dynamics of biting activity of c. imicola kieffer during the year

advertisement

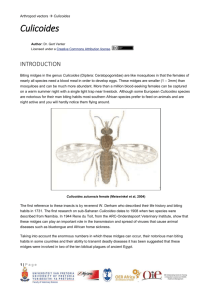

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE DYNAMICS OF BITING ACTIVITY OF C. IMICOLA KIEFFER (DIPTERA:CERATOPOGONIDAE) DURING THE YEAR Y. Braverman1, S. Rechtman2, A. Frish1, and R. Braverman3 Vol. 58 (23) 2003 1. Kimron Veterinary Institute, P.O.B. 12, 50250 Bet Dagan, Israel 2. Tichon Reali Highschool, Rishon Le'Zion, Israel 3. Industrial Management Engineering, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva Summary Collections from a bait calf yielded 520 C. imicola Kieffer. The calf’s back, in particular the black haired patches, were highly preferred as landing and biting sites. In only one out of six collection sites C. imicola were found in large numbers. The crucial importance of vision in detecting the host by c. imicola and other species was proved by using a variety of bait traps in Israel and Zimbabwe he landing and biting activity of C. imicola were limited to twilight times, with the largest peak occuring at sunrise. A constant ratio between parous and nulliparous C. imicola females was found at sunset, while a different ratio was found at sunrise. C. imicola constituted 98.5% of the Culicoides spp. collected at Bet Dagan. The constant ratio between nulliparous and parous females C. imicola, of 2:1 was obtained throughout the night hours. Numbers of C. imicola peaked during the autumn. The flight activity of C. imicola in July-August peaked between 3:00 am and 5:00 am. The peak hours varied from month to month corresponding to changes in day length, temperature, and relative humidity. Of all the meteorological parameters tested for their effect on population density, the only correlation was found with temperature showing numbers of C. imicola increasing between 17 and 25oC. Introduction The major species of Culicoides populations in the Middle-East have generally two seasonal peaks: a small one in the spring and a larger one in autumn (1). However in nightly suction light trappings throughout the year at Bet Dagan in 1982, only the autumn peak was detected (2). The hourly peak flight activity of C. imicola was found by Nevill (3) in South Africa to band between 1.00 am and 3.00 am. No distinction was made in this study between the nulliparous and parous components of the population. It was later found that females of different physiological ages differ in their diurnal activity (4). Suction light traps can provide only general information on the species composition within the attraction range of the traps, but not on the activity of the biting population, its hourly activity and physiological age. To obtain this information, studies using live hosts (5) were carried out in various places in the world to identify which Culicoides spp. bit different parts of the cow’s body. Culicoides brevitarsis Kieffer, which is a close relative to C. imicola, prefers to bite the back of cattle (6). It was therefore assumed that C. imicola has a similar preference. That C. imicola prefers to bite cattle has been known for many years (7), but its biting preference for various parts of the body has not been reported. The reported biting activity times of medically important Culicoides spp. is at dusk and dawn. Culicoides kingi Austen, a cattle feeder in southern Sudan, was found to have a biting peak before sunset, twice as much as the peak before sunrise (8). It was found in Alabama that Culicoides spp. prefer open fields for biting. The numbers of biting midges collected from a sentinel calf in an open field were 2.5 fold higher than those collected from a calf situated in a forest (9) and this might be because a host is more visible in the open (10). Preferred meteorological conditions for biting include: calm air or slight wind, high relative humidity and temperatures around 200C (6). This study was undertaken to identify the species of Culicoides biting cattle, the preferred parts of the body, their diel landing and biting activity, and compare the diel activity of the populations attracted to suction light traps with those attracted to cattle. These data were correlated with weather conditions of temperature, relative humidity, wind velocity and direction and cloud cover. The influence of site location and housing of the host on the number of Culicoides collected was also studied. Introduction