Authors` contributions

advertisement

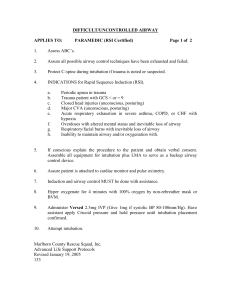

The role of an Anesthesiology curriculum at improving bagmask ventilation and intubation success rates of Emergency Medicine residents: A prospective descriptive study Hassan Soleimanpour1§, Changiz Gholipouri2*, Jafar Rahimi Panahi3*, Rouzbeh Rajaei Ghafouri4*, Robab Mehdizadeh Esfanjani 5*. § 1 . Corresponding author : Assistant professor of Anesthesiology, MD. Emergency Medicine Department, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Daneshgah Street, Tabriz-51664, I.R Iran. Tel: +989141164134 Fax:+984113352078 Email: h_mofid1357@yahoo.com or h.soleimanpour@gmail.com 2*. Associate professor of Surgery, MD. Emergency Medicine Department, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Email: c_gholipour@yahoo.com 3*. Associate professor of Anesthesiology, MD. Anesthesiology Department, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Email: jrjafar72@gmail.com 4*. Resident of Emergency medicine, MD (PGY3). Emergency Medicine Department ,Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Email: Rozbehrajaei@yahoo.com 5*. MSc St1, Department of Statistics, Tehran North Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. Email: mehdizadeh18@yahoo.com § Corresponding author *These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract Background: Rapid and safe airway management is paramount to the successful management of critically ill and injured patients in the emergency department. The purpose of our study was to determine success rates of bag-mask ventilation and tracheal intubations performed by emergency medicine residents, before and after an anesthesiology curriculum. Methods: A prospective descriptive study was conducted at Nikoukari Hospital, a teaching hospital in Tabriz, Iran. A total of 18 emergency medicine residents (Post Graduate Year 1) received traditional intubation and bag-mask ventilation instruction for 36 hours, as well as mannequin practice, in a skill lab. Then the same group trained in airway management in an operating room for 1 month, part of an Anesthesiology curriculum. Residents were asked to ventilate and intubate 18 patients (Mallampati class I and ASA class I and II) in the operating room, before and after this curriculum. The intubation was considered to be successful when it occurred on the first attempt within 20 seconds. Successful bag-mask ventilation was defined by an increase in ETCo2 to 20 mm Hg and back to baseline with 3 L/min fresh gas flow and the adjustable pressure limiting valve at 20 cm H2O. An attending Anesthesiologist confirmed the endotracheal intubation by direct laryngoscopy and capnography and was always present in the operating room during the induction of anesthesia. Success rates were recorded and compared by using McNemar test in SPSS 15. Results: Before educational intervention in operating room, the participants had an intubation success rate of 27.7% (CI 0.07- 0.49) and the successful bag-mask ventilation was 16.6% (CI 0-0.34). After educational intervention in operating room Residents had an intubation success rate of 83.3% (CI 0.66-1) and successful bagmask ventilation was 88.8% (CI 0.73-1). The difference in intubation success rates and successful bag-mask ventilation before and after intervention were statistically significant, (P= 0.002 and P=0.0004 respectively). Conclusions: Emergency medicine residents’ success rate in airway management improved significantly after completing an Anesthesiology rotation, Anesthesiology rotations should be an essential component for emergency medicine training programs and such collateral curriculums should focus on the acquisition of skills in airway management. Key words: Education, Curriculum, Anesthesiology, Emergency Medicine Background: Emergency Medicine is a complex and dynamic specialty that has many interfaces, both in practice and in skills with other specialty areas. Rapid and safe control of the airway is paramount to the successful management of critically ill and injured patients in the Emergency Department (ED). Effective airway management is the central part of emergency resuscitation and many see it as an undisputable core skill for emergency physicians (EPs).1 However, an early study on ED intubations reported an alarmingly high complication rate for endotracheal intubations.2 Trainees must be taught the assessment and airway management of a critically ill patient. This includes decision making and accepting responsibility.3 In recognition of this, the Emergency Medicine Faculty have identified that all EPs will need to acquire the necessary skills to manage a patient’s airway for the initial 30 minutes after admission. In some instances this will require the administration of drugs to facilitate tracheal intubation safely.3 Finally, it is important not to try to turn EPs into anesthetists, but instead equip them with the skills they need for their own environment and the problems they face.4 The current basic skills, listed in trainees’ logbooks are insufficient. All of this must mean closer cooperation between the two emergency medicine