Huntington`s disease: The Care of Patients and their Family in Ireland

advertisement

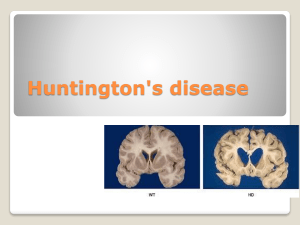

Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 Huntington’s Disease: The Care of Patients and their Family in Ireland Dr Niall Pender, BA, MSc, MSc, Dip, PhD, CPsychol, RegPsychol PSsI, AFBPsS, FPsSI Principal Clinical Neuropsychologist, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin Executive Summary: Huntington’s disease an inherited, progressive, degenerative brain disease. There is currently no cure for Huntington’s disease. In Ireland, at present, there are approximately 700 families affected by the disease who have no access to specialist services. The neurological consequences of HD make those affected extremely vulnerable. Behavioural and psychiatric changes lead to fracturing of normal family supports and those affected are at increased risk of serious injury, homelessness, suicide, drug and alcohol misuse and exploitation What is urgently required is an integrated network of specialist multidisciplinary clinics across Dublin, Cork and Galway, to support this highly vulnerable and neglected cohort of people. Such clinics will not only enable patients to obtain responsive and specialist treatments but also facilitate enrollment in clinical trials thereby enabling them to benefit from new and exciting treatments. However, at present in Ireland we have no such dedicated specialist teams. This results in patients having to struggle with the direct and indirect consequences of the disease and miss out on appropriate treatments and care as the disease inevitably deteriorates. The Huntington’s Disease Association of Ireland works tirelessly with negligible funding to support families in crisis and provide care to patients with this devastating disease but they too require more support and assistance to carry out their excellent work. 1. Overview: Huntington’s disease (HD) is an inherited, slowly progressing brain disease that results in severe dementia, a crippling movement disorder and psychiatric difficulties resulting in 24-hour care, and eventual death over 20 years. 1 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 HD known as an autosomal dominant (inherited) neurodegenerative brain disorder. The genetic mutation was identified in 1993. There is no known treatment to slow or cure the pace of neurodegeneration which generally leads to death over a 20-year period after clinical diagnosis. The clinical manifestations of the disease vary widely but they generally include dysfunction in cognition, mood, voluntary motor control and most patients have the signature finding of chorea. There is currently no dedicated treatment team for patients with HD in Ireland. 2. Introduction: From a technical perspective, HD results from an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat (Cytosine Adenine Guanine; CAG) causing an expanded polyglutamine chain in the huntingtin gene located on chromosome 4p16.3 (Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group, 1993; Sutherland & Richards, 1993). CAG repeat lengths lower than 26 are considered stable and result in no clinical symptoms or known increased risk to future generations (Potter et al., 2004). Repeats of 27 - 35 CAG are considered intermediate, and symptoms are not expected to manifest in these individuals but can lead to greater expansions with morbidity in future generations (Potter et al., 2004). Their symptomatic offspring, however, have mutations with longer repeat lengths. Repeat lengths of 36 – 39 CAG repeats have reduced penetrance, with most individuals becoming symptomatic, but often with a milder expression in midlife. CAG repeat lengths over 39 will result in symptomatic HD. In adults, the length of the CAG repeat expansion accounts for up to 70% of the variability relative to age of onset (Vittori et al. 2014). While there is no unique set of symptoms which indicate the onset in HD, many patients present initially with symptoms that reflect early neurological impairment, such as brief random irregular muscle jerks (chorea), writhing movements (athetosis), difficulty walking and a tendency to fall or clumsiness. Many also present with a range of psychiatric problems including depression and anxiety. The rate of suicide in patients with HD is higher than normal base rates and accounts for 7% of deaths in non-hospitalised HD patients and 1.8%-5.3% among individuals at 50% risk. (Wetzel et al, 2011; Hubers et al. 2012). There are also reports of selfinjury, alcohol abuse, criminal offences and marital difficulties. 2 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 Cognitive impairments such as poor short-term memory, poor concentration, deterioration in work performance, and poor judgement have been noted in the early stages. Recent research has identified that HD patients have emerging difficulty with aspects of social interaction before movements become apparent which results in poor inter-personal relationships. As a result of degeneration in the brain regions dealing with personality and behaviour, patients can become aggressive or violent as the disease progresses. 3. Clinical Course HD is rare and the course of the disease can be variable. The average age of motor onset is around 42 years but HD can begin in childhood (Juvenile HD; Douglas et al, 2013) or even in the elderly. Juvenile onset (onset before 20 years of age) occurs in about 5%-15% of HD cases worldwide (Potter et al., 2004). It has been estimated that over 25% of cases begin after the age of 50 years whereas 7% begin before 20 years of age. The disease has almost equal prevalence in males and females but a marked variability in the age of onset both within and between families has been noted. As the mutation is present from birth and the condition is slowly progressive, the precise onset of disease may be difficult to identify. By convention the disorder is usually diagnosed when chorea (a rapid twitching muscle jerking) manifests. However, most patients have changes that predate their movements, which are frequently detected by close