HTLV-Iseropositive carrier is estimated to be 2–4%, and most have acquired the infection as children. Genomic organization This is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus, which, like all retroviruses, carries two copies of the genome in the virion. It has a genome of 9 kb and is organized with terminal repeats at either end. The genome codes for viral structural proteins (Gag-core protein, Pol-polymerase and Env-envelope proteins) and the organization of these is similar to that of other retroviruses. In addition, located at the 3′ end of the genome are at least four ORFs coding for regulatory proteins. Replication: As part of their natural replication process, retroviruses integrate proviral DNA sequences into the host cell chromosome, as they code for an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase which will produce a double-stranded complementary DNA molecule with long terminal repeat sequences which allow efficient integration in a sequence-independent manner. This keeps all the coding capacity of the genome intact, and so progeny RNA is produced from the integrated sequences. Activation of cell growth :HTLV-I codes for a number of proteins with sequences near the 3′ end of the genome, often called the pX region. Two of the best-characterized proteins are Tax and Rex. Tax can transactivate the HTLV-I promoter through binding to the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) and the coactivator CBP (CREB-binding protein), mediating the interaction of the latter with the basal transcription machinery. In fact, Tax will activate a number of different cellular promoters through CREB binding and also binding NFκB transcription factors, resulting in the expression of a number of cellular genes, including IL-2, TGF-β, GM-CSF, IL-2α receptor and c-myc. IL-2 is an important growth factor for T cells, the host cells for HTLV-I. Rex is a nuclear protein and regulates the balance between spliced and nonspliced mRNA, thus favouring the transcription and translation of the gag, pol and env genes over the cell regulatory genes expressed through multiply-spliced transcripts. Rex also appears to affect cellular processes, and is thought to act with Tax to increase expression of IL-2α receptor, by an as yet unknown mechanism. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) HIV genome contains 2 copies of +ve strand RNA molecule (9kb long each). Genome encodes 9 genes including 3 structural genes gag (group specific antigen) encodes matrix, capsid, nucleocapsid proteins pol (polymerase) encodes reverse transcriptase, integrase, protease env (envelope) encodes surface & transmembrane protein 6 regulatory genes rev (regulatory virus protein) tat (transactivator) nef (negative regulatory factor) vif, vpr, vpu Dr. MV Hejmadi 0023: DNA: making, breaking & disease The 3 functions of the pol gene include Reverse transcriptase: polymerase activity enabling copying of RNA into dsDNA Integrase: splice HIV DNA permanently into host chromosome Protease: cleaves polyprotein transcripts into packageable forms. Course of HIV infection: The virus is usually transmitted through sexual intercourse, direct exposure to contaminated blood, or transmission from a mother to her fetus or suckling infant. HIV invades certain cells of the immune system--including CD4, or helper T lymphocytes or certain macrophages -replicates inside them and spreads to other cells. HIV infections start with a dramatic drop in CD4 cells (acute phase) within 3-6 weeks, followed by a steady state of viral replication (set point) at about 6 months. CD4 T cell concentrations gradually fall over a period of 8 – 10 years (chronic phase) to below 200 cells / mm3 of blood ( onset of AIDS). COURSE OF HIV INFECTION Group1 – seroconversion-acquisition of virus; flu like symptoms Group 2 – asymptomatic stage (can be 10yr) Group 3 – generalised persistent lymphadenopathy (GPL) lasts ~ 3mth Group 4 – symptomatic infection Antiretroviral or anti HIV therapy All approved anti-HIV drugs attempt to block viral replication within cells by inhibiting either RT or HIV protease. Nucleoside analogues mimic HIV nucleosides preventing DNA strand completion e.g. Zidovudine (AZT), ddI, ddC, Stavudine Non nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTI) e.g Delavirdine and Nevirapine Protease inhibitors block active, catalytic site of HIV protease Multidrug therapy HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) usually consists of triple therapy including 2 nucleoside analogues + 1 protease inhibitor 1 non nucleoside RT inhibitor + 1(2) prot. inhibitor Reading: Chapter 13: Mol & Cell Biol of Cancer by Knowles and Selby Optional Reading Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on Nature Reviews Cancer 4 (10)757-68 Oct 2004 Young LS, Rickinson AB Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection Nature Reviews Immunology 5, 215-229 (2005) Barbara Rehermann & Michelina Nascimbeni Dr. MV Hejmadi