PAUL RICOEUR

advertisement

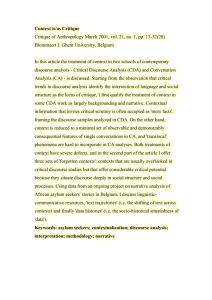

PAUL RICOEUR (1913 - ) Ricoeur is a French philosopher whose work deals with language, interpretation, subjectivity, the nature of the will, and human action. He was influenced by German phenomenology (Husserl, Heidegger, and Jaspers) and structuralism and psychoanalysis (Lévi-Strauss and Barthes [pronounced ‘Bart.’]). The core of his beliefs about language are The previous view of language, against which Ricoeur writes, is that language describes ‘what is.’ Ricoeur disagrees— Instead, he writes, “the function of language is to articulate our experience of the world—to give form to this experience.” Ricoeur views language as a discourse: a dynamic enterprise by which we communicate our experience to others and create new ways to form the world. Ricoeur creates an important opposition between speech and writing. For him, writing cannot be understood on the model of speech; it is significantly different. Writing ‘intercepts’ the relation to the world and the relation between subjectivities that exist in the situation of speech. Since language (speech) is a dynamic activity, and writing “fixes” the language, writing is fundamentally different from speech. Writing is detached from the original circumstances which produced it, the intentions of the author are distant, the addressee is general rather than specific, and ostensive references are absent. Here are some of his quotes about writing (Ricoeur, 1982): “What is a text? . . . Let us say that a text is any discourse fixed by writing.” “The book divides the act of writing and the act of reading into two sides, between which there is no communication.” “Writing preserves discourse and makes it an archive available for individual and collective memory.” “We explain the text in terms of its internal relations, its structure. On the other hand, we can lift the suspense and fulfill the text in speech, restoring it to living communication; in this case, we interpret the text . . . Reading is the dialectic of these two attitudes.” “To read is, on any hypothesis, to conjoin a new discourse to the discourse of the text.” Written words no longer “point” to a reference the way that spoken words do, but “written words become words for themselves.” Language and reality We share reality through common signs. We cannot share anyone else’s reality except through the mediation of our symbolic world—that is, through a ‘text’ of some sort, which has a context (or many contexts). When you “understand” someone, you assimilate what is said to the point that it becomes your own. It now lives in your context and symbols. Our symbolic world is not separate from our beings, especially in regard to language. We “ARE” language, in that what distinguishes us as persons is that we are beings who are conscious of themselves, that is, can know themselves symbolically and self-reflexively. Heidegger (everyone’s favorite) remarked “language speaks man.” (and wo-man, I must add.) We are not beings who ‘use’ symbols, but beings who are constituted by their use. Therefore, all experience is articulable in principle; although it is not reducible to its articulation, it is brought into being for us through its symbolic representation. Ricoeur said, “To bring [experience] into language is not to change it into something else, but, in articulating and developing it, to make it become itself” (Phenomenology and Hermeneutics). Experience is not just language; experience pre-exists language at the time language brings it into meaning. Language and self: According to Ricoeur, a person’s self derives fundamentally from their narrative location. An answer to the question “who am I?” will not come from metaphysical truth structure but, rather, from the contingencies of the stories in which the person is located. Central to Ricoeur’s notion of narrative is the idea of emplotment, a continual process of reorientation through which stories achieve and maintain intelligibility. For Ricoeur a story is not simply a chance configuration of real events thrown together arbitrarily but, rather, it is the narrative configuration itself which gives meaning to events, which confers to physical happenings the very status of “event.” Ricoeur writes, “an event must be more than just a singular occurrence. It gets its definition from its contribution to the development of the plot. A story, too, must be more than just an enumeration of events in serial order; it must organize them into an intelligible whole, of a sort such that we can always ask what is the ‘thought’ of this story. In short, emplotment is the operation that draws a configuration out of a simple succession.” The narrative unity of a life is actually an unstable mixture of fabulation and actual experience. It is precisely because of the elusive character of real life that we need the help of fiction to organize life retrospectively. GLOSSARY Discourse: according to Émile Benveniste, ‘discourse’ is language insofar as it can be interpreted with reference to the speaker, to his or her spatiotemporal location, or to other such variables that serve to specify the localized context of utterance. The study of discourse thus includes personal pronouns (especially ‘I’ and ‘you’), deictics of place (‘here,’ ‘there,’ etc.) and temporal markers (‘now,’ ‘today,’ ‘last week’), in the absence of which the speech act in question would lack determinate sense. More often, discourse signifies any piece of language longer (or more complex) than the individual sentence. Hermeneutics: The theory and methodology of interpretation, especially of scriptural text. Ricoeur is proudly known as the “father” of hermeneutics. Immanent: Existing or remaining within; inherent: believed in a God immanent in humans; restricted entirely to the mind; subjective. Post-structuralism: Emerged in the late 1970s. The idea that all perception, concepts, and truth-claims are constructed in language, along with the corresponding ‘subject-positions’ which are likewise nothing more than transient epiphenomena of cultural discourse. Language is a system of immanent relationships and differences. Structuralism: an interdisciplinary movement of thought, popular through the 1960s and early 1970s. The primary principle, derived from Saussure, is that cultural forms, belief systems, and ‘discourses’ of every kind can best be understood by analogy with language, or with the properties manifest in language when treated from a strictly synchronic standpoint that seeks to analyze its immanent structures of sound and sense.