family members, some of whom have witnessed similar changes in the parent or siblings. The early changes may be in behaviour, memory, mood, speech pattern, facial expression, or gait and posture. Reduced job performance and marital discord can lead to major upheaval in those who have inherited the mutation but do not yet have chorea. The individual with early signs of HD has grown up in a family in which one of the parents became affected and the parent may have passed through the course of the disease and died The psychological stress in such persons is difficult to underestimate. They, and their siblings, have been dreading the 50/50 chance that they will become affected. A fall or stumble can precipitate a fear that the disease has come. In the disease prodromal phase, depression can develop years before the onset of motor 3 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 symptoms, and the highest prevalence has been reported within 1 year of clinical diagnosis (Epping & Paulsen, 2011). 4. Prevalence In the general population of the western hemisphere, the prevalence rate of HD is estimated to be 4-10 per 100,000. There is large variance in prevalence ratings, though a 20-year retrospective analysis of records in the UK recently revealed the prevalence rate has risen from 5.4 per 100,000 in 1990 to 12.3 per 100,000 in 2010, (Tabrizi et al. 2009; Evans et al. 2013), consistent with dementia prevalence as recently outlined in the National Dementia Strategy (Department of Health, 2014) . A higher prevalence has been reported in South Wales and Venezuela as compared to a lower rate found in Finland, Japan and African-American populations. 5. Symptomatology Huntington’s disease is associated with a triad of difficulties including the movement disorder as well as cognitive and neuropsychiatric conditions. Each of these is associated with a complex set of psycho-social problems. Patients with Huntington’s disease face a range of difficulties from diagnosis to death and these difficulties are not confined to the patient themselves but also to the family. 6. Family and Psychosocial features: There are, understandably, significant family stressors and there are marked difficulties for both affected and unaffected siblings. Unaffected parents suffer the difficulties of caring for spouses and affected children with economic and psychological difficulties. A recent investigation by Banaszkiewicz et al., (2012) into caregiver burden found that motor impairment and symptoms of depression were the most important factors predicting caregiver burden. Significant support is needed for HD families from the multi-disciplinary team, with specifically tailored psychological interventions available. 7. Care and disability management of the person with the HD There is no current cure for Huntington’s disease. Chorea will respond to medication though it is important to check whether the drugs are associated with better overall motor function due to the side effects. Speech, language and swallowing therapy may 4 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 help teach safe swallowing. Physical activity to maintain muscle tone may be helpful. Often the environment needs to be modified. Padding wheelchairs and bed rails to avoid trauma from the chorea may be critically important. Abnormal movements may be so severe that the patient is not safe in a bed and better cared for on a large mattress that rests on the floor. Use of restraints can be dangerous as combined with the choric movements the restraint ties can lead to significant harm, even strangulation. Feeding the person with advanced HD is also challenging. Oral feedings need to be changed over time to a softer but thick consistency. Early-on thin liquids like water and dry crumbly foods cause cough and aspiration. Then solid foods are too difficult to chew and swallow. One characteristic of persons with HD is that they tend to over stuff the mouth as their swallowing efficiency decreases and swallowing takes more and more time. Caregivers may continue oral feeding into the late stages with pureed foods but feeding is done very slowly over long time periods. Weight management is important as patients with HD tend to deteriorate with weight loss and in some cases have improved with weight gain. The decision to insert a feeding tube is especially difficult and needs to be discussed with the patient or family years before the decision is anticipated. Otherwise the patient may be unable to communicate when the feeding crisis occurs. In general patients with HD die of aspiration pneumonia so a feeding tube can prolong life for those who are very severely disabled. 8. Appropriate standards of Care for patients with HD The standard of care for patients with HD will vary depending on their stage of the disease, whether it is pre-manifest, genetic testing, early, middle or late stages. The unaffected siblings will also require input. In Ireland at the present time we have no dedicated and responsive multi-disciplinary service for patients with HD. Such patients require complex interventions delivered by a range of professionals that must be flexible their needs and the stages of their disease. Dr Timothy Counihan, consultant neurologist in Galway, has a specialist interest in HD and following discussion with Dr Counihan we would suggest that such a team should consist of the following: 5 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. i. j. Neurologist/ Psychiatrist; Neuropsychologist; Social Worker; Speech/Language Therapist; Movement Disorder Nurse Specialist; Probably a genetic counselor; Dietitian; Physiotherapist; Occupational Therapist; Representative from the HDAI. 8.1 Proposed Solution: In order to ensure that services to patients with HD in Ireland meet the international requirements we would recommend that three regional HD Clinics (Dublin Cork and Galway) be established with sufficient resources to staff them. This will ensure that all patients in Ireland have access to specialist and flexible clinical services. In Beaumont Hospital we are running a HD behavioural/cognitive