activist1 - University of Delaware

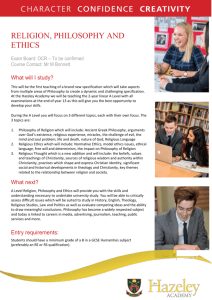

advertisement