US farm policy is a controversial and emotional issue in American

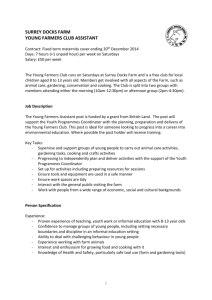

advertisement

Subsidy reform in the US context: deviating from decoupling Ann Tutwiler In 1983, a US senator and several aides were discussing ideas to reform US farm policy. At the time, high government support prices were interfering with the market and the government was accumulating stocks. The aides proposed deeply cutting support prices and substituting direct payments that were “decoupled” from prices and production. Around the same time agricultural economists began to recognize that domestic agricultural policies had significant impacts on world markets. They started to distinguish between different types of agricultural policies and to measure the impact that these policies had on world markets. Payments that were decoupled from prices and production had smaller negative effects on world markets and on third countries. These ideas were taken up by Uruguay Round negotiators when they classified different agricultural policies into Amber, Blue and Green Boxes. Negotiators were explicitly recognizing the work of these policy makers and economists: that some policies (which came to be known as Amber and Blue Box) had a bigger impact on global trade than others, and that these policies should rightly be disciplined by the World Trade Organization. They also recognized that some policies (known now as Green Box measures) had less impact on world trade and should be exempt from WTO disciplines. They were implicitly hoping to drive US and EU policies away from Amber and Blue Box subsidies, into Green Box subsidies. At one level, Green Box measures in the United States have been increasing and will continue to increase as a share of overall budget assistance to the US food and agricultural sector. As the table below illustrates, the main elements of the US Green Box subsidies are food assistance programs for low income school children and other Americans, environment and land conservation programs, structural adjustment, general services (research and food safety). Direct payments to farmers, which receive the bulk of attention in trade negotiations, account for a small percentage of total US Green Box measures. In 2005, 70 per cent of US Green Box measures (or $50.7 billion) fell under food assistance programs (Figure 1). Under the new farm bill, the assistance provided to low income families and to environmental programs has been increased further. 1 Figure 1: US Green Box Payments, Notified (1995-2001) and Projected (2002-2013)1 Environmental payments Investment aids Resource Retirement Disaster relief Decoupled Income support Domestic Food Aid 11 13 20 20 07 09 20 20 03 05 20 20 99 01 20 19 97 General Services 19 19 95 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 But, in terms of policy structure and payments to farmers, US farm legislation is continuing to move away from decoupled income support to re-coupled income safety nets — in WTO speak, away from Green Box and toward Amber Box, or box shifting in reverse. Even though the concept of decoupling did not appear until 1985, the economic philosophy of “decoupling” began to play a role in US farm policy as early as 1981, culminating with the 1996 Freedom to Farm legislation. In 1998, Congress retreated from decoupling with emergency Agricultural Market Transition Account payments. In 2002, Congress made these transition payments permanent and instituted counter-cyclical payments that increased as market prices fell. Direct, decoupled payments remained an important part of US farm policy. But after nearly twenty years of slow, steady, incremental moves toward decoupling, it appears that the move toward decoupling may be stalled or thrown into reverse in the 2008 farm bill. To appreciate the dynamics of the 2008 farm bill debate, it is useful to delve into history a bit. The farm programs that emerged out of the Great Depression were relatively modest until the 1981 Farm Bill. That bill contained all the elements of the 1970s farm programs but a perfect storm of recordbreaking harvests, a global recession, interest rates in excess of 20 percent and a credit crunch combined to trounce land values and create real problems in rural America. Costs under the 1981 farm bill soared. Congress responded to the rural crisis with the 1985 Farm Bill, a very expensive farm bill that retained many elements of Depression era policies, but created a massive export subsidy program, raised minimum agricultural support prices and idled, at the highest point, 33% of US farmland (Orden 2003). The experiences of 1981 and 1985 awakened policy makers to the influence government subsidies had on production and trade. The first real steps toward decoupling began in 1991 when farm payments no longer increased as farmers raised their crop yields. The 1991 bill began to give farmers marginal flexibility in their planting decisions in exchange for reduced subsidies. The 1996 farm bill moved further towards decoupling. Driven by high prices, strong exports, budget deficits 1 The projections assume no Doha Agreement, and all direct payments are notified as Green Box. Projections calculated by David Blandford and Timothy Josling, September 2008. 