Philosophy and the Search for Meaning

advertisement

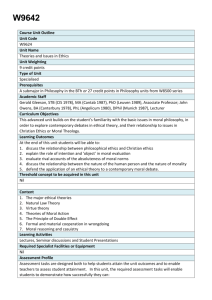

Lecture Objectives: After learning this material you will be able to: 1. Understand the definition of ethics as the study of right and wrong and how to live the good life. 2. Discuss the major features of noncognitive and cognitive ethical theories, especially noting the differences between relativist and universalist theories. 3. Present the central importance of approaching a study of ethics with an open mind. 4. Be able to recognize the chief features of different metaphysical viewpoints, such as dualism and materialism, in how we understand ethics. 5. Discuss the importance of the contributions of sociobiologists, behaviorists, and determinists to the traditional study of ethics by philosophers and theologians. In the last lecture I wrote a general introduction to philosophy, outlining philosophy as a search for, and a love of, wisdom. I also explained about the “indestructible question” and “the science of awareness.” We will see in this lecture how important this is to our study of ethics. In our first lecture I also wrote about ideas concerning the evolution of consciousness. It will be important to note that the transition from a mythological consciousness to a rational consciousness necessarily changes the way we view ethics. Finally, we begin this lecture with a reminder that how we view ethics tells us a great deal about how we view ourselves because ethics touches our deepest values. The study of ethics, therefore, is not simply intellectually stimulating, but it is ultimately practical because this study can change us on a very deep level. Nothing could please the great Greek philosopher Aristotle more. Aristotle wrote: “The ultimate purpose in studying ethics is not as it is in other inquiries, the attainment of theoretical knowledge; we are not conducting this inquiry in order to know what virtue is, but in order to become good, else there would be no advantage in studying it” (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Bk. 2, Ch. 2) quoted in (Judith A. Boss, Ethics For Life: A Text With Readings, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2008] p. 3. Hereafter referred to as Boss). Aristotle taught that ethics is meaningless if it does not lead to ethical practices and living a good life. In this day and age of financial, political, and religious scandals it is important for us to ask ourselves: is there still a way for ethics to play a role in the modern world? This is a question we will keep close to us throughout the remainder of this course. In the meantime we need to start at the beginning. What Is Ethics? Some people will separate ethics and morality into two different definitions, ethics being secular in origin and morals being religious in origin. But that is more technical than necessary and these two words will be used interchangeably in 1 this class. “The term ethics has several meanings. It is often used to refer to a set of standards of right and wrong established by a particular group and imposed on members of that group as a means of regulating and setting limits on their behavior. This use of the word ethics reflects its etymology, which goes back to the Greek word ethos, meaning ‘cultural custom or habit.’ The word moral is derived from the Latin word moralis, which also means ‘custom’” (Boss, p. 5.) One of the questions we have to entertain is to wonder if ethics are only a matter of custom or try to discover if they are universal or not. We will discuss this further below. In the meantime it is fair enough to say that our first glimpses into what is right and wrong usually stem from what those around us think about these things. “The identification of ethics and morality with cultural norms or customs reflects the fact that most adults tend to identify morality with cultural customs. Philosophical ethics, also known as moral philosophy, goes beyond this limited concept of right and wrong. Ethics, as a philosophical discipline, includes the study of the values and guidelines by which we live and the justification for these values and guidelines. Rather than simply accepting the customs or guidelines used by one particular group or culture, philosophical ethics analyzes and evaluates these guidelines in light of accepted universal principles and concerns” (Boss, p. 5.) The interest in universal principles comes from realizing that whole cultures have considered things such as slavery a good when it is now condemned. Did the nature of what is good change? Or did people’s understanding of the good change? Is something good because it is good in itself? Or is it good because we as a people agree that it is good? The question about what is good is closely connected to the question about what it means to be human. We don’t usually think of animals being “bad” or “sinful” when they kill for example. But we do worry about humans who kill except when they do so in self-defense. What is the difference? The difference relates to our human nature and our ability to use our reason in deciding how we want to live. “Ethics is a way of life. In this sense, ethics involves active engagement in the pursuit of the good life - a life consistent with a coherent set of moral values. According to Aristotle, one of the leading Western moral philosophers, the pursuit of the good life is our most important activity as humans” (Boss, p.5.) Socrates taught that the unexamined life was not worth living. In other words, what makes humans unique, supposedly, is our ability to self-reflect, analyze, and adjust our behavior. Our ability to grow, learn, and change is one of the most amazing things about human nature. We can get frozen in our growth or live just according to our instincts, but we don’t have to. This is why the ethical life was so important to Aristotle. “Aristotle believed that ‘the moral activities are human par excellence.’ Because morality is the most fundamental expression of our human nature, it is through being moral that we are the happiest. According to Aristotle, it is through the repeated performance of good actions that we become moral (and happier) 2 people. He referred to the repeated practice of moral actions as habituation. The idea that practicing good actions is more important for ethics education than merely studying theory is also found in other philosophies, such as Buddhism” (Boss, pp. 5-6.) The important insight here is that if you want to be good you have to act good, whether you feel like it or not. By doing good acts, you eventually become a good person. You then do the right thing because you want to do so rather than under duress. A popular saying along these lines is that “you have to fake it until you can make it.” Sometimes people wish for things for themselves morally. People, for example, wish they could be a better friend. But just wishing it (while a start!) will not take you very far. You actually have to think about the qualities of a good friend, qualities such as loyalty, generosity, being a good listener, being trustworthy, and then actually practice these things. After a while you find that people trust you more because you have become trustworthy! Let’s dig in to our subject by looking into some technical terminology. Normative and Theoretical Ethics There are two basic approaches to ethics. The first is more abstract and studies the nature of goodness itself. The second is more practical and looks at specific actions. “Theoretical ethics is concerned with appraising the logical foundations and internal consistencies of ethical systems. Theoretical ethics is also known as metaethics; the prefix meta comes from the Greek word meaning ‘about’ or above.’ Normative ethics, on the other hand, gives us guidelines or norms, such as ‘do not lie’ or ‘do no harm,’ regarding which actions are right and which are wrong. In other words, theoretical ethics, or metaethics, studies why we should act and feel a certain way; normative ethics tells us how we should act in particular situations” (Boss, pp. 7-8.) We will be concerned with both kinds of ethics in this course as we are studying ethics in an academic setting. But I am hoping that between examples I use in the lectures and through the case studies of ethical issues you study in our text, you will gain an appreciation for how practical and necessary ethics really is in our world today. Abstract ethics starts by trying to determine where ethical insights come from. As a result it quickly divides into two basic categories. “Metaethical theories can be divided into cognitive and noncognitive theories. Noncognitive theories, such as emotivism, claim that there are no moral truths and that moral statements are neither true nor false but simply expressions or outbursts of feelings. If moral statements are neither true nor false, there is no such thing as objective moral truths” (Boss, p. 8.) Many people have come to this conclusion. This is especially true for those people, such as psychologists, who are aware of how much people can rationalize almost any behavior. Because we can use our minds to rationalize good or bad behavior these people think that our sense of morality must come from our feelings. In philosophy there was a whole movement called 3 Romanticism that stressed the importance of feelings as being our surest way to understand the world. However, most philosophers are aware that feelings, too, can be deceptive and that the mind is not the problem so much as the wrong use of the mind. The goal then becomes to understand moral reasoning so as to make proper use of human rational capacities. “Cognitive theories maintain that moral statements can be either true or false. Cognitive theories can be further subdivided into relativist and universalist theories. Relativist theories state that morality is different for different people. In contrast, universalist theories maintain that objective moral truths exist that are true for all humans, regardless of their personal beliefs or cultural norms” (Boss, p. 8.) This issue of relativism versus universalism will be something we will have to return to again and again. We live in a culture that is permeated by what is often called “cultural relativity.” This is the belief that different things are right for different groups of people at different times. We will see that this makes a certain amount of sense. But this belief is also attacked because it can be used to justify all sorts of unethical behavior on the basis of our not being in a position to judge whether something is bad or not. For example, slavery has now been outlawed around the world. But does that mean it has only recently become wrong? Or was it always wrong? We need to look closely at both universalistic theories and relativistic theories. Relativist Theories If you believe that what is wrong for you might nevertheless be O.K. for someone else then you might be a relativist. “According to the relativist theories, there are no independent moral values. Instead, morality is created by humans. Because morality is invented or created by humans, it can vary from time to time and from person to person. Ethical subjectivism, the first type of relativist theory, maintains that moral right or wrong is relative to the individual person and that moral truth is a matter of individual opinion or feeling. Unlike reason, opinion is based only on feeling rather than analysis or facts. In ethical subjectivism, there can be as many systems of morality as there are people in the world” (Boss, pp. 8-9.) This is a very popular way of viewing the world, especially by the younger generations, so we will have to pay close attention to it and see what we can learn about its basic insights and values. Sometimes people are relativists, but not on the individual level. They don’t think there is a different morality for every individual person, but they do see different cultures as having different ethical systems. “Cultural relativists, on the other hand, argue that morality is created collectively by groups of humans and that it differs from society to society. Each society has its own moral norms, which are binding on the people who belong to the society. Each society also defines who is and who is not a member of the moral community. With cultural relativism, each circle or moral system represents a different culture” (Boss, p. 9.) People who do not agree with the behavior of gangs in American cities can still see how 4 within the gang culture they have their own ideas about what is right and wrong even if those ideas conflict with mainstream American culture. Most people think of religions as believing in absolute morals. But when you study the world’s religions, you start to see that the picture is more complicated. “A third type of relativist theory is divine command theory. According to this theory, what is moral for each person or religion is relative to God. There are no universal moral principles that are binding on all people. Instead, there is no morality independent of God’s will, which may differ from person to person or from religion to religion” (Boss, p. 9.) Is it God’s will that women be veiled from head to foot when out in public? Some religions say yes and some say no. In the United States women can veil themselves or not. It is left up to personal choice and becomes an example of relativism. Hopefully you are seeing that relativism is more complex than people often think. “Ethical subjectivism, cultural relativism, and divine command theory are mutually exclusive theories. When theories are mutually exclusive, a person cannot consistently hold more than one of the theories to be true at the same time. For example, either morality is created by the individual and the opinion of the individual always takes precedence over that of the collective, or else morality is relative to one’s culture and the moral rule of the culture always takes precedence over that of the individual” (Boss, p. 10.) When it comes down to ethics, not choosing what to think or how to act is a choice! You can’t really sit this one out, although this is exactly what some people think they can do. But when analyzed we see that all people come down on one side or another. But relativism is not your only choice. Universalist Theories For most of human history people have thought of good as absolute. This is one reason why people felt free to impose their own moral values on other people. This confidence comes from the sense of universality. “Universalist theories, the second group of cognitive theories, maintain that there are universal moral values that apply to all humans and, in some cases, extend beyond the human community. Morality is discovered, rather than created, by humans. In other words, the basic standards of right and wrong are derived from principles that exist independently of an individual’s or a society’s opinion” (Boss, p. 10.) We can see these truths in math and geometry. A triangle didn’t have three sides because we decided it did. A triangle always had three sides. That is what makes it a triangle and our opinions about that do not matter. It is what it is. Universal ethical values share this solidity that math has and this is one of the reasons why some people like these values so much. “Unlike relativist theories, most universalist theories include all humans in their moral community rather than only those living in their society, as often happens in cultural relativist theories. The moral community is composed of all those beings that have moral 5 worth or value in themselves. Because members of the moral community have moral value, they deserve the protection of the community, and they deserve to be treated with respect and dignity. Because the basic moral principles are universal, universalist