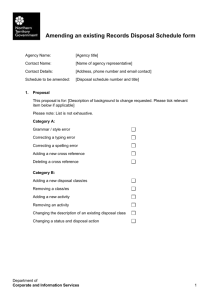

Ian Sampson, Partner:Environmental

advertisement

THE LEGAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE TREATMENT AND DISPOSAL OF MEDICAL WASTE IN SOUTH AFRICA Ian Sampson Partner, Environmental & Sustainability Law, Shepstone & Wylie Attorneys Tel: (031) 566-8260 ; Fax: (031) 566-2097 ; Cell: 082 775 3720 ABOUT THE SPEAKER Ian is an environmental lawyer. He is a member of the environmental committee of the Institute of Directors of Southern Africa, the chairman of the environmental committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in South Africa and the co-chairman of the environmental committee of the Durban Chamber of Commerce. He has written or edited several books, including the Guide to Environmental Auditing in South Africa (Butterworths, December 2000) and a Legal Framework to Pollution Management in South Africa (Water Search Commission, 2001). He acts for both private and public sector clients on a range of environmental regulatory issues. ABSTRACT From no regulation to over regulation? From fragmented regulation to a co-ordinated, holistic approach? From confusion to clarity? Until the recent waste management developments at a national and regional level, an apparent vacuum in appropriate healthcare waste management laws existed in South Africa. Based on an erroneous interpretation of the Human Tissues Act, the Department of Water Affairs & Forestry has required, until recently that all-healthcare waste be incinerated. This resulted in certain instances of efficient healthcare waste incineration by certain operators, but largely inefficient incineration by the vast majority of healthcare waste generators often through poorly maintained and inappropriate burners at healthcare facilities. However with the development of the National Waste Management Strategy, the National Waste Management Bill (still to be officially published for comment) and regional initiatives such as the Gauteng Healthcare Waste Strategy and the Draft to KwaZulu-Natal Waste Policy, an improved, more effective regulatory framework is emerging. The paper will look at the historical healthcare waste management laws, and discuss the environmental and liability implications they create and the liability legacy they will leave. It will then consider the emerging regulatory framework and describe the new or emerging standards healthcare waste generators, handlers, transporters and disposes need to comply with. It will discuss the fact that although a single national waste management law is being developed, there are a range of other laws at a national, provincial and local level which those involved with healthcare waste need to consider. THE LEGAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE TREATMENT AND DISPOSAL OF MEDICAL WASTE IN SOUTH AFRICA 1 INTRODUCTION There is currently no clear legal directive on how medical waste must be treated and disposed of. Pending or proposed laws and standards do not, at this stage, appear to be going to satisfactorily address this lack of clarity. 2 CURRENT LAW 2.1 An apparent misunderstanding There appears to have been a consistent, and thus far inexplicable, misinterpretation of the Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983. This error appears to have been consistently applied over time and is to be found in the current waste management documents produced by national government, and which form the basis of proposed future regulatory requirements with respect to medical waste treatment and disposal. As such we have considered the misunderstanding from the oldest source to the most recent: (a) The Minimum Requirements for the Handling, Classification and Disposal of Hazardous Waste (Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, 2nd edition, 1998) Guideline document Paragraph 9.4.1 stipulates that “medical waste must be incinerated, since the Human Tissue Act requires that all human parts be incinerated”. (b) The National Waste Management Strategy (Version D, 15 October 1999) Paragraph 11.1.5 “medical waste generators will be required to … sort their waste to ensure that only the infectious waste, which must be incinerated, (as required by the Human Tissue Act) is collected and subsequently treated”. (c) Action plan for Waste Treatment and Disposal (Version C, 15 September 1999, Part of the National Waste Management Strategy Series) Paragraph 1.1.1 “The majority of operating incinerators in South Africa are used for treatment of infectious medical waste, as stipulated in the Human Tissue Act”. Paragraph 1.3 listed as a priority initiative for the development of guidelines for the safe management of medical waste by 2001, will include guidelines for the separation of waste at source into infectious waste which requires incineration (according to the Human Tissue Act) and non hazardous medical waste that can be disposed of by alternate methods. Furthermore, and although not specifically referring to the alleged requirements of the Human Tissue Act, the White Paper on Integrated Pollution and Waste Management for South Africa (GNR227, GG20978 of 17 March 2000) and the Proposed Regulations for the