Rev ISIH Gassendi an..

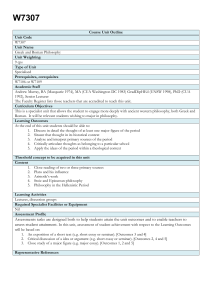

advertisement

1 Gassendi and the Void ISIH Conference April 18, 2007 Ann Orlando Slide 1 Hello; I am Ann Orlando from Weston Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is my pleasure to be here this afternoon. Today we take the reality of voids for granted, we talk easily about the vast regions of empty space. But until the seventeenth century most natural philosophers believed that no such thing existed. After all, if it was nothing, then how could it exist. Pierre Gassendi, one of the leading figures of the scientific revolution, more than anyone else challenged this, and argued convincingly that in fact vacuums are found in nature and are integral to the way in which nature ‘works.’ His arguments were based not only on new physical observations but also on the Christian tradition, a tradition which had through the previous centuries, denied the existence of a void. To elucidate these arguments, I will begin by describing Gassendi’s overall intellectual model and systematic philosophy. 2 Slide 2 Background on Pierre Gassendi Pierre Gassendi was born in Champtercier, France in 1592; he died in Paris in 1655. During his life Gassendi had three parallel careers: ecclesial, academic and intellectual. By far the most important of these was his career among the intellectual elite of France. He was a member of several correspondence groups of European intellectuals whose members included Mersenne, Galileo, Descartes, Hobbes and Pascal. Along with Gassendi, they debated new scientific theories and experiments. Although these early modern philosophers and physicists often differed with each other, they were unified in rejection of Aristotelian physics; in its place they were developing the mechanical universe model of physics. Gassendi himself made critical contributions to this development. He was recognized in his own time as a brilliant experimental physicist in astronomy, dynamics, optics and atomic theory. However there were three abiding beliefs that Gassendi held which placed him out of step with most of the natural philosophers in the his own day and succeeding generations. First, he believed that the book of nature could best be described by words, not mathematics. Second, he believed that those words were best developed considering all past words spoken on any subject. Third, he believed that physics and religion were part of one unified whole. That is, he tried to reconcile the book of nature and the book of faith. 3 Slide 3 Intellectual Model To effect that reconciliation, he relied on the techniques of both the empiricists and the humanists. But he did so from the perspective that human knowledge is uncertain; he advocated for a probabilistic epistemology that always left room for new explanations as additional data (whether empirical or humanist) became available. His physics was first and foremost based on observation and inference to the most probable result. Gassendi believed the mind was a tabula rasa on which data from the senses was projected, combined and analyzed to form understanding. But he was not a naïve empiricist. He recognized that observations and initial premises could be faulty or incomplete. Richard Popkin, for instance, has analyzed the importance of skepticism in Gassendi’s epistemology.1 For Gassendi, we can never know perfectly and must continually rely on new information from our senses to advance knowledge. Through physics and the study of nature we can at least know things approximately, or probably. Therefore, according to Gassendi, the goal of physics is “if not to pursue the truth of things, at least (to pursue) the true likeness of things.”2 Also important in Gassendi’s epistemology is the relationship between mathematics and physics. David Sepkoski observed, “Gassendi’s nominalism and mathematical constructivism thus departed from Cartesian and Galilean philosophy of mathematics by denying that mathematical objects (and similar abstractions) were ontologically real.”3 Rather, to the extent that mathematics was useful at all, it could at 1 Richard Popkin, The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza (New York: Harper Row, 1965). Gassendi, 1:132. “…nisi rerum veritatem, saltem versilmilitudinem assequi…” All references to Gassendi are from the Opera Omnia unless otherwise noted. 3 David Sepkoski, “Nominalism and constructivism in seventeenth-century mathematical philosophy,” Historia Mathematica 32 (2005): 41. 2 4 best provide a description or label for empirical observations. For Gassendi, mathematics could not ‘prove’ or demonstrate anything about nature. “When a mathematician proves some proposition you had not known, he accomplishes no more than a man who discloses the contents of a casket by writing out a label for it by opening it up.”4 In place of mathematics, Gassendi thought words were the best descriptors of nature; all words previously written on any subject in natural philosophy should be evaluated for their validity using the techniques developed by the Renaissance humanists. Lynn Sumida Joy has analyzed in detail Gassendi’s intellectual development as a humanist.5 His acceptance of revelation and the truths taught by religion are based on his willingness to accept the truth of accounts from others whom he considers authoritative. “What is accepted by all or most knowledgeable persons and by those who are all for the most part persons of distinction and status has the least grounds for being disbelieved.”6 For Gassendi the most authoritative source of knowledge was the Bible: “Consequently, Divine Faith which we have from God is the firmest since we have a preconception that God is certainly absolutely truthful.”7 He observes that although divine faith “does not possess the evidence which science acquires through demonstration, it nevertheless acquires its evidence from divine authority, which gives it a certainty equal to itself.”8 The certainty of faith depends on the authority of the speaker, and since God’s authority is absolute, faith (and only faith) can be known with certainty. However, even authoritative human opinion can only have degrees of certainty. For 4 Ibid., 3: 208, trans. Brush, 106 Lynn Sumida Joy, Gassendi the Atomist (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). 