2 and a Republican majority that eschewed government involvement in the economy, the 1996 farm bill completely decoupled a portion of farm payments from production (known as Agricultural Market Transition Accounts or AMTA payments). The bill called for these payments to decline over a five year period, in theory to give farmers time to adjust to market forces. The bill coincided with the conclusion of the Uruguay Round and was touted as a new direction for US farm policy. However, this new direction proved unsustainable as prices fell in 1998, and was essentially undermined by the 2002 farm bill. The dynamics of the 1996 farm bill debate are helpful in understanding the 2002 and the 2008 farm bill debates. In 1995, commodity prices were so high that no payments would have been made under the 1991 farm legislation. Moreover, the 1991 farm bill required farmers to take land out of production in exchange for receiving subsidies — with high prices, farmers were losing money on land they were not allowed to farm. Farmers were also frustrated with farm policies that limited their planting flexibility. Farmers needed the 1996 farm bill reforms to eliminate mandatory landidling programs, so they could take advantage of high commodity prices, to allow planting flexibility so they could plant the most remunerative crops, and to make direct payments that were not related to prices, so they could still receive subsidies. More importantly, US budget rules meant that if no payments were made to farmers under the old farm bill, future US agricultural budgets would have to be cut. So, in order to keep money in the agricultural budget baseline, farm programs had to be de-linked from prices. In keeping with the Republicans’ free market philosophy, the direct payments were supposed to provide farmers with a transition to the market, declining over time and eventually falling to zero. While hailed as a victory for decoupling, Freedom to Farm did not last long. When prices began to fall in 1998, the farm community demanded emergency relief. In response, Congress added an average of $13 billion in subsidies back to the farm programs between 1998 and 2001. By 2001, the farm bill was distributing $38 billion annually to farmers alongside $38 billion to low income Americans. The 1996 Farm Bill turned out to be a marriage of convenience. Even though farmers needed decoupling to keep money in the agricultural budget, most farm groups and Members of Congress never embraced decoupling as a concept. They did not like the fact that the decoupled payments were to be phased out. They did not like the fact that the payments did not increase when prices fell. Some did not like it because it represented “welfare” to farmers since there were no planting requirements. The agribusiness groups who supported decoupling wanted to see acreage set-asides eliminated and wanted to see high commodity support prices reduced. They were willing to take farmers on, as long as the argument was about policy and not about money. But, for most of the Members, decoupling was an expedient way to get more through-put and to reduce the role of the government in the marketplace. Other changes in the 1996 farm bill — marketing loans in particular — mollified agribusiness leaders who were mainly concerned that the government policies were interfering with supplies and prices. By 2002, the US budget was in surplus, although as the farm bill debate got underway, everyone in Washington knew that budget deficits were looming. Again, in order to keep money in the agricultural budget, the farm bill needed to be reformed again, this time by making the emergency payments permanent. These transfers - which became known as counter-cyclical payments increase when prices fall. Target prices and support prices were increased, and direct payments became a permanent fixture of US farm programs. Agribusiness groups stood idly by, since no one 3 was threatening a return to supply controls, or to government dictated planting restrictions. Furthermore, the agribusiness companies did not want to get into an ugly fight with farmers over how much money they deserved. Marketing loans made sure that the government did not accumulate stocks, or prop up prices. Agribusiness groups that were happy to reform policies in 1996 did not want to be accused of taking away money from farmers in 2002. Not only did the 2002 Farm Bill stop the long-standing trend toward decoupling, it also attracted global condemnation for increasing farm subsidies, just one year after the launch of the Doha Development Agenda. A convergence of factors led reformers to hope that the 2008 farm bill would bring true reforms. The Doha Development Agenda was stalled, largely over agricultural subsidies. The Bush Administration had made the global trade talks a centrepiece of its global economic policy. Brazil had recently won a landmark case against US cotton subsidies which required the US to reform the cotton program. There was mounting evidence that US farm subsidies were negatively affecting farmers in developing countries; that they were going to the wealthiest farmers; that they did little for rural communities; that they did not support the crops (namely fruits and vegetables) that Americans were being urged to consume; and that they were not supporting environmental or conservationist goals. All of these forces led many to think that the 2008 farm bill would return