Control of Environmental Conditions Constituting a Danger to Health or a Nuisance in terms of the Health Act 63 of 1977 (GNR21, GG20796 of 14 January 2000) appear to perpetuate the misunderstanding by highlighting proposed medical waste treatment procedures as being founded upon a need to incinerate. From a careful reading of the Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 and regulations promulgated in terms thereof, no stipulation cab be found that “medical waste” must be incinerated. In fact the Act does not make use of the term “medical waste”, but rather describes what have traditionally been considered to be its constituents, namely blood and tissue. The Act limits the definition of “blood” to human blood (Section 1), and defines “tissue” as: “(a) (b) any human tissue, including any flesh, bone, organ, gland or body fluid, but excluding any blood or gamete; and any device or object implanted before the death of any person by a medical practitioner or dentist in the body of such person”. (Section 1) The following provisions from the Act appear, to be the only provisions that deal with what is now commonly known as medical waste: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) An inspector of anatomy may remove and bury the remains of human body or tissue from any premises inspected if he deems it advisable (Section 31(1)(g)). The Minister of Health has authority to make regulations regarding the disposal, otherwise than in terms of Section 31(1)(g), of human bodies and tissue no longer required for any purposes referred to in Section 4(1) (Section 37(1)(a)). The Minister may further make regulations regarding the conditions for the disposal, otherwise than in accordance with Section 31(1)(g) of tissue or gametes no longer required for any of the purposes referred to in Sections 4(1) or 19, as the case may be (Section 37(1)(c)(iii)). The Minister may make regulations regarding the regulation and control of the disposal of human bodies handed over to institutions in terms of Section 12(1) and may furthermore make regulations with respect to the disposal of blood withdrawn or imported blood (Section 37(1)(e)(ii) and (iv)). Finally where tissue, blood, blood product or gametes has in the opinion of the Director-General been imported contrary to the provisions of Section 25 of the Act or the conditions of a permit issued under that Section, the Director-General may order the importer concerned to destroy the blood, alternatively that the blood be forfeited to the State, and the Director-General can then dispose of it in such a manner as she or he deems fit (Section 26(1) and (2)). Consequently the Act itself gives no clear directive to incinerate any medical waste, infectious or otherwise. At best there is an indication that blood must be destroyed, although no stipulation is given with respect to the technology which must be used. Arguably this in fact constitutes the exception rather than the rule to the Act, given the context of Section 31(1)(g)) which requires that the inspector is to remove and bury the remains of a human body or tissue. With respect to the powers the Minister has been given to create regulations regarding the disposal of human bodies or tissue, the only regulation of any relevance that we were able to find were the general regulations, namely the Regulations in terms of the Human Tissue Act (GNR2876, GG12234 of 29 December 1989). Regulation 2 is headed “Disposal of bodies and tissue” and stipulates: “Subject to the provisions of Section 31(1)(g) of the Act and any other law relating to the disposal of a human body or tissue, an institution which or a person who has, in terms of any provision of the Act, obtained a human body or tissue, and no longer requires such body or tissue or any part thereof for any of the purposes referred to in Section 4(1) of the Act shall– (a) bury or cause to be buried such body or tissue or such part thereof; and (b) enter in the register referred to in Regulation 3, the date, place and manner of such burial”. The regulation therefore stipulates burial of tissue, and does not require incineration. It is at this stage therefore not clear where or how the misunderstanding of the Act originated, and why it has seemingly been perpetuated in subsequent waste guidelines, national policy and proposed regulations. 2.2 Medical waste and current waste management laws In light of the fact that there is seemingly no specific and direct legal requirement that medical waste be incinerated, it needs to be considered whether incineration must be performed in terms of any other waste management law currently having application in this country. The principle definition of “waste” and the one having relevance in the context of this opinion, is contained in the Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989 and specific waste regulations promulgated in terms thereof (see Section 1 of the Act and GN1986, GG12703 of 24 August 1990). Medical waste does, in our opinion, fall within the ambit of this definition. “Disposal site” also has relevance, and is once again defined in the Environment Conservation Act as “a site used for the accumulation of