Michelle Berditschevsky and Peggy Risch

advertisement

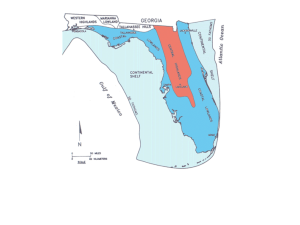

Feature Claiming the Highlands Geothermal Mining Confronts an Ancient Native Tradition by Michelle Berditschevsky and Peggy Risch Terrain Magazine, Summer 2000 Rising out of a sea of blue-green forested hills northeast of Mount Shasta, the Medicine Lake Highlands volcano encompasses California's most diverse volcanic fields, on the continent's largest shield volcano. The volcano's caldera, a 500-foot-deep oval crater about six miles long and four miles wide, was formed when underground magma flows collapsed the dome's summit in Pleistocene times. Later eruptions built a ring of smaller volcanoes around the rim of the basin. The azure waters of Medicine Lake lie embedded in this million-year sculpture of volcanic fury, with its striking variety of textures — lava flows, clear lakes, mountains of glass-like obsidian, slopes of white pumice, dark boulders, and silver-green mountain hemlock. The Highlands' clear skies are home to eagles, goshawks, and rare bats. Tall forests shelter martens, fishers, and unknown numbers of sensitive plants. Filtered through porous rock, the Highlands' aquifer forms a major source of spring waters flowing into the Sacramento River. For ten thousand years by the archaeologist's count, as far back as memory and signs hewn in stone can reach, the Medicine Lake Highlands have been a place of traditional spiritual practice. To Native American tribes known as the Ahjumawi (Pit River), Modoc and Shasta—as well as to more distant tribes — the landscape is a living scripture in which higher beings have left messages for the first people of the land. Today, the people continue their prayer, vision questing, healing, and subsistence practices in the Highlands. In this remote area there are no freeways, no trains, no factories, no power lines, no bright lights. Narrow winding roads take you to Glass Mountain, Pumice Craters Lava Flow, Yellow Jacket Ice Cave, Red Shale Mountain, Burnt Lava Flow, Painted Pot Crater, Medicine Mountain. Absent is the grinding roar of engines we are accustomed to. The contemporary industrial obsession with resource extraction has not gotten a foothold here — and will not if Native American and environmental defenders have their way. Expected as early as May, final decisions are now imminent on two geothermal industrial "parks" in the Medicine Lake Highlands, with a potential for several more. Each of the complexes could cover up to eight square miles with power plants, well fields, toxic sump ponds, roads, above-ground steam pipes, and transmission lines fragmenting the landscape — all within half a mile southeast and two and a half miles northwest of Medicine Lake. Steam plumes, night lighting, chemical odors, and the noise of well drilling, construction, and operations would intrude upon the air, the water, the star-paved night sky, the serenity of the landscape, and the practice of ancient traditions. Linked by traditional running paths, Mount Shasta and the Medicine Lake Highlands share tribal stories that weave eternity, time, and the land together. "The Lake, the Mountains around it, the springs, hunting grounds, and gathering areas are an interconnected whole whose parts are tied together through the Creator's power or spirit that inhabits them," said Floyd Buckskin, Headman of the Ahjumawi Band, Cultural Spokesperson for the Pit River Tribe, and Chairman of the Native Coalition for Medicine Lake Highlands Defense. "When someone acts out and contemplates the things the Creator has done in times of creation, these are the models and examples for humans to follow." In the Pit River Tribe's creation story, the Creator created the world from Mount Shasta, went to Medicine Lake and, in the geographic features of the lake and the Highlands, left important instructions on how to live. "At the Creation of the World the Creator made laws for nature and man to live by," Buckskin says. "Sometimes the laws were established by the Creator's actions. When the Creator and His Son swam in Medicine Lake, this set the pattern for the people to follow. In many places They would do some act, speak some word, which sets the Holy Pattern, the Sacred Laws." Within the Medicine Lake Highlands, "traditional doctors, warriors, and those seeking healing would journey to various sites to seek their power, whether it was personal power or doctoring power," says Buckskin. "Among the Shasta People, young men would have to spend a number of days in the Highlands before they could be called warriors." Glass Mountain, on the northeast rim of the caldera, is a prime source of high-quality obsidian, valued for projectile points and ceremonial uses by tribes as distant as the coastal Yurok. Wild currant, gooseberry, and other local plants are used as food; woodwardia is gathered for basketry. Prince's pine and mountain hemlock are used for healing, as is the pure water from lakes and springs. Their association with specific sites give medicinal plants spiritual properties that contribute not only to physical but also to spiritual healing. "(The Highlands are) one of the most sacred areas in Pit River country," says Theodore Martinez, spiritual healer from the Atsuge Band of the Pit River Tribe who uses the area for healing rituals, plant gathering, and ceremonies. "It is just as holy and sacred as the Black Hills in South Dakota." People come from great distances to the sacred waters of Medicine Lake and surrounding lands, says Ed Sanderson, traditional practitioner from the Karuk Tribe, who uses the Highlands. "Tribes from Idaho and Montana use it," he says, "The area is a medicine-man training ground for the whole of Turtle Island (North America)." In more