to the path set out in 1981. Reformers also believed that the costly Iraq war combined with huge budget deficits and a “pay-asyou-go” budget system that made it impossible to propose new funding without new tax increases would put further pressure on antiquated and expensive farm programs. They thought that historically high farm incomes, land prices, and commodity prices in 2008 would demonstrate that most farmers did not need government support. (Reformers also believed that the biofuels boom would provide another market outlet for farmers, making the counter-cyclical and marketing loan programs irrelevant as prices for corn and other commodities surge as more farmers switch to corn and away from other commodities such as wheat, cotton and soybeans.) Finally, reformers thought that a Republican Administration with a pro-reform Secretary of Agriculture, coupled with a Democratic Congress that campaigned on its concern for poor Americans, would bode well for change. Each of these hopes encouraged different groups to decide to participate in the farm bill debate. Religious and charity groups like Bread for the World, Oxfam and the Catholic Bishops focused on the impact of farm subsidies on the poor in Africa and Asia. Environmental and conservation groups like the American Farmland Trust and Environmental Defense supported conservation and environmental measures. (Even the AFL-CIO - the major labour union in the United States - asked for more conservation funding since 70 percent of its members hunt and fish and depend on the Conservation Reserve to provide wildlife habitat.2) Groups like the American Dietetic Association and medical doctors weighed in on nutrition and obesity. The Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) talked about rural economic development. The Family Farm Coalition pushed for limits on payments to rich farmers. Citizens’ groups such as Taxpayers for Common Sense and Citizens against Government Waste pushed for reform on budgetary grounds. Business groups like the Grocery Manufacturers saw an opportunity to push for sugar and dairy reform to lower their input costs. 2 (http://www.farmpolicy.com/?p=297#more-297) 4 From past history, each of these groups knew that reforming US farm policy would be difficult. Powerful commodity groups provide vast financial support to members of Congress, and members of Congress favourable to farmers’ interests dominate the House and Senate Agriculture Committees, as well as the Senate Budget and Finance Committees. CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS MIRROR PROTECTION (2004 Election Cycle) Commodity Political Campaign Contributions (PACs only) Government Share of Farm Revenue Sugar $2,375,000 53-62% Dairy $1,757,000 38-56% Cotton $479,000 36-52% Rice $283,000 18-52% Wheat $100,000 22-48% Corn $37,000 13-34% Soy $17,000 14-28% Sources: Center for Responsive Politics/Federal Elections Committee OECD Producer Subsidy Equivalent Database Robert Thompson, U of IL John Baffes, The World Bank 5 Figure 2: Commodity group contributions to Which Industries Give? 20% 7% 7% 66% * “Other” includes specialty crops, wheat and primary processors Sugar Cotton Rice Other* Source: Center for Responsible Politics 2007 8 5 So, these groups came together in an unprecedented alliance, known as the Alliance for Sensible Agricultural Policies or ASAP (which is also the acronym for As Soon As Possible). Together they worked to educate their constituents about the impact of US farm subsidies on other objectives. They succeeded in generating 300 pro-reform editorials in 48 states, and throughout rural America, with 105 coming since July 2008, in response to the House-passed farm bill. They worked together on media and advocacy strategies as the farm bill debate unfolded. As a result of their advocacy efforts, several reform-minded proposals were developed and considered by Congress. Despite all of the positive factors, and this historic “strange bedfellows” alliance, farm policy reforms did not move away from Amber Box subsidies. An income cap was placed on Amber and Green Box payments to farmers and funding for (Green Box) nutrition and environmental programs was increased. But loan rates and target prices were increased. Under the current price environment, these higher prices do not trigger payments; nevertheless they are policy structures that would increase Amber Box subsidies should prices return to more historic levels. In addition a new revenue insurance program (ACRE) was created, which will also be in the Amber Box. Farmers can update their base acreage (which links production back to prices), and the planting flexibility programs which were questioned by the Brazil cotton decision were subject to only limited reforms. Ironically, some of the initiatives have undermined the case for the very same direct payments that WTO negotiations have encouraged. In 1995 the Environmental Working Group began to publish data on subsidy payments made to individual farmers. The EWG’s website showed what economists had always known, that farm subsidies linked to production would favour the farmers with the highest levels of production. The EWG’s website showed that the top 10% of US farms collect three-quarters of all agricultural subsidies. Stories about the inequity of US farm programs began appearing in the