waste for the purposes of disposing or treatment of such waste” (Section 1). Medical waste would fall within this definition given that it is being disposed of whether through treatment or otherwise. These definitions are of relevance given that the Environment Conservation Act stipulates that all waste is to be disposed of at a disposal site for which a permit has been issued or in terms of a manner or by means of a facility or method and subject to such conditions as the Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism may have prescribed in regulations (Section 20(6)). No regulations have been prescribed by the Minister with respect to the disposal of medical waste to date. However the form of technology to be used for medical waste disposal is probably indirectly influenced through the fact that medical waste must be disposed of at a site for which a permit has been issued by the Minister of Water Affairs and Forestry. This permit is issued in terms of Section 20(1) of the Environment Conservation Act and allows the Minister to issue a permit subject to such conditions as he or she may deem fit (Section 20(1)(a)). The principal grounds used by the Minister for issuing permits and imposing conditions are set out in the three guideline documents published by the Department, the most recent edition having been published in 1998. Of relevance to this opinion is the guideline document dealing with the Minimum Requirements for the Handling, Classification and Disposal of Hazardous Waste. As indicated these guidelines specifically, although incorrectly in our opinion, stipulate that medical waste must be incinerated as a requirement of the Human Tissue Act. Despite this error, the fact remains that the Minister will not issue a permit to a site to landfill medical waste unless and until it has either been sterilised or incinerated (paragraph 9.4.1, page 9-5). Although not considered in detail for this opinion, it should be borne in mind that this may expose the Department to legal challenge on the basis that its refusal to allow medical waste landfilling is based on an erroneous interpretation of the Human Tissue Act. If no landfill is permitted to take anything but incinerated medical waste ash or sterilised medical waste, then the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry is indirectly stipulating which technology may be used for the disposal of medical waste given that it will be necessary to landfill the waste in whatever form at a certain stage in the treatment process. The Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 45 of 1965 may also indirectly influence the use of incineration. Once again no clear reference is made to medical waste incineration although item 39 to the Second Schedule to the Act lists waste incineration processes as being Scheduled processes requiring a certificate. Guidelines for medical waste incineration have been drawn up. This position must also now be tested against the principles set out in Section 2 of the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998. This is in light of the fact that these principles apply to the actions of all organs of state and: (a) (b) serve as guidelines by reference to which any organ of state must exercise any function when taking any decision in terms of any statutory provision concerning the protection of the environment; and guide the interpretation, administration and implementation of any law concerned with the protection or management of the environment (Section 2(1)(c) and (e)). Although none of the approximately twenty principles directly discusses the acceptable form of treatment and disposal for medical waste, several of the principles will influence the validity of the current stance taken by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry with respect to the issuing of disposal permits, (and thereby its influence over medical waste disposal), and any future laws or standards emanating from any other government department which endeavour to regulate this subject. The following are some of the more relevant principles which may have a direct influence: (a) Included in the consideration of whether sustainable development is being applied, authorities must ascertain whether waste is being disposed of in a responsible manner (Section 2(4)(a)(iv)). As such it will need to be determined what constitutes responsible disposal with respect to medical waste. Some indication is highlighted in the principles which follow. (b) Government agencies must endeavor to ensure that pollution and degradation of the environment are avoided, or where it cannot be altogether avoided are minimised and remedied, and further negative impacts on the environment and on people’s environmental rights must be anticipated and prevented or at the very least minimised and remedied (Section 2(4)(a)(i) and (viii)). As such medical waste treatment technology must be such that it must have no impact on human health or the environment or, if this is not realistic, must have the least impact possible, with the latter position only being acceptable if any harm which is caused is remedied. Given the current concerns with respect