6 Gassendi, Institutio; trans. Howard Jones (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1981), 119. 7 Gassendi, 1:120. “Ex quo efficitur, ut Fides Divina, seu quam Deo habemus, firmissima sit, quia praeconcepimus Deum sic certo certuis esse veracem.” 8 Ibid., 1:121; trans. Jones, 149. 5 5 Gassendi, the humanists’ methods could suggest the degree of certainty that should be credited to human authors, just as repeated experiments could determine the degree of certainty to attach to observed data. 6 Slide 4 Toward a Systematic Philosophy Gassendi’s life project was finding the correct philosophical framework within which to organize both empirical and humanist data to create the most probable understanding on any topic in natural philosophy. He discovered in Epicurus a system of logic, physics and ethics that seemed compatible with early seventeenth century empirical observations. From Epicurus, Aristotle’s near contemporary, Gassendi constructed a framework which he thought could support both the new experiments and Christian teaching. Demonstrating the consistency of Epicureanism with seventeenth-century Catholic Christianity was quite a challenge for two reasons. First was the basic atheistic premise of Epicureanism, and the associated beliefs in ethics based on pleasure and the mortality of the human soul. In antiquity, Epicureanism had been considered the worst of all philosophical systems by nearly every other ancient philosophy, both pagan and Christian, because of these tenets. Second, Epicurean physics advocated physical concepts such as the eternity of the cosmos, the existence of other worlds in space and time, the existence of a void, and the atomic structure of all substances which were sharply opposed to the prevailing Christianized Aristotelian physics. Little previous research has examined in detail Gassendi’s efforts to reconcile Epicureanism and Christianity. Analyzing how Gassendi tried to use the Christian classics in support of his natural philosophy reveals some of the early signs of the fissures that were developing between science and religion. For instance, Gassendi supported the Copernican cosmology until the Church’s 1633 condemnation of Galileo. At that point 7 he moved to the Tychonian system as an alternative because it was consistent with both Church teaching and empirical data. My research interest focuses on how Gassendi tried to create a philosophical synthesis which combined seemingly irreconcilable methods (empiricism and humanism) and philosophies (Epicureanism and Christianity). 8 Slide 5 Epicureanism and Modifications To justify his use of Epicureanism, Gassendi first had to refute the damaging ad hominem attacks against Epicurus himself that dated to antiquity. Gassendi claims that the Church Fathers misunderstood and misinterpreted Epicurus, especially his ethics. He argues that Epicurus’s personal ethics had more in common with Christian ethics than many other ancient pagan philosophers. Gassendi calls upon Origen in Contra Celsum and Augustine in the City of God to bear witness that Epicurus was no worse, and perhaps better, than other pagan philosophers.9 Gassendi sets about “Baptizing Epicurus” (Margret Osler’s phrase)10 by making God the author of the most objectionable Epicurean tenets. For instance, he asserted that God created the atoms and gave them their motion and proclivity to combine in order to form other substances. Similarly, Gassendi argues that God created man to seek pleasure. Therefore pleasure could be an appropriate basis for Christian ethics. 9 Ibid., 5:200-202. Margaret Osler, Divine Will and the Mechanical Philosophy, Gassendi and Descartes on Contingency and Necessity in the Created World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) 22. 10 9 Slide 6 Gassendi and the Christian Classics Gassendi looks to the Bible and the Church Fathers to validate his systematic philosophy. Although the Church Fathers were typically not interested in physics per se, they were deeply concerned about the reconciliation of Scripture with observed natural phenomena. It was typically in this context that the Fathers wrote about physics, astronomy and cosmology, often as a commentary on Genesis. Gassendi analyzes patristic arguments throughout his own development of physics. As Harry Brundell has observed, one of the key reasons for Gassendi’s use of the early Church Fathers is their opposition to Aristotle. At the very beginning of Gassendi’s massive Syntagma Philosophicum, he writes: The early Church Fathers were particularly opposed to Aristotle and his philosophy, and they displayed extreme animosity against the followers of Aristotle. But when some philosophers were converted to the faith, they began to set aside the more serious errors of Aristotle. What remained of Aristotelian philosophy was then accommodated to religion so successfully that it was no longer suspect and finally became the handmaid ministering to religion. Therefore I say, just as it was possible in the case of Aristotelian philosophy, which is now taught publicly, so it is possible with other philosophies such as the Stoic and Epicurean. All of them have much that is of value and worthy of being learned once the errors are eliminated and refuted in the same way as the very grave errors of Aristotle were refuted.11 This passage encapsulates Gassendi’s approach to Christianizing Epicureanism. The way to justify Epicureanism is first to reject Aristotle, as the Church Fathers had done, and then to recognize that later theologians were able to use Aristotle in theology after correcting his “grave errors.” Just so, Gassendi argues he should be allowed to do the same for Epicurus’s philosophy. 