ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

6. ‘IF THE PUBLIC KNEW BETTER, THEY WOULD ACT

BETTER’: THE PERVASIVE POWER OF THE MYTH OF

THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

INTRODUCTION

Museums, aquariums, science centres, zoos and other informal science institutions

(ISIs) are increasingly committed to engaging the public in issues connected to

environmental conservation and sustainability. Although ISIs around the world

may hold different views about what information should be shared with the public,

they appear to share the belief that ‘if the public knew better, they would act

better’. They operate within a common authoritative discourse about the power of

education to transmit information from those who are knowledgeable to those who

are not (Kelsey, 2001).

In this chapter, we explore the implications of this particular discourse on

environmental learning, participation and agency within informal science

institutions. More specifically, we examine a case study of conversational learning

between guests (visitors) and volunteer guides in the galleries of a major US

aquarium. This is a particularly timely topic, as the interaction between ISIs and

their publics has undergone significant change in recent years. Throughout the

1980s and 1990s, environmental public participation programs operated in a type

of ‘decide-announce-defend’ mode based on a ‘one way’ transfer of information

from experts to the public (Davies et al., in press). Such programs echoed a deficit

model of Public Understanding of Science (PUS) rhetoric, with its tacit assumption

of public ignorance (Lehr et al., 2007).

Today, a new emphasis on ‘co-determined’ decisions and ‘two-way’ exchanges

between experts and the public of both information and values has emerged. As

Lehr et al. (2007) put it, ‘the deficit model has—in theory, at least—been firmly

rejected in response to a series of crises in the public trust of science and the

government in the 1990s (for example, the BSE and genetically modified foods

controversies), and a ‘new mood for dialogue’ between scientists, policy-makers,

and various publics has emerged as its replacement’ (House of Lords Select

Committee on Science and Technology, 2000, p. 44).

A major response from ISIs to this shift toward more authentic public

participation has been the creation of ‘dialogue events’ (Lehr et al., 2007). Lehr et

al. define these as face-to-face, adult-focused forums that bring scientific and

technical experts, social scientists, and policy-makers into discussion with

A.N. Other, B.N. Other (eds.), Title of Book, 00–00.

© 2005 Sense Publishers. All rights reserved.

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

members of the public about contemporary scientific and socio-scientific issues. A

number of ISIs now host Café Scientifiques where members of the public are

invited to informal gatherings to discuss current issues of science, environment

and/or technology (McCallie et al., 2007). The Dana Centre, which opened in 2003

at the London Science Museum, for example, is a purpose-built venue which

describes itself as ‘a place for adults to take part in exciting, informative and

innovative debates about contemporary science, technology and culture’ (Dana

Centre, 2008).

Rather than focusing on special ‘dialogue events’, which occur in specialized

areas and/or at scheduled times, this paper deals with another highly

complementary locus for environmental learning, participation and agency in ISIs,

that is, the interactions between volunteer guides and visitors in the public galleries

of ISIs, and the potential they hold for learning through conversations.

THE VALUE OF LEARNING THROUGH CONVERSATIONS

A growing body of research in out-of-school contexts recognizes that people learn

in museums through conversations (Leinhardt, Crowley, & Knutson 2002). Indeed,

much attention has been paid to research on conversations between visitors at

recent annual conferences of the Visitor Studies Association, the Association of

Science-Technology Centers, the National Association for Research in Science

Teaching (NARST) and the American Educational Research Association (AERA)

(see for example the AERA 2002 symposium entitled Learning conversations for

all: Explanation, reflective reasoning, thematic content and significant events).

There is also a well-articulated awareness within the research literature of the

importance of conversation to enhancing and changing knowledge, attitudes and

values (Baker, Jensen, & Kolb, 2002; Jickling, 2004; Laurillard, 1993; Lave &

Wenger, 1991).

In terms of environmental learning, Rennie (2003) finds that conversation

promotes engagement in environmental awareness or action projects. A number of

authors highlight the role of conversation in increasing public participation in

politics and in real-world issues (Bobbio, 1987; Bohman & Rehg, 1997; Chambers,

1996; Cohen, 1989; Elster, 1998; Fishkin & Luskin, 2005; Gutmann & Habermas,

1996; Keane, 1991; Public Conversations Project, 2008; Zeldin, 1998).