and anesthesiology specialties, starting at collegiate and extending down to departmental level.3 As concurrent failure of tracheal intubation and mask ventilation may ultimately result in death or brain damage, these two basic techniques are the most important that an anesthetist learns. Instead of learning the use of a simple face mask and tracheal tube, today’s trainee is faced with an ever increasing number of airway devices and techniques.5 Although there are numerous opportunities to learn outside the operating theatre, airway management trainees must be given the opportunity to practice maneuvers in a controlled setting. An Anesthesiology rotation is an important component of Emergency Medicine training that should focus on the acquisition of airway skills. Consideration should be given to the development of a set of specific objectives to assist planning training programs and monitoring progress.6 For the past 25 years, higher specialist trainees in Accident and Emergency Medicine in the United Kingdom (UK) have been required to complete a minimum three month secondment in anesthesia and intensive care. In the early days of training in Accident and Emergency Medicine, the goal was to orient trainees who were predominantly from medical and surgical backgrounds to the concepts of anesthesia and specifically to train them in basic and advanced airway management skills.7 The most important places for anesthetic training are the ward, the operating theatre and the intensive care unit, not the classroom and the library. The influence of clinical teachers as role models for students cannot be underestimated.8 Good anesthesia teachers combine enthusiasm, willingness to teach and an "inquiry" approach.9 Graham has described the training requirements for higher specialist trainees in Emergency Medicine (box 1).7 Although trainees have an opportunity for the development of specific learning objectives for airway management during this period in the skill lab and operating room, our research is based on two most important skills in airway management. The aim of this study was to determine success rates of bag-mask ventilation and tracheal intubation performed by Emergency Medicine residents, before and after an Anesthesiology curriculum. Methods: A prospective descriptive study was conducted at Nikoukari Hospital, a teaching hospital in Tabriz, Iran. Our emergency medicine residents were trained in a skills lab on dummies and were then asked to bag mask ventilate and intubate patients in operating room before and after an anesthesiology training program. They asked to perform the procedure as part of their normal training program. There is a mandatory 1-month rotation in Anesthesia during the first year of the Emergency Medicine residency (EMR-1). During this month, the EMR-1s learn airway management and perform intubations on stable patients in the operating room. Anesthesiology curriculum had been approved in our university for emergency residents during their residency program and they must attend in this rotation. Furthermore all the ED residents who take part curriculum are eligible for bag-mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation, since they already passed necessary training in skill lab and got certificate. In this study, a total of 18 EMR-1s received traditional instruction about orotracheal intubation and bag-mask ventilation in the Skill Laboratory (Skill Lab), using mannequin-based simulators, for a 36-hour period. The training program in skill lab includes a period of theoretical instruction that EMR-1s received training in orotracheal intubation and bag-mask ventilation, using Power Point software and video-based training. The residents were then asked to bag-mask ventilate and intubate the mannequins for at least 20 times, as hand-on training. The movements required to successfully perform these procedures were instructed by an attending anesthesiologist, as well as theoretical instruction. The theoretical and hand-on training portions in this 30-hours course were approximately equal. All of participants passed a certification exam. Then the same group trained in airway management in operating room for a 1-month period, as part of an anesthesiology rotation. During this period, EMR-1s received an extensive didactic review of airway management, simple airway maneuvers, bagvalve–mask ventilation and oral intubation. The rotation also include the basic skills of airway assessment, mask ventilation, tracheal intubation and airway decision making. They were asked to bag-mask ventilate and intubate 36 adult patients (18-52 years old) in operating room, before and after this 1-month anesthesiology rotation. Every resident performed both procedures on 2 patients. The selected patients had Mallampati class I and ASA class I and II. The exclusion criteria were: presence of beard, lack of teeth, facial anomalies, having a nasogastric tube, morbid obesity and a history of snoring. These patients presented to operating room for elective ophthalmic surgery. Our patients were aware that they are present in a teaching hospital where the study