clinic and in doing so trying to put patients in touch with appropriate local services, provide emotional/psychological support to patients and their families, and evaluate cognitive/behavioural difficulties. This is being done from limited existing resources re-allocated to this group with no additional service provision. But this is falling far short of the required services for this vulnerable group who need the services of a full multi-professional team to address their needs and maintain their function. There is considerable evidence for the benefit of such teams in other complex neurological events. For example, model exists in the MND clinic in Beaumont Hospital run by Prof Orla Hardiman, which has shown significant benefits for patients’ health, well-being and life-expectancy. Such clinics can maximise functional independence, maintain employment for longer and minimise un-necessary attendance at Hospital Emergency Departments. They can treat emerging difficulties quickly and in a timely manner before they become problematic and reduce the need for emergency and inappropriate hospital admissions. Developing a relationship with a clinical team can help family members adjust and cope with the disease burden and identify other family members with emerging symptoms thereby enabling the development of appropriate early care plans. The team can also help patients and their families prepare for later stage high dependency care and end of life decisions. 6 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 HD patients and their families have struggled for many years to cope and need services that meet their considerable physical, emotional, medical, and functional needs. Many families have to fight extensively for even the most basic of interventions and this is unnecessary in the 21st Century. 9. Research Research into rare diseases such as HD is complex due to the small numbers and sourcing funding for the research programmes. International collaborations exist to facilitate such research and Ireland has, until recently, been unable to join such programmes. However, in Beaumont Hospital we have recently been able to join the large-scale international collaboration known as the ENROLL-HD to gather observational data on HD patients over time to facilitate treatment trials. However, further support is required for all research teams to enable Irish researchers to contribute at an international level to the care of HD patients. 10. Conclusions: Huntington’s disease affects approximately 700 people in Ireland directly and countless more indirectly. It is a relentless devastating deteriorating brain disease. These patients and their families carry a huge burden in dealing with the range of symptoms and their impact on day-to-day functioning. There are good models of care for such patients but we are not providing these in Ireland for such a vulnerable population. If services are to be put in place for such patients it will have an enormous impact of quality of life, survival and functional ability and also enable patients and their families to remain more active and functional for longer. References: Banaszkiewicz, K., Sitek, E.J., Rudzińska, M., Soltan W., Slawek, J. et al. (2012). Huntingotn’s disease from the patient, caregiver and physician’s perspective: three sides of the same coin? J Neural Transm, 119, 1361-1365. Burke, T, Doherty, CD, Koroshetz, W., & Pender, N (In Press). Huntington’s disease. In Orla Hardiman and Colin Doherty (Eds). Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Clinical Guide (2nd Edition). Department of Health. Report of the Minister for Health on the Irish National Dementia Strategy. December 2014 7 Dr Niall Pender, Huntington’s disease January 2015 Douglas, I., Evans, S., Rawlins, M.D., Smeeth, L., Tabrizi, S.J., & Wexler, N.S. (2013). Juvenile Huntington’s disease: a population-based study using the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open, 3, e002085. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012002085 Epping, E.A. & Paulsen, J.S. (2011). Depression in the early stages of Huntington disease. Neurodegen. Dis. Manage, 1(5), 407-414 Evans, S.J.W., Douglas, I., Rawlings, M.D., Wexler, N.S., Tabrizi, S.J., et al. (2013).Prevalence of adult Huntington’s disease in the UK based on diagnoses recorded in general practice records. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 84, 1156-1160 Hubers, A,AM., Reedeker, N., Giltay, E.J., Roos, R.A.C., Van Dujin, E. et al. (2012). Suicidality in Huntington’s disease. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 550-557. Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group (1993). A Novel Gene Containing a Trinucleotide Repeat That Is Expanded and Unstable on Huntington’s Disease Chromosomes. Cell, 72, 971-983. Potter, N.T., Spector, E.B. & Prior, T.W. (2004). Technical Standards and Guidelines for Huntington Disease Testing. Genetics in Medicine, 6(1), 61-65. Rooney, Byrne, Heverin, Tobin, Dick, Donaghy and Hardiman, (2014). A multidisciplinary clinic approach improves survival in ALS: a comparative study of ALS in Ireland and Northern Ireland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014 Dec 30. pii: jnnp-2014-309601. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309601. [Epub ahead of print] Sutherland, G.R. & Richards, R.I. (1993). Dynamic mutations on the move. Journal of Medical Genetics, 30, 978-981. Tabrizi SJ, Langbehn DR, Leavitt BR, et al. Biological and clinical manifestations of Huntington’s disease in the longitudinal TRACK-HD study: cross-sectional analysis of baseline data. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 791–801. Vittori, A., Breda, C., Repici, M., Orth, M., Roos, R.A. et al., (2014). Copy-number variation of the neuronal glucose transporter gene SLC2A3 and age of onset in Huntington’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 23(12), 3129-3137. Wetzel, H.H., Gehl, C.R., Dellefave-Castillo, L., Schiffman, J.F., Shannon, K.M., et al. (2011). Suicidal ideation in Huntington disease: the role of comorbidity. Psychiatry Research 188 (3), 372–376. 8