Colonial customs such as requiring the family of the deceased to

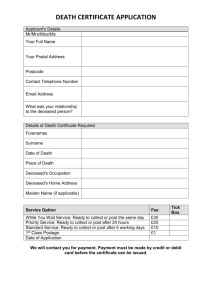

advertisement

Colonial customs such as requiring the family of the deceased to give gifts of mourning rings or gloves to mourners were losing popularity. This practice is documented as far back as the Middle Ages, when money was set aside in wills to purchase mourning rings for certain family members and friends.5 The mourning rings would often have a small receptacle in the center for a locket of hair from the deceased. But in the last half of the nineteenth century, mourning began to take on a different character, influenced primarily by Queen Victoria of England. Her husband of twentyone years, the former Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg Gotha (a German State), died on 14 December 1861. Victoria had been completely devoted to and dependent upon Albert, and his loss affected her deeply. She began to wear a widow’s cap and gave instructions for mourning decorations to be hung liberally throughout the kingdom. In the 1860s, flowers were not yet part of mourning customs; instead, black drapes were hung at the house of mourning. The wife of the deceased was expected to wear black for a minimum of a year. Other family members’ mourning periods varied according to their relationship to the deceased.6 One of Victoria’s biographers, Stanley Weintraub, noted: Mirroring her mourning, the Household, at the Queen’s instruction, went about in black crêpe, broadcloth, and bombazine, underscoring the gloom. For a year after Albert’s death, no member of her Household could appear in public except in mourning garb, a practice that might have continued indefinitely had her ladies not sunk so much in morale that Victoria relented sufficiently to permit "semimourning" colors of white, mauve, and grey. Even royal servants were obliged to wear a black crêpe band on the left arm until 1869.7 Although the monarch of one of the most powerful countries in the world, Victoria was in seclusion for about five years after Albert’s death–too long for her subjects and the British press. One person went so far as to post a handbill on the wall of Buckingham Palace that read, "These extensive premises to be let or sold, the late occupant having retired from business."8 The American public–as fascinated with the English monarchy then as it is today–was sympathetic to the Queen’s grief even though it was preoccupied with the Civil War. With the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, public mourning in the United States paralleled the experiences of the British public following the death of their "uncrowned king." Embalming had grown in acceptance during the war, being used to slow a body’s decomposition until transportation and burial. Because Lincoln was embalmed, his body was able to be viewed by mourners in Washington, D.C., New York, and Chicago before he was buried in Springfield, Illinois.9 Gloom and darkness were the hallmarks of mourning in late nineteenth-century Victorian America and many mourning symbols appeared during this period. Mourning symbols included jewelry made of hair and jet (a lightweight material from the coal family),10 coffin photographs of the deceased, memorial cards with and without photos of the deceased, mausoleums, and, in smaller towns, lengthy obituaries. Hairwork jewelry grew out of the desire to keep a part of a loved one close to the wearer. Godey’s Lady’s Book of December 1850 introduced the craft to American women, which soon became a popular pastime. While not used exclusively for mourning, hairwork jewelry was a natural way to remember a deceased loved one. The Godey’s Lady’s Book of May 1855 contained the following summary: Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials, and survives us, like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look up to heaven and compare notes with the angelic nature–may almost say, "I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now."11 Hairwork jewelry took various forms including brooches, bracelets, watch chains, and earrings. A jeweler would put the finishing touches on the piece to make it wearable. The Knightsbridge Antique Mall in Northville, Michigan, displays a beautiful example of a hairwork brooch made circa 1850—60, which they courteously allowed to be photographed. The brooch has loops of intricately woven hair, cinched in the middle by a gold clasp engraved with the word "Mother," with three hairwork tassels dangling from the center. Hairwork took on larger dimensions in artistic ensembles preserved in shadow boxes. The Plymouth, Michigan, Historical Museum has two hairwork shadow boxes on display that can be dated to the latter half of the nineteenth century. Jet was popularized as a material for mourning jewelry by Queen Victoria, who wore the stone both in mourning for King William IV, her predecessor, and for her husband Albert. Jet was lightweight and easy to carve so it became a useful material for making the large brooches and necklace designs that were popular during the period. Funeral cards have been around for centuries, but their use has changed over time. Originally created to invite mourners to a funeral, today they frequently appear in funeral homes during wakes as a memento of the deceased. (See p. 21 for more information on memorial cards.) Another visual symbol of the mourning style of the Victorian era is the large mausoleums built in the new, beautifully landscaped, park-style cemeteries that began appearing. In earlier days, people were more frequently buried in churchyards or family plots than in community cemeteries. The fear of the spread of infectious diseases was one of the motivations for the creation of large cemetery tracts on the outskirts of towns. Some of these cemeteries tried hard to emulate a park-like environment, making a visit to the cemetery a more pleasant experience. Some people spent extravagant sums of money to memorialize their loved ones in mausoleums or with artistic headstones in the form of a tree stump, a cherub, or other classic designs. The Hein mausoleum in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Detroit was built to commemorate Otto Hein, a proprietor of Ziervogel and Hein Funeral Home. Photography was a very popular pastime in Victorian America and, according to author Maureen Delorme, "postmortem photography of the deceased, especially of children, was a virtual obsession to nineteenth century Americans."12 Bereaved families wanting to keep a memory of a lost child would have a photo made of the child lying in its coffin. Some of these photos were given to family members and friends or appeared on memorial cards announcing the child’s death. The Plymouth Historical Museum’s collection contains both a photo of Elnora Horn, a pretty young girl, and one of Elnora taken perhaps a year later, laid out in her coffin. The photos were donated by Lillian Hartmann, a childhood friend.