was performing and they asked for consent before admitting. On the other hand, because of our study has been designed for description efficacy of anesthesiology curriculum and we did not do any intervention on the routine training program; ethical approval was not required for our study. For all intubations, patients were connected to a cardiac monitor, an automated blood pressure monitor, pulse-oximeter and capnography. An attending anesthesiologist supervised the process all of the time. All patients were hydrated preoperatively with Ringer's Lactate solution 10 mL.kg-1. After pre-oxygenation for three minutes and premedication with midazolam 0.02 mg.kg-1 and fentanyl 1.0 µg.kg-1, anesthesia was induced with propofol (2 mg.kg-1) and atracurium (0.5 mg/kg). Once the patients became unconscious, as judged by loss of response to command and loss of eyelash reflex, mask ventilation was initiated. The total fresh gas flow (FGF) on the anesthetic machine was set at 3L/min and the adjustable pressure limiting (APL) valve at 20 cm H2o. A standard circle circuit and 2 L bag were used. Achieving adequate tidal volume with bag-mask ventilation requires a tight mask seal and appropriate compression of the bag.10 The end point for successful bag–mask ventilation was defined as an ETco2 trace increasing to 20 mm Hg and back to baseline. If this was achieved at total fresh gas flow of 3 L/min and APL valve at 20 cm H2o, bag–mask ventilation was considered to be successful as the primary outcome. If it was not achieved, a protocol was followed to ensure adequate bag–mask ventilation. This protocol that was defined as a secondary outcome included increasing the FGF to 6 L/min, closure the APL valve to 30 cm H2o, use of the oxygen flush device and use of a two-person technique (resident uses 2 hands to secure the mask while an assistant squeezes the bag).11 After 3 minutes the trachea was intubated with an appropriate endotracheal tube. An intubation attempt was defined as placement of the laryngoscope into the patient’s mouth, even if no attempt was made to pass an endotracheal tube.12 The intubation was considered to be successful when was completed on the first attempt and within 20 seconds. This time starts when the blade was placed in the mouth and end of procedure was considered when the balloon was inflated. When the time exceeded 20 seconds, the procedure was aborted and intubation was performed by the supervising anesthesiologist. The same attending anesthesiologist was always present in the operating room during the procedures. He has direct responsibility for all intubations performed in the operating room and has the discretion to determine which resident performs the ventilation and intubation and how the method was used. To confirm tracheal intubation, direct laryngoscopy by the attending anesthesiologist and a capnography (end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor) were used in all instances, along with inspection and auscultation of the chest and epigastrium immediately after intubation. He also recorded the time and success rate of intubation and successful bag-mask ventilation. Success rates in both bag-mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation were recorded and compared before and after anesthesiology rotation. The results were analyzed using SPSS 15 and compared by using McNemar and marginal homogeneity test. Results: There were 18 EMR-1s who performed both bag-mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation on 36 patients at the start and end of the anesthesiology rotation. All of patients were male with mean age of 37. Before the anesthesiology rotation the participants had successful bag-mask ventilation rate of 6 of 36 (95% confidence interval= 0% – 34%) and intubation success rate of 10 of 36 (95% confidence interval = 7% – 49%). After the rotation, successful bag-mask ventilation had been reported in 32 of 36 cases (95% confidence interval= 73% –100%) and successful intubation in 30 of 36 (95% confidence interval= 66% – 100%) cases (Figures 1&2). The difference in successful bag-mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation before and after the rotation were statistically significant, P=0.0004 and P=0.002 respectively. Thirty of 36 residents, who were unsuccessful in bag-mask ventilation, had to ensure adequate ventilation by using ancillary techniques. The failure numbers decreased to only 4 after intervention (Tables 1&2). The use of ancillary techniques to produce adequate bag-mask ventilation was reduced after the Anesthesiology rotation and there was a statistically significant difference before and after the rotation (P= 0.001). The average time spent for successful endotracheal intubation was 18.6 ± 1.67 seconds before the Anesthesiology rotation. This value decreased to 13.6 ± 1.34 seconds at the end of the rotation in the same group (P= 0.043). Discussion: With the development of emergency medicine as a recognized medical specialty, emergency airway management has become an essential skill for emergency physicians. There has been remarkably little literature describing the airway