Results Discussion back to top Materials and Methods The major study was carried out at the ground of the Kimron Veterinary Institute during 11 months from 16.10.86 to 21.11.87. Male Israeli Holstein calves were used as baits. Seven calves from 4 to 10 month old, standing 80 to 100 cm, length 150 to 200 cm and weighing 100 to 300 kg were used. Most of the collections were done on a calf 6 to 10 month old, with mainly black in colour, with an initial weight of 100 kg and Fig. I Collection zones from the body of the bait calf weighing 200 kg at the end of the experiment. There were five collection sites on the calf (Fig. 1). The caged animal was moved to six different sites to find an appropriate location rich with Culicoides spp. Collections were made mainly with a battery operated asprirator (Housherrs' Machine works, N.Y. USA) and to a lesser extent with a mouth aspirator. For illuminating the site of collection, a head lantern covered with red cellophane to avoid disturbance to midges was used (Type 1904 Y. Cell, Justrite Manufacturing, USA). Time of collection was from half an hour before to an hour post sunset and sunrise. Each collection continued for 10 minutes and was followed by a break of 5 minutes. The 90 minute collections at the calendar sunset and sunrise were divided into periods of 30 minute. Twenty-four hour collections were also made to determine the exact biting time. The collected insects were put in saline solution containing detergent for identification. Insects were categorized by species, sex, nulliparous and parous. Suction light trap (11) situated in the center of the cowshed was also operate to compare the composition of the population attracted to the suction light trap in parallel with that collected from the calf. The second purpose was to determine the seasonal activity and the third to determine the diel activity. For the last aim the catch at each hour was sorted according to the above criteria. Host detection: Data from a modified Magoon type (5) bait trap, a Davies trap (12) and a Monks Wood suction black light trap, as described by Braverman et al. (13) in Israel were utilized. In order to learn whether the midges enter the Magoon traps and do not escape, a window frame from which the glass was removed, was covered with strips of organdy cloth, smeared with castor oil and placed inside the Magoon trap to catch the midges. Another type of trap baited with a two week old calf weighing about 50 kg was operated fourteen times between July 16 and December 31, 1978 in Ga'ash (32014'N 34049'E). The trap was situated in an open field at the northeastern side of the village. The trap was a square structure the four sides of which were each comprised of two electrocuting grids (from Matador insect exterminator model 1220, Ga'ash Lighting Co. Israel), from which the black light lamps were removed. The top of the structure was covered with a plastic sheet. Insects had access to the calf through the electrocuting grids. Bait trap data from Harare area, Zimbabwe were also used based on lard-can traps (14); a trap designed by Turner (15) and trappings by a version of the bed-net trap (16). Data on the last trap were reported also by Braverman and Phelps (17). Meteorological data: Minimum and maximum temperatures were taken in Bet Dagan at the collection site near the bait animal. Temperatures, relative humidity (%), cloud cover, wind direction, wind velocity and rainfall for other dates were taken from the monthly data published by the Israel Meteorological Services. The influence of these parameters on the collection from calf with a suction light trap was examined. Statistical analysis: The following tests were used: a. paired t test; b. c2 (Chi square) and c. analysis of variance. The t and F tests were performed on logarithmic transformed data. Results Collections from a calf. Fifty-two collections at six sites located at different places on the farm were made. Of these, site no. V yielded 98% of all the Culicoides specimens. Table 1 shows the numbers of Culicoides spp. collected at the different sites. In the years 1981 to 1982, from January to December, suction light traps were run in parallel at three sites of the animal compound, near a stable, near a calf shed, and near a large cowshed. Comparison of Culicoides spp. numbers collected from these sites show significant differences. At the first site, during 6 