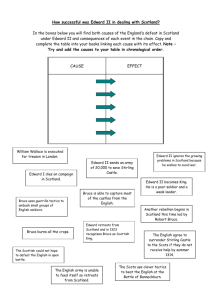

The rise and triumph of Robert Bruce sources bank

advertisement

The rise and triumph of Robert Bruce Sources 1 The ambitions of Robert Bruce From For the lion: a history of the Scottish Wars of Independence 1296-1357, Raymond Campbell Paterson, 1996. For Robert of Carrick the rapidly changing political situation was alarming. He was clearly alienated from the Comyn leadership of the national cause, and seems to have played little part in the war since he was replaced as Guardian in 1300, only defending his own territories. The return of King John and his son Edward would obviously deprive him of any prospect or ruling Scotland. But in view of his own ambiguous conduct, and the continuing loyalty of his father to the English, he might be in danger of losing his parental inheritance in Annandale, or even the earldom of Carrick itself. With these fears at the front of his mind, the time had come for him to make his peace with Edward. From Scotland: the later Middle Ages, Ranald Nicholson, 1974. In October 1301 there was a report from France that ‘the king of France’s people have taken Sir John Balliol from the place where he was sent to reside by the pope to his castle in Picardy, and some people believe that the king of France will send him with a great force to Scotland as soon as possible’. Such a prospect was disquieting to at least one notable Scot. For two years after being dropped from the guardianship in 1300 Robert Bruce, the earl of Carrick had probably contented himself with defending his earldom against all outsiders, whether English or Scots. Yet neutrality would no longer suit his purposes when it seemed that a Balliol restoration was at hand. By February 1302 Bruce ‘yielded himself to the peace and will of King Edward I in the hope of receiving his mercy’. To what extent do the sources agree on the part played in the Wars of Independence by Robert Bruce, the earl of Carrick, between 1300 and 1302? (5) 2 From, For freedom alone: the Declaration of Arbroath 1320, Edward Cowan, 2008 Posterity has proved bewildered and embarrassed by Bruce’s changes of allegiance, words such as ‘traitor’, ‘betrayal’, ‘treachery’ and ‘turncoat’, to name but a few, coming uncomfortably to mind; but this is to misunderstand the circumstances and to misconstrue the period, let alone Bruce’s personal position. The changing of sides in fourteenthcentury Scotland can be more usefully compared to a football transfer or the recruitment of a boardroom director by one company from another, except that Bruce was acting from less selfish motives than those modern analogues. He always had to give priority to the interests of the family which, after all, had a valuable claim to the kingship. He was the head, the custodian and servant of the family, its privileges, rights, honours and obligations’. From In search of Scotland, Fiona Watson, 2001. We must accept that everyone believed that the question of Scotland was settled in 1305, at least in the short term. This helps to explain the reaction to Robert Bruce’s seizure of the throne early in 1306: from 1300 onwards the Bruce cause was effectively dead within Scottish politics. Added to this was the fact that, despite the earl of Carrick’s defection to Edward in 1302, the Comyns were clearly being rehabilitated into royal favour as part of the settlement of 1305. Edward made considerable efforts this time to involve sufficient key members of the Scottish political community in the government of their country to encourage loyalty to the new regime. Once again, Bruce was heading down a dead end in his plans to become king. 3 His conflict with and victory over Scottish opponents From The Chronicle of the Scottish nation, John of Fordun, 1370s. He (Bruce) humbly approached a certain noble, John Comyn, who was then the most powerful man in the country, and laid before him the cruel and endless tormenting of the people, and his own kind-hearted plan to bring this to an end. Robert gave John the choice of one of two courses: either that John should reign, and take unto himself the kingdom, forever granting to Robert all his own lands and possessions, or that all Robert’s possessions should come into the possession of John, while the kingdom would go to Robert. John was perfectly satisfied with the latter suggestion, and an agreement was made between them, by indentures with their seals attached. But John broke his word, and heedless of the sacredness of his oath, kept accusing Robert before the king of England, through messengers and letters. The aforesaid Robert, learning of John’s treachery, returned home, and a day was appointed for him and John to meet together at Dumfries. John Comyn was accused of treachery and he denied it. The evil speaker was stabbed and wounded in the church of the Friars. And the wounded man was laid behind the altar by the friars. On being asked by those around if he would live, he straightaway answered, ‘I can’. His enemies, on hearing this, gave him another wound as he died. 4 From The Scottish civil war: the Bruces and the Balliols and the war for control of Scotland, Michael Penman, 2002. It is very likely that Bruce’s canvassing support for his claim to the kingship had reached the point where he had to be sure either of Comyn’s neutrality or his vested interest. According to English chronicle sources, Bruce