theories can be represented by one circle that includes individuals from all cultures” (Boss, p. 10.) People who believe in universal values believe that something like slavery is wrong not, just where it is recognized as wrong and thus made illegal. It is wrong everywhere. This is an issue for those who are concerned about human rights. They believe that what they recognize as rights here in the United States (such as freedom of speech) should be recognized everywhere. Notice the word “should.” Should is a prescriptive word, that is, it tells us what we should do, and in that way it is related to ethical values. One of the main concerns with universalism is that it can quickly become dogmatic and lose sight of the complexity about different moral concerns. “Theories, by their very nature, oversimplify. A theory is merely a convenient tool for expressing an idea. Some theories are better than others for explaining certain phenomena and providing solutions to both old and new problems. When studying the different moral philosophers, we must be careful not to pigeonhole their ideas into rigid theoretical boundaries” (Boss, p. 11.) There is a phrase that expresses this: “Rules are made to be broken.” In other words, there are exceptions and you have to be sophisticated and intelligent in how you view morality so that you can live a good life while at the same time knowing how to be flexible. A simple example: In a law-abiding society we expect people to obey the rules, such as stopping at red lights. If everyone disobeyed this we would have chaos and it would be very dangerous. But there are times, such as when rushing to a hospital in an emergency, when we expect people to be able to evaluate the good of obeying a law and the good of saving a life and see that saving a life is more important. When people become dogmatic they sometimes lose sight of this. Ethics is based on a worldview, a picture of reality. As a result our ethics depend on how accurate our worldview is. This is why we can’t let our ethical theories become more important than the good that they are there to promote in the first place! “Theories are like telescopes. They zoom in on certain key points rather than elucidate the total extent of thinking about ethics. Because morality covers such a broad scope of issues, different philosophers tend to focus on different aspects of morality. Problems arise when they claim that their insight is the complete picture - that morality is merely consequences or merely duty or merely having good intentions. Morality is not a simple concept that can be captured in a nice tidy theory; it is a multifaceted phenomenon” (Boss, p. 11.) We will be looking at many theories in this class and there is sometimes a feeling of disappointment when an ethical theory gets criticized because we want it to work. But all theories are limited. The point of studying many of them is that we see how when we pull all of them together we start to get a bigger vision of what it 6 means to be a good person. We are able to include more perspectives, and that is usually a very good thing. Philosophy and the Search for Wisdom One of the things that is important to remember not only in ethics, but also in any philosophy class, is the importance of independent, critical thinking. You need to discover the nature of goodness for yourself. “In seeking answers to questions about the meaning of life and the nature of moral goodness, the philosopher goes beyond conventional answers. Rather than relying on public opinion or what others say, it is up to each of us, as philosophers, to critically examine and analyze our reasons for holding particular views. In this way, the study of philosophy encourages us to become more autonomous” (Boss, p. 12.) Some of the greatest evils in the world are not committed by “evil” people so much as by great crowds of people who go along with public expectations because they do not want to challenge authority or “rock the boat.” The goal of a philosopher should be self-realization or what Emerson called selfreliance. This is the ability to think for oneself and stand by your principles. If you can’t or won’t do that then you lose an essential aspect of your humanity and you become more like a machine than a person. “The word autonomous comes from the Greek words auto (“self”) and nomos (“law”). In other words, an autonomous moral agent is an independent, self-governing thinker. A heteronomous moral agent, in contrast, is a person who uncritically accepts answers and laws imposed by others. The prefix hetero- means ‘other’” (Boss, p. 12.) While most of us admire and even aspire to be an autonomous person, we all know that in reality it is much more difficult than it seems. The first step on the road to autonomy, however, is to start to see how beholden we are to the values of our family and culture. We see that long before we had the ability to think for ourselves we were simply given predigested values. “The road to wisdom, Socrates believed, begins with the realization that we are ignorant. In his search for wisdom, Socrates would stop people on the street to ask them questions about things they thought they already knew. In doing this, he hoped to show people that there was a difference between truth and what they felt to be true (their opinions). By exposing the ignorance of those who considered themselves wise, Socrates taught people to look at the social customs and laws in a new way. He taught them not to simply accept the prevailing views but to question their own views and those of their society in a never-ending search for truth and wisdom” (Boss, p. 13.) When we examine the values we are raised with we might very well end up agreeing with them and making them our own. This is good because now they will mean more to us. However, there may be other values that we decide do not ring true for us and interfere with our own integrity. In that case we will want to make changes. But in either case, through self-reflection and examination of the issues, we have come 7 closer to making values our very own. Hopefully a class like this one is only one step in the process of seeking the good. Self-Realization One of the things I really enjoy about teaching ethics is that it is the place in philosophy where “the rubber meets the road.” There is probably no quicker route to learning what a person’s philosophy is then to ask them about their values. “Some of the most important philosophical questions are those regarding the meaning and goals of our lives. What kind of person do I want to be? How do I achieve that goal? Many philosophers define this goal in terms of self-realization - also known as self-actualization and enlightenment. Self-realization is closely linked to the idea of moral virtue. According to psychologist Abraham Maslow, self-actualized people are autonomous. They do not depend on the opinions of others when deciding what to do and what to believe. Philosophers such as Socrates and Buddha exemplified what Maslow meant by a self-realized person” (Boss, p. 14.) In many ways, becoming a self-actualized person is more difficult in the modern world due the pervasiveness of popular culture and the media. Everywhere and seemingly all of the time we are bombarded with words and images all designed to influence us to think a certain way, desire certain things, behave in a manipulated fashion. The good news is that much of our exposure to all of this “noise” is up to us. We have the ability to turn off the computer, turn off the T.V. and take some time to think for ourselves. But it does take some discipline to do this. It helps to have access to important ideas, such as philosophy (!), that help remind us that we are human beings who can ask the great questions and not simply seek to be entertained. It is also helpful to remember that this is not a one-time thing. “Self-realization is an