to the emissions from incineration, this principle may play a significant role in the selection of the most appropriate treatment technology. (c) Supporting the above principle is the principle that a risk averse or cautious approach is applied, which takes into the limits of current knowledge about the consequences of decisions and actions (Section 2(4)(a)(vii)). This principle, also known as the precautionary principle, suggests that where the environmental impact of a proposed project is not fully understood due to the lack of information or limits of current science or technology, decision takers should err on the side of caution and refuse to allow the waste treatment methods. This would clearly have a direct bearing on any alternate medical waste treatment methods, where the precise impacts on the environment of the technology are not fully known or understood. (d) All of the aforementioned principles must also be measured against the overarching environmental management standard set out as a principle in the National Environmental Management Act, namely the Best Practicable Environmental Option standard (Section 2(4)(b)). The Act defines the standard as “the option that provides the most benefit or causes the least damage to the environment as a whole, at a cost acceptable to society in the long term as well as in the short term (Section 1(1)). Although this principle requires additional interpretation, the simple meaning of the term indicates that in the event that incineration, micro-waving or any other proposed medical waste treatment does not amount to the Best Practicable Environmental Option, it should not be allowed. (e) There are several social justice principles which will also need to be taken into account. These have relevance insofar as no new medical waste treatment plant should be allowed unless the interested and affected public have had an opportunity to voice their concerns. These principles include the environmental justice principle whereby adverse environmental impacts must not be distributed in such a manner as to unfairly discriminate to any person, particularly vulnerable and disadvantaged persons (Section 2(4)(c)). Moreover the principles require that decisions must take into account the interests, needs and values of all interested and affected parties and that the social, economic and environmental impacts of activities, including disadvantages and benefits, must be considered, assessed and evaluated, and the decisions taken must be appropriate in light of the conclusions reached (Sections 2(4)(h) and (i)). Very importantly the principles stipulate that decisions must be taken in an open and transparent manner (Section 2(4)(k)). In summary therefore any decision with respect to the appropriate form of medical waste treatment must, at the very least, take all of the above into account. There is however, in our opinion, currently no clear legal directive on the appropriate method for disposal of medical waste. 3 FUTURE DIRECTIONS As indicated in the Introduction and as will be highlighted below, the current policy and strategy documents do not give any specific indication on the acceptable form of treatment, save to apparently continue the misunderstanding surrounding the Human Tissue Act. Besides the principles contained in the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 having overarching environmental management relevance, the following will play a role with respect to medical waste disposal: The White Paper on Integrated Pollution and Waste Management for South Africa (GNR227, GG20978 of 17 March 2000) The National Waste Management Strategy (Version D, 5 October 1999) The proposed National Waste Management Act, and its regulations. The proposed regulations in terms of the National Waste Management Strategy. The Proposed Regulations for the Control of Environmental Conditions constituting a Danger to Health or a Nuisance in terms of the Health Act 63 of 1977 (GNR21, GG20796 of 14 January 2000). 3.1 The White Paper on Integrated Pollution and Waste Management for South Africa The White Paper recognises that waste disposal sites containing medical waste may result in land pollution problems (paragraph 3.3). As such the White Paper highlights as one of its strategic goals, in dealing with the effective institutional framework and legislation, to develop and implement regulations and guidelines for the safe management of medical waste in partnership with the Department of Health (paragraph 5.2.1). As such it would appear that medical waste regulations will be developed through the partnership between the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism and the Department of Health. This makes the proposed regulations in terms of the Health Act discussed below (at 3.3) particularly important given that an entire chapter has been dedicated to medical waste. A second strategic goal, regarding pollution prevention, waste minimisation, impact management and remediation has as some of its short term deliverables the following: (a) (b) (c) To develop a classification system for medical waste facilities, including incineration and alternative treatment