recent history, the area provided refuge from brutal encounters with settlers and the US Army. "All the prophecies talk about going to the high places as places of refuge," says Buckskin. "The Medicine Lake Highlands are where we went in the 1850s when Lieutenant George Crook rounded up the Pit River Indians to forcibly remove them from their lands. The Modoc people were trying to get to the Highlands during the Modoc Wars, and that's why the army was trying to prevent them. Because the army knew that once the Modocs escaped to the Highlands, then there would be no way to capture them." The Highlands are "more than archaeological sites and human remains," Martinez explains. "These grounds are still utilized today. If there weren't anything there, you wouldn't feel anything when you go there, and you would go back with the same sickness you came to heal." The energy under the ground "is tied to every one of these mountains around there, tied to Medicine Lake, the springs, the meadows, the plants, the animals. There are things we're talking about that aren't acknowledged as part of our culture. That energy that they want to take, that's a part of the spiritual power living there. The whole caldera is an energy center, that's why they call it Medicine Lake Highlands." Between 1982 and 1988, the US Bureau of Land Management auctioned off a series of leases for geothermal energy exploration on 55,000 acres in the Medicine Lake Highlands. With "limited" public disclosure and no input from the tribes, the BLM sold the leases to three giant oil companies for $10.6 million, says BLM Geothermal Project Lead Sean Haggerty. But as attorneys for the Native Coalition argued in an April 1999 challenge, the leases promised more than they should have. They were issued based on a 1981 declaration, done jointly with the Forest Service, that exploration would cause "no significant impact." But the leases actually granted exclusive rights not just to explore, but to "remove (and) sell" geothermal resources, according to Randall Sharp, geothermal project coordinator for the Forest Service and BLM. Based on the promise of development rights, two energy companies have invested millions of dollars in purchasing leases and on environmental studies. In issuing the leases without full environmental impact statements, the agencies left themselves open to litigation; if the final analysis finds that full development would cause adverse impacts, the projects could fall through. Even though the agencies later acknowledged traditional Native uses of the land, they admit they issued leases with little effort to study the extent of cultural values or how the development would affect them. "We didn't get input face to face," says Haggerty. By 1998, all but one of the leases had expired. By then, draft environmental impact statements (EISs) had determined that development would have significant adverse impacts. But in May 1998, without providing public notice or review, the BLM granted retroactive 40-year extensions to the leaseholders, Haggerty says. In December 1999, environmental groups appealed renewal of the leases; a decision is pending. By 1995, two multinational energy corporations, San Jose-based Calpine and Omaha-based CalEnergy, had acquired the leases in the Highlands. By 1997, each company submitted development plans — Calpine at Fourmile Hill; CalEnergy at Telephone Flat. The Bonneville Power Administration, a federal agency which had contracted to buy power from the companies, has promised them $20 million if the projects go on line. Proposals for the two power plants, each costing roughly $100 million to build — with associated wellfields, pipelines, and transmission lines — were evaluated in EISs released in 1997 and 1998. Within weeks of release of the environmental documents, homeowners, the Native Coalition, and environmental groups mobilized, combing through the documents, attending public meetings, educating the public, and bringing concerns to the agencies. Native Americans and activists protested at the US Forest Service office in Alturas, Martinez performed a traditional prayer ceremony, and posters went up opposing "desecration of our sacred lands." The group has submitted extensive written comments on the plan. The Pit River Tribe and the Native Coalition have developed an informal NativeBioregional Alliance with the Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center. In the past year, the tribes have sent two delegations to Washington, DC, to educate decision makers on the sacred meaning of this extraordinary landscape. A final decision on the EISs is expected as early as May, Haggerty says. The geothermal projects are driven by "green energy" subsidies. In spring 1999, the governor-appointed California Energy Commission pledged $49 million over five years to the two companies — assuming the projects begin operation by January 1, 2002. Funded by consumer electric bills under deregulation, the two awards ($21 million and $28 million respectively) account for nearly one-third of the subsidies allotted to 55 green energy projects, says commission spokesperson Tim Tutt. On a national scale, the Department of Energy has launched a Geowest Initiative calling for geothermal mining to meet 10 percent of the West's electrical needs by the year 2020. As critics point out, that is support diverted from conservation efforts — and cleaner energy alternatives such as solar. Unlike fossil fuels, geothermal energy does not produce large quantities of "criteria pollutants," particularly carbon dioxide, sulfur oxides, and nitrogen oxides. However, geothermal development has its own impacts. Developers tap large underground beds of boiling brine sitting on top of magma-heated rock. To mine