management skills of emergency physicians. We undertook this study to determine the role of a 1-month anesthesiology rotation at improving EMR-1s airway management skills. The only set of specific objectives for an anesthesiology rotation by an emergency medicine trainee has been published with reference to training in the United States of America.13 Assessment of the airway constitutes one of the most important aspects of airway management. It is unclear what constitutes an acceptable minimum training in airway assessment. Reports of management of the difficult airway consistently refer to the difficulties of its predicting it despite using multiple accepted methods of assessment. It is obviously important to recognize signs of a potentially difficult intubation early in resuscitation, but the emergency physician must remain aware that unexpected difficulties with intubation will occasionally occur.7 Amarasinghe et al have identified the core components of an Anesthesiology curriculum for emergency medicine trainees. They collected and ranked the skills judged to be most useful on an Anesthesiology rotation. The results demonstrated that the most important skills to be learned on an Anesthesiology rotation are orotracheal intubation, bag–mask ventilation, jaw thrust/chin lift maneuver and use of oral and nasal airways.6 According to the results of Amarasinghe’s study, our research focused on assessment of the two most important and highly useful airway management skills, bag-mask ventilation and orotracheal intubation. Our study showed that residents, who received traditional instruction about airway management in the skills lab, using mannequin-based simulators, could not manage the patient airway ideally. They had difficulties ventilating and intubating patients with relatively easy airways in the operating room setting, although all of participants passed a certification exam. Because of significant acquisition of airway management skills after human-based instruction, we believe it is necessary to use this method in addition to traditional mannequin-based training. It has recently been suggested that future training of United Kingdom emergency medicine specialists should include a one year anesthesia and critical care rotation, involving six months of full time anesthesia followed by six months of full time critical care.14 Another study showed that the Anesthesiology rotation is an essential part of Emergency Medicine training and that the optimal duration is approximately 6 months, preferably in the first two years of advanced training.6 It seems that, despite the rotation’s efficacy on acquisition of airway management skills, its length in our department may not be enough and should be extended. It will also be important in the future to carefully study the effects of increased length and quality of training for emergency physicians on the success and failure rates for airway management in the Emergency Department (ED) as performed by residents. It must also be remembered that the acquisition of anesthesiology-related knowledge and skills is not confined to an anesthesiology rotation. In fact, many of these may be learned better in other settings. For example, the pharmacology knowledge related to this area is an important part of the primary examination curriculum. Intubation of trauma and unstable patients may be best learned in the Emergency Department (ED) under appropriate supervision, because these patients are different from those encountered in elective anesthetic practice.6 It is widely accepted that endotracheal intubation in the emergency room is significantly more hazardous and associated with an increased rate of difficult intubation and failed intubation than that in the operating room.15 A difficult airway is not uncommon in the emergency setting. There is no specific training program in the curriculum for trainees to develop difficult airway management skills. Maintenance of skills in emergency airway management is also a subject of considerable debate presently. There is no objective scientific data to support a minimum requirement of numbers of emergency or rapid sequence intubations (RSI) to be performed by emergency physicians (or indeed Anesthetists) to maintain competency in this area. The figures from the Trauma Audit Research Network suggest a maximum of approximately 6 RSIs per month, per department (based on an average of 68,000 patients per year), which, if staffed by four consultants in emergency medicine, will equate to 1–2 RSIs per consultant per month. The Scottish Trauma Audit Group data also suggest that the individual consultant in emergency medicine would be likely to be involved in two to three RSIs per month.7 Due to the presence of a large number of patients to our ED (near 6000 patients each month); the individual skills maintenance will not be difficult for the practicing residents in emergency medicine. This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Our sample size was small and suboptimal. Further prospective studies are needed to be done in larger sizes to validate the role of such rotations. Another