technologies. To complete a plan for a system of medical waste treatment plants, and thereafter establish additional medical waste treatment facilities to be operated in accordance with this plan. To develop a revised air emissions standard for waste incineration facilities that will consider international standards and South African conditions, and be graded according to the size of the facilities and the type of waste incinerated. (paragraph 5.2.2) Points (a) and (b) above have direct relevance to medical waste and importantly indicate that government intends allowing such waste to be treated both by way of incineration and through alternative treatment technologies. As such, and contrary to what has been suggested in some quarters, it would not appear that incineration of medical waste is to be legally discontinued. Whether, as will be discussed under the National Waste Management Strategy below, the support for incineration remains due to misunderstanding of the Human Tissue Act, or whether national government has determined that it constitutes the Best Practicable Environmental Option for medical waste, remains to be determined. Encouragingly what also comes out of the White Paper, and as set out in point (b) above, is that national government will support the establishment and operation of additional medical waste treatment facilities. Although the White Paper is not law per se, it may arguably be used to compel government to comply with its own policy should it at any stage refuse to assist, on unreasonable grounds, with the Compass proposal to establish a further medical waste treatment facility. Point (c) above is of relevance as although not directly referring to medical waste, it is likely that one of the revised air emission standards for incineration will include medical waste treatment facilities. Importantly, in conducting this review of standards, national government intends taking into account international standards as well as South African conditions. 3.2 The National Waste Management Strategy The National Waste Management Strategy provides practical guidelines and steps towards giving effect to the White Paper on Integrated Pollution and Waste Management. With respect to medical waste the following is of relevance: (a) National government was supposed to develop guidelines and strategies before the end of 2000 to assist provincial governments to plan for management of medical waste (paragraph 7.1.5). These guidelines were to stipulate that medical waste must be sorted into general and hazardous waste, and that hazardous waste must be further separated into biological and chemical wastes, infectious wastes, and materials that have come into contact with infectious matter. The deadline for implementation of the guidelines for medical waste was 2001. Provincial plans were to be submitted by 2003 for urban areas and 2007 for rural areas (paragraph 7.1.5). None of this, to the best of our knowledge has occurred to date. (b) Recycling of medical waste is not seen to be viable due to the potential health risks. Recycling will only be viewed as a longer term objective (paragraph 10.1.5). (c) With respect to collection and transportation of medical waste, sorting is required (paragraph 7.1.5). “Medical waste generators will be required to … sort their waste to ensure that only infectious waste, which must be incinerated (as required by the Human Tissue Act) is collected and subsequently treated” (paragraph 11.1.5). The issues which arise form the aforementioned statement are as follows: (d) (i) The statement indicates that only infectious waste may be incinerated. No clear description of what “infectious waste” will entail is given. (ii) As highlighted separately in this paper, the reference to the Human Tissue Act is, in our opinion, wrong. (iii) Paragraph 11.1.5 goes on to add that “it will be the responsibility of the medical waste generator to ensure safe destruction and / or disposal of their waste. As such the onus is placed on the hospitals, clinics, doctors etc to ensure that their medical waste is safely destroyed and disposed of. This is in line with the cradle-to-grave principle applying to all waste streams. With respect to treatment the National Waste Management Strategy envisages that it will reduce the amount of medical waste that requires treatment. It adds that as a priority medical waste incinerators currently in operation must be upgraded to comply with revised standards or decommissioned and replaced by new facilities (paragraph 12.1.5). Although raised as a priority issue, it must be remembered that to date no revised medical waste treatment standards have been established. This once again reinforces government’s intention to maintain incineration as the principal form of medical waste treatment. Should co-ordinated planning between the provinces find that large regionally based facilities are more economically viable than a large number of small operating plants, the establishment of large regionally based facilities will be promoted (paragraph 12.1). The strategy envisages that facilities that comply with the revised standards were to have been in operation by 2002, and