falsely accused Comyn of betrayal and carried out a premeditated plan to despatch Comyn before the high altar. By contrast, in Scottish chronicle accounts, Comyn was the ‘evil speaker’ and deserved to die in hot blood. In the immediate short term, Bruce’s sacrilegious murder cannot have been pre-arranged. The old personal animosities and frustrations of 1299 between these two ambitious lords must have simply come pouring out. At best, Robert could be said to have been forced by his precipitate actions to have put into premature motion already well laid plans. The rapid course of events over the next two months suggests that Robert immediately set his sights on Scone. From In the footsteps of Robert Bruce, Alan Young and Michael J Stead, 1999. The murder of John Comyn, acknowledged by both Scots and English as the most powerful man in the country, was a dramatic and important event in Scottish history, as well as in Robert Bruce’s career. It seems most probable that their bitter antagonisms of the past – they had literally come to blows at a baronial council at Peebles in 1299 – were instantly revived and, in a heated argument, mutual charges of treachery were made. It is unlikely that the murder was premeditated. Bruce struck Comyn with a dagger and his men attacked him with swords. The fact that Bruce was enthroned king of Scots only six weeks after the murder reveals that some preliminary planning had been carried out. The murder undoubtedly accelerated plans that Bruce was already preparing with Wlliam Lamberton, the bishop of St Andrews, and Robert Wishart, the bishop of Glasgow. From Robert Bruce and the community of the realm of Scotland, G W S Barrow, 2005. It is contrary to everything we know of Bruce’s character that he should have called Comyn to the Greyfriars’ church with the secret intention of killing him. The place of the meeting and the kiss – though it was not the kiss of peace – with which the two men greeted each other all suggest that Bruce meant only to put some plan to Comyn. No doubt Bruce’s intention was to take the throne himself, and give his estates to Comyn. Comyn can hardly be blamed for refusing. Comyn would have none of it. It may be that Comyn called Bruce a traitor. It seems certain that Bruce struck at Comyn with a dagger. At this, Bruce’s companions attacked him with their swords. Mortally wounded he was left for dead. John Comyn’s uncle, rushing to defend his nephew, was killed by a blow on the head from the sword of Christopher Seton. Soon the town was in uproar, the Scots flocking to Bruce’s support. It was then reported that Comyn was still alive. The Franciscan friars had carried him into the vestry to treat his wounds and Administer the last sacrament. 5 From The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough Bruce, fearing Comyn, who was powerful and faithful to the English king, and knowing he could be stopped by him in his ambition to be king, sent to him asking, Would he please come to him at Dumfries to deal with certain business affecting them both. Comyn, suspecting nothing, came to him with a few men. When they were speaking together in turn, with words which seemed peaceful, suddenly, in a reversal and with different words, Bruce began to accuse him of betrayal, and that he had accused him to the king of England and had worsened his position to his harm. When Comyn spoke peaceably, Bruce did not wish to hear his speech, but, as he had conspired, struck him with his foot and sword and went away out. But Bruce’s men followed Comyn and cast him down on the paving before the altar, leaving him for dead. Robert Comyn, his uncle, ran to bring him help, but Christopher Seton met him, struck his head with a sword and he died. Bruce came out, saw John Comyn’s fine horse and mounted it, and his men mounted with him. They went to the castle and took it. Then some evil folk told him that Comyn still lived, for the friars had carried him down to the altar vestry, to treat him. By the tyrant’s order he was pulled out of the vestry and killed on the steps of the high altar. From In the footsteps of Robert Bruce, Alan Young and Michael J Stead, 1999. After initially friendly words Bruce turned on Comyn and accused him of treacherously reporting to Edward I that he, Bruce, was plotting against him. In a heated argument, mutual charges of treachery were made. It is unlikely that the murder was premeditated. Bruce struck Comyn with a dagger and his men attacked him with swords. Comyn’s uncle, Robert, was killed by Christopher Seton when he attempted to defend his nephew. According to both English and Scottish tradition, Comyn himself was mortally wounded, left for dead and finally killed later. In the circumstances of Anglo-Scottish politics at the time, it is most likely that the argument was about having the ear of the English king and his influence and backing. To what extent do the sources agree about what happened in the Greyfriars’ church in Dumfries in February 1306? (5) 6 Letter from Edward I to Pope Clement V, 1306 Robert Bruce has committed treason against his liege lord the king of England, to whom he owed homage and fealty, and has murdered John Comyn, lord of Badenoch in the church of the Friars minor in the town of Dumfries, beside the high altars, because the said John would not give assent to the treason which the said Robert planned to