light trappings, 1117 specimens of Culicoides spp. were caught versus 30 specimens of Culicoides spp. caught near the cow shed (P< 0.01). From the calf shed, 1208 specimens of Culicoides spp. were caught during 3 light trappings, as compared to 336 specimens of Culicoides spp. caught near the cow shed. (P < 0.05). Thus, significant differences in Culicoides spp. numbers were found between the various collection sites. This agrees with our findings from the calf collections. Of the total number of Culicoides collected from a calf, 522 were C. imicola, 1 C. newsteadi Austen and 1 C. schultzei gp. Thus 95% of the collected midges were found on the back and 5% were found on the flank of the calf (Fig. 1). At both collection areas, most of the females were nulliparous, and 10% of the females collected from both areas were engorged (Table 2). Culicoides imicola clearly preferred to land on the dark than the lighter areas of the calf. Table 1. Collection of Culicoides spp. from a calf in various sites within the animal compound at Bet Dagan (1986/7). Site No. Date I October 22-31.86 0/4 0 II October 22-31.86 0/4 0 III June 20-July 10.87 1/4 2 IV April 23-June 11.87 1/5 3 V July 19-November 21.87 30/34 513 VI October 6-15/87 3/3 6 Total October 16.86-November 21.87 35/52 524 No. of positive collections / total no. of collections No. of Culicoidesspp. collected Table 2. Physiological age distribution of C. imicola gnats collected from the back and sides of a calf (Bet Dagan, 1986/7). Body zone Total no. of nulliparous No. of engorged nulliparous Total no. of parous No. of engorged parous Total % Back (1) 296 29 145 27 497 95 Side (2) 16 1 7 1 25 5 Others (3,4,5) 0 0 0 0 0 0 Total 312 30 152 28 552 100 Diel activity peaks of C. imicola. Collections from a calf over 24 h showed only two peaks, i.e. at sunrise and sunset. Of the 44 sunset collections, 38 yielded Culicoides spp. At sunrise, only 8 collections were made and 7 were positive. The landing and biting activity occured from half an hour before till one hour after sunset. According to the "t" test, the sunrise peak is significantly (P< 0.05) higher than the sunset peak (Table 3). It was found that the proportions of nulliparous, engorged nulliparous, parous and engorged parous of C. imicola, caught at sunset and sunrise, were similar at both times. Statistical analysis (c2) for sunrise and sunset showed no significant dependence between the four categories of female C. imicola and the time periods of 30 minutes. This infers that the fixed proportions between nulliparous, engorged nulliparous, parous and engorged parous are independent of the time of collection. Table 3. Numbers of C. imicola collected at sunset and at sunrise (Bet Dagan. 1986/7). Date of collection Sunset Sunrise Hours of collection No. of midges Hour of collection No. of midges July 19-20 19.20-20.50 0 5.30-7.00 12 August5-6 19.15-20.45 4 5.15-6.45 18 August 12-13 19.00-20.30 6 5.30-7.00 28 August 26-27 18.45-20.15 0 5.15-6.45 29 October 1-2 17.00-18.30 3 5.00-6.30 10 October 20-21 16.10-17.40 19 5.30-7.00 28 Total 32 Figure 2 and statistical analysis show that accumulatively at sunset similar numbers of C. imicola were collected at the first [89] and third [83] time periods, whereas in the second [197] time period higher numbers of insects were collected. At sunrise accumulatively (Fig. 3), similar numbers were collected at the first [78] and second [60] time periods, whereas smaller numbers [6] were collected during the third time period. Statistical analysis for each of the following categories: nulliparous, engorged nulliparous, parous and engorged parous showed similar tendencies. Analysis by c2 showed that the proportions of the numbers of C. imicola collected at each time of sunset and sunrise differed from (P<0.01) 1:1:1. Information on the biting activity of C. imicola could be derived from the analysis of each time period at sunrise and sunset collections during July through December (Fig. 4, 5, 6, 7). Figure 4 shows that the activity of the nulliparous C. imicola at sunset is not stable over the season and is characterized by sharp rises and falls. The following four major peaks are shown: second half of July, first half of September, second half of October and second half of November. The last peak is the highest and reflects the rise which occurred during the three collection periods. The activity of the