the collection and the treatment system will be implemented in the rural areas by 2008. The time schedule given for the closure of medical waste incinerators not meeting new air emission standards, and for the planning and establishment of modern facilities in urban areas was to have been initiated during 2000, and completed, as stated above, by 2002. (e) Finally, with respect to disposal, the National Waste Management Strategy envisages medical waste requiring treatment followed by disposal of ash or other residues at a permitted waste disposal site. “Disposal of unsterilised infectious medical waste to landfill will not be allowed” (paragraph 13.1.5). Importantly this statement once again indicates that incineration will seemingly be the preferred technology, although sterilisation and other treatment methods will be allowed. (f) One of the documents forming part of the National Waste Management Strategy is the Action Plan for Waste Treatment and Disposal. This document in essence repeats what has been summarised above under the National Waste Management Strategy but does make certain additional comments which may have relevance: It suggests that medical waste incineration was included in the Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 45 of 1965 for the first time in 1993 / 1994. Although an air emission standard and incineration procedure for medical waste was prepared, these are merely guidelines and do not form part of the Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act unless incorporated as conditions in a scheduled process certificate issued by the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. From a consideration of this Act, we can find no specific reference to medical waste incineration. Item 39 of the Schedule to the Act listing the processes requiring a certificate refers to “waste incineration processes”, although once again no specific reference is given to medical waste. Despite the above, the document adds that as none of the medical waste incineration guidelines could be met by any of the incinerators in South Africa, government took the following decisions: By December 2001 all existing incinerators were to have been upgraded or replaced to meet the required two stage incineration temperatures and resident time. New incinerators, with a capacity of less than 1 000 kgs an hour, must operate at the required temperatures and resident time. If the emissions standards cannot be met, an acceptable dispersion model may be used to determine whether the incinerator is acceptably located. All incinerators with a capacity of more than 1 000 kgs an hour must be fitted with pollution control equipment. (paragraph 1.2.3) This document also gives more direction with respect to revised air emission standards, and indicates that these were to have been finalised by the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism by December 2001 (paragraph 3.4). As has been referred to above, the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism in collaboration with the Department of Health will produce medical waste treatment guidelines. In taking into account international standards, this document suggests, by way of example, making use of the SABS Code of Practice 0248 which is based on the Canadian guidelines, as a starting point for the development of an improved system of separation of infectious waste from non-infectious waste (paragraph 3.5). The proposed guidelines will apparently look to removing non-hazardous waste from the incineration process to reduce incinerator emissions and costs for medical institutions. The guidelines will also introduce standardisation of medical waste containers and labelling. Very importantly for this project, the guidelines will consider alternative technologies for medical waste treatment, and specifically refers to microwaving, autoclaving or other appropriate technologies. The guidelines will be provided on their acceptability and feasibility for replacing or supplementing incineration technology that is still common in South Africa (paragraph 3.5.1). Finally, the guidelines aim to reduce air emission problems by giving consideration to restricting the use of halogenated plastics, particularly polyvinyl chloride, in medical equipment and waste containers that are incinerated (paragraph 3.5.1). 3.3 Proposed Regulations for the Control of Environmental Conditions Constituting a Danger to Health or a Nuisance in terms of the Health Act 63 of 1977 These draft regulations were first published on 14 January 2000. To date no further indication has been given as to whether they will be passed and implemented. The proposed regulations contain a separate chapter on the Handling and Disposal of Medical Waste (Chapter 6). A proposed definition for “medical waste” is given. The definition is long, and as such will not be repeated here. However it envisages five classes of medical waste namely: Class A – Anatomical waste This includes human and animal anatomical waste. Class B – Infectious non-anatomical waste. Class C – Sharps and similar waste. This lists any clinical item capable of causing a cut or puncture. Class D – Pharmaceutical