11 Harry Brundell, Pierre Gassendi, From Aristotelianism to a New Philosophy (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1987), 52. (Gassendi, I:5) 10 As an example of his approach, lets consider the way in which Gassendi appealed to both experimental and humanists ‘data’ to support his arguments for the existence of a void against the prevailing theory. 11 Slide 7 The Problem with a Void Epicurus had suggested that atoms move in a void with a random swerve that accounts for the variation and uncertainty observed in nature and men. But the standard description of nature as taught in the schools of the Middle Ages was based on Ptolemy's magnum opus, the Alamgest, together with Aristotle's On The Heavens and On Physics. These were the authoritative cosmological and physical treatises. The fundamental reasons for the rejection of a void are found in Aristotle’s On the Heavens (I.9.279a.1017) in which he states that there is only one world; that voids do not exist; and time is the number of motion of natural bodies.12 One further point of Aristotelian understanding needs to be explained as it relates to the void, and that is Aristotle’s definition of velocity found in the Physics.13 Aristotle argued that speed was inversely proportional to the density of the medium through which the object moves. Therefore a rock thrown in water will move slower than one thrown in the air. By this reasoning, a rock thrown in a vacuum would move with infinite velocity, which is not possible. Two conclusions result: first, a vacuum cannot exist; and second, natural motion is circular. The reconciliation of Aristotle's physics and the descriptions found in the Bible dominated the university discussions from the thirteenth through the seventeenth centuries. As Edward Grant described in detail, official ecclesial opposition to a void was codified in 1277 when the bishop of Paris, Etienne Tempier, issued a series of 219 12 Aristotle, On the Heavens, trans. Guthrie in Grant, Planets, Stars and Orbs, The Medieval Cosmos, 12001687 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 169. 13 Aristotle, Physics, trans. Philip Wicksteed, Loeb Classics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952), 417-425. 12 condemnations of heretical views. These condemnations were very influential, especially after they received support from Pope John XXI. Two condemnations in particular denounced the idea of a void: Condemnation 66 argued that God could not move the heavens in a straight line otherwise there would be a vacuum; and Condemnation 190 argued that empty space did not exist before God created the world.14 14 Edward Grant, Much Ado About Nothing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 108-110. See also Lolordo, Pierre Gassendi and the Birth of Early Modern Philosophy, 109-110. 13 Slide 8 Gassendi’s Empirical and Historical Evidence for a Void To refute this standard position, Gassendi invoked both experimental data and the Christain classics. For experimental support he points to three classes of experiments to demonstrate the existence of void: chemical, barometric and dynamic. The chemical experiments suggested by Gassendi were based on dissolving compounds in water. He reasoned that since salts and other compounds dissolved in water can be reconstituted from evaporated water that the dissolved particles must reside in void spaces mixed in with the water.15 Saul Fisher has described the impact of the barometric experiments by Torricelli and Pascal on Gassendi’s thought.16 In these experiments, a U-shaped tube, sealed at one end, was filled with mercury. Then the apparatus was carried to a higher altitude, causing the mercury to partially empty from the tube. The question becomes what, if anything, fills the gap between the new, lower mercury level and the sealed end of the tube. Gassendi (and Pascal) argued that only a void could remain in the gap.17 Thus having established that a void could be artificially created, Gassendi suggested that voids or vacuums could also appear in nature.18 15 Ibid., 1:195-196. Saul Fisher, Pierre Gassendi, 128-132. 17 Being the expert empiricist that he was, Gassendi recognized as a valid argument against a void that light could pass through the gap. Relying on his atomism for an explanation, Gassendi allowed that the gap was not completely void, but there still remained some atoms mixed with a void in the gap through which light could ‘flow’. Note that the discounting of an aether or other material required for light to travel through did not occur until the Michelson-Morely Experiment of 1887. 18 This description is found in both the Appendix to his Animadversiones (3:iij-xxiij) and the Syntagma (I:203-216). 