commit against the said king of England, that being to revive the war against him and make himself king of Scotland. How useful is the source in explaining why Bruce murdered John Comyn in 1306? (5) From In search of Scotland, Fiona Watson, 2001 Bruce’s actions in 1306 seem like those of a man with nothing to lose. Whatever prompted the meeting between these bitter rivals, Bruce and Comyn to meet in the Greyfriars church in Dumfries in February 1306, the end result – the murder of Comyn – forced Bruce to gamble everything, including the lives of his own family, in a make-or-break attempt on the Scottish throne. The timing was appalling, so soon after the end of the previous war, with the voluntary oaths of allegiance still in force. Add to that the brutal and sacrilegious murder of Scotland’s most important political figure and the actions of FebruaryMarch 1306 seem almost suicidal. The automatic opposition of the Comyns and their allies, as well as those who still saw John Balliol as the rightful king (and there were many), meant that there were precious few prepared to back the new king, either at his inauguration or in his army. How far does the source explain the opposition of many Scots to Robert Bruce? 7 (10) Charges to the pope against Robert Wishart, bishop of Glasgow. After the murder of John Comyn in the Greyfriars Church at Dumfries, the bishop gave neither sentence of excommunication nor exercised the office of bishop for the deed of such a murder and sacrilege, but behaved as one who approved of and agreed with it. Then after this, when the earl of Carrick by force of war wanted to make himself king, the bishop had made for him, and stored in his own wardrobe, the robes with which the earl had himself vested and attired on the day on which he wished to have himself called king of Scotland; and he sent this attire, together with a banner of the late king of Scotland, which he had long before hidden in his treasury, to the earl at the abbey of Scone before the day when he had himself called king of Scotland. Summoned to Berwick, he joined the earl of Carrick and stayed with him. And moreover the bishop went preaching through the land to make the folks rise against the king’s faith and peace, to maintain the estate of the earl, and preaching that it is good to fight the king of England as to go in God’s service to the Holy Land. The, having been given by the king wood to make the steeple of his cathedral church of Glasgow, the bishop had siege engines made of this wood to be mounted against the castles of the king and had them moved and set before Kirkintilloch Castle, which was in the king’s hands, and had missiles thrown from these engines at the castle and had it besieged until the castle was relieved by the king’s men who lifted the siege and burned the engines. From Robert Bruce: our most valiant prince, king and lord, Colm McNamee, 2006. Certainly there was nothing left to Robert now but further flight into the wilderness. It is impossible to imagine that he could avoid despair on taking to the heather after Methven and Strathtay. He had gambled and he had lost heavily. Whether he cursed his ambition for bringing ruin on his family and friends, he surely regretted whatever had transpired in the church at Dumfries, for it set in motion a chain of events that could now – it seemed – only end in death and disgrace. Working from the benefit of hindsight, commentators have tended to exaggerate such faint glimmers of hope as remained to him. Recovery from this desperate position was by no means inevitable, however; it was, rather, miraculous. 8 From Scotland: the later Middle Ages, Ranald Nicholson, 1974. It was probably only on his return to Carrick that Bruce learned the full measure of the disasters that had been inflicted upon his family and friends. If hitherto he had been merely self-seeking and ambitious, he was no longer so. His crown had been too dearly bought by the sacrifices of others. Ambition and chivalric adventure had ended in a tragedy that he was to redeem by identifying himself completely with the highest traditions of kingship and devotion to the cause of independence. Letter written by a Scot on the English side shortly after Loudoun Hill, 15 May 1307. I hear Bruce never had the good will of his own followers or of the people so much with him as now. It appears that God is with him, for he has destroyed King Edward’s power both among the English and Scots. The people believe that Bruce will carry all before him. I fully believe that if Bruce can get away to the north, he will find people all ready at his will more than ever, unless King Edward can send more troops. May it please God to prolong Edward’s life, for men say openly that when he is gone the victory will go to Bruce. How useful is the source in describing Bruce’s position following his return to the mainland in 1307? (5) A report from the sheriff of Banff to Edward II, possibly April 1308. Robert Bruce with his army came to the castle of Inverlochy and he caused that castle to be handed over to him by the deceit and treason of the men in the castle. The castle at Nairn is burned by the same Robert and the castle of Urquhart is lost. Moreover, Robert Bruce with his force besieged and strongly assaulted the castle of Elgin where sir Gilbert Glencairnie junior was. When a truce was made with sir Gilbert, he went to