press, reached a crescendo in the run up to the 2008 farm bill debate. Stories detailed individual farmers’ subsidy payments; stories also reported that only certain crops were eligible for subsidies, and pointed out that the income and wealth of subsidy recipients is many times that of average Americans. But, in and of themselves, the EWG data did not particularly implicate decoupled payments. However, ground breaking investigative reporting by the Washington Post, the Atlanta Constitution and others uncovered stories of payments to made dead farmers and payments to farmers “growing” houses in suburban subdivisions. An article in the Washington Post based on USDA data found that $1.1 billion was distributed to dead farmers between 1999 and 2005. The article highlighted former farmland that had been divided into housing subdivisions that still qualified for farm subsidies, even though no crops had been grown for years.3 Then-Secretary of Agriculture Mike Johanns presented evidence that many subsidy recipients lived far from their ‘farms’: six people on Park Avenue collected over $250,000 per year in farm subsidies. Taxpayers for Common Sense analyzed farm subsidy data and found that only 15 percent of all farmers received subsidies, and of those (since farmers producing fruit, vegetables and livestock typically receive none), just 8 percent received 78 percent of all subsidies.4 When prices began to increase in 2006, reporters and editorial boards began asking why farmers received government checks when they did not really “need” them. More importantly, perhaps, as commodity prices rose, the direct payments represented a source of funds for other priorities. 3 4 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/07/22/AR2008072201128.html http://www.taxpayer.net/agriculture/learnmore/factsheets/agpolicy.pdf 6 In the run-up to the 2008 farm bill debate, several of the reform groups began to develop new ideas for subsidy reform. Conservationists developed proposals to link payments more explicitly to conservation measures. They proposed fully funding the Conservation Security Account, which made payments to farmers to offset the costs of environmental measures: this account was instituted in the 2002 farm bill, but never fully funded. Conservation groups wanted to transfer some of the money going to commodity programs (including direct payments) to fully fund this program. Demands to create a Conservation Security Account that would pay farmers for conservation further undermined the case for direct payments made to farmers for doing “nothing.” Other groups developed revenue insurance programs on the theory that these would be less trade distorting than traditional counter-cyclical or marketing loan programs. The Integrated Farm Revenue Program proposal developed by the American Farmland Trust eliminated the marketing loan and counter-cyclical programs and replaced them with a National Revenue Deficiency Program that would make payments to farmers only when the national revenue of a particular crop fell below the expected national target revenue, thus replacing static target prices with moving target revenue (i.e. price times yields). Payments would be made only when a farmer’s total crop revenue fell below the target. Because these payments are not known in advance, farmers’ decisions would be market driven. A similar proposal was adopted by the National Corn Growers Association. Another proposal known as FARM21, developed by Environmental Defense, would have replaced counter-cyclical and direct payments with risk management accounts that farmers could access if their income dropped below 95 percent of a rolling five year average. Because of this, FARM21 was considered the least trade distorting and most market oriented of the various reform proposals. As the 2008 farm bill debate began, these and other proposals were on the table. But in the early days of the debate, most farm groups called for a simple extension of the 2002 farm bill. Once again however, budget dynamics intervened. As commodity prices began to increase, payments under the counter-cyclical and marketing loan programs fell for most crops (in some cases to zero). It became increasingly clear to the commodity groups that extending the 2002 farm bill would mean less money for future agricultural budgets. Mainstream commodity groups began to argue for higher support and higher target prices that would provide a “safety net” in times of low prices. Farmers from the vulnerable Northern Plains states began pushing for permanent disaster aid — again, in part to capture agricultural budgets that would evaporate if the 2002 farm bill were extended. Despite all the elements arguing for fundamental reforms, the House version of the 2008 Farm Bill (approved in July 2008) represented a further retreat from decoupling. Given the seemingly positive environment for reform, what happened? First, while the members of the Alliance for Sensible Agricultural Policies all supported farm bill reforms, they supported reforms for vastly different reasons. While all agreed that commodity programs needed to be reduced, some wanted more money for nutrition programs, others for conservation programs, and still others for deficit reduction. These groups did agree on how to divvy up the savings from commodity reforms, and ultimately, most of the reform groups supported the FARM21 proposal (sponsored by Ron Kind and Jeff Flake). But that legislation proved too radical a departure for members of Congress to support. 