16 14 Perhaps his most important empirical arguments were those based on motion. Commenting on Galileo’s Diologo, Gassendi described19 his key experiment that confirmed Galileo’s theory of dynamics: the famous ship experiment. In this experiment, he demonstrated that balls dropped from the mast of a moving ship fall at the foot of the mast, regardless of how fast the ship is moving.20 Paolo Galluzzi describes how this experiment led Gassendi to develop several important insights into the laws of dynamics. First, that all motion was relative. The motion of the balls when they are released from the mast ‘includes’ the horizontal motion of the ship. Another insight that Gassendi formulated was the law of inertia. He believed that his experiment demonstrated that only an external force acts on the balls, and further that unless an external force acts in some way, a body will continue in motion indefinitely. This led to Gassendi’s succinct statement that a body moving in a vacuum will perpetually continue in a straight line at a constant speed.21 This was the first written statement of the law of inertia. Gassendi also found empirical evidence for empty space in the observed motion of celestial bodies and the barometric experiments.22 He argued that the motion of celestial bodies was such that most of the space between them was empty or an extramundane void, since celestial bodies were not observed to ‘hit’ or encounter any 19 The De Motu Impresso is a collection of three letters written by Gassendi to Pierre Du Puy. These letters were circulated among the Mersenne network as a unit, and Gassendi intended that they be considered as a unit. The De Motu is found in 3: 478-563. 20 Paolo Galluzzi, “Gassendi and L’Affaire Galilee of the Laws of Motion,” in Galileo in Context. ed. Jurgen Renn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 239-276. 21 Ibid., 1: 343; trans. Brush, 385. 22 Ibid., I:195-196. 15 other bodies. Even more controversially, Gassendi suggested that there existed a void in the sub-lunar region between the moon and the earth.23 His reasoning for a sub-lunar void was based on the barometric experiments. Gassendi repeated those experiments at different altitudes. As the altitudes increased, the gap in the sealed mercury column increased. Gassendi reasoned that this indicated as one moved toward the moon, air was becoming thinner and thinner, and that eventually there would be no air or anything else, only a void. Gassendi juxtaposes this type of experimental evidence next to evidence from the history of philosophy and theology. For historical Christian evidence of a void, Gassendi notes that angels are said to be in space without being corporeal. Further angels can penetrate corporeal things such as stone and walls, and yet angels have no corporeal dimension. Edward Grant notes that Gassendi extends the analogy between angels and a void by turning to Nemesius who suggested that grace and space were made incorporeal per se.24 Nemesius, fourth century bishop of Emesa, was best known for his On Human Nature which was well received in antiquity and used in the Middle Ages as an authoritative Christian source. However, it must be allowed that Nemesius is at best a secondary figure; it is telling that Gassendi must appeal to him as patristic support for this important concept. Gassendi looked for additional theological support for an extramundane void from Irenaeus. He notes that the second century bishop of Lyons equated the Greek kenoma with the Latin inane. In a reference to Irenaeus, Gassendi points out that “certain of the 23 24 Ibid., I:182; trans. Brush, 386. Ibid., 1:219. See also Grant, Much Ado About Nothing, 21-22. 16 Fathers in order to argue against the Valentinians call it kenoma.”25 He observes that Irenaeus had separated the notion of void from God in his arguments, implying (in Gassendi’s view) than an infinite void could exist.26 Ibid., 1: 185. “specialeque est aliquorum Patrum, ut dum adversus Valentinios disputant, ‘to kenoma’ vocent.” 26 Irenaeus, Against the Heresies II.4, ANF Vol. 1, trans. Coxe (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1995), 362-363. 25 17 Slide 9 Implications of a Void: Nature of Space and Time This discussion highlights how several basic concepts in medieval and early modern physics were inter-related. What one thought about the void effected how one thought about the nature of space and time, and motion. Because Gassendi believed in the reality of a void, he also asserted that dimensionality is not the same thing as a body, which is defined by substance and accidents. “We conclude that space and time must be considered real things, or actual entities, for although they are not the same sort of things as substance and accident are commonly considered, they still actually exist.”27 Among the properties of both space and time are their infinitude and Gassendi comes very close to asserting that they are eternal. Antonia Lolordo has stressed this line of reasoning in Gassendi.28 Empty space and time exist independently of God; God creates corporeal entities in space and time. Gassendi asserts, without giving any references, that the majority of the Sacred Doctors agree with this.29 Just as space can be measured by extended bodies, but is not the same thing as an extended body, so time can be measured by the motions of celestial bodies, but time itself is not the motion of celestial bodies. “Whatever it (time) is, it would appear to be something incorporeal, like the void.” 30 27 Gassendi, 1:182; trans. Brush 384. Antonia Lolordo, Pierre Gassendi and the Birth of Early Modern Philosophy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 110-127. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid., I:, 223; trans. Brush, 393. 28 18 Gassendi directly challenged the scholastic view through a discussion on the eternity of essences. He argues that it is easier to accept the notion that space is uncreated and independent of God which is “a concept that appears to be far more acceptable than another that the doctors commonly admit, namely that the essences of things are eternal, uncreated and independent of God.”31 Although no specific reference is given, he seems to be referring to Aquinas, especially his On Being and Essence. If so, he is overstating Aquinas’s position. It is true that Aquinas believed in the eternity of essences, but certainly not that they were independent of God. 31 Ibid., I:184; trans. Brush, 389-390. 