the castle of Banff where he fell ill and stayed in a certain manor house of mine for two nights. He burned the manor and all my grain, and hearing of the arrival of the earls of Buchan and Atholl, with all his force he moved to the Slioch, and destroyed a manor of mine next to my castle. How useful is this source in describing the tactics used by Bruce against his Scottish enemies? (5) 9 From In search of Scotland, (edited by Gordon Menzies),Fiona Watson, 2001. Bruce was lucky – one of the key attributes of a successful leader. Even before the death of the great warrior king Edward I in July 1307, he had been able to score a few small-scale points. But there is no doubt that the change of regime in England made a huge difference to King Robert’s cause. Those who were uncommitted to either the Comyn or the Balliol cause were free now to accept Bruce as their liege lord. Equally important, the new English king, Edward II, soon face internal political problems, partly as a result of England’s long-standing financial difficulties, but also as a result of his own incompetence. Bruce still faced considerable opposition within Scotland, but it was no longer united and fully supported by England. He tackled the Comyns first, attacking them in their heartlands in the north-east and sending the Comyn earl of Buchan into permanent exile in England. Slowly but surely each success had an increasing effect and the tide began to turn. From Independence and nationhood: Scotland 1306-1469, Alexander Grant, 1984. In the civil war, Robert I’s enemies in the north, the earls of Buchan and Ross and the lord of Argyll were supreme in their own provinces but relatively unimportant elsewhere. Moreover their territories were separated by the province of Moray, where there was no earl to organize any resistance to Robert I, and where the population had been prominent in the independence struggle since 1296. In Moray Robert appealed directly to the lesser men, who responded well, providing the bulk of his support at this time. The province also had great strategic importance: it gave Robert internal lines of communication from which to strike at each of his enemies in turn, making them defend their own lands and preventing them from uniting against him. Thus, although Robert I would have been outnumbered by his enemies’ full force, he was never confronted by more than a fraction of it. He was even able to send part of his army back to the south-west to deal with Galloway, the other main centre of opposition. 10 From Independence and nationhood: Scotland 1306-1469, Alexander Grant, 1984. The transformation of Robert I’s fortunes was largely due to the outstanding military skill he showed from 1307. He learned from his early defeats to forsake conventional warfare for guerrilla warfare, at which he proved a genius. His strategy was based on swift, small-scale operations in which he kept the initiative. He fought only on his own ground and preferably from ambush, he avoided major pitched battles, and he always dismantled rather than garrisoned strongholds which fell into his own hands. From The Scottish civil war: the Bruces and the Balliols and the war for control of Scotland, Michael Penman, 2002. The death of Edward I was a real watershed. Despite a testing apprenticeship in the English campaigns in Scotland of 1299-1304, the new king, Edward II, showed neither any real inclination or the necessary leadership skills to recover and reconquer the realm that once could have been his through marriage. Determined to keep down the unpopular costs of war (over and above the £100,000 or more of Italian banking debts he inherited from his father) and busy creating political crises at home, this Edward would make only a token show of force in Scotland in 1307, withdrawing before the summer was out and not returning for three years. Crucially this left the English occupation regime sorely undermanned and underpaid, dependent upon the ranks of Bruce’s Scottish enemies to fill the gaps in their garrisons and to be their eyes and ears in the localities in the full knowledge that they could do little to aid these nobles in any fight. Any of the above four sources could be used with the following questions. How far does the source explain Bruce’s successes against his Scottish enemies between 1307-1308? (10) OR How far does the source explain Bruce’s successes against his enemies in the years before Bannockburn? (10) THE ABOVE GRANT SOURCE: How far does the source illustrate Robert Bruce’s qualities as a military leader? (10) 11 A letter from the earl of Ross to Edward II, probably written November 1307. We heard of the movement of Robert Bruce towards Ross with a great force, and we had no power against him, but we called out our men and were ready for a fortnight with three thousand men at our expense on the borders of our earldom. Bruce would have destroyed them utterly if we had made no truce with him. May help come from you if it please you, for in you, Sire, is all our hope and trust. On no account would we have made a truce with him, but the men of Moray would not help us. We have no help except from our own men. John Macdougall of Lorn asks Edward II for help against Bruce, probably March 1308. Robert Bruce approached these parts by land and sea with 10,000 men they say, or 15,000. I have no more than 800 in my own pay whom I keep