Much of the literature on the role of language in learning fits with in a

Vygotskian/sociocultural paradigm (as explicated by Wertsch, 1991) in which it is

the social plane that is so critical to development, through interaction, primarily

through talking. Indeed, a growing body of literature emerging from research in

schools points to the key role of ‘exploratory talk’ (Barnes, 1976), discussion,

dialogic teaching, dialogic inquiry, collaborative reasoning (Chinn and Anderson,

1998) and argumentation, as playing critical roles in developing conceptual

understanding and changes in mood and emotion (Rojas-Drummond & Mercer,

2003; von Aufschnaiter et al., 2008). At the heart of the debate is language which,

as Halliday points out, ‘has the power to shape our consciousness; and it does so

for each human child, by providing the theory that he or she uses to interpret and

manipulate their environment’ (1993, p. 107).

THE POWER OF THE MYTH OF THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

Mercer and Littleton (2007) characterise exploratory talk (Barnes, 1976) as being:

dialogue which involves partners in a purposeful, critical and constructive

engagement with each other’s ideas. Statements and suggestions are offered

for joint consideration. These may be challenged and counter-challenged, but

challenges are justified and alternative hypotheses are offered. Partners all

actively participate, and opinions are sought and considered before decisions

are jointly made. ‘Exploratory talk’ has some similarities with the notions of

‘accountable talk’ (Resnick, 1999) and ‘collaborative reasoning’ (Chinn and

Anderson, 1998). (Mercer, 2008, p. 357)

Now, many of these ideas may not be supported by rigorous empirical research but

they act as powerful lenses through which to see how discussion and dialogue

impact on learning in its broadest sense. In terms of dialogue, Mercer (2008) notes

that:

It is our natural habit to express our ideas in dialogue, to test our views

against those of others, and to attempt to persuade other people to share the

conceptual understandings that we believe are the best. It is of course also

normal that we resist changing our minds, if the views we hold are bound up

with aspects of our social identities. But, nevertheless, most of us proceed as

if we believe that one of the most important ways of changing someone’s

mind is to talk with them. (p. 355)

Many environmental issues, as they impact on the interface between science and

society, are controversial. To help make sense of these controversies, we would

argue that the public would benefit from a deeper understanding of the ways in

which scientific understanding develops. One of the ways in which young people

may come to understand the nature and development of science is by engaging in

the processes of argumentation, that is, building knowledge through purposeful

weighing of evidence and analysis of warrants for ‘truth’. We know something

about how argumentation, a foundation of the ways in which science works can be

taught to young people. Much of the work of Osborne and colleagues points to the

fact that teachers can be taught to develop higher order argumentation given

enough time (see, for example, Simon, Erduran, & Osborne, 2006).

Rather than teaching the ‘neutral’ skills of argumentation or dialogic talk, ISI

programs, such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch initiative,

endeavor to use these formats to engage visitors and persuade them to change their

actions. But human decision-making is hard to affect, as Eiser and van der Pligt

(1988) argue:

[evidence suggests] that the conscious thought preceding a decision may be

of a relatively simple nature, given the difficulty of processing complex

information. People seem to rely on simple heuristics for making probability

judgements and hardly seem to think about more complex combinations of

probabilities and values or utilities involved in a decision […] In other words,

people’s decision processes seem relatively inarticulated and are hardly

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

compatible with the sort of rigorous, systematic thinking required by

normative decision models. (p. 181)

So given these limitations, how can ISIs play an active role in promoting

conservation using conversations? The potential to do so is very high: every year,

for example, more than 143 million people visit zoos and aquariums (Falk et al.,

2007). Furthermore, there is evidence that visitors seek opportunities to converse

about issues of societal importance during their visits. Cameron (2003) found that

95% of people surveyed in an Australian sample wanted museums to provide more

opportunities for visitors to have their say about topics; to converse; to exercise

their democratic right to be heard in a publicly funded institution. Fortunately,

volunteer educators (guides or docents) already exist as a well-established part of

the operation of ISIs in many countries and rather than static exhibits, these

volunteers represent a tremendous opportunity to engage the public in personally

relevant conversations about current environmental issues.