19 Slide 10 Evidence of Space and Time For patristic support of the distinction of space ant time from corporeal bodies, Gassendi again turned to Nemesius: “Let what Nemesius has to say stand for them all, ‘Indeed every body is endowed with three dimensions, but not everything endowed with three dimensions is a body. Of this sort are place and quantity which are incorporeal entities (entia).” 32 Gassendi begins his discussion of time with Augustine and the Confessions Book 11: “Everybody quite rightly remembers what Saint Augustine said: ‘If no one asks me what time is, I know the answer; if I wish to explain it to an inquirer, I do not know it.’ ”33 Gassendi expands on Augustine: …whatever it is it would appear to be something incorporeal, like the void… Then in the same way that space was described earlier as an incorporeal and immobile extension in which it is possible to designate length, width and depth so that every object might have its place, so time may be described as an incorporeal fluid extension in which it is possible to designate past, present and future so that every object may have its time.34 The concept of time as distinct from motion allows Gassendi to interpret Joshua’s battle at which the sun stood still and the day lasted longer than any day before or since (Josh. 10).35 In this interpretation, Josh. 10 does not imply that time stood still, only that time could no longer be measured by the revolution of the sun. 32 Ibid; 1:182; trans. Brush, 385. Here and elsewhere Brush translates entia as beings; this I think gives a poor connotation of what Gassendi is saying. I have translated it as entities. Gassendi does not in any way mean to imply that empty space is a tangible thing which ‘being’ might connote. 33 Gassendi, 1:220; trans. Brush, 390. 34 Ibid. 35 Gassendi, 1:225, gives Joshua 10:14 as “non fuisse ullum neque antea neque postea tam longum diem” whereas the Vulgate has “non fuit ante et postea tam longa dies.” 20 Gassendi asserted that time, like his concept of space, exists outside of creation. “Before the creation of the universe a certain time flowed by…a time which flows during the existence of the universe and will continue to flow when the universe ceases to be.”36 To argue for the eternal existence of time, or at least time independent of creation, Gassendi turned to Scripture and Pope Gelasius. He finds biblical support of infinite expanse of time in: Psalm 101:27-28, They shall be changed. But thou art always the selfsame, and thy years shall not fail. They shall be changed. Exodus 3:14, I am who am, Who Is sent me to you. Revelation 1:8, Who is and who was and who is to come Gassendi observed that many of the Church Fathers, including Augustine, Gregory Nazianzus, and John Damascene did oppose the notion of infinite duration of time. Gassendi claimed this puts Augustine (and others) at odds with Gelasius’s account of the Council of Nicea. According to Gassendi, Gelasius defined eternity as infinite time, as represented by “In the beginning was the Word.” The ‘was’ refers to time before creation.37 What Gassendi fails to note is that Nicea and Gelasius are arguing against the Arians, and their notion that the Son was not coeternal with the Father; Gelasius was not discussing the nature of time. 36 37 Ibid., 1: 224; trans. Brush, 394. Ibid., 1: 228. 21 Slide 11 Impact of Gassendi’s Understanding of Space and Time Gassendi was perceptive and even revolutionary in his understanding of void, space and time. His arguments on these concepts form a bridge to his understanding of incorporeal substances (God, angels, human intellect) and corporeal substances (composed of atoms). God creates incorporeal and corporeal entities in space and time. Thus in Gassendi there are three classes of entities (space and time, incorporeal substances, and corporeal substances) each with its own ‘physics’ that can be investigated both empirically and historically. The similarity between space and time, and their independence from corporeal bodies, is quite modern and informed Newton’s understanding of space. Of particular importance was Gassendi’s separation of measurement from the thing measured. Thus space and time could be measured by extended corporeal bodies, without implying that space and time themselves must be corporeal bodies or the motion of corporeal bodies. 22 Slide 12 Conclusions The vacuum pump was invented shortly before Gassendi’s death, but there is no indication that he had an opportunity to experiment with one. However, the next generation of physicists, especially Boyle and Newton, were able to use the vacuum pump to develop a physical understanding of the properties of a vacuum, much as Galileo used the telescope to observe the planets. The scholastic objections to a void, like the objections to a heliocentric solar system, passed into oblivion by the end of the seventeenth century. Many of the most prominent philosophers and scientists of the next generation were deeply influenced by Gassendi. But his influence outstripped his fame and his works. His intellectual model that embraced both empiricism and Christian humanism was quickly eclipsed. Although used as a source for Epicureanism, for instance by Thomas Jefferson, his method of painstaking analysis of ancient authors was quickly left behind. The style of the Christian humanist was not suitable to the new style of the scientist as it developed in the eighteenth century. Gassendi’s emphasis on the nuance of words was replaced by an emphasis on the apparent certainty of mathematics as the best way to describe nature. Thank you for your time and attention this morning. Are there any questions or comments? 