limitation of this study is that complications were not assessed. There is certainly the potential for selection bias that could be responsible for the differences noted in these rates. Also, study was held on patients with relatively easy airways, raising the possibility that the results are not generalizable. Other limitations: Single site Small number of participants at a single site Results are not completely unpredictable given the instruction was 30 hours vs. 1 month Do not know who many raters there were, or whether there was strong interpreter reliability No control group We did not determine adequate numbers of attempts to achieve reasonably consistent skills in bag-mask ventilation or endotracheal intubation. In the US, several studies have reported on the requirements and experience of their residents in Emergency Medicine. Although it is difficult to be clear on exact numbers and accepting that there will always be variations between people, it would seem that novice anesthesiology residents require 80 or more intubations to achieve reasonably consistent skills in endotracheal intubation.7 Hayden and Panacek reported that the mean number of intubations per trainee was 75 (95% confidence intervals 62 to 87); this is over a three year residency in emergency medicine in a US setting.16 More studies should be carried out to determine the number of endotracheal intubations required to achieve an acceptable level of procedural competency. Conclusions: Since, Emergency Medicine residents’ success rate in airway management improved after rotating on an anesthesiology rotation; anesthesiology rotations should be a mandatory component of Emergency Medicine training programs. We believe that a standardized theoretical instruction program in combination with a practical anesthesiology rotation improves the skills of airway management in Emergency Medicine residents. Airway management training is a continuous process that should begin with theoretical instruction, continue in the skills lab and operating theatre and end in the ED. All of the above mentioned steps should be supervised by attending of Anesthesiology and/or Emergency Medicine. Competing interests The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests. Authors' contributions The authors were involved in patient management or writing of the manuscript. Acknowledgements We thank Dr.Terry Kowalenko, MD, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine ,University of Michigan. Actually, We don’t know how we could express our deep gratitude because of her comment on our paper. They were very instructive and helpful for us. We will be deeply and always proud to remind having her guidance in scientific issues as well as in research ethics. References: 1. Walls RM. Rapid-sequence intubation comes of age. Ann Emerg Med 1996; 28:79– 81. 2. Taryle DA, Chandler JE, Good JT, et al. Emergency room intubations- complications and survival. Chest, 1979; 75: 541-543. 3. Gwinnutt CL. The interface between anaesthesia and emergency medicine. Emerg. Med. J 2001; 18:325-329. 4. Carley S, Gwinnutt CL, Butler J, Sammy I, Driscoll P. Rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department: a strategy for failure. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:109–113. 5. Mason RA. Education and training in airway management. British J of Anaesthesia, 1998; 81:305-307. 6. Amarasinghe V, Kelly AM, Rogers I, Jacobs I. Identifying the core components of an anesthesiology curriculum for emergency medicine trainees in Australasia. Emerg Med J 2000; 12:344-348. 7. Graham CA. Advanced airway management in the emergency department: what are the training and skills maintenance needs for UK emergency physicians? Emerg. Med. J, 2004;21;14-19 8. Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1997; 78:633-634. 9. Cleave-Hogg D, Benedict C. Characteristics of good anesthesia teachers. Canadian journal of Anesthesia, 1997; 44:587-591. 10.Wenzel V, Idris AH, Montgomery WH, et al: Rescue breathing and bagmask ventilation. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 37:36. 11. Conlon NP, Sullivan RP, Herbison PG, Zacharias M, Buggy DJ. The effect of leaving dentures in place on bag-mask ventilation at induction of general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:370-373. 12. Sakles J, Laurin E, Rantapaa A, Panacek E. Airway management in the Emergency Department: A one-year study of 610 tracheal intubations. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 1998; 31:325-332. 13. Guttman TG, Hamilton GC. Objectives to direct the training of emergency medicine off-service rotations: Anesthesiology. J. Emerg. Med. 1992; 10: 357–66. 14. Gwinnutt CL. The interface between anaesthesia and emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2001; 18:325–6. 15. Walls RM, Vissers RJ, Sagarin MJ. Emergency department intubations-final report of the National Emergency Airway Registry Pilot Project. [Abstract]. J Accid Emerg Med 1998; 15:392. 16. Hayden SR, Panacek EA. Procedural competency in emergency medicine: the current range of resident experience. Acad Emerg Med 1999; 6:728–35.