ongoing process or way of life. People who are self-actualized devote their lives to the search for ultimate values. Being honest involves the courage to be different and to work hard at being the best one can be at whatever one does. People who are lacking in authenticity or sincerity blame others for their own unhappiness, giving in to what French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir (19081986) called ‘the temptations of the easy way’” (Boss, p. 14.) One of the key ethical virtues is responsibility. But responsibility to others only becomes truly possible when we learn to take responsibility for ourselves. This is the problem with peer pressure. Instead of thinking for ourselves and acting on the basis of our own convictions the crowd pushes us along. For some reason the whole notion of peer pressure is usually reserved for young people, but the truth is that we are subject to it for our entire lives. We can see this especially well in looking and studying how attached we are to getting and keeping the approval of others. We can see it in our sensitivity to criticism and our willingness to learn and grow from the feedback we get from others rather than simply getting defensive. “People who are self-actualized, in contrast, are flexible and even welcome having their views challenged. Like true 8 philosophers, they are open to new ways of looking at the world. They are willing to analyze and, if necessary, change their views - even if this means taking an unpopular stand. This process involves actively working to recognize and overcome the barriers to new ways of thinking; chief among these is cultural conditioning” (Boss, pp. 14-15.) It can be really disturbing to see to what extent some of us will go to be accepted by others. This is probably the reason why different spiritual programs and different religions put so much emphasis on choosing our companions carefully. If people’s approval of us is a significant part of our lives then who those people are can be critical in the kind of ethics we practice. This makes sense even on the physical level. If we want to stay in shape it helps to be around other people who eat right and exercise. Of course there is always the danger of insulation and becoming closed off to different people and different views. So, as with so many things, we must work to find and then keep a balance in our efforts to become autonomous people. Skepticism Sometimes skepticism has a negative connotation. But that is only because it gets confused with cynicism. It really has more to do with openness. “Philosophers try to approach the world with an open mind. They question their own beliefs and those of other people, no matter how obviously true a particular belief may seem. Rather than accepting established belief systems uncritically, philosophers first reflect on and analyze them. By refusing to accept beliefs until they can be justified, philosophers adopt an attitude of skepticism, or doubt, as their starting point” (Boss, p. 15.) The goal is to find the truth and be open to learning more. All too often, however, skepticism does not represent an open mind but simply camouflages a despair of finding truth. “Cynicism is closed-minded and mocks the possibility of truth; it begins and ends in doubt. Cynicism denies rather than analyzes. In this sense, cynicism is a means of resisting philosophical thought because it hinders analysis” (Boss, p. 15.) Once again we see the need for truth. We don’t want to be closed to new ideas and fresh perspectives, but at the same time I am reminded of a saying of one of my favorite professors: “We want to have open minds, but not so open that our brains fall out!” People who are closed to truth usually don’t think ethics is based on anything worthwhile, certainly nothing greater than personal whim. But people who believe in a truth and in an ethics often think their search is over. This poses another kind of problem from the one posed by relativism. “Some people believe that morality demands a sort of rigid, absolutist attitude; in other words, a person should stick to his or her principles no matter what. However, if we believe that truth is constantly revealing itself to us - whether through reason, experience, or intuition - in our quest for moral wisdom, we must always be open to dialogue with each other and with the world at large. If we think at some point that we have found truth and, therefore, close our minds, we have then ceased to think like a true 9 philosopher. We will lose our sense of wonder and become rigid and selfrighteous” (Boss, p. 17.) The unfortunate effect of this attitude is that it comes down so hard on people who think differently about ethics that a dialogue becomes impossible. The irony is that the people who think their ethical viewpoint is very important need to convince others to go along, but they lack the skills to be able to persuade others. Buddhists talk about being able to communicate with “skillful means.” This means knowing how to communicate in such a way that others are able to take in our message. Another reason the search for truth is important is because even if our values feel certain to us the situations life offers us keep changing. For example, many of the world’s scriptures were recorded long before many modern problems came into existence with the birth of technology. We need to keep learning so that we can explore the new circumstances we find ourselves in. “For a philosopher to stop seeking truth is like a dancer freezing in one position because he thinks he has found the ultimate dance step or an artist stopping painting because she thinks she has created the perfect work of art. Similarly, to cease being openminded and wondering is to cease thinking like a philosopher. To cease thinking like a philosopher is to give up the quest for the good life” (Boss, p. 17.) The most interesting people are the ones who never stop learning. I teach many senior citizens at my local Community College, Monterey Peninsula College. I am always inspired by people in their seventies and eighties (and even a few in their nineties!) who are still reading and taking classes. They give me hope that life can be a long adventure of ever-new horizons of expanding knowledge and wisdom. Metaphysics and the Study of Human Nature Metaphysics is the study of ultimate reality and as a result many modern people think there is no place for it in our world today. Some authors have written about “the death of metaphysics.” The death is blamed on the advent of a scientific vision of the world that does not leave room for the divine. But this makes two mistakes. First, it limits and narrows science too much and, second, it limits metaphysics to only being accessible to traditionally religious people. But this should not be the case. “Ethical theories do not stand on their own but are grounded in other philosophical presumptions about such matters as the role of humans in the universe, the existence of free will, and the nature of knowledge. Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy concerned with the study of the nature of reality, including what it means to be human” (Boss, p. 19.) Therefore, anyone who is interested in these questions, whether religious or not, is interested in metaphysics. This is important because how we view the world is a major factor in what kind of ethics makes sense to us. For example: are humans free or determined? Obviously we are limited and conditioned by some things, but are we entirely conditioned? How we answer that question has important implications for what it means to be a good person. 