23 Bibliography Pierre Gasendi Primary Sources and Translations Gassendi, Pierre. Opera Omnia in sex tomos divisa. Vol. 1-6. Lyons: 1658. Reprinted in facsimile. Stuttgart-Bad Canstatt: Friedrich Frohmann, 1964. ______ Pierre Gassendi’s Institutio Logica 1658. Edited and translated by Howard Jones. Assen:Van Gorcum, 1981. ______ Collected works available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ ______ Selected Works of Pierre Gassendi. Translated by Craig Brush. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1972. ______ Vie et Moeurs d’Epicure. Traduction, introduction, annotations. Translated (French) by Sylvie Taussig. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2006. ______ Three Discourses of Happiness, Virtue and Liberty. Translated by Monsieur Bernier. London, 1699. ______ On Happiness. Translated by Erik Anderson, available at http://www.epicurus.info/etexts/gassendi_concerninghappiness.html. ______ Life of Copernicus. Translated by Olivier Thill. Fairfax: Xulon Press, 2002. Ancient Sources Aristotle. Physics. Translated by Philip Wicksteed. Loeb Classical Library 2 Vol. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952. ______ On the Heavens. Translated by W.C. Guthrie. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960. Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. 2 Vols. Translated by R.D. Hicks. Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1972. Lucretius. De Rerum Natura. Edited by Leonard and Smith. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1942. Usener, Hermann. Epicurea. Edited and translated [Italian] by Giovanni Reale. Milan: Bompiani, 2002. 24 Other Sources Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of English Dominican Province, http://www.newadvent.org/summa/100101.htm, accessed 31 May 2006. Augustine. City of God. Translated by Henry Bettenson. London: Penguin, 1984. ______ Confessions. Translated by Henry Chadwick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. ______ Tractates on John. Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers Series 1 Vol 7. Translated by Browne. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1994. ______ On Free Choice of the Will. Translated by Thomas Williams. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993. Boethius. Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by Richard Green. New York, Macmillan, 1962. Epicurus. The essential Epicurus: letters, principal doctrines, Vatican sayings, and fragments. Translated by Eugene O'Connor. Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1993. Galileo Galilei. Letter to Grand Duchess Christina of Tuscany, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/galileo-tuscany.html, accessed 31 May 2006. Irenaeus. Against the Heresies. Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 1. Translated by Coxe. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1995. Newton, Isaac. Opticks. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952. First published 1704. ______ “Letter to Robert Hooke,” 5 Feb. 1676. ______ Observations on the Prophecies of Daniel and St. John. Edited by S. J. Barnett. Wales: Edwin Mellen, 1999. Copernicus, Nicholas. On the Revolutions. Translated by Edward Rosen. http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~matc/Readers/renaissance.astro/1.1.Revol.html accessed 31 May 2006. Pascal, Blaise. The Treatise on the Equilibrium of Liquids and on the Weight of the Mass of the Air. Translated by W. F. Trotter in Pascal Great Books of the Western World Vol 33. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952. 390-429. 25 Secondary Sources Secondary Sources on Pierre Gassendi Bloch, Olivier. La philosophie de Pierre Gassendi. Nominalisme, materialisme et metaphysique. La Haye: Martinus Niejhoff, 1971. ______ “Gassendi and the Transition from the Middle Ages to the Classical Era.” Yale French Studies 49. Science, Language and the Perspective of the Mind: Studies in Literature and Thought from Campanella to Bayle (1973) 43-55. Brundell, Barry. Pierre Gassendi, From Aristotelianism to a New Philosophy. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1987. Fisher, Saul. Pierre Gassendi’s Philosophy and Science, Atomism for Empiricists. Boston: Brill, 2005. ______“Pierre Gassendi” Stanford University On-Line Dictionary of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/gassendi/. Accessed 28 July, 2006. ______ “Gassendi’s Atomist Account of Generation and Heredity in Plants and Animals.” Perspectives on Science 11, no. 4. (2003): 484-508. Galluzzi, Paolo. “Gassendi and L’Affaire Galilee of the Laws of Motion.” In Galileo in Context, ed. Jurgen Renn, 239- 276. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Garber, Daniel. “Soul and Mind: Life and Thought in the Seventeenth Century.” In The Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Garber, 759-795. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ______ “New Doctrines of Body and Its Powers, Place and Space.” Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, 553-623. Gorman, Mel. “Gassendi in America.” Isis 55, no.4 (1964): 409-417. Grant, Edward. Much Ado About Nothing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. Gventsadze, Veronica. “Human Freedom in the Philosophy of Pierre Gassendi.