7 Second, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi turned the farm bill into a test of Democratic Party loyalty. In exchange for support of various groups, additional funding was made available. For example, the Congressional Black Caucus received $100 million to settle discrimination lawsuits filed by African Americans against USDA. Nutrition groups got $4 billion in food stamps and enhanced child nutrition programs; the popular Conservation Reserve Program was increased by 3 million acres. The Conservation Security Program was expanded. Congress added $1.8 billion in subsidies for fruit and vegetable farmers and introduced country of origin labelling on fruits and vegetables. These offers were enough to convince many reform-minded members of Congress to support the House passed farm bill. Most of these proposals were supported by the Senate, and found their way into permanent legislation. The Farm Bill offers producers the option of enrolling in a new revenue-based countercyclical program rather than the current price-based counter-cyclical program. The bill excludes payments to farmers making over $1 million in adjusted gross income; it eliminates a rule that allowed farmers to collect double payments; and it halved the payment cap per farmer for direct and counter-cyclical payments. However, these reforms will have little impact on overall payments: while the overall subsidy cap was lowered, limits on direct payments were raised from $40,000 to $60,000, and the $75,000 limit on marketing loan payments was eliminated altogether. Increases in nutrition spending and in conservation spending both shifted more funds into Green Box subsidies; but the bulk of changes in the commodity programs have the potential to further increase US Amber Box spending. The Farm Bill did not bring US policies into compliance with the WTO cotton ruling. The exemption that prevents commodity crop farmers from planting fruits and vegetables on land receiving commodity payments was not changed. The most recent and final WTO finding that the US has not complied with the cotton panel means that the failure to address this will become more of an issue. The Farm Bill also raised marketing loan rates and target prices, further insulating farmers from market signals and potentially increasing Amber Box payments, should commodity price levels fall. Finally, the sugar support price was increased. It is significant that President Bush chose to veto the farm legislation (something he had to do twice because of a clerical error). But it is also significant that in both cases, Congress overrode the veto with sizeable margins. As a result, subsidy payments will continue to go to the major commodity crops, in particular corn, cotton, sugar, soybeans and wheat, concentrated in the Midwest and South. Seven states collected over half of the subsidies distributed from 2003-2005 (Environmental Defense 2008). Figure 2 shows the concentrations of farm subsidies across the US, with the Midwest and the South receiving the highest amounts of subsidies. 8 Figure 3: Farm Subsidies by State, 2003-20055 A preliminary analysis of the 2008 farm bill indicates that — if commodity prices were to fall — the likelihood of a WTO challenge would actually increase because marketing loans and revenuebased counter-cyclical programs, as well as higher target prices for certain crops have the potential to significantly affect markets, production, and trade (Sidley and Austin, 2008). According to the analysis, prices of the five major commodities would not have to fall far to fall to be vulnerable to a WTO challenge. Direct payments, while less likely to be challenged than Amber and Blue Box subsidies, nevertheless are vulnerable to challenge. Direct payments as currently constructed continue to violate the terms of the cotton agreement, as pointed out in a Sidley and Austin analysis of prospective US Farm policy. In addition, other policies notified as Green Box could also be challenged, including existing crop insurance and quite possible the new revenue insurance program. Finally, “the cumulative effect of the price-contingent subsidies, crop insurance and disaster assistance would likely find that such subsidies ensure that farmers are protected from most types of harmful fluctuations in their revenue.” Farmers produce more than they would under normal circumstances because they are insulated from risk, which distorts world markets. So the cumulative impact of Green, Blue and Amber box subsidies could be challenged at the WTO. In a recent analysis by David Blandford and Tim Josling (2008), under the most ambitious agriculture reductions proposed in the Falconer paper, the US would not have to reform its agricultural policy until 2012 at the earliest—assuming prices remain strong. A subsequent analysis which assessed the impact of the May 2008 Falconer paper on the 2008 farm bill confirms this finding (Blandford, Laborde and Martin, 2008): the limits on Overall Trade Distorting Support will not become binding, even at the end of the Doha implementation period, but the “water” will be reduced significantly. However, Amber Box limits would become binding for cotton and sugar — both of which are important to developing countries and politically sensitive for the United States. 