WWI War Preparedness and New Mexico

advertisement

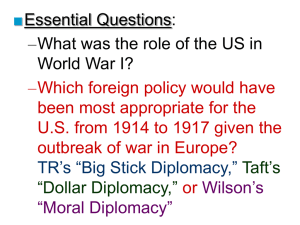

World War I and the Federal Presence in New Mexico War Preparedness and New Mexico Delfino Gonzales, José F. Trujillo, and three friends from Tucumcari joined the Army within days of President Wilson declaring war. They traveled to Albuquerque, enlisted, and reported to El Paso’s Fort Bliss by Wednesday April 11, 1917.Two-and-a-half months later they were on their way to France. On July 4, 1917, the young men from Tucumcari might well have been among the several hundred soldiers, mostly new recruits, who heard the roar of Parisians as American troops paraded five miles through the city to pay tribute at several French military memorials. The soldiers’ presence rallied spirits in the capital city and throughout France—exactly the impact sought by General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Just over a month later, on Wednesday August 15, another contingent of American soldiers marched through London and passed Buckingham Palace, where King George V reviewed them. For the balance of 1917, the five young men from Tucumcari—together with about 160,000 enlisted Regular Army troops and perhaps as many as five-thousand National Guardsmen, including soldiers from New Mexico—trained in France. For the first fifteen months of the war, though, General Pershing largely presided over an army-in-drill. His plans called for combat-readiness to be developed in two stages: six months’ stateside general military training followed and another three months in France to acquire proficiency in defensive tactics and offensive maneuvers. Combat readiness took time, something well-known to the allies and Germans alike. France and Germany had large, well-trained standing armies of nearly a million men each in 1914; Great Britain did not—and neither did the United States in 1917. All militaries exist to defend a country when attacked and to mount a combat offensive when needed. The United States’ military proved unprepared to do either in 1917. No one should have been surprised by the American military’s lack of readiness. In 1912, the Secretary of War described the Army’s degree of combat worthiness as “zero.” The military’s lack of preparedness roiled national politics in 1915 and 1916, and New Mexico’s two senators and one congressman found themselves on opposite sides. Senators Albert B. Fall and Thomas B. Catron, along with most Republicans and some Democrats, supported accelerating militarization, calling for a doubling in the number of regular army troops to at least 250,000 (from just over 125,000). New Mexico’s two senators disagreed only on the ends for such a build-up: Fall, even as late as mid-February 1916, thought only in terms of Mexico in advocating war preparedness. Senator Catron, in a July 25, 1915 letter to the New York Times advocated a significant increase in the army and navy as well as having the federal government be more active in creating “a well-disciplined reserve, with which we could fill up the regiments and companies of the regular army, and in the shortest possible time.” To his credit, though, Fall was forward thinking on one key issue. As he told the New York Times early in 1916, “The Government, too, should establish its own munitions and guns plants, sufficient to meet all requirements.” Not until late in the war did the federal government decisively address the critical need for munitions, and then it essentially adopted Senator Fall’s proposal. Civilians were tapped to supply federal workers for government run armament factories, and in September 1918, more than 300 New Mexico men from the counties of Santa Fe, San Miguel, Colfax, Chavez, and Bernalillo departed for Tennessee—at the government’s expense— to work at a federally run munitions manufacturing plant. Democratic Representative Harvey B. Fergusson aligned with the Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, as a forceful voice for pacifism within Wilson’s administration afer leaving congress in March 1915. He immediately became the private secretary to Secretary Bryan, and during the remaining months of his life he and Bryan worked tirelessly to curb militarization. For his part, President Wilson presided over a nation divided three ways in the runup to America’s entry into World War I. Naturally pro-German sentiment abounded in many immigrants from that country and their first-generation descendents, and these numbered over ten million. Pro-English sentiment ran high as well. But a sizable number of Americans genuinely sought neutrality or were pro-peace. Against this divided opinion, President Wilson campaigned for re-election in 1916 as the candidate who “kept us out of war” in Europe. President Wilson carried New Mexico by a margin of 2,375 votes out of 66,787 cast, or 3.56 percent. Nationwide the president won re-election with a margin of victory of 3.12 percent (578,140 votes out of 18,536,585 ballots cast). In the Electoral College, Wilson garnered 277 votes and his Republican opponent, Charles Evans Hughes, received 254. Two minor party candidates, representing the Socialist and Prohibition parties, received no electoral college support but did draw 811,826 popular votes. Wilson’s re-election in the fall of 1916 has to be understood as reflecting the public’s narrow preference to avoid fighting abroad. New Mexico’s politicians in Washington typified divisions within the nation over preparedness, and the senators’ attitudes revealed impatience with congressional and presidential hesitancy. At bottom, as one historian has noted, In the United States, a traditionally antimilitaristic country, the armed forces [in 1917] had long been the stepchild of the nation. Unlike all the European countries, the United States imposed no obligatory military service. The U.S. Congress was reluctant to appropriate large funds for the military. General John J. Pershing first encountered problems caused by Congress’s dithering over preparedness during his duty as commanding general of Fort Bliss at El Paso beginning in the spring of 1914. But he acutely experienced them from March 1916 through February 1917 with the call up of Nation Guard units following the raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Still, Pershing forged an effective fighting force in 1916-1917. When he departed Columbus, Pershing knew and trusted the capabilities of the 5,000 Regular Army soldiers from Fort Bliss he had led in Mexico. These troops, augmented by recent enlistments such as the young men from Tucumcari, constituted his “army” sent to France in June 1917. © 2008 by David V. Holtby Supplying the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) ran from the mundane (paragraph 1) to the critical (paragraph 4). The 41st Division, which included New Mexicans, is informed their draft animals, transported on two ships, departed on December 9, 1917. (paragraph 7 final sentence). NARA II, Record Group 120, American Expeditionary Forces, Division Records, 41st Division, Box 1. This order from mid-October 1918 on the proper fitting of shoes is illustrative of how long it took the army to fully organize and plan for its troops’ needs. NARA I, Record Group 393, Camp Kearny, Box 5. Redacted and transcribed from the second paragraph of a June 1917 account “Mobilizing the Forces of America for War,” Current Opinion, June 1917, Vol. LXII, No. 6. p. 1