THE PREVALENCE OF MINI-SCRIPTS

Despite the potential value of conversational learning, dialogue and exploratory

talk in theory, a multi-year study of a major USA aquarium reveals that such

conversations are rarely observed in practice. Instead, guides typically default to a

one-way transfer of information to visitors in the form of ‘mini-scripts’ (Kelsey,

2004). Kelsey defines mini-scripts as predetermined statements which guides tend

to pair with specific animals or props. Although not officially scripted, these

statements are repeated so frequently that they take on the appearance of standard

scripts, and are sometimes shared across shifts and individuals. At the touch pools,

for example, at least one tenth of the aquarium’s 500 volunteer guides say ‘sea

cucumbers and chitons are the vacuum cleaners of the sea’ and ‘sea urchins feel

like a hairbrush’ even though no formal script actually exists. Rather than engage

in conversations, guides tend to create a longer engagement sequences by moving

from one prop to another, stringing together mini-scripts for each specimen or

piece of apparatus.

Though no other study of mini-scripts has yet been conducted, their presence

appears to be well-recognized by professional educators working in ISIs. Each time

they are mentioned at presentations at AERA, NARST and the North American

Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE), professional colleagues have

been quick to acknowledge their existence at their own host institutions. Sanders,

for example, describes the tendency for Explainers at the Natural History Museum

in London to favor particular entry points, or “opening gambits” in their

interactions with students (personal communication).

In 2006, an opportunity to explore the tenacity of mini-scripts presented itself at

the same aquarium where they were first identified. The aquarium had just

established a new ‘Take Action’ temporary exhibit on marine protected areas

(MPAs) to coincide with a major initiative to grant further conservation protection

to MPAs along the California coast. The exhibit provided information on the issues

and names and addresses of elected officials. It invited guests to become more

THE POWER OF THE MYTH OF THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

engaged and explore issues in more detail by inviting them to sign up for an email

listserve operated by the aquarium.

The exhibit was located in close proximity (approximately 15 feet) from a guide

station called the ‘Ocean Advocacy Station’. The station takes the form of a large

cart equipped with props such as cans of seafood, a computer screen and ‘Seafood

Watch’ cards. Guides use the station as a base from which to interact with visitors

or “Guests” as they are referred to at the aquarium. Each guide shift was given

specific training and enrichment sessions about the issue of MPAs and asked to

engage guests in conversations about the issue. It is important to note that these

training sessions deliberately used a conversation-based instruction style that

invited guides to share their own thoughts about and experiences with MPAs in a

facilitated group format. The MPA campaign was timely, local, clearly endorsed

by the aquarium and supported by the new exhibit. It was hypothesized that guides

would readily engage guests in conversations about MPAs as a result of:

– overt institutional support;

– specific guide training; and,

– specific gallery location (guide cart in close proximity to ‘Take Action’ exhibit)

However, during 15 half-hour observation sessions by one of the authors (EK),

guides did not engage guests in conversations about MPAs even when presented

with the opportunity. Instead, they stuck to their mini-scripts associated with the

Ocean Advocacy Station.

Further analysis of the guides’ actions revealed the following findings:

1) Guides adhered to mini-scripts that were prop-driven. Rather than discuss

MPAs, the guides talked about Seafood Watch using the cards, video clips and

cans of seafood on their cart.

2) Guides were ‘glued’ to their cart, even in circumstances where there were no

guests at the cart and there were guests at the Exhibit. Only one guide in the 15

observation sessions left the guide cart to engage guests at the ‘Take Action’

exhibit.

3) The ‘Mini-scripts’ used at the carts lacked context and created confusion. Miniscripts at the guide cart existed as a series of simplified sentences that were strung

together and repeated frequently. The problem here is that many important

concepts that served to make the complexity of the ideas understandable were lost

in the repetition. For example, some guides were so eager to advocate the

consumption of wild caught salmon that when a guest picked up a can of tuna and

asked which kind of tuna is dolphin safe, the guide responded with a mini-script

about the benefits of wild caught salmon.

4) The ‘Mini-scripts’ used were not personalized. In responding to visitors, the

guides tended to draw on a number of favourite phrases and linked them together

in response to guest questions or comments, creating the impression that a

conversation was happening. However, the sentences themselves remained the

same no matter who the guide was speaking with or what the guest

asked/answered. For example, one guide asked every guest who stopped at the

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

station if they had seen the movie A Perfect Storm. None of the guests answered in

the affirmative, yet each time, the guide proceeded to explain how well the movie

depicted a certain kind of fishing practice.