nulliparous C. imicola at sunrise showed moderate changes compared with changes at sunset. The peak is in August after which there is a moderate decline till October. In this month, there is a moderate rise in 125 the first and third time periods and a sharper rise in the second time period. The activity of parous C. imicola during sunset (Fig. 6) is not fully expressed due to the smaller numbers collected throughout the season compared with the activity of the nullipars (Fig. 4). The parous have three main peaks: first half of August, first half of September and first half of November. The last peak is the longest and highest and reflects the rise in numbers of C. imicola collected in the three time periods. Numerically the peaks of the parous are smaller than those of the nulliparous. The activity changes of the parous C. imicola at sunrise (Fig. 7) throughout the season were more moderate than the changes during sunset (Fig. 6). The parous peak was in August, similarly to the peak of the nulliparous (Fig. 5). Following the peak, there was a moderate decline till October when there was a moderate rise in the second and third time periods, versus a slow decline during the first time period. Fig 2. Numbers of C. imicola aspirated from a calf from July to November in each tertiary period of 30 minutes during sunset in 1987. Fig 3. Numbers of C. imicola aspirated from a calf from July to November in each tertiary time period of 30 minutes during sunrise in 1987. Fig 4. Numbers of nulliparous C. imicola aspirated from a calf in each tertiary time period of 30 minutes during sunset in 1987. Fig 5. Numbers of nulliparous C. imicola aspirated from a calf in each tertiary time period of 30 minutes during sunrise in 1987. Fig 6. Numbers of parous C. imicola aspirated from a calf in each tertiary time period of 30 minutes during sunset in 1987. Fig 7. Numbers of parous C. imicola aspirated from a calf in each tertiary time period of 30 minutes during sunrise in 1987. The influence of meteorological factors on the biting activity of C. imicola The comparison of the meteorological data with the numbers of collected midges showed a significant association only with the daily maximum temperature. The peak of activity occurred when temperatures were between 20 to 24oC and activity continued up to amaximum daily temperature of 34oC (Fig. 8). The regression equation on the association between the numbers of Culicoides (tot) and the maximum temperature (t.max): tot = 82.04 - 2.30 * t.max. with r2 = 0.38 (P< 0.0008). No collections were made on rainy days. Fig 8. Numbers of gnats aspirated from a calf plotted against the maximum temperature. Suction light trappings a. The diurnal activity of Culicoides spp. as measured by suction light trappings Only few Culicoides spp. were caught during daytime operation of suction light traps. Similarly 40 daytime trappings at the animal compound of the Veterinary Institute were carried out in 1978 to 1979, and only in 5 trappings 11Culicoides were caught: 6 C. imicola, 4 C. distinctipennis Austen and 1 C. circumscriptus Kieffer. In the present study, the suction light trap was operated over 38 nights and Culicoides were caught each night. Seven of the trappings were done in 1986. A total of 10,257 Culicoides spp. were caught, out of these 285 (2.75%) were males. Seven species were caught (Table 5), the principal one was C. imicola which constituted 98.5% of the catch. These findings are parallel to the collection from the calf, where C. imicola was also the principal species. b. Average monthly catch of C. imicola The numbers of C. imicola during April through November 1987 grew gradually till the peak in September Fig 9. Monthly abundance of C. imicola (autumn). In October-November a marked decrease in their numbers occurred (Fig. 9). Similar activity was seen in 1969, when the autumn peak continued over 4 months i.e. August to November (Fig. 10). c. The peak hours and the diem activity of Culicoides spp. as measured by suction light trappings Hourly night trappings were conducted in May to November 1987 over 10 nights. The catch from each hour was sorted and identified. A rise in the number of Culicoides was found during the night and the sharpest increase occurred in July-August between the seventh and eighth hours of darkness (2:00-3:00). In May-June the peak was between the eighth and ninth hour at 2.30 a.m. to 4.30 