the brine at the Highlands, they would have to drill more than 80 wells during the 45-year life span of the two 49-megawatt plants. Drilling production wells, an arduous 25- to 90day process, requires boring down 9,000 to 10,000 feet. Miles of above-ground, high-pressure pipelines would carry the 400-degree Fahrenheit water to a power plant. These nine- to ten-story power plants would be the tallest buildings in rural Siskiyou County, in the midst of the Modoc and Klamath national forests. The hot, viscous geothermal brine contains mercury, arsenic, boron, cadmium, and other hazardous compounds. The plants would release the fluid as steam to turn constantly humming turbines. High voltage transmission lines would buzz roughly 24 miles through the Medicine Lake Highlands to the nearest power station. According to the environmental documents, bald eagles could die colliding with transmission lines, and the development would disrupt habitat for endangered and sensitive species including bats, goshawks, and pine martens. But the coalition also points out that steam plumes release large quantities of moisture containing traces of brine contaminants. In the bowl-shaped caldera, most of the contaminants wouldn't leave the local ecosystem. According to the plan's documents, about 18 percent of the geothermal fluids dissipates into the environment, and the remaining 82 percent is re-injected into the earth. Sump ponds with a capacity of 500,000 to 1 million gallons would hold the spent geothermal fluids before more miles of pipelines take the material back to the periphery of the plant site, to be pumped back into the ground. Without this process, the land would subside from the fluid loss. The re-injection can produce small earthquakes, contaminate drinking water sources, and with time, cool the geothermal resource so that it can no longer make steam. After pressure loss and cooling, wells would be abandoned, sealed, and could rupture or leak years after a plant has been decommissioned. "Although geothermal energy is sometimes referred to as a renewable energy resource," says a 1994 US Geological Survey report, "this term is somewhat misleading." Scientists are studying whether the replenishment of a hydrothermal system would require "hundreds or thousands of years," the report says. "We clearly support green energy if it's truly green. This is not," said Clancy Tenley, Indian program manager at EPA's San Francisco office, referring to the Medicine Lake projects. "It's unfortunate that subsidies would go to a project like this." In advocating any number of "green energy" projects, particularly geothermal, people are unwittingly advocating intrusions into some of the wildest places in the world. The volcanic "ring of fire," places where geothermal developments could be possible worldwide, can coincide with the purest water sources, often in uncharted and undocumented sacred areas. All told, the two Medicine Lake proposals could bring serious problems and uncertainties to the area. • Explosions: Although the documents fail to describe the hazards, they show 21 percent of geothermal facilities nationwide have had ruptures or "blowouts." A May 1998 blowout at the CalEnergy plant near the Salton Sea in the Imperial Valley devastated the area, particularly soils and vegetation. • Drilling blind: According to testimony by a hydrology expert, developers would have to drill through an 800- to 1,000-foot Highlands aquifer, risking water contamination — especially since the aquifer has not been adequately mapped. • Water pollution: A Bonneville Power Administration evaluation of various power sources puts it unambiguously: "Brine coming to the surface from supply wells and returning through injection wells has the potential to contaminate local water tables." • Water table: The Fourmile Hill exploration project alone would draw 200,000 gallons a day from wells at Arnica Sink within the Medicine Lake Caldera. • Acreage and fragmentation: Accounting for direct visual impacts, noise, odor, and lighting, direct effects would cover more than 24,582 acres — over 38 square miles. • Cumulative effects: As many as six power plants the size of the 49megawatt facilities currently proposed could be accommodated by the proposed 300-megawatt transmission corridor. • Seismic hazards: Environmental documents erroneously state that the nearest major earthquake faults are 50 to 75 miles away; the California Department of Conservation Division of Mines has located active faults with potential for 7.0 quakes within 12 miles of the proposed developments. Inadequately weighed against irreversible environmental damages and the loss of Native American culture, the plans project 19 permanent jobs, an annual revenue of $1.3 million to Siskiyou County, and federal royalties payments of $15 to $25 million over the first 20 years of the project. Of the 98 megawatts the two companies propose to extract from the Highlands, only 80 megawatts would be left over from running the two plants. That energy — along with the estimated 400 megawatts the projects do not immediately propose to extract — could be better obtained by intelligent energy conservation, the coalition argues. The plants might not even work. "Our power project development and acquisition activities may not be successful," Calpine admits in a recent report. "The development of power generation facilities is subject to substantial risks including start-up problems, the breakdown or failure of equipment or processes, and performance below expected levels of output or efficiency." In the face of the evidence, and in the face of two multinationals with legal resources, the agencies find themselves between a rock and a hard place: "Construction of the projects would