Are minds are bodies distinct kinds of substances

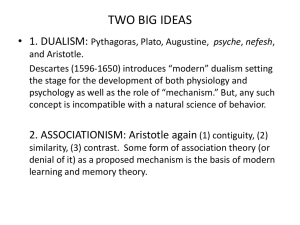

advertisement

AMEY U4423598 A211/03 Are minds are bodies distinct kinds of substances? The idea that minds and bodies are two distinct substances is famously associated with Descartes. The conclusion that the mind and body are separate can be reached by considering the view point of a radical sceptic. All the information we have about the world is bought to us through our senses. They are the only way we can receive empirical knowledge, and all our methods of checking their information also rely on them. Also, we know they can be deceived and often are. The railways lines that seem to meet at a point somewhere on the horizon do not meet at all. By making further observations, by walking down the track or thinking about how train run we can easily tell that the appearance of the lines meeting is only an optical illusion, and we dismiss it. Anomalous results are discarded to make the most coherent view of our world possible. But the possibility remains that if we could be deceived in one respect, that we could be deceived in many. In fact, Descartes suggested, we could be deceived in all our perceptions. There is no proof that all our perceptions are provided to us by an ‘evil genius’, and that the earth, colours, figures, sound and all other external things are nought but the illusions and dreams of which this genius has availed himself in order to lay traps for my credulity. (Descartes in Book 5 p158). 1 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 Faced with this uncertainty Descartes falls back to the cogito, his famous statement of the one thing we can be sure of: ‘I am, I exist, is necessarily true each time I pronounce it, or that I mentally conceive it.’ (ibid. p161). This is where dualism starts. While the existence of your mind is safeguarded by the cogito, your body is not. Even your knowledge of your body comes through your senses, and so can be doubted. The mind’s existence can be proved a priori, before reference to the outside world, the body cannot. Adding the reasonable premise that concepts whose existence must be proved separately are separate concepts, a divide is drawn between the mind and the body. Descartes did go on to argue for the existence of his body, based on his ‘clear and distinct’ (ibid. p175) impression of it. However, he perceives the distinction between his mind and body just as distinctly. In meditation VI Descartes describes more exactly how this distinction manifests itself. The mind is a substance the essence of which is to think. Substance in this instance, and throughout this essay, will be taken to have Descartes’ meaning as ‘a thing which so exists that it needs no other thing in order to exist.’ (ibid. p23). The essence of the mind-substance, Descartes argues, is thought. To have a mind without thought is incoherent, thought is what makes a mind a mind. If a thing has thought then it is a mind, if it does not then it is not a mind. The essence of the body-substance and of all physical things, Descartes says, is physical extension. To have extension makes something a physical object, and an object without extension cannot be a physical object at all. To this framework of two substances must be added further observations of the appearance of the world. For instance, my experience is available to me in a unique 2 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 way. I sense my pain in a way that no-one else can, and no-one else can sense my pain. Also this pain is directly felt, not just observed. In the film Terminator 2, the character of the robotic assassin describes ‘I sense injuries. The data could be called pain.’ (Terminator 2, 1991) The Terminator’s passive experience is not the experience of people. Pain hurts! This means that minds must have a distinctive link with one body and one body alone, and that raises the question, what form can this link take? While Descartes gives little description of the nature of the mind-substance, it is clear that it is not physically extended. How something without a physical presence can interact with the physical world was made clear neither by Descartes, who simply asserted the link, nor by subsequent thinkers. Both the necessity for this link and its mysteriousness are inherent in a dualist theory, and extends in both directions: not only must pain and sense information somehow reach my mind from the physical world, but my responses must reach the world. Everyday experience seems to show that when I decide to move my arm, my arm moves. Information flows to and from the mind, somehow bridging the physical / mental divide. The dualist divide also comes under fire in a less rigorous way from the principle of Ockham’s razor. It is a principle rather than a hard and fast rule, but can be expressed as ‘don’t multiply entities beyond necessity’ (Thinking from A to Z, p97). In this case, materialists argue, there is no need for a second substance when the material world is all that is necessary. Materialism has no problem with associating pain and feelings especially with one body – your brain is only attached to one body, so that body’s pain is all it will ever feel. The links between the brain and body are readily examinable to anyone with a corpse and a scalpel. The issue then becomes, can 3 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 collections of atoms in the material world really account for our subjective experience of the world? One of the greatest inconsistencies levelled at material monism is associated with the materialist treatment of qualia. Qualia are our sense experience; the colour red, the smell of a cooked pizza, the texture of paper between your fingers are all qualia, they are the sensations that make up your view