a.m.; in July to August, at 3.00 to 5.00 a.m.; 1.30 to 3.30 a.m. in October and 12.30 a.m. to 2.30 a.m. in November. Following the peak, there was a sharp decrease at the eleventh hour (of darkness) i.e. 5.00 to 6.00 a.m. in JulyAugust (Fig. 11). The major component of the population was nulliparous and parous females, whereas in decreasing order were: engorged nulliparous, engorged parous and males. Engorged females were caught throughout the night, with a peak at the eighth and ninth hours. A significant (P < 0.0003) difference was found in the activity of the various categories of females (nulliparous, engorged nulliparous, parous and engorged parous) throughout the 12 hours of night trapping. d. The influence of meteorological factors on the flight activity of Culicoides spp. as measured by suction light trappings By correlating the meteorological data with the number of Culicoides spp. caught by the suction light trap throughout the season, a significant (P<0.0001) association was found only with the minimum daily temperature (Fig. 12). Host detection: Using bait traps originally designed for mosquitoes, between March to October 1978 at Bet Dagan yielded only small numbers of Culicoides spp. (Table 6). Fig 11. Numbers of gnats suction light trapped according to five categories: M, males; P, parous; PE, parous engorged; N, nulliparous; NE, nulliparous engorged. Fig 10. Monthly abundance of C. imicol Fig 12. Numbers of gnats suction light t minimum temperature. Table 4. Distribution of the physiological stages of C. imicola collected at sunrise and at sunset. Time Period of Collections Sunset Nulliparous Nulliparous Parous Parous engorged engorged 1st 58 4 23 4 catch % 65 4.5 26 4.5 2nd 124 10 51 12 catch % 63 5 26 6 3rd 53 7 18 5 catch Total 89 Nulliparous Nulliparous engorged 37 5 Sunrise Parous Total 29 Parous engorged 7 Nullipa 78 95 100 197 47.6 31 6.4 4 37 25 9 0 100 60 57 155 100 83 51.7 4 6.6 0 41.7 2 0 0 100 6 60 57 % Total % 1 64 235 64 8 21 5.5 22 92 25 6 21 5.5 100 369 100 67 72 50 0 9 6.25 33 56 38.8 0 7 4.95 100 144 100 64 30 60 Each collection lasted 90 minutes divided into three 30-min segments. Table 5. Culicoides spp. light trapped at the veterinary institute in the years 1986/1987 Month/year 10/86 11/86 12/86 4/87 5 1 1 1 No. of trapping operations Species Total No. of Average Total No. of Average Total No. of Average Total No. of Average Total No males per night males per night males per night males per night ma C. imicola 1389 28 277.8 124 0 124 6 0 6 C. schultzei gp 37 12 7.4 1 0 1 1 0 0.25 14 0 3.5 C. newsteadi C. puncticollis 1 Becker C. circumscriptus Total 1426 0 40 0.25 285.2 2 0 124 6/87 7/87 No. of trapping- 5 4 Species Total C. imicola 1076 No. Average Total of per night males 35 215.2 1809 C. schultzei gp 4 0 0.8 C. newsteadi 1 0 0.2 C. puncticollis 14 0 2.8 C. circumscriptus C. obsoletus Meigen 1 0 0.2 1 0 0.2 Total 1098 35 219.6 Month/year 14 1823 124 7 0 7 15 0 3 2 0 3.75 99 5 10/87 6 1 3 No. Average Total of per night males 38 452.25 2826 No. Average Total of per night males 67 471 740 No. AverageTotal of per males night 21 740 1563 No. of males 41 5 0 3 0 3 14 3 14 2 14 4 0 1581 44 3.5 455.75 7 1.2 2 0 0.3 1 0 1 2835 67 472.5 758 23 758 11/87 Total 3 Total 2 9/87 43 8/87 No. of trapping operations Species 3 0.5 0 Month/year 91 No. of 37 Average Total N C. imicola C. schultzei gp 469 6 males 28 0 per night 156.3 2 C. newsteadi C. puncticollis 16 0 5.3 10107 87 38 17 C. circumscriptus 4 C. obsoletus C. cataneii Clastier 4 1 491 Total 28 163.6 10257 Table 6. Live and chemical baits used in various traps in order to catch Culicoides spp. in Israel in 1978.. Locality Trap type Trap position Bait Bet Dagan Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap On the ground 4-13 chickens Period of trappings operations March-June Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Palmahim Palmahim Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap Modified Magoon trap No. of trap operations Culicoides spp. t 9 4 On the ground 2 turkeys August-September 3 0 On the ground 1 calf March-June 12 2 C. circunscr June 2 1 0 C. sp. On the ground 1 calf On the ground 1 calf and 2 turkeys On the ground 1 sheep June 4 0 June-September 12 0 On the ground 1 calf, 1 sheep and May-September 6 0 10 0 6 0 May-June 2 0 August 3 13 C. circumscr 4 2 C. imicola 3 C. circumscr C. imicola 2-3 turkeys On the ground 1 sheep