continually to guard the borders of my territory. The barons of Argyll give me no aid. Yet Bruce asked me for a truce, which I granted him for a short period, and I have got another similar truce until you send me help. Either of the above could be used to answer the following question(s): How useful is the source in explaining why Bruce was able to defeat his Scottish enemies? (5) To what extent do the sources agree on the problems facing Bruce’s enemies in the period 1307-1308? (5) 12 From In search of Scotland, (edited by Gordon Menzies),Fiona Watson, 2001. By 1309 Bruce had secured enough of Scotland to enable him to call his first parliament. This proved the ideal opportunity to begin the process of justifying to the world (and especially the pope) just why King Robert had taken the actions he had. Bruce had proved exceptional not just at guerrilla warfare but in the realm of propaganda, although we should also acknowledge his good fortune in maintaining a group of extremely gifted propagandists in his Chancery, the arm of government responsible for producing official documents. The so-called Declaration of the Clergy produced in 1309 laid down the foundations of many of the myths which still hold sway even today, including the assertion that John Balliol was an English puppet. From The Scottish civil war: the Bruces and the Balliols and the war for control of Scotland, Michael Penman, 2002. In the campaign to seize English-held burghs and castles, Robert I led the way bravely, for example, wading across the icy moat at Perth in January 1313 to be the first up the scaling ladder and over the walls. Bruce’s generals, too, made a name for themselves in their exploits with Douglas overwhelming Roxburgh castle in early 1314 just a few weeks before Randolph overran Edinburgh. Such was the Bruce momentum on this home front that by spring 1314 only the hugely symbolic garrisons at Stirling, Berwick and a few border castles held out. With little sign of a reply from Edward II, many ‘Balliol Scots’ decided to defect in the face of duress and threat to their lands, including the earls of Atholl and Strathearn, and Sir John Menteith. Bruce, still in search of support, reinstated them or their heirs. Others like Patrick, earl of March, purchased private truces on their borders to spare their lands from Bruce attack. 13 Bannockburn David Cornell, A kingdom cleared of castles: the role of the castle in the campaigns of Robert Bruce, Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXVII, 2, No 224, October 2008: The traditional view that the agreement for the relief of Stirling was of a year’s duration has convincingly been proved incorrect; Stirling was not besieged in 1313 but in the spring of 1314 after Edinburgh and Roxburgh had already fallen. When in late 1313 Edward II decided to undertake a Scottish campaign the following year, the objective was to seek out and destroy Bruce and his adherents. It was only when the English host had reached Northumberland that news was received of Stirling, this being as late as 27 May, 1314. The campaign was therefore not undertaken to relieve Stirling. Rather the siege began when the English host was already assembled and heading north, the siege being not of one year’s duration but a matter of weeks. From The chronicle of the Scottish people, John of Fordun, 1370s. The earl of Gloucester and a great many other English nobles were killed; a great many were drowned in the waters, and slaughtered in pitfalls. A great many of different ranks were cut off by many kinds of death. And many – a great many – nobles were taken prisoner, for whose ransom not only were the queen and other Scottish prisoners released from their dungeons, but even the Scots themselves were all enriched very much. Among those taken was John of Brittany, for whom the queen and Robert, bishop of Glasgow were exchanged. From that day forward, moreover, the whole land of Scotland not only rejoiced in victory over the English, but also overflowed with boundless wealth. How useful is the source in describing the rewards the battle of Bannockburn brought Bruce and the Scots? (5) NB Fordun writes ‘John of Brittany’, but it was the earl of Hereford who was exchanged for the Scottish prisoners. So you could substitute the earl of Hereford for John of Brittany if you use the source. 14 From Scotland: the story of a nation, (by Magnus Magnusson), Steve Boardman, 2000. I think the significance of Bannockburn has been exaggerated in the Scottish consciousness, but there is no doubt that it was hugely important in terms of its moral and political significance – the defeat of a major English army in open battle. It also, and perhaps more importantly, gave Bruce much greater control of his own kingdom: most of his former opponents now accommodated themselves with the new regime or went into exile as pensioners or retainers of the English crown. What Bannockburn did not do was deliver independence. The English realm could absorb one defeat; England could always generate another army which could reverse the effects of Bannockburn. Bannockburn was an important staging-post on the route to recognition of Scotland’s independence, but it was not the end of the road. From Independence and nationhood: Scotland 1306-1469, Alexander Grant, 1984. In the Anglo-Scottish war, Bannockburn was relatively unimportant; not for 14 years