of the world around you. They are subjective, they are your own experiences and as such it seems at first as though noone else can experience them as you do. There appears to be no guarantee that what I see as red you see as blue, although you attach the label ‘red’ to it, just as I do. We would both agree that the top traffic light is ‘red’, although the sensations we have are different. Looking more closely, though, this form of inversion is not so simple. There are various aspects of colours which everyone agrees on but which preclude this form of inversion. For instance, you cannot have a greenish-red colour. You can have reddishyellow, and yellow-green, but not greenish-red. That’s universally acknowledged, and may seem like an arbitrary limitation until you consider the wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation that cause what we call colour. Red is a lower wavelength than yellow which in turn is a lower wavelength than green. So instantly you can see that greenish-red isn’t possible, both of those colours fade into yellow first. So imagining a person who’s see red as blue but is otherwise identical suddenly problem problematic - he should have no problem seeing a greenish-red, for him it would be greenish-blue but physically it cannot happen. Conversely he should be able to imagine a bluey-orange colour with no difficulty, and he may be puzzled as to why 4 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 there are no instances of it in nature. Qualia and the material world are much more closely linked than dualism can allow for; in dualism, where colours exist ‘freely’ in the mind artificial explanations are needed for the absence of greenish-red and other, similar, limitations. A further criticism of materialism is based on how these qualia could exist within a brain. This is demonstrated by the China Brain thought experiment. This experiment imagines that the individual people of China are persuaded to act as neurones. Each can signal to others around him via radio in a manner completely analogous to neurones firing. In fact, the entire arrangement in entirely equivalent to the arrangement of neurones in the brain and can then be attached to a dummy that provides sense input and moves like a person. Combine this set-up with the materialist premise that minds are purely physical, and it follows that the China brain we have created should be able to think and feel in exactly the way we do, it should be entirely equivalent to a person. It should be able to know the colour red and get angry, confused and happy just as we do. However, the argument runs, as the China brain clearly does not have any knowledge of red, or the smell of a rose or any other quale, the materialist view must be incomplete. The problem here is with the premise that qualia cannot exist within this collection of people. Qualia are no less likely to exist with a collection of people than they are to exist within a collection of neurones, so to deny that they exist in the China Brain is to beg the question. To put that question explicitly: can sense experience exist in a wholly material system? To argue that qualia can exist in solely a brain seems to leave no way of denying that qualia could not also exist in the China Brain, a Star Trek 5 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 plasma cloud or a computer system. Personally, this seems to me to be the next logical step in the long history of showing that humans are nothing special. In the time of Aristotle it was thought we lived at the centre of the universe and were a species created in God’s image. Newton and Darwin respectively showed that neither our planet nor our species was anything other than an unimportant example of the wider workings of the universe. The desire to hold our minds as something special seems to spring from that same egotism and, while there is no empirical evidence to show how ethereal concepts like qualia, self-consciousness, guilt or grief could exist in a brain, the precedent for explanation is good. I have defended materialism against the China brain thought experiment and against the qualia inversion argument, and I have highlighted the problem of communication between the substances in dualism. But the first argument for dualism remains, the foundation, the bedrock, the cogito. It has been claimed that Descartes relied on an un-stated premise in his famous axiom, namely that thoughts require a thinker. The ‘I’ of ‘I am, I exist’ then becomes the very thing Descartes is trying to prove, and hence that he is begging the question. A better rendering, it is suggested, is ‘there are thoughts’. Simply by using fewer words this takes a step away from contention, and this new rendering gives new possibilities. As thoughts are less mysterious than an ‘I’ they do not necessarily need to dwell in a different substance; they could be housed in a brain, and might even eventually be open to investigation by science. Certainly Descartes has succinctly put an incredible and undeniable certainty, but the exactly form of that certainty must be carefully examined, and the consequences of it are by no means clear. 6 AMEY U4423598 A211/03 While both materialism and dualism have problems that need to be overcome it seems that progress can only be reasonably made to resolve the materialist dilemmas. Because of that, and the intuitive lure of Ockham’s razor, I conclude that minds and bodies are not distinct substances. Word Count: 1870 Bibliography Nigel Warburton (2000) Thinking from A to Z, Routledge Robert Wilkinson (1999) Minds and bodies, The Open University James Cameron (1991) Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Simon Blackburn (1999) Think, Oxford Univeristy Press Martin Hollis (1997) Invitation to Philosophy, Blackwell Publishing 7