and 1-2 July-October turkeys On the ground 4 kg dry ice May-June On the ground Ammonia (NH4OH) 5% Hung on pole Monks wood inside the suction black modified Magoon traplight trap Hung on pole inside the Monks wood suction black light trap with dry ice On the ground 1sheep and Monks wood black light trap August August 1 1 C. distinctipe 1 Bet Dagan Bet Dagan Bet Dagan 1 Davies (1973) trap Davies (1973) trap Davies (1973) trap Hung on pole on tree Hung on pole on tree Hung on pole on tree Palm dove March-August 7 1 1 C. circumscr Guinea pig March-August 7 1 C. circumscr 3 kg dry ice June-Julyt 2 1 C. circumscr All Culicoides trapped were females. Magoon trap baited with chickens caught four C. distinctipennis on March 28 and April 4. A frame with organdy cloth smeared with castor oil used in one operation with the chickens did not collect any Culicoides. A calf used as bait caught two C. circumscriptus and one unidentified Culicoides on March 21 and April 17. A frame covered with organdy smeared with castor oil which was operated three times with a calf did not catch Culicoides spp. Magoon trap baited with a sheep, mixed hosts of a calf, a sheep and turkeys, sheep and turkeys; and the attractants; 4 kg dry ice and 5% ammonia, yielded no Culicoides spp. An organdy frame with castor oil was used three times together with dry ice failed to trap any Culicoides. Monks Wood suction black light traps without any additional bait, were operated 3 times inside the Magoon traps. In addition a similar trap plus dry ice and another one together with a sheep were operated. With these 16 C. circumscriptus, 8 C. imicola, 3 C. distinctipennis, 2 C. schultzei gp., 1 C. newsteadi and 1 C. odiatus Austen were caught, i.e. five times more than with animals alone as baits during eight months. Davies trap baited with a palm dove (Streptopelia s. senegalensis) caught on June 20, only 1 C. circumscriptus. On July 4, 1 C. circumscriptus was caught in a trap baited with a Guinea pig. On July 20, Davies trap baited with dry ice, caught 1 C. imicola. Only Culicidae and no Culicoides spp. were caught at the bait trap in Ga'ash. In Zimbabwe (Table 7) lard can traps baited with a rabbit, two guinea pigs, pigeon and dry ice, hung on trees in various positions and laid on the ground, yielded no Culicoides spp. During the same period lard can traps baited with chickens caught C. milnei Austen on two occasions. A single female was caught on January 5, and three females were caught on May 3 on the castor oil smeared funnel from which the carnivore protecting net on the opening was removed (Table 7). Turners' (15) trap baited with a chicken caught Culicoides spp. on four occasions: 30-31.3.77; 31.3.-1.4.77; 12-13.4.77 and 2-3.5.77. The catch on the first date was the largest and comprised 25 C. imicola and 8 C. milnei. Three of Turner's trap (15) of the four operations were conducted at a site richer in Culicoides spp. In all four operations that yielded Culicoides spp., castor oil was smeared on the strips of the muslin cloth and also on strips of muslin cloth that were put over the chicken restrainer. The Culicoides specimens were actually collected from the smeared cloth. Bed net trap baited with a calf caught 12 Culicoides specimens which is the largest number when compared to 6 and 2 Culicoides specimens caught in a similar device baited with human and sheep respectively. Table 7. Culicoides spp. collected in live and chemical baits used in various traps in Harare area, Zimbabwe (1976-1977). Trap type Position of the Bait trap Period of trappings No. of trap operations Culicoides spp. trapped1 Lard can Hung 1 rabbit horizontally on tree vertically and on the ground 28.10.765.4.77 43 0 Lard can Hung 2 guinea pigs 15.2-18.2.77 horizontally on tree 3 0 Lard can Hung on tree horizontally and vertically Lard can Turner, 1972 1 chicken 3.11.76-4.5.77 57 4 Hung 1 pigeon horizontally on tree dry ice 28-29.10.76 1 0 18-19.1.77 4 0 Hung on tree 1 chicken and on ground 11.3-5.5.77 20 37 C. inicola 16 C. milnei Turner, 1972 Turner, 1972 18-19.3.77 1 0 Bed net Hung 1 rabbit horizontally on tree On the ground 1 sheep 22.12.7625.2.77 10 1 Bed net On the ground 1 calf 14.3-24.3.77 7 1 7 3 1 1 Bed net 1 On the ground 1 human 4.3.