AEA-E 2000 keynote

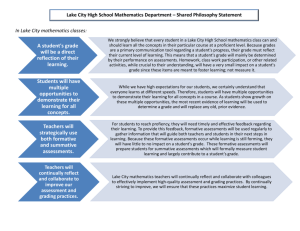

advertisement