5) The ‘Mini-scripts’ used were not age appropriate. In the observation sessions,

guides were very friendly to children but did not change their ‘mini-scripts’ when

children were present. Thus, in a number of encounters preschool and early

elementary school aged children were asked if they liked to eat tuna and then told

about the dangers of high mercury levels or the entrapment of dolphins and their

babies during tuna purse seining fishing. The lack of age sensitivity on the part of

the guides is worrying not least because there is mounting evidence from

researchers such as Sobel (1996, 2008) of the dangers of presenting children with

examples of environmental problems before they are emotionally and

developmentally (around age eight years old) equipped to deal with them..

Subsequent discussions with a focus group of eight guides revealed that guides

had a different perception of their interactions with visitors in that when asked

specifically how they transferred the experiences of their MPA training to their

conversations with guests, most guides answered decisively that this readily

occurred. As one guide expressed: ‘Many, probably most, (guides) are highly

educated here so they are able to integrate that information into the other stuff that

they know and to present it at different locations.’ Yet, from observations, the

transfer did not happen. Guides did not share information they learned at the MPA

enrichments with guests at the guide cart during any of the observation sessions.

Instead, they adhered to the familiar mini-scripts associated with the Seafood

Watch program.

SO WHY ARE MINI-SCRIPTS TO PERVASIVE?

The evidence above demonstrates the pervasiveness of mini-scripts in these

volunteers’ practice. It appears that the guides’ own experiences of schooling and,

perhaps, the traditional lecture approach become so ingrained that they are hard to

shake despite a training format that modelled conversational learning and an

explicit request to engage the guests in conversation. It suggests that this

transmissionist model on learning, teaching, and communicating is the default,

despite interest in the field (both researcher and practitioners) and the aquarium

leadership to act and believe otherwise.

We see an answer, partly, in the work of Mortimer and Scott who have

researched the difficulties faced by schoolteachers trying to move from what they

call authoritative teaching to more dialogic teaching. Mortimer and Scott have

identified ‘Four Classes of the Communicative Approach’ (Scott, Mortimer, &

Aguiar, 2006):

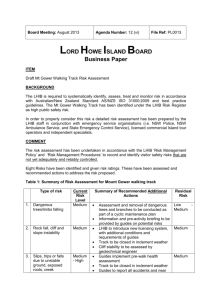

a. Interactive/dialogic: Teacher and students consider a range of ideas. If the level

of interanimation is high, they pose genuine questions as they explore and work on

different points of view. If the level of interanimation is low, the different ideas are

simply made available.

b. Noninteractive/dialogic: Teacher revisits and summarizes different points of

view, either simply listing them (low interanimation) or exploring similarities and

differences (high interanimation).

THE POWER OF THE MYTH OF THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

c. Interactive/authoritative: Teacher focuses on one specific point of view and

leads students through a question and answer routine with the aim of establishing

and consolidating that point of view.

d. Noninteractive/authoritative: Teacher presents a specific point of view.