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, 2001. Jolley, Nicholas. “The relation between philosophy and theology.” In The Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Garber, 363-392. Cambridge: 26 Cambridge University Press, 1998. Jones, Howard. Pierre Gassendi 1592-1655 An Intellectual Autobiography. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graff, 1981. Joy, Lynn. Gassendi the Atomist. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. _____ “Epicureanism in Renaissance Moral and Natural Philosophy.” Journal of the History of Ideas 53, no. 4 (Oct. – Dec. 1992): 572-583. Kraye, Jill. “Conceptions of Moral Philosophy.” In The Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Daniel Garber, 1279-1316. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Larmore, Charles. “Scepticism.” In Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Garber, 1145-1192.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Lennon, Thomas. The Battle of the Gods and Giants, the Legacies of Descartes and Gassendi. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993, 5. Lolordo, Antonia. “The Activity of Matter in Gassendi’s Physics.” In Early Modern Philosophy, ed. Daniel Garber, 75-103. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ______ Pierre Gassendi and the Birth of Early Modern Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Mazauric, Simone. Gassendi, Pascal, et la Querelle Du Vide. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1998. McCracken, Charles. “Knowledge of the Soul.” In Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. by Daniel Garber, 796 - 832. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Michael, Fred and Emily Michael, “The Theory of Ideas in Gassendi and Locke.” Journal of the History of Ideas 51, no. 3 (Jul – Sep 1990): 379-399. Miller, Peter. Peirsec’s Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. Murr, Sylvia. “Foi religieuse et libertas philosophandi chez Gassendi.” Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques 76 (Jan. 1992): 85-100. ______ “Pierre Gassendi – Preliminaires a la Physique Syntagma Philosophicum.” XVIIe Siecle 45 (1993): 353-485. ______Gassendi et l’Europe. Librairie Philosophique. Paris: J. Vrin, 1997. 27 O’Conner, J. J. and E.F. Roberston, Marin Mersenne, http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Mersenne.html School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St. Andrews, Scotland, accessed 24 November 2006. Osler, Margaret. “The History of Philosophy and the History of Philosophy: A Plea for Textual History in Context.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 40 no. 4 (2002): 529-533. ______ “Early Modern Uses of Hellenistic Philosophy, Gassendi’s Epicurean Project.” In Hellenistic and Early Modern Philosophy, ed. Jon Miller and Brian Inwood, 30-44. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ______ “When Did Pierre Gassendi Become a Libertine?” In Heterodoxy in Early Modern Science and Religion, ed. Brooke and MacLean, 169-192. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ______ “New Wine in Old Bottles: Gassendi and the Aristotelian Origin of Physics.” In Midwest Studies in Philosophy, ed. French and Wettstein, 167-184. Boston: Blackwell, 2002. ______ Divine Will and the Mechanical Philosophy, Gassendi and Descartes on Contingency and Necessity in the Created World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ______ Rethinking the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Palmerino, Carla. “Gassendi’s Reinterpretation of the Galilean Theory of Tides.” Perspectives on Science 12, no. 2 (2004): 212-237. Pancheri, Lillian. “Pierre Gassendi, a forgotten but important man in the history of Physics.” American Journal of Physics 46, no.5 (May 1978): 455-463. Pintard. René Le libertinage érudit dans la première moitié du XVIIe siècle. Genève: Slatkine, 1983. Reprint Paris: Boivon, 1943. Popkin, Richard. The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. ______ “Pierre Gassendi.” In Great Thinkers of the Western World, ed. Richard Popkin, 191-195. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ______ Philosophy of the 16th and 17th Century. New York: Free Press, 1966. Rochot, Bernard Les Travaux de Gassendi. Paris: J. Vrin, 1944. 28 Sarasohn, Lisa. Gassendi’s Ethics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996. ______“Epicureanism and the creation of a privatist ethic in early seventeenth century France.” In Atoms, Pneuma and Tranquility, ed. Margaret Osler, 175-195. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Sepkoski, David. “Nominalism and constructivism in seventeenth-century mathematical Philosophy.” Historia Mathematica 32 (2005): 33-59. Sleigh, Robert. et al. “Determinism and Human Freedom.” In Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Daniel Garber, 1195-1278. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Spink, J. French Free thought from Gassendi to Voltaire. London: University of London, Press, 1960. Wallace, Wes. “The vibrating nerve impulse in Newton, Willis and Gassendi: First steps in a mechanical theory of communication.” Brain and Cognition. 51 (Feb. 2003): 66-94. Secondary Sources on Ancient Philosophy and Church Fathers Amis, Elizabeth. “Epicurean Epistemology.” In Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy, ed. Algra et. al. 260-294. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Cohen, S. Marc. “Aristotle’s Metaphysics.