-12.3.77 2 4 1 1 C. milnei C. milnei Ingram & Macfie C. pycnostictus C. milnei C. imicola C. nivosus De Meillon C. zuluensis De Meillon C. minei C. imicola C. fulvithorax Austen All Culicoides trapped were females. Discussion a. The preference of Culicoides to the calf site High numbers of Culicoides midges were aspirated on one out of six site locations of the calf. At the same time the suction light trap caught Culicoides spp. near five negative sites. This indicates the existence of a factor(s) that hampers detection of the host by Culicoides. The known major host attraction parameters are: temperature, humidity, scents and sight of the host. It is assumed that host's temperature in summer was similar at all collection sites as all were done at the same time, and mostly from the same calf. Site II, from which no Culicoides spp. were collected, was close to a large cowshed and the midges were probably attracted more to the animals in the cowshed emitting more attractants. Even when the calf was put inside the same cowshed (site III), only two Culicoides specimens were collected. Culicoides might be more attracted to older and larger animals. At site IV, three Culicoides spp. were caught where the calf was put inside a citrus grove. The trees might have hidden the host from the midges. This finding is in accord with a study in Alabama (10) where it was shown that 2.5 fold more Culicoides specimens were collected from a host situated in a field than from one situated in a wooded area. Most Culicoides spp. were collected from site V which was situated in an open area that could be seen from most sides. Site VI, like site V, was situated in an open area and indeed Culicoides spp. were collected from the bait animal in smaller numbers. The smaller numbers of Culicoides specimens from site VI is probably due to the distracting light from a lantern situated nearby, and/or air turbulence which disturbs landing of the biting midges on the calf. In this case it seems that visibility of the animal was the determining factor. In the negative sites, the trees and/or animal houses shaded and obscured the calf from the Culicoides spp. The fact that C. imicola preferred to land on the dark haired areas of the body, avoiding the white ones, shows that even at twilight time and darkness the midges like mosquites can distinguish between different light and/or temperature intensities (18). Intense shadowing at the negative sites might have prevented the Culicoides spp. from finding the calf. The fact that houses and trees interfere with the orientation of Culicoides spp. to their hosts, can explain the seemingly erratic transmission of bluetongue or other Culicoides-borne pathogens, when one farm is infected while a nearby farm is not. It can be concluded that the location of the animal house, related to its exposure to Culicoides spp., can influence pathogen transmission by midges. b. C. imicola preferred landing and biting sites on a calf In collections made directly from the calf, the major species was C. imicola which also constituted 98.5% of the Culicoides spp. population caught by the suction light trap. It was found that C. imicola prefers to land and most probably bite the back, especially the dark haired areas, and avoids the white ones. Landing preference of C. imicola on the back was already described in a horse (19). This finding strengthens the assumption that C. imicola behaves similarly to the Australian species C. brevitarsis which also prefers to bite the dark areas along the back of the cow (6). c. The diel biting cycle of C. imicola Many species of Culicoides prefer to bite mainly at crepuscular time (8,20). Little information was published on the biting habits of C. imicola. According to Braverman (19) a peak biting time occurs at sunset, sunrise was not previously checked however. The present study shows a greater peak at sunrise than at sunset. d. The association between light intensity and C. imicola activity Monitoring the numbers of C. imicola caught at each time shows an increase towards sunrise or sunset confirming the finding that biting activity is associated with changes in light intensity. At sun-rise, there is a sharp drop in the numbers of collected midges with full daylight. The numbers of C. imicola collected at the first and third time periods of sunset is similar probably because in the first time period is too much light, and in the third time period it is too dark. Largest numbers of C. imicola were collected at the second time period, when the highest changes in light intensity