The Sand Creek Massacre

advertisement

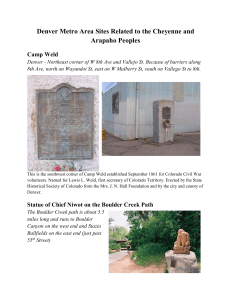

The Sand Creek Massacre On November 29, 1864 700 soldiers of the Colorado Cavalry killed 133-200 unarmed Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian people who were camped peacefully at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. Originally called “the Battle of Sand Creek,” the name of the incident was changed to “the Sand Creek Massacre” after a Congressional investigation determined that this had been a massacre (defined as “the intentional killing of a considerable number of human beings, under circumstances of atrocity or cruelty”). The Sand Creek Massacre was the result of a number of factors that converged at a particular historical moment: the influx of increasing European immigrants into Colorado territory and subsequent pressure to remove Native Americans from this land; miscommunication; corrupt Indian agents; fear; Territorial Governor John Evans’ political ambitions; and Colonel John Chivington’s desire to be elected to the United States Congress and his hatred for Native people. In the 1850s and 1860s increasing numbers of gold miners moved into Colorado territory, leading to numerous clashes between Euroamerican settlers and Native American tribes, often with Natives attacking wagon trains and mining camps as their lands were invaded. By the terms of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the United States and seven Indian nations, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were recognized to hold a vast territory encompassing an area that included present-day southeastern Wyoming, southwestern Nebraska, most of eastern Colorado, and the westernmost portions of Kansas. In November 1858, however, the discovery of gold in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado led to the Pikes Peak Gold Rush and a consequent flood of white migration across Cheyenne and Arapaho lands. Colorado territorial officials pressured federal authorities to redefine the extent of Indian lands in the territory, and in the fall of 1860, a new treaty was negotiated in which a much smaller portion of land in eastern Colorado was allocated to the tribes. The tribes were split over the decision to sign the treaty, and some Cheyennes who opposed the treaty claimed that it had been signed by a small minority of the chiefs without the consent of the rest of the tribe. These Cheyennes argued that those who signed the treaty had not understood its terms, and that they had been bribed into signing by the promise of gifts. The government, however, argued that those Indians who refused to abide by the treaty were hostile and would wage a war against white settlers. Colorado Governor John Evans sought to open up Cheyenne and Arapaho hunting grounds to white development. In the face of tribal resistance, Evans called on volunteer militiamen under Colonel John Chivington to quell the mounting violence. Evans used isolated violent incidents as a pretext to order troops into the area and fueled reports in the media of Indian hostility and menace. Evans worked closely with the ambitious, Indian-hating military commander Colonel Chivington. Though John Chivington had once belonged to the clergy, be maintained a deep-seated hatred of Indians, at one point stating, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! . . . I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God's heaven to kill Indians.” In the spring of 1864, Chivington launched a campaign of violence against the Cheyenne and their allies. The Cheyenne, joined by neighboring Arapahos, Sioux, Comanches, and Kiowas in both Colorado and Kansas, went on the defensive. Evans and Chivington reinforced their militia, forming the Third Colorado Calvary of short-term volunteers. After a summer of scattered raids and clashes, white and Indian representatives met at Camp Weld outside of Denver. No treaties were signed, but the Indians believed that by camping near army posts, they would be declaring peace and accepting sanctuary. Black Kettle was a peaceful chief of a band of 600 Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos who followed the buffalo along the Arkansas River of Colorado and Kansas. They reported to Fort Lyon and then camped on Sand Creek about 40 miles north. Shortly afterward, Chivington led a force of about 700 men into Fort Lyon. Although he was informed that Black Kettle had already surrendered, Chivington pressed on with what he considered a prime opportunity to further the cause for Indian extinction. On the morning of November 29, he led his troops, many of them drinking heavily, to the Sand Creek Indian village. Black Kettle raised both an American and a white flag of peace over his tepee. Yet the Indian men, women, and children were hunted down and shot over a period of seven hours on November 29. A few warriors managed to fight back to allow some of the tribes to escape, including Black Kettle. Chivington and his men dressed their weapons, hats and gear with scalps and other body parts, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia. They also publicly displayed these battle trophies in Denver area saloons. By the end of the massacre, between 133-200 Indians, more than half women and children, had been killed and mutilated. One witness reported to Congress: I saw the bodies of those lying there cut all to pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before; the women cut all to pieces ... With knives; scalped; their brains knocked out; children two or three months old; all ages lying there, from sucking infants up to warriors ... By whom were they mutilated? By the United States troops. (John Smith) While the Sand Creek Massacre outraged Americans in the east, it seemed to please many people in Colorado Territory. Chivington later appeared on a Denver stage where he was celebrated for his war stories and where he displayed 100 Indian scalps. When asked at a congressional investigation why children had been killed, one of the soldiers quoted Chivington as saying, “Nits Make Lice.” Chivington was later denounced by Congress and forced to resign from his post. Even still, a Civil War memorial installed at the Colorado Capitol in 1909 listed the Sand Creek massacre as one of the Union's great victories and a stone marker at the site of the massacre commemorated the “Sand Creek Battle Ground.” The site is now preserved by the National Park Service and was renamed the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2007, almost 142 years after the massacre. In the aftermath of the massacre, Cheyenne and Arapaho people today continue their efforts to be paid by the United States government according to the terms of their treaty. The government has not fulfilled obligations outlined in the treaty to provide legal representation, land patents, and other resources, and is prolonging the lawsuits without being proactive. Meanwhile, the government continues to support activities such as natural gas and oil development, ranching, and timber harvesting on tribal land, with profits going primarily to private industries. In return, the tribes have endured disease, poverty, hunger, alcohol and drug abuse, high unemployment, and inadequate housing and health care. The Sand Creek Massacre remains an unresolved, open wound for Cheyenne and Arapaho people, a tragedy that has yet to be officially acknowledged by mainstream American society.