and genotoxic chemical waste. Class E – Radioactive waste. Which must be disposed of in accordance with the Nuclear Energy Act 131 of 1993. (Regulation 1(1)) In light of the definition of “anatomical waste” referring to “biomedical material” it is also useful to consider the proposed definition for this latter term: “(a) (b) (c) Human and animal anatomical material, such as tissue, organs, body parts, products of conception and animal carcasses; Non-anatomical human and animal material, which is deemed to be blood, body fluids, extracted teeth, nail clippings and hair; Medical equipment such as blood bags, intravenous fluid containers or tubes, colostomy or catheter bags, bandaging, blood collection tubes, medication viles and ampoules, microscopic slides and (d) other laboratory glass, injection syringes and needles, surgical blades and any other clinical items capable of causing a cut or puncture or injections; human or animal vaccines, pharmaceutical products such as drugs and medicines, and chemical compounds that are genotoxic”. (Regulation 1(1)) Given the chapter heading referring to “Disposal of Medical Waste”, it would be reasonable to expect the chapter to describe the method for disposal of such wastes. Regulation 18 is headed “Duties of Generators, Transporters and Disposers of Medical Waste”. It suggests, although not very clearly, three apparent disposal methods: Disposal is to take place in accordance with this chapter, subject to the provisions of the Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989 and any other applicable legislation (Regulation 18(1)). The activity of disposing is to be carried out in such a way that medical waste generated does not cause a nuisance or a health or safety hazard for any handler of the waste or any other person or the environment in general (Regulation 18(2)). (Note that a specific definition for “nuisance” is proposed although no definition of “a health or safety hazard” is given. Presumably the latter term would be determined from other appropriate legislation.) A local authority may with provincial consent (presumably from the appropriate provincial health department and environmental department), allow a person to dispose of medical waste in any other acceptable manner provided the medical waste method of disposal does not constitute a nuisance or a health or safety hazard for any handler thereof or any other person or the environment in general (Regulation 18(3)). What is clear therefore is that although a specific form of treatment is not prescribed, the regulations will allow for disposal of medical waste by way of any technology or treatment method provided it does not cause a nuisance or a health or safety hazard to humans or to the environment in general. Furthermore a local authority can, with the permission of provincial government, allow an alternate medical waste disposal method. The only other indication of the method to be used is prescribed in proposed Regulation 19(5) which indicates that an incinerator or incineration process must comply with the prescriptions of the local authority and all relevant legislation, some of which it lists, in order to deal with waste having a wide variation of burning characteristics, ranging from highly volatile and high calorific value plastics to high water content material such as placentae. Therefore although not stipulating that incineration must be used, the proposed Regulations clearly envisage incineration of medical waste continuing. 4 CONCLUSION Although the current requirement of various regulatory authorities that medical waste must be incinerated is, based on a misunderstanding of the Human Tissues Act, this method can probably be enforced through the waste disposal permit procedure issued by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. Whether it is the Best Practicable Environmental Option or not is an issue which remains outstanding and needs to be tested against the environmental principles set out in Section 2 of the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998. What is clear is that the future waste management laws, which are in the process of being formulated and given effect, clearly still envisage incineration as a viable form of medical waste treatment and disposal. Moreover the future direction indicates that other forms of treatment technology will be allowed, once again provided theycomply with the prevailing environmental standards, and, in our view, with the Best Practicable Environmental Option Standard. The National Waste Management Strategy, although not necessarily binding, does assist with the practical requirements for medical waste treatment. However government is apparently way behind schedule on implementing the strategy, and appears to have missed most of the deadlines set in the strategy. Whether this means there is to be a shift in the strategy with respect to medical waste remains to be seen. The National Waste Management Act, which is currently being drafted will hopefully clarify the position. Shepstone & Wylie Ian Sampson Partner, Environmental & Sustainability Law Tel: (031) 566 – 8260 / Fax: (031) 566-2097 / Cell: 082 775 3720