did the English recognize Scottish independence. The battle’s main impact was on the Scottish civil war. To most contemporaries it proved that God and right were on Robert I’s side. Also it made Robert I’s Scottish opponents recognize that his power in Scotland was now irrestistible, and that there was no chance of turning the tide again, even with English help. Most of them, realistically, accepted Robert I as king. To what extent do the two sources agree about the significance of the battle of Bannockburn? (5) From The wars of Scotland 1214-1371, Michael Brown, 2004. Bannockburn did not end the war against Edward II. It would be fourteen years before an English king would recognise Robert’s kingship. Though the battle added hugely to Bruce’s prestige, it did not give him and his family a secure title to the Scottish throne. However, Bannockburn was the end of one war. It was a decisive defeat for Robert’s Scottish enemies. The death in battle of John Comyn, the son of the lord slain in 1306, followed the demise of John, the earl of Buchan, and removed the last leader of the great house of Comyn in Scotland. 15 Continuing hostilities From In search of Scotland, (edited by Gordon Menzies),Fiona Watson, 2001. Bannockburn did not win the war for the simple reason that Edward II was not captured and thus continued to deny the Scots and their king any admission of their independence. This was a considerable failure, illustrated by the fact that, if anything, the battle prompted even greater military activity, even if it was not conducted within Scotland itself. The practice of invading over the border and extorting blackmail from the local inhabitants for the privilege of not being burnt out was now developed into a fine art in an attempt to force Edward to the negotiating table. Unfortunately for Bruce, the suffering of the area made little impact on the southern English government, although the lucrative nature of these raids undoubtedly helped the Scottish finances. From The Lanercost Chronicle, 1314. About 1 August Sir Edward Bruce, Sir James Douglas and other nobles of Scotland with knights and a large army, invaded England by way of Berwick and devastated by fire virtually the whole of Northumberland. They crossed into the bishopric of Durham, but there they did not burn much because the men of the bishopric paid them off from burning by a large sum of money. But the Scots took away booty in cattle, and men whom they could take prisoner, and so they crossed further into the earldom of Richmond, and perpetrated the same things there without anyone resisting. Almost all fled southwards except those who found refuge in the castles. How useful is this source in explaining the impact of the Scottish raids into northern England? (5) From The Chronicle of the Scottish people, by John of Fordun, 1370s. Edward Bruce entered Ireland with a mighty force in 1315, and having been set up as king there he destroyed the whole of Ulster and committed countless murders. The cause of this war was this: Edward was a very courageous and high-spirited man and would not dwell together with his brother in peace, unless he had half the kingdom for himself, and for this reason this war was stirred up in Ireland. How useful is the source in explaining why Robert Bruce sent an army to Ireland in 1315? (5) 16 From The Lanercost Chronicle, 1322. Robert Bruce plundered the monastery of Holm Cultram even though his father’s body was buried there, and then proceeded to lay waste and plunder Copeland, and so on to Furness. On his way to Furness he burned two mills at Egremont. In the district of Furness he set fire to various places and lifted spoil. The Scots burned the lands round Cartmel Priory taking away cattle and spoil, before moving on to Lancaster where the town was burned except the priory of the Black Monks and the house of the Preaching Friars. They stayed at Carlisle for five days trampling and destroying as much of the crops as they could by themselves or their beasts. How far does the source illustrate the strategies used by Robert Bruce to attain a peace settlement with England? (10) From A history of Scotland, Fiona Watson, 2001. The raids in England had at least provided the Scottish war chest with an unprecedented and reasonably regular income. Ireland proved that the Bruces were not invincible. The campaigns, some of which were led directly by King Robert, were both inglorious and miserable. The fact that the Scottish king was prepared to risk both his own life and that of his brother on this venture must also have forced the political community to realize that Scotland’s best interests might still come second to those of the Bruce dynasty. The death of Edward Bruce in October 1318 finally put an end to this military fiasco. How far does the source illustrate the problems met by Bruce in his attempts to attain a peace settlement with England? (10) 17 The barons’ letter to the pope (The Declaration of Arbroath) 1320 18 19 20 Robert Bruce’s response to the papal envoys who urged him to agree to a truce imposed by the pope, 1317. I am in possession of the kingdom of Scotland. All my people call me king, and foreign princes address me under that title, but it seems that my spiritual father, the pope, and my holy mother, the Church, are partial to their English son. Had you chosen to address such letters with such