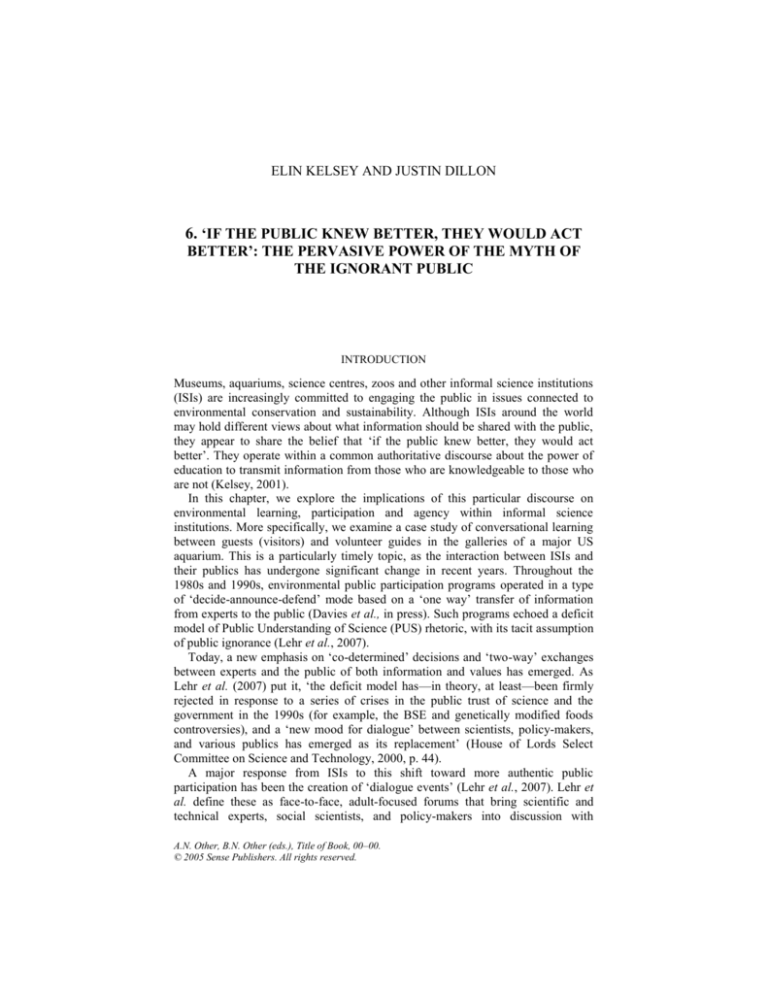

Table 1 indicates the four classes of communicative approach model schematically.

INTERACTIVE NON-INTERACTIVE

AUTHORITATIVE

DIALOGIC

interactive/

authoritative

(e.g. teacher-led discussion)

non-interactive/

authoritative

(e.g. teacher lecture)

interactive/

dialogic

(e.g. teacher/student

collaboration)

non-interactive/

dialogic

(teacher summarises students’

views)

Figure 1: Four classes of communicative approach

(Adapted from Mortimer & Scott, 2003, p.35)

What the model points to is a tension between the talk associated with

authoritative science knowledge and the kind of knowledge built by students

engaged in dialogic activity. While Mortimer and Scott suggest a need to have a

balance of approaches, they argue that interactive dialogic is preferable for

exploring ideas and facilitating their engagement. Wells (1997) argues that dialogic

discourse does not necessarily mean an equal discourse. From this perspective the

guides would be seen to have a responsibility to shape the exchange. Yet the

prevalence of mini-scripts suggests that the transition from authoritative

communication to dialogic communication fails to occur.

Furthermore, McCallie (2008, personal communication) makes a distinction

between teaching in contexts in which there is a preordained set of information to

be learned – ‘learning for mastery’ – as opposed to a more open learning agenda in

which what is to be learned is not yet known or codified. In other words, what is to

be learned is yet to be figured out. The question of whether or not to establish

MPAs, for instance, is a socio-scientific issue that fits in the latter category. Guides

could engage in discussions about what could be done, for example, ‘The

Aquarium thinks this, what do you think?’

Yet we believe that these teaching and learning considerations are only part of

the answer. The idea of a common discourse that prevents ISIs from realizing their

stated aim with respect to public engagement is supported by the notion of

‘structure’ as described by Sewell (1992) and Giddens (1991). According to Sewell

(1992, p. 3) structure is an elusive and difficult to describe a notion that reflects

‘something very important about social relations: the tendency of patterns of

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

relations to be reproduced, even when actors engaging in the relations are unaware

of the patterns or do not desire their reproduction.’

The degree of guide agency meanwhile, that is the capacity of individuals to act

independently of the structures imposed by social systems, remains a question of

debate. In his theory of structuration, for example, Giddens (1991) argues that it is

a mistake to pose social systems and individual agency as separate from one

another because neither exists except in relation to the other. In this sense, there is

what Giddens calls a duality of structure, which is to say the structure of a system

provides individual actors with what they need in order to produce that very

structure as a result. Structures, says Giddens, are both the medium and the

outcome of the practices that constitute social systems. Structures shape people’s

practices, just as people’s practices constitute and reproduce structures.