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-metaphysics/. Accessed 1 March 2007. Copleston, Frederick. A History of Philosophy, Vol. I. New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1946. ______ A History of Philosophy, Vol II, Augustine to Scotus. New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1950. DeWitt, Norman. Epicurus and his philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1954. Harry, Brigid. “Epicurus: Some Problems in Physics and Perception.” Greece and Rome, 2nd Ser. 17, no. 1 (Apr. 1970): 58-63. Johnson, Monte and Catherine Wilson. “Lucretius and the History of Science.” forthcoming in Cambridge Companion to Lucretius. Available at http://philsciarchive.pitt.edu/archive/00002705/01/Lucretius_and_the_History_of_Science_co 29 mplete.pdf#search=%22aneponymus%22. Accessed 29 August 2006. Jungkuntz, Richard. “Christian Approval of Epicureanism.” Church History 31, no. 3 (Sept 1962): 279-293. O’Daly, Gerard. Augustine’s City of God. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Sedley, D. Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Simpson, Adelaide. “Epicureans, Christians, Atheists in the Second Century.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 72 (1941): 372-381. Other Secondary Sources Armogathe, Jean-Robert. “Proofs of the Existence of God.” In Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Garber, 305-330. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Ashworth, William. “Christianity and the Mechanical Universe.” In When Science and Christianity Meet, ed. Lindberg and Numbers, 61-84. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ______ ”Catholicism and Early Modern Science.” In God and Nature, ed. Lindberg and Numbers, 136-166. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986. Biagioli, Mario. Galileo, Courtier. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. Blackwell, Richard. Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991. Burrell, D. Aquinas: God and Action. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979. Christianson, Eric and Terry McWillimas. “Voltaire’s Precis of Ecclesiastes, A Case Study in the Bible’s After Life.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 29, no. 4 (2005): 455-484. Cohen, J. Bernard. Revolution in Science. Cambridge: Belknap, 1985. Cohen, Eric. “The Ends of Science.” First Things 167 (Nov. 2006): 27-33. Dahm, John. “Science and Apologetics in the Early Boyle Lectures.” Church History 39, no. 2 (Jun 1970): 172-186. 30 Deigh, John. “Reason and Ethics in Hobbes’s Leviathan.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 34, no.1 (Jan 1996): 33-60. De Grazia, Margreta. “The Secularization of Language in the Seventeenth Century.” Journal of the History of Ideas 41, no.2 (Apr – Jun 1980): 319-329. Dobbs, B. J. T. “Stoic and Epicurean doctrines in Newton.” In Atoms, Pneuma and Tranquility, ed. Osler, 197-219. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Garber, Daniel. “Descartes, Mechanics, and the Mechanical Philosophy.” In Midwest Studies in Philosophy, ed. Peter French, et al., 185- 204. Malden: Blackwell, 2002. Garfinkel, Alan. “Reductionism.” In The Philosophy of Science, ed. Boyd, Gasper, Trout, 443-459. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991. Ginzburg, Carlo. “High and Low: The Theme of Forbidden Knowledge in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.” Past and Present 73 (Nov. 1976): 28-41. Griffin, David. Two Great Truths: A New Synthesis of Scientific Naturalism and Christian Faith. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2004. Halabi, Selman. “A Useful Anachronism: John Locke, the Corpuscular Philosophy, and Inference to the Best Estimate.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. 36 (2005): 241-259. Jesseph, Douglas. “Hobbes’ Atheism.” Midwest Studies in Philosophy, XXVI (2002): 140-166. Johns, Adrian. “The birth of scientific reading.” Nature 409 (18 Jan 2001): 287. Kroll, Richard. The Material Word: Literate Culture in the Restoration and Early Eighteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. ______ “The Question of Locke’s Relationship to Gassendi.” Journal of the History of Ideas 45, no.3 (Jul – Sep 1984): 339-359. MacIntosh, J. J. “Boyle on Epicurean atheism and atomism in Atoms.” In Atoms, Pneuma and Tranquility, ed. Margaret Osler, 197-219. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Murphy, Mark. “Desire and Ethics in Hobbes’s Leviathan.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 38, no.2 (2000): 259-268. Neto, Jose. “Academic Skepticism in Early Modern Philosophy.” Journal of the History 31 of Ideas. 58, no.2 (1997): 199-220. Newman, Lex. “Descartes’ Epistemology.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/descartes-epistemology/ accessed 1 December 2006. Norton, David Fate. “The Myth of British Empiricism.” History of European Ideas, 1 (1981): 331-342. Rist, John. Epicurus: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972. ______ Real Ethics: Rethinking the Foundations of Morality. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2001. Sanford, Charles. The Religious Life of Thomas Jefferson. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1984. Schmaltz, Tad. “What has Cartesianism to do with Jansenism?” Journal of the History of Ideas 60, no.1 (1999): 37-56. Thiel, Udo. “Personal Identity.” In Cambridge History of Seventeenth Century Philosophy, ed. Daniel Garber, 868-912. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Trinkaus, Charles. In Our Image and Likeness. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. 1995; First Published University of Chicago Press, 1970. Westfall, Richard. “The Rise of Science and the Decline of Orthodox Christianity: A Study of Kepler, Descartes, and Newton.” In God and Nature, Ed. Lindberg and Numbers, 218-237. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986 ______ Never at Rest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980. Williams, Garrath, “Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Feb. 2002. Available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hobbesmoral/ Accessed 7 October 2006.