10 “Our concept of human nature has a profound influence on our concept of how we ought to live. Are humans basically selfish? Or are we basically altruistic? What is the relationship between humans and the rest of nature? Do humans have a soul? Or are we purely physical beings governed by our instincts and urges?” (Boss, p. 19.) These are some of the questions we must wrestle with. People who think philosophy is too abstract and has nothing to do with “the real world” have not studied ethics! “Metaphysical assumptions about the nature of reality are not simply abstract theories; they can have a profound effect on both ethical theory and normative ethics. Metaphysical assumptions play a pivotal role, for better or for worse, in structuring relations among humans and between humans and the rest of the world” (Boss, p. 19.) Because of this it is important to briefly look at two very basic and very different ways of looking at the world, dualism and materialism. Metaphysical Dualism If you grew up in the Western world, there is a good chance that you are a dualist, whether you know it or not. “According to metaphysical dualists, reality is made up of two distinct and separate substances: the material or physical body and the nonmaterial mind, which is also referred to as the soul or spirit. The body, being material, is subject to causal laws. The mind, in contrast, has free will because it is nonmaterial and rational. Some philosophers believe that only humans have a mind, and hence, only humans have moral value. The belief that adult humans are the central or most significant reality of the universe is known as anthropocentrism” (Boss, p. 19.) We know that the body is not free. Walk off a cliff and you will fall whether you want to or not. You have no choice because your body is subject to physical laws, such as the law of gravity. So what is free to make moral choices? Something not material? Thus dualism! So if many of us tend to take dualism for granted, whether we think about it or not, then why is there another main metaphysical theory? “One of the main problems with dualism is coming up with an explanation of how two apparently completely different substances - mind and body - are able to interact with each other, especially on a causal level. Because of the mind-body problem, many philosophers have rejected dualism” (Boss, p. 21.) In other words, how does a thought bring about a result in a physical body? We still do not have the answer to this problem, which continues to be studied by people exploring the brain and the nature of consciousness. In the meantime, some people have looked elsewhere. Metaphysical Materialism If our reality is not two separate things then it must be one thing! “There are many variations of nondualistic or one-substance theories. One of the more popular one-substance theories is metaphysical materialism. In this worldview, 11 physical matter is the only substance. Therefore, materialists do not have to deal with the mind-body problem. On the other hand, materialists have a difficult time explaining the phenomenon of consciousness. Because metaphysical materialists reject, or consider irrelevant, abstract concepts such as mind or soul, morality must be explained in terms of physical matter” (Boss, p. 21.) Scholars who believe this study the brain to find a way to understand consciousness. It is an interesting question to wonder if the brain produces consciousness or if it simply manifests through a brain. For example, if you turn on your television you don’t think your television is producing the shows! You know the shows are produced somewhere else and that your T.V. can simply tune into them. If you turn off the T.V. the show does not stop wherever other people are watching it on different television sets. It just means you no longer have access to it. Does the brain function like a T.V.? This question is still unsettled. Groups of people who think the brain produces consciousness are still trying to figure out how it all works together. “Sociobiology is based on the assumption of metaphysical materialism. As a branch of biology, sociobiology applies evolutionary theory to the social sciences - including questions of moral behavior. Sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson claims that morality is based on biological requirements and drives” (Boss, p. 21.) If you have ever studied the chemical nature of our emotions, this seems to be an interesting possibility. All emotions seem connected with certain chemicals. Anger is the easiest to verify. If you get really upset and angry at a certain point there is nothing you can do except wait for these chemicals to dilute themselves. There are even physical correlates, such as a heart that speeds up and a face that gets red. This goes to show these scholars that many things we think of as nonphysical might in fact be simply another layer of material reality. How do these studies influence ethics? “According to sociobiologists, human social behavior, like that of other social animals, is primarily oriented toward the propagation of the species. This goal is achieved through inborn cooperative behavior that sociobiologists call biological altruism. Biological altruism accounts for the great sacrifices we are willing to make to help those who share our genes; however, sociobiologists do not equate natural with moral. Wilson writes that we as humans ‘must consciously choose among the alternative emotional guides we have inherited’” (Boss, p. 22.) In this case, ethics is simply related to our need to survive and live together. There is no higher or more profound reason for the existence of moral codes. “One of the problems with basing ethics on metaphysical materialism is that it gives us no guidance in a situation where two epigenetic rules [innate patterns that guide the behavior and thought of humans and other animals], such as egoism and altruism, are in conflict. For this and other reasons, the majority of philosophers, without denying that biology is important, reject biology as the basis for morality” (Boss, p. 22.) Sometimes this materialism is attacked for being involved in what is called “reductionism.” This means reducing things to their 12 lowest common denominator. This way of viewing the world, it is argued, does not do justice to the complexity of human life. Perhaps some day there will be more empirical evidence demonstrating what sociobiologists are studying, but in the meantime it is still only one theory among some other important ones. Thankfully, if you don’t want to be a dualist you are not yet limited to being a materialist. There are other choices! Buddhism and the Unity of All Reality Some of the most profound ideas about unity and oneness come from the world of Eastern philosophy, although it can also be found in the more mystical and esoteric schools of Western religion and philosophy as well. One example comes from Buddhism. “Buddha rejected metaphysical dualism, emphasizing the unity of all reality rather than differences. According to Buddha, the natural order is not rigidly hierarchical; rather, it is a dynamic web of interactions that condition or influence, instead of determining, our actions. Mind and body are not separate substances but are a manifestation of one substance that is referred to in most Buddhist philosophies as the ‘One.’ Because all reality is interconnected, Buddhism opposes the taking of life and encourages a simple lifestyle in harmony with and respectful of other humans and of nature in general” (Boss, p. 22.) This view of the world seems to teach that underneath the mind-body problem, underneath dualism, is a more profound reality that manifests as either physical or mental reality. So while things seem separate on the surface, a deeper look reveals how much they are the same. One way of getting your mind around these ideas is to think of metaphors. One I like asks us to picture how all of the diverse reality that we see around us shares in the same basic atomic structure. You break humans, trees, and rocks down to their smallest level and you find atoms. And what are atoms except energy? Energy, then, seems like the modern way of understanding this “one” reality that can then manifest as either physical reality or consciousness, that elusive “mind-stuff.” Many of the traditional tribal peoples of the world share a similar philosophical vision of reality. “Like most Buddhists, the Lele, a Bantu-speaking tribe living in the Democratic Republic of Congo, also believe that the world is a single system of interrelationships among humans, animals, and spirits. Avoiding behavior such as sorcery that disrupts this delicate balance of interrelationships is key to the moral life. Some Native American philosophies also stress the interrelatedness of all beings; they do not divide the world into animate and inanimate objects but rather they see everything, including the earth itself, as having a self-conscious life. This metaphysical view of reality is reflected in a moral philosophy based on respect for all beings and on not taking more than one needs” (Boss, p. 22.) This is a good example of how our view of the world influences our ethical behavior. We passed laws against cruelty to animals once we accepted their suffering as real. We don’t feel bad for a soccer ball getting kicked around because we don’t think the ball minds! But we would be outraged to see someone kick their dog around because we think a dog has feelings. This is an example of how our circle 13 of compassion gets larger as we grow wiser and more in tune with the suffering of others rather than just our own suffering, or just our family’s, or just our country’s. A child is only concerned with itself. Then as he or she matures they start to care about the people in their family and then their friends. This circle widens to include the larger community and often one’s own country. But it often stops there. However, we live in a time when this circle of concern seems to be expanding to include the whole world and even other species. Thankfully this is happening just in time as if we continued down the road of only caring about ourselves we would probably end up destroying our planet. As a result there is a whole new field of ethical concern scholars are addressing that has to do with ecological ethics. Determinism Versus Free Will Probably the biggest metaphysical barrier to being able to embrace responsibility and an ethical life, the pursuit of the good, is what I referred to above as the problem of determining whether humans are free or not. “The theory of determinism states that all events are governed by causal laws. There is no free will. Humans are governed by causal laws just as all other physical objects and beings are. According to strict determinism, if we had complete knowledge, we could predict future events with 100 percent certainty. The emphasis on the scientific method as the source of truth has contributed to the trend in the West to describe human behavior in purely scientific terms” (Boss, pp. 22-23.) We discussed this theory before under the heading of materialism. But there is a little more to think about here that comes from the current studies of human thinking and emotions. We know our bodies are governed by nature, but for a long time humans felt that they were free “on the inside.” That is, we experience our freedom in our ability to think and make choices. But even this is questioned today. “Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) claimed that humans are governed by powerful unconscious forces and that even our most noble accomplishments are the result of prior events and instincts. Behaviorists such as John Watson (1878-1958) and B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) also believed that human behavior is determined by past events in our lives. They argued that, rather than the unconscious controlling our actions, so-called mental states are really a function of the physical body. Rather than being free, autonomous agents, we are the products of past conditioning, elaborately programmed computers - according to Watson, an assembled organic machine ready to run” (Boss, p. 23.) If you have ever studied psychology then you know that much of this is true. All sorts of impulses and motivations that often don’t even enter our awareness drive us. But determinism is not the only conclusion we can come to. While acknowledging that there are many forces that drive us, some psychologists and philosophers feel that freedom is at the core of human 14 experience and reality, but that it is something we need to grow into or claim for ourselves as part of the maturing process. “According to [existentialist philosophers], we are defined only by our freedom. Existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) argued that ‘there is no human nature, since there is no God to conceive it…Man [therefore] is condemned to be free.’ He argued that, as radically free beings, we each have the responsibility to create our own essence, including choosing the moral principles upon which we act. Because we are free and not restricted by a fixed essence, when we make a moral choice, we can be held completely accountable for our actions and choices” (Boss, p. 23.) This philosophy plays into a very basic intuition that we are free. It then builds a case despite all of the determining principles that it acknowledges influence our lives. Eastern philosophy also recognizes the power of forces that are beyond our control but it does not settle for a picture of reality that makes everything fixed. “Buddhist philosophers also disagree with determinism, although they acknowledge that we are influenced by outside circumstances beyond our control. This is reflected in the concept of karma in Eastern philosophy. Karma is sometimes misinterpreted as determinism. However, karma is an ethical principle or universal force that holds each of us responsible for our actions and the consequences of our actions, not only in this lifetime but in subsequent lifetimes. Rather than our being predetermined by our past karma, karma provides guidance toward liberation from our past harmful actions and illusions and toward moral perfection” (Boss, p. 23.) Karma claims we are responsible for our choices and this implies freedom. The resistance to determinism stems from the fact that if we don’t take responsibility for our actions then we end up making up excuses for our behavior. Determinism and Excuses We live in a time of excuses. When people do something wrong they will often say they couldn’t help themselves because they were abused as children, or they are alcoholic, or for some other reason. There may even be quite a bit of truth in these insights, but it also makes it difficult for many people to take responsibility for their behavior. “The scientific trend toward seeing forces outside our control as responsible for our actions has recently been extended to relabeling behavior such as alcoholism and pedophilia as illnesses or disabilities rather than moral weaknesses. The belief that human behavior is determined has also influenced how we treat people who commit crimes. In his book The Abuse Excuse, criminal defense attorney Alan Dershowitz examined dozens of excuses that lawyers have used successfully in court to enable people to ‘get away with murder.’ More and more people, he writes, are saying ‘I couldn’t help myself’ to avoid taking responsibility for their actions. Excuses such as ‘battered woman syndrome,’ ‘Super Bowl Sunday syndrome,’ ‘adopted child syndrome,’ ‘black rage syndrome,’ ‘the Twinkies defense,’ and ‘pornography made me do it syndrome’ have all been used in court cases” (Boss, p. 24.) The emphasis here needs to be on the fact that these excuses have been used successfully! Our laws have often 15 recognized different levels of responsibility. Just think of the difference between first-degree murder and manslaughter. The question in an ethics course is can we extend different levels of responsibility all the way to no responsibility? Is a person never responsible for their actions? “At one extreme, the existentialists claim that we are completely responsible and that there are no excuses. At the other extreme are those, such as the behaviorists, who say that free will is an illusion. Most philosophers accept a position somewhere in the middle, arguing that although we are the products of our biology and our culture, we are also creators of our culture and our destiny” (Boss, p. 24.) This middle way makes the most sense to me personally. I find that as I have grown in my own life that I am freer today than I was ten years ago. Other people I have discussed this with say the same thing. In other words, freedom seems to be more of a possibility than a given fact. Freedom is a human potential. We grow up conditioned, but we can expand our horizons and find more freedom. I think of children who are brought up by racist parents. Naturally they are racist too. But as they are able to start looking around and thinking for themselves they are able to reevaluate these attitudes they were indoctrinated with before the age of reason and thus set themselves free. This whole issue of freedom versus determination will be with us throughout this course. We each have to come to our own conclusions about this difficult subject. For now, I want to move on and discuss the nature of moral knowledge. Moral Knowledge: Can Moral Beliefs Be True? How do we know what is good? Some things seem obvious, but other things are not so clear. We may even have people in our lives who are intelligent and thoughtful and whom we respect who come down on opposite sides regarding moral issues. Does this lack of agreement mean there is no moral truth? This will be another of the important questions we will be engaging throughout this course. “Disagreement or uncertainty does not negate the existence of moral knowledge. We also disagree about empirical facts, such as the age of our planet, the cause of Alzheimer’s disease, whether people in comas can feel pain, and whether it is going to rain on the weekend. When we disagree about an important moral issue, we don’t generally shrug off the disagreement as a matter of personal opinion. Instead, we try to come up with good reasons for accepting a particular position or course of action. We also expect others to be able to back up their positions or explain their actions. In other words, most people believe that moral knowledge is possible and that it can help us in making decisions about moral issues” (Boss, p. 27.) A large part of an ethics course is exactly this process of learning the process of moral reasoning. While untrained people often don’t have an understanding of how moral reasoning works, it is nevertheless a sign of our humanity that we all seem to have basic moral intuitions. “Even the most egoistic people generally accept a sort of moral minimalism. That is, they believe that there are certain minimal 16 morality requirements that include, for example, refraining from torturing and murdering innocent, helpless people. The one exception to this is psychopaths” (Boss, p. 27.) So when we think about moral knowledge, we must keep in mind that one of the main ways we gauge mental health is whether these basic insights and intuitions are present or not. Disagreements may abound, but that is not the same thing as saying there is no possibility of moral knowledge at all. That is too extreme a view. One might even argue that it is a dangerous view. Epistemology and Sources of Knowledge There is a whole field of both psychology and philosophy that studies the question of how we can know anything at all. “The branch of philosophy concerned with the study of knowledge - including moral knowledge - is known as epistemology. Epistemology deals with questions about the nature and limits of knowledge and how knowledge can be validated. There are many ways of knowing. Intuition, reason, feeling, and experience are all potential sources of knowledge” (Boss, p. 27.) The usual problem that confronts many people is the assumption that there is only one basic way of knowing. When that way does not lead to the knowledge they are seeking, they assume that it is unknowable. So we expand our consciousness right from the beginning when we acknowledge that there are many ways to learn. In the modern Western world there tends to be a bias toward reason and rationality. “Many Western philosophers believe that reason is the primary source of moral knowledge. Reason can be defined as ‘the power of understanding the connection between the general and the particular.’ Rationalism is the epistemological theory that most human knowledge comes through reason rather than through the physical senses” (Boss, p. 27.) There is no argument that reason is of critical importance. In fact, we can hope that more people become more rational as soon as possible! We need good, clear, critical thinkers to tackle the problems of the modern world. Nevertheless, all of the disagreements between very smart people should help us be cautious about giving reason and rationality too much power. Perhaps reason is not our only guide, especially concerning something as close to our hearts and lives as morality and the search for the good. “Other Western philosophers, such as Bentham, Ross, and Hume, and many non-Western philosophers, including Confucius and Buddha, have challenged the dependence on reason that characterizes much of Western philosophy. They suggest that we discover moral truths primarily through intuition rather than reason. Intuition is immediate or self-evident knowledge, as opposed to knowledge inferred from other truths. Intuitive truths do not need any proof. Utilitarians, for example, claim that we intuitively know that pain is a moral evil. Confucians maintain that we intuitively know that benevolence is good. Rights ethicists claim that we intuitively know that all people are created equal” (Boss, p. 27.) Even the United States Declaration of Independence talks about truths that we consider “self- 17 evident.” What does that term “self-evident” mean? It means it is obvious to both the light of human reason, but also to our gut level instincts. Perhaps we know on some deep level that it is wrong to hurt others because it engages our feelings. We are able to empathize because we know how it feels to be hurt by others and we know that we not only don’t like it, but that there is something inherently wrong about it. One of the things scholars study about humanity is the nature of these “selfevident” truths. Are they like instincts? “Cognitive-developmental psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg believes that certain morally relevant concepts, such as altruism and cooperation, are built into us (or at least almost all of us). According to Kohlberg, these intuitive notions are part of humans’ fundamental structure for interpreting the social world, and as such, they may not be fully articulated. In other words, we may know what is right but not be able to explain why it is right” (Boss, p. 28.) This is why people who we look up to as persons who embody the good life may become confused when we ask them to explain why they choose to live the way they do. It just seems so obvious to them that it is the right way that they might not have taken the time to explain it to themselves. Can we rely on intuition then, instead of reason? Why bother explaining about the good anyway? “The difficulty with using intuition as a source of moral knowledge is that these so-called intuitive truths are not self-evident to everyone. White supremacists, for example, do not agree that all people are created equal. On the other hand, the fact that some people do not accept certain moral intuitions does not make these moral intuitions false or nonexistent any more than the deafness of some people means that Beethoven’s symphonies do not exist” (Boss, p. 28.) We don’t exist