One of the hallmarks of structures, according to Sewell (1992), is that it is often

difficult for one engaged in a pattern to be aware of it. Thus, it is possible that ISIs

operating within a common structure—in this case, a common discourse about

scientific knowledge, the public and education—will be unaware of it even while

their actions serve to sustain and reproduce it.

The power of discourses to shape public life, whether or not individuals engaged

within these discourses are aware of them, forms the basis of Foucault’s (1988)

work on the connections between language, knowledge, power and social control.

Foucault argues that language and knowledge form a basis for power in their role

in the social construction of reality. The modern mode of domination, he claims, is

based on a combination of scientific disciplines and professional and

administrative practices which penetrate each and every socialised subject of

society. How we talk and think about the world shapes how we behave and the

kind of world we help to create. Discourses are powerful because they both define

and limit the ways in which we conceptualise reality (Gee, 1999).

Blades (1997) provides an example of Foucault’s theory in action in a formal

education setting through his case study of curriculum change in secondary school

science. According to Blades (1997, pp. 2-3):

attempts to change secondary school science education curricula are defined

and thus limited by the positivistic, technical-rational assumptions of the

discourse of modernity. So en-framed, curriculum change seems destined to

technicality, to a view of change as a problem to be solved once all the

factors are elucidated; a search for the correct method and generalisable

technique.

SO, WHERE NEXT?

The prevalence of mini-scripts indicates a worrisome disconnect between the stated

intention of ISIs to serve as sites for public engagement and the realities of the

interactions between guides and guests. The use of mini-scripts has the

unintentional effect of treating the visiting public as if they are ignorant and/or as if

they don’t know what questions to ask or what information they need. This

disconnect is further mirrored in volunteer guide training programs and

enrichments which are typically structured as information dissemination sessions

THE POWER OF THE MYTH OF THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

where guides are told by an expert staff member (often in a friendly though

authoritative, non-interactive manner) how they should interact and engage in

dialogue with visitors. Adding a few conversational learning sessions is not

sufficient to help guides learn how to transition between authoritative information

giver and dialogic discourse promoter.

A major issue with dialogue is that it is not ‘secure’ or ‘consistent.’ It is far

more challenging than following mini-scripts. In order to engage in argument (or

dialogue in general) one must have a much stronger command of the information in

order to think and be flexible with it. It is the difference between ‘knowing

something’ ‘and being ‘literate’ in the sense of being able to apply information and

skills in a variety of contexts.

Failure to create and model a conversational learning environment for guides

serves to reinforce the status quo and to undermine the guides’ participation and

agency in engaging guests in conversational learning in the public galleries. Yet

changing the structure of guide training sessions is not an easy task. Training

sessions are a mainstay of most volunteer guide programs and both staff and

volunteers have strong, well-established expectations about how training should be

conducted. Volunteers at the aquarium described in this paper, for example, speak

in proud terms about having survived ‘training boot camp’ wherein they mastered

scientific names of marine invertebrates and challenging concepts of ocean

geomorphology.

For many ISIs, including the one mentioned in this paper, the corps of

volunteers is even more stable than its staff. These long-term, experienced guides

serve an important ‘gate-keeping’ role in inspiring and maintaining a high level of

professionalism. Though keenly committed to remaining ‘cutting edge’, a number

of these individuals are of the opinion that the existing system of guide training and

guest/guide encounters is working well and needs little change. The fact that

experienced guides mentor new guides at the stations further perpetuates the

traditional discourse of guide as information giver rather than dialogist.

Furthermore, many volunteers are seniors who attended school at a time when

the teacher was the unquestioned source of expertise and authority. Beginning

attempts to create training sessions that challenge this norm by facilitating learning

through conversations have been met with enthusiasm by some volunteers but notunexpectedly, with confusion and scepticism from others.

Nevertheless, this aquarium and a growing number of ISIs (see for example

Osborne and Rodari’s work regarding training programs for museum educators

across Europe) are interested in improving and developing their training programs,

especially with regards to learning literature.