an address to any other sovereign prince, you might perhaps have been answered in a harsher style, but I respect you as messengers of the Holy See. How useful is the source in explaining why the Declaration of Arbroath was sent to pope John XXII in 1320? (5) From Independence and nationhood: Scotland 1306-1469, Alexander Grant, 1984. At the beginning of the 1320s Robert I was no nearer his goal of winning English recognition of Scottish independence. In addition there was a problem with the papacy. The popes were reluctant to recognize someone who had seized the throne from the legitimate king and killed one of his rivals in a church. Furthermore in 1317 Robert refused to agree to an Anglo-Scottish truce negotiated by papal envoys that would have prevented the Scots from recapturing Berwick. The papacy wanted peace throughout Europe, to mount a crusade against Islam. Because of English propaganda, Robert I appeared as one of the main obstacles. Accordingly in the winter of 1319-1320 a series of papal bulls was issued, which excommunicated Robert and his supporters, summoned him and four bishops to the papal court, released his subjects from their allegiance, and placed Scotland under an interdict1 prohibiting almost all religious activity. 1 A prohibition order 21 From The Declaration of the Clergy, 1309 Be it known that when that when a dispute had arisen between the lord John Balliol, lately raised to be king of Scotland by the king of England, and the late Robert Bruce of worthy memory, grandfather of the lord Robert, the king who now is, the faithful people always held without doubting, that the said lord Robert was the true heir after Alexander III. And the people of the kingdom, by the providence of the Highest King, unable to bear any longer so many and such great heavy losses, by Divine instigation, agreed on the said Robert, the king who now is, in whom the rights of his father and grandfather, in the judgment of the people still reside, and with their consent he was raised to be king. From The Declaration of Arbroath, 1320 From countless evils we have been set free, with the help of Him Who heals and restores, by our most tireless Prince, King and Lord, the Lord Robert. He, in order that his people might be delivered out of the hands of our enemies, met toil and fatigue, hunger and peril, and bore them cheerfully. Him, too, divine providence, his right of succession according to our laws and customs which we shall maintain to the death, and the due consent of us all, have made our Prince and King. To him we are bound both by law and by his merits that our freedom may be still maintained, and by him, come what may, we mean to stand. To what extent do the sources agree about why Robert Bruce became king of Scots? (5) 22 From Medieval Scotland: the making of an identity, Bruce Webster, 1997. The barons’ letter was part of the planned response to a threatening situation. It was, however, a literary composition of remarkable power, terse, effective in its rhetoric, and brilliantly clear in its message. This ‘Declaration of Arbroath’ as it became widely known in the seventeenth century, was to become a classic expression of Scottish national identity, much reprinted and quoted. It has come down to us in a contemporary version, a ‘duplicate original’ now in the Scottish record Office. This last, though it may have been seen by the barons in whose name it was issued and whose seals appear on it, seems to have attracted no special notice at the time. The only accounts to quote it are two fifteenth century chronicles. The text therefore was available, but there is little sign of earlier interest in it. From Scotland: the later Middle Ages, Ranald Nicholson, 1974. By any standards the Declaration of Arbroath is an impressive and eloquent document. It is the solemn protest of a small country against the aggression of a more powerful neighbour, an appeal on behalf of national freedom. It may therefore not seem right to question whether the ideas arose spontaneously in the mouths and hearts of the eight earls and thirty-one barons in whose name it was sent, or to question whether they ever met in Arbroath in 1320. Most probably they merely agreed to a royal request to bring or send their seals. That the letter was an essay in propaganda can hardly be doubted. Its Latin eloquence suggests it was penned by Bernard, the Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland. From The wars of the Bruces: Scotland, England and Ireland, 1306-1328, Colm Macnamee, 1997. In 1320 a shadowy conspiracy against Bruce came to light. The occasion for the conspiracy was the making of the Declaration of Arbroath, the famous letter from the earls and barons of Scotland to Pope John XXII. It was a masterpiece of nationalist rhetoric, and was intended to be interpreted by the pope as a spontaneous expression of outrage from the community of the realm of Scotland at English machinations against King Robert at Avignon. The letter was of course concocted in Bruce’s chancery at Arbroath. Seals were collected from individual barons named in the letter and appended to the document. The process of collecting seals and their use on a document justifying Bruce’s kingship seems to have angered several magnates and stirred up some latent Balliol sentiment. To what extent do the two sources agree about the Declaration of Arbroath? 