alone in the world. We must live with others and when we disagree we must have a way of discussing the issues. Therefore we need a way of approaching moral knowledge that allows this dialogue to take place. Because so many people receive their basic moral grounding through early religious training, this religious language might be a key to the dialogue. The problem here is that we live in a society of people from many different religions and with a growing population of people who have no religious beliefs at all. “Since knowledge gained by faith is not objectively verifiable, we have no criteria for judging the morality of the actions of someone who, for example, commits an act of terrorism in the name of their faith. Most religious ethicists, such as Thomas Aquinas, overcome this problem by grounding morality not in faith but in objective and universally applicable moral principles based on reason” (Boss, p. 28.) A person might say they believe that something is wrong because the Bible says so. But this will only hold validity for other people who believe that the Bible is a valid source of insight. What if you are trying to convince someone who does not believe this? Then you can’t appeal to something like the Bible that you don’t hold in common, but something you do hold in common such as reason and feelings. 18 The Role of Experience Not only reason and intuition guide us in forming our ideas about the nature of the good, but also we gain powerful insights from our growing experience of life. “Aristotle emphasized reason as the most important source of moral knowledge, yet he also taught that ethics education needs an experiential component to lead to genuine knowledge. Some philosophers carry the experiential component of moral knowledge even further. Empiricism claims that all, or at least most, human knowledge comes through the five senses” (Boss, p. 28.) I think one reason for moral confusion today is that our experience of life has grown a great deal. We now not only have access to our own culture and religion and family but to virtually all cultures and religions, in the present and in the past. This gives us a great deal more information and insight into different understandings about what is good. Earlier we discussed materialism. Those who lean in this direction look to science and the scientific method, such as empiricism, to help us find our way through the moral confusions that beset us. “Positivism, which was popular in the first half of the twentieth century, represents an attempt to justify the study of philosophy by aligning it with science. Positivists believe that moral judgments are simply expressions of individuals’ emotions; this is known as emotivism. Because statements of moral judgment don’t seem to convey any information about the physical world, they are meaningless. Emotivists such as Alfred J. Ayer (1910-1989) concluded that these moral judgments are merely subjective expressions of feeling or commands to arouse feelings and stimulate action and, as such, are devoid of any truth value” (Boss, pp. 28-29.) In other words, morality is not something that can be proved through reason at all. Rather it comes from our feelings, which because they are subjective do not approach the objectivity that is often sought for in scientific circles. But as we saw above with materialism, there are real difficulties here if this becomes the exclusive way of trying to do ethics. “This alliance between ethics and science (as interpreted by the positivists) proved fatal to ethics. If science is the only source of valid knowledge, then moral statements such as ‘killing unarmed people is wrong’ and ‘torturing children is wrong’ are meaningless because they do not appear to correspond to anything in the physical world, as do statements such as ‘tigers have stripes’ or ‘it was sunny at the beach yesterday’” (Boss, p. 30.) The problem is that it is too subjective. Is something right only because it feels right to me? If this is true then how do we have a nation, let alone a world, of laws that we can hold people accountable to? What if they disagree? How can we tell someone that their cruel treatment of children or animals is wrong if there is no objective standard? These are some of the difficult problems we have to face with ethical theories such as emotivism and positivism. “Emotivism was never widely accepted as a moral theory. The horrors of the suffering wrought by the Holocaust forced some emotivists to reevaluate their 19 moral theory and to commit themselves to the position that some actions are immoral: Genocide, like torturing children, is wrong - regardless of how one feels about it” (Boss, p. 30.) But while it may not suffice to undergird ethics entirely, we will see that emotions still play a critical role in our discernment of what is right and what is wrong. For example, “Philosopher Sandra Harding (b. 1935) also maintains that experience is an important component of knowledge; however, she disagrees with the emotivists that moral knowledge is impossible. Moral knowledge, she claims, is radically interdependent with our interests, our cultural institutions, our relationships, and our life experiences such as those based on gender and social status. To rely solely on abstract reasoning, she argues, ignores other ways of experiencing the world and moral values within the world. Instead, knowing cannot be separated from our position in society and from other practical pursuits such as working toward greater justice and equality. Moral knowledge and moral decision making lie within the tension between the universal and the particular in our individual experiences. By emphasizing the importance of experience, feminist epistemology reminds us that we must listen to everyone’s voice before forming an adequate moral theory - not just the voice of those, such as ‘privileged White males.’ This concern with experience has led to an increased emphasis on multiculturalism in contemporary college education” (Boss, p. 30.) This is a reminder that we gain a great deal of our moral knowledge from our experience of being active in the world. For example, many of us start to build a social consciousness when we are required by our families and schools to do community service work. This exposes us to suffering and problems and we start to care and want to do something to eliminate some of the pain people experience. This has an enormous impact on our ethical life. Reading about poverty is a very different experience from actually seeing it for yourself. We have covered a lot of ground! We have discussed the definition of ethics as the study of right and wrong. We spent a good deal of time discussing relativistic and universalist theories about ethics and the problems associated with each. We spent a lot of time describing the importance of psychology in understanding ethics in terms of the free will and determinism argument. In the next lecture we will explore how experience, interpretation, and analysis work and build on one another. We will study this in an integral framework that includes moral sensitivity, ontological shock, and praxis as necessary conditions for a true ethics to be studied and put into practice. We also study the basics of moral reasoning. Until next time I wish you well! Bibliography: Judith A. Boss, Ethics For Life: A Text With Readings, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2008] 20 Donald Palmer, Looking at Philosophy: The Unbearable Heaviness of Philosophy Made Lighter, Fourth Edition, [New York, New York: McGraw Hill, 2006] Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, [New York, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945] Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View, [New York, New York: Harmony Books, 1991] Bruce Waller, You Decide! Current Debates in Contemporary Moral Problems, [New York, New York: Pearson, 2006] 21