Perhaps the greater barrier to progress is the institutional identity of ISIs. ISIs

have a distinguished history as a ‘trusted source of information’ with respect to

science (Astor-Jack et al., 2006). This identity as a purveyor of science authority

and expertise further reinforces a transmission-based learning culture in both guide

training programs, and the ways in which guides interact with the public in exhibit

galleries. Yet as the past decades of conservation initiatives attest, the issues are

rarely straightforward. Nor are they exclusively confined to problems issues are

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

rarely straightforward. Nor are they exclusively confined to problems answered by

science. As Johnson et al. (2001) note, conservation issues are defined as much by

socio-cultural values and political and economic factors as by the biophysical

dimension. Indeed, the complexity of conservation issues is evidenced by the

multiple roles that ISIs are increasingly adopting (information source, habitat

protector, political advocate, role model, etc.) with respect to conservation action.

The ideas put forward in this paper recognize the importance of learning models

that openly encourage and value multiple ideas and perspectives (Layton et al.

1993; Larochelle, Bednarz, & Garrison, 1998). Such models challenge the belief

that facts speak for themselves and, instead, emphasize the active role of the

learner and the contextual nature of learning. Clarifying messages and transmitting

ISIs positions on key conservation issues is one important institutional role. Yet,

the goal of engaging the public in conservation demands that ISIs continue to

expand their identity as a scientific authority to more fully embrace their identities

as a forum and facilitator of a conversational learning culture.

REFERENCES

Astor-Jack, T., Balcerzak, P., & McCallie, E. (2006). Professional development and the historical

tradition of informal science institutions: Views of four providers. Canadian Journal of Science,

Mathematics, & Technology Education, 6(1), 67-81.

Baker, A., Jensen, P., & Kolb, D. (2002). Conversational learning: An approach to knowledge creation.

Westport, Connecticut: Quorum.

Barnes, D. (1976). From communication to curriculum. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Blades, D.W. (1997). Procedures of power and curriculum change: Foucault and the quest for

possibilities in science education. New York: Peter Lang.

Bobbio, N. (1987). The future of democracy: A defence of the rules of the game. Cambridge: Polity.

Bohman, J., & Rehg, W. (Eds.). (1997). Deliberative democracy: Essays on reason and politics.

Boston, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Cameron, F. (2003). Transcending fear - engaging emotions and opinion – a case for museums in the

21st century. Open Museum Journal. i, 1-46. Retrieved on December 24, 2008 from

http://archive.amol.org.au/omj/volume6/cameron.pdf.

Chambers, S. (1996). Reasonable democracy: Jurgen Habermas and the politics of discourse. Ithaca,

New York: Cornell University Press.

Chinn, C.A., & Anderson, R.C. (1998). The structure of discussions that promote reasoning. Teachers

College Record, 100, 315-368.

Cohen, J. (1989). Deliberation and democratic legitimacy. In A. Hamlin, & P. Pettit (Eds.) The good

polity. New York: Blackwell.

Dana Centre/Science Museum. (2008). Dana Centre: About us. Retrieved on December 24, 2008 from

http://www.danacentre.org.uk/aboutus.

Davies, S., McCallie, E., Simonsson, E., Lehr, J., & Duensing, S. (in press). Discussing dialogue:

Perspectives on the value of science dialogue events that do not inform policy. Public

Understanding of Science.

Eiser, J. R. and van der Pligt, J. (1988). Attitudes and decisions. Routledge: London.

Elster, J. (Ed.). (1998). Deliberative democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Falk, J.H., Reinhard, E.M., Vernon, C.L., Bronnenkant, K., Deans, N.L., & Heimlich, J.E. (2007). Why

zoos and aquariums matter: Assessing the impact of a visit. Silver Spring, Maryland: Association of

Zoos and Aquariums.

Fishkin, J.S., & Luskin, R.C. (2005). Experimenting with a democratic ideal: Deliberative polling and

public opinion. Acta Politica, 40(3), 284-298.

THE POWER OF THE MYTH OF THE IGNORANT PUBLIC

Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, philosophy, and culture: Interviews and other writings, 1977-1984, edited

by M. Morris and P. Patton. New York: Routledge.

Gee, J. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. New York: Routledge

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

Gutmann, A., & Thompson, D. (1996). Democracy and disagreement. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms. Boston, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1988). On the language of physical science. In M. Ghadessy (Ed.) Registers of

written English: Situational factors and linguistic features. London: Frances Pinter.

House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology (2000). Third Report: Science and

Society. Retrieved on December 24, 2008 from http://www.parliament.the-stationeryoffice.co.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ldsctech/38/3801.htm.