23 (5) From Scotland: the story of a nation, (by Magnus Magnusson), Ted Cowan, 2000. Everyone knows the freedom clause, the ‘as long as but a hundred of us remain alive’ bit. But much more significant is the earlier sentence, about removing Bruce from the throne and replacing him if he fails to live up to expectations – because here we have the idea of ‘elective kingship’, of the contractual theory of monarchy: the king is answerable to his subjects exactly as the subjects are answerable to the king. This is the first time in European history that we have a clear articulation of this view. So the declaration of Arbroath is not only one of the earliest manifestations of nationalism – it is also one of the earliest manifestations of constitutionalism. 24 The Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton 1328 From The Bruce, John Barbour, 1370s, edited and translated by Archie Duncan. In 1327 King Robert gathered a great host, and divided his army into three parts. One part went to Norham unhindered, and there a close siege was set. The second part went to Alnwick and set a siege there. The king left his men before these castles and went on his way with the third part from park to park, for his recreation, hunting, as though it was his own property. To those who were with him there he gave the lands of Northumberland that lay nearest to Scotland in fee2. He rode like this destroying, until the king of England, on the advice of Mortimer and his mother, who at that time were his guides (for he was then young) sent messengers to King Robert to treat for peace. How useful is the source in explaining why Robert Bruce was able to secure a peace settlement with England? (5) From A history of Scotland, Fiona Watson, 2001. The Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton concluded in 1328 provided an acceptance of both Bruce’s kingship and Scotland’s independent status, as well as heralding a marriage between Bruce’s four-year old son, David, and the new English king’s sister, Joan, and the payment of £20,000 by the Scots. Perhaps the treaty can be criticised for failing to accommodate the long-standing grievances of those, both Scots and English, who had lost lands as a result of Bruce’s seizure of the throne in 1306. However, we must acknowledge that getting the treaty at all was a dream come true for both Bruce and Scotland. Besides, it is hard to see how these grievances could have been dealt with considering that these lands were now occupied by Bruce supporters who surely would have been as bitter about being turfed out at this stage. 2 Land granted in return for feudal service 25 From The Chronicle of the Scottish people, John of Fordun, 1370s. Ambassadors were sent by the king of England to the king of Scotland at Edinburgh, to arrange and treat for a firm and lasting peace, which should abide for all time. After much negotiation, the kings came to an understanding together about a lasting peace. And, that it might be a true peace, which should go on without end between them and between their respective successors, the king of Scotland, of his own free will, gave and granted 30,000 merks3 in cash to the king of England, for the losses he had brought upon the latter and his kingdom. And the said king of England gave his sister, Joan, to King Robert’s son and heir, David, for his wife, for the greater security of peace and the steady fostering of love. From The Bruce, John Barbour, 1370s, edited and translated by Archie Duncan. The king of England, on the advice of Mortimer and his mother, who at that time were his guides (for he was then young) sent messengers King Robert to treat for peace. They agreed as follows: to make a perpetual peace and with it a marriage between King Robert’s son, David, who then was scarcely five years old, and the lady Joan, who was sister to the young king who ruled over England and she was then seven years old. They gave up in that treaty various letters and claims which the English side had at that time against Scotland, and all the rights they might have to Scotland in any way. King Robert in compensation for many damages that he had done to the men of England in the war, was to pay full £20,000 of silver in good money. When they had agreed these points they arranged for the marriage to be at Berwick and fixed the day when it was to be. To what extent do the sources agree on the treaty signed between England and Scotland in 1328? (5) 3 The equivalent of around 67p 26 And finally ……… an issues question: From The wars of Scotland 1214-1371, Michael Brown, 2004. King Robert’s following was built around a close-knit group of adherents bound to his leadership. First among these was Robert’s last surviving brother, Edward, who led an attack on Galloway in June 1308 while Robert was in the north. In a similar fashion, James Douglas rose through a combination of service to Robert and personal ambition. During 1307, with some assistance, he had driven the English from Douglasdale, and by the end of the year he had secured the Forest of Selkirk. James Douglas was no freelance. He served in Edward Bruce’s army in Galloway and on the royal council, showing his loyalty to King Robert. Robert was able to leave the war in the south to such men. How fully does the source explain the reasons for the ultimate success of Bruce in maintaining Scotland’s independence? (10) 27