5 Data for this chart was taken from the Environmental Working Group’s Farm Subsidy Database. 9 But, with the suspension of the Doha negotiations, it is unclear whether and when the types of proposals on the table in the negotiations will be agreed. Figure 4: A Doha Deal Would Constrain US Subsidies by 20136 US projected notifications and WTO limits - Falconer A 90 80 Billion $ 70 Green Box Total AMS AMS limit Blue Box Blue Box limit OTDS OTDS limit 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 In part, the reverse box shifting in the 2008 farm bill is because of the nature of the US budget process: policies are shaped in order to get the most money from that year’s budget and to retain budget authority over the longer term. In part it is due to farmers’ memories after the 1996 Farm Bill when prices fell sharply, when they felt that direct payments did not sufficiently compensate for the fall in income. The notion of a safety net that operates only when farmers “need it” has a great deal of emotional and political appeal. The fact that such a safety net would likely be Amber Box is of little moment in US politics. But at another level reverse box shifting is due to a lack of alternative ideas. The 2008 reform movement came together mostly because the groups opposed the current commodity programs, but they had too many ideas of how to fix it, why it needed fixing, and what they wanted it to do instead. The concept that tax revenue should provide for public goods that are available to the citizenry as a whole and not be transferred to a few private citizens - or “public money for public goods” - has become a mantra in European policy reform circles, but did not take hold in the United States. The notion that public spending be used to improve the competitiveness of farmers, to support the economic vitality of rural areas or to promote environmental sustainability did not garner sufficient support either (Johnson and Runge, 2008). In a recent paper, Johnson and Runge develop these arguments more fully. They argue that for many farmers, the private market should step in where the government has heretofore provided support. In particular, private risk management tools can take over from public systems such as price, yield and revenue insurance schemes (Johnson and Runge). They argue that private insurance schemes would develop if public spending did not crowd out the market. In their view, farm policy should evolve from an income support system for all farmers to one that differentiates between farmers in different categories. Large commercial farmers would not continue to benefit from programs originally intended as welfare support for smaller farmers. This is particularly true for 6 The projections assume no Doha Agreement, and all direct payments are notified as Green Box. Projections calculated by David Blandford and Timothy Josling, September 2008. 10 150,000 farms that earn over $250,000 per year and account for 70 percent of US farm policy benefits (Johnson and Runge, 2008). Instead, the US government would concentrate its efforts on improving productivity and the long-term competitiveness of US agriculture Before the recent financial crisis, many argued that with a cheap and falling dollar, low commodity stocks, with increasing demand for commodities (in part due to biofuels mandates), and a long term forecast of robust economic growth in consumer demand in China and India, it was a propitious time for the US to reform its subsidy policies. The global economic slowdown is depressing commodity prices, although not yet to levels that will trigger farm payments. Should payments be triggered, the emerging US budget deficit may force Congress to make cuts in commodity programs under the guise of deficit reduction that they could not make under the farm bill. But it is equally straining the US budget. Unfortunately, US farmers have chosen to retain a status quo farm policy that does not look forward to the 21st century. 11 Bibliography Blandford, David and Tim Josling (2008). “Meeting Future WTO Commitments on Domestic Support: The Implications of Ambassador Falconer’s July 2008 proposals for the European Union and the United States.” German Marshall Fund Paper Series, September 2008. Blandford, D, Laborde, D and Martin, W, (2008). Implications for the United States of the 2008 Draft Agricultural Modalities. International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, Geneva, Switzerland. Environmental Defense (2008). “Ways to improve America’s farm and food policies.” Environmental Defense Fact Sheet. Available online at http://www.environmentaldefense.org/documents/7026_Fact%20Sheet_National.pdf Johnson, Robbin and C. Ford Runge (2008). “The Next Farm Bill: Will it look backward or forward?” Prepared for the Wilson Center for Scholars Perspectives on the 2008 farm bill. Accessible at: http://www.wilsoncenter.org/events/docs/The%20Next% 20 Farm %20Bill%20Will%20it%20Look%20Forward %20or%20Backward.doc Orden, David (2003). “U.S. Agricultural Policy: The 2002 Farm bill and the WTO Doha Round Proposal.” IFPRI TMD Discussion Paper 109. Sidley and Austin (2008), Legal Analysis performed for Environmental Defense, July 2008 12