Jickling, B. (2004). Making ethics an everyday activity: how can we reduce the barriers? Canadian

Journal of Environmental Education, 9, 11-30.

Keane, J. (1991). The media and democracy. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Kelsey, E. (2001). Reconfiguring public involvement: Conceptions of ‘education’ and ‘the public’ in

international environmental agreements. Unpublished PhD thesis, King’s College London, UK.

Kelsey, E. (2004). From science learning to conversations about conservation: A study of guide

training at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National

Association for Research in Science Teaching, Vancouver, British Columbia, April 1-3, 2004.

Larochelle, M., Bednarz, N., & Garrison, J. (Eds.). (1998). Constructivism and education. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Laurillard, D. (1993). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of educational

technology. London: Routledge

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Layton, D., Jenkins, E., Macgill, S., & Davey, A. (1993). Inarticulate science? Perspectives on the

Public Understanding of Science and some implications for science education. Nafferton: Studies in

Education Ltd.

Lehr, J.L., McCallie, E., Davies, S., Caron, B.R., Gammon, B., & Duensing, S. (2007). The value of

“dialogue events” as sites of learning: An exploration of research and evaluation frameworks.

International Journal of Science Education. 29(12), 1467-1487.

Leinhardt, G., Crowley, K. and Knutson, K. (2002). Learning conversations in museums. Mahwah, New

Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McCallie, E., Kollmann, E. K., Simonsson, E., Chin, E., & Dillon, J. (2007). Visitors and engagement:

Findings from research and evaluation studies of discussion forums on controversial issues. Paper

presented at the 20th Annual Visitor Studies Association Conference. Columbus, Ohio: Visitor

Studies Association. Abstract available at: http://www.informalscience.org/research/show/3574.

Mercer, N. (2008). Changing our minds: a commentary on ‘Conceptual change: a discussion of

theoretical, methodological and practical challenges for science education’ by D.F. Treagust and R.

Duit, Cultural Studies in Science Education, 3(2), 351-362.

Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A

sociocultural approach. London: Routledge.

Mortimer, E. F., & Scott, P. H. (2003). Meaning making in secondary science classrooms. Maidenhead,

UK: Open University Press.

Public Conversations Project (2008). Public Conversations Project. Retrieved on December 24, 2008

from http://www.publicconversations.org/pcp/pcp.html.

Rennie, L. (2003). The Australian Science Teachers Association science awareness raising model: an

evaluation report. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training. Australian

Government.

Resnick, L.B. (1999). Making America smarter. Education Week. 18(40), 38-40.

ELIN KELSEY AND JUSTIN DILLON

Rojas-Drummond, S., & Mercer, N. (2003). Scaffolding the development of effective collaboration and

learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 39, 99-111.

Scott, P.H., Mortimer, E.F., & Aguiar, O.G. (2006). The tension between authoritative and dialogic

discourse: A fundamental characteristic of meaning making interactions in high school science

lessons. Science Education. 90(4), 605-631

Sewell, W.F. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. American Journal of

Sociology, 98(1), 1-29.

Simon, S., Erduran, S. and Osborne, J. (2006). Learning to teach argumentation: research and

development in the science classroom. International Journal of Science Education. 28(2&3), 235260.

Sobel, D. (1996). Beyond ecophobia: Reclaiming the heart in nature education. Great Barrington,

Massachusetts: Orion Society.

Sobel, D. (2008). Childhood and nature: Design principles for educators. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse

Publishers.

von Aufschnaiter, C., Erduran, S., Osborne, J., & Simon, S. (2008). Arguing to learn and learning to

argue: Case studies of how students' argumentation relates to their scientific knowledge. Journal of

Research in Science Teaching. 45(1), 101-131.

Wells, G. (2008). Learning to use scientific concepts, Cultural Studies in Science Education. 3(2), 329350.

Wertsch, J.V. (1991). A sociocultural approach to socially shared cognition. In L.B. Resnick, J.M.

Levine, & S.D. Teasley (Eds.) Perspectives on socially shared cognition. Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Zeldin, T. (1998). Conversation: How talk can change your life. London: Harvill Press.

Elin Kelsey

Royal Roads University

Justin Dillon

King’s College London