significantly impact an area holding spiritual and cultural significance for regional Native Americans," states a Forest Service briefing document. "There is a concern that denial of the projects would be a taking of property rights associated with the geothermal leases." In a July 1999 decision that strengthened the case for protection, the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places designated the entire Medicine Lake Caldera — "an interrelated series of locations and natural features" — eligible as a Traditional Cultural District. The Keeper, Carol Shull, cited "historic and continuing value of the area to Native Americans for maintaining their traditional cultural identity." The Forest Service, which is responsible for the surface land (the BLM regulates underground resources), has yet to evaluate important areas outside the caldera, including sites in the Fourmile Hill area. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the California State Historic Preservation Officer have taken strong positions to assure that decision-makers adequately consider traditional cultural values. But even with the National Register's acknowledgment of sacred values, developers and land managers continue to reduce the land to an object of grids, profit charts, and product outputs, juggling quantities so that it seems possible to mitigate impacts. Agency analyses describe geothermal steam plumes, which would be visible from practically anywhere in the Highlands, as visible only if you look in that direction. Consider the tribal perspective: "When you're supposed to be in a state of deprivation of food and sleep, of contact with people and all worldly things, then any contact with humans, seeing the plumes, construction activities and operating activities, all will interfere with that pure state," said Martinez, the Atsuge Pit River healer. "A big part of utilizing these cultural resources is having no contact with other human beings or anything modern. The plumes, smells, lights (even downward-facing lights), structures, noise, etc. cannot be reduced to a level where they will not interfere with the heightened state of awareness that comes out of this state of deprivation." By way of mitigation, the agencies suggest that tribes could plan their cultural activities around schedules for roads construction, well drilling, or power plant construction to avoid the noise, increased traffic, air pollution, and other impacts. "We speak to our elders, and when it's time to go to a place, it's time to go, especially when elders send you at a moment's notice when there's something that has to be done," said Martinez. In ritual plant gathering "a healing ceremony may require a plant from a distinct area," says Buckskin, the Pit River Tribe spokesperson. "We need to protect the wholeness, so that plants from all specific locations are available and access is unobstructed." The plants must be protected: "The steam plumes might dissipate, but the chemicals would come back down through the clouds and the rain; those chemicals would enter the plants. The uncontaminated environment of the Highlands and the associations of that environment make all the plants special." The Medicine Lake Highlands contain sacred water, the essence of healing, which must be preserved, Martinez says. "Whatever happens to the Medicine Lake Highlands area affects our spiritual and physical existence, and our environmental existence because of the water, the largest source of fresh water coming into the Pit River." As Buckskin put it: "When the water is being used for spiritual and healing properties, we don't want anything else in there from geothermal development. Any impacts would fail to meet the Tribal water quality standards of purity for spiritual and medicinal use." In the end, there is a larger issue at stake at the Medicine Lake Highlands. To feel the spiritual quality of a place lets you know what behavior and activities the place can accept. In Native tradition, an empathetic sense of kinship can lead to a very exact reading of what the landscape needs — embracing long-range practices based on continuing observation and interaction. This reciprocal relationship to the land is as much an endangered species as the coho salmon, and its habitat is these sacred lands. A protected Medicine Lake Highlands, where that world view can still be predominant, allows the soul to connect to the land, to other life forms, and to healing with all our relations. In the words of Jerald Jackson, Spiritual Leader of the Modoc Tribe: "The Spirit of Creation, just being there with what I call my relatives — sun, wind, trees, rocks, brush, everything that God has created, I'm part of that when I'm out there at that altar, and it continues when I come away from that altar. That water out there, Medicine Lake, is sacred because it's the life blood of Mother Earth, it's also the life blood of the people." To Native Americans, cultural restoration — ensuring that places and traditional ways vital to cultural survival are preserved — means taking care of the land, listening to the land, the plants, the animals, and the wind; and avoiding damaging practices. As Willard Rhoades, Spiritual Elder of the Pit River Tribe, has put it: "Working on protection of these places lets you be adopted into the land. This is what allows you to understand." Michelle Berditschevsky is Project Director of the Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center and Secretary for the Native Coalition for Medicine Lake Highlands Defense. Peggy Risch is Environmental Research Associate with the Mount Shasta Bioregional Ecology Center. For more information, contact the coalition: P.O. Box 1143, Mount Shasta, CA 96067, or phone (530) 926-3397.