occur. e. Hourly flight activity of C. imicola as measured by a suction light trap The peaks of activity observed in April-June, July-August, October and November were similar to those found in South Africa (3).Temperature and relative humidity (%) seemed to be the factors that determined the time of peak flight activity of Culicoides spp. During the hottest months of July-August, the air temperature drops only between 3.00 to 5.00 A.M to its optimum for Culicoides spp. when there is the highest relative humidity. In November the temperature between 3.00 am and 5.00 am is too low for flight activity and therefore the optimum for flight is between 00.30 anm and 2.30 am. For C. sonorensis in southern California it was found that the peak flight activity in October and November occurred at 0-3 h after sunset (21). At this time of the year, relative humidity is high throughout the night. A constant hourly ratio of nulliparous and parous female Culicoides was found throughout the sampled nights. This was in contrast to the different patterns of hourly flight activity in the various categories of females reported elsewhere (4). Constant hourly ratios between nulliparous and parous for each night sampled were similarly found throughout the insect season. In this study, as in previous ones (2, 4) it was found that the ratio of parous C. sonorensis and C. imicola was greater towards the end of the season. The unmatched peaks of the suction light trap and the direct collection from the calf indicated that the two trapping methods collect different populations of the same species. The non-biting population of C. imicola in the suction light trap has a different flight peak than the biting population collected from the calf. f. Host detection The paucity of Culicoides spp. entering the modified Magoon and Davies (12) traps together with the absence of Culicoides in the castor oil frame inside the modified Magoon trap eliminates the possibility that Culicoides spp. might have entered the trap and eventually found their way out. Also the visible attraction source, i.e. Monks Wood suction black light trap, positioned inside the modified Magoon trap, caught five times more Culicoides spp. than those caught during the entire period by animals and chemicals used as baits, demonstrates the significance of sight in host detection. Indeed showing the importance of sight for host detection by mosquitoes, enabled Klowden and Lea (22) to construct their bait trap with a transparent Plexiglass cover. These findings show that Culicoides spp. actually see the animals in their host detection trials. In Zimbabwe the lard can bait trap which hid the animal prevented its detection by Culicoides spp. Three out of four C. milnei, probably attracted by the smell of the chicken bait, were picked off the castor oil smeared on the opening of the trap. The only bait trap used in the entire study, especially designed for trapping Culicoides spp. was Turners' (15) trap. In Virginia, Turner caught eight Culicoides species with no details on the numbers trapped (15). While in 21 catching operations, carried out in Zimbabwe, between March-May 1977, only 37 C. imicola and 16 C. milnei were caught (15). Out of the total 53 Culicoides specimens at least 18 were collected from castor oil smeared surfaces of the trap. There is an indication that some of the Culicoides spp. found their way out and it is evident that the trap was not effective in trapping the Culicoides spp. in the study area. The Magoon bed net trap with each of the three baits collected only few Culicoides spp. Though castor oil was not used in this case it is assumed that the small numbers of Culicoides spp. caught was due to the midges not detecting the bait, rather than their entering and escaping through the opening. The least attractive bait was a sheep and the most attractive was a calf luring 6 times more Culicoides midges than the sheep. This host preference was previously recorded (7, 13). g. The effect of meteorological factors on Culicoides spp. activity Relative humidity, wind velocity and direction and cloud cover are known to exert influence on Culicoides spp. activity, but no such influences were detected in this study. This might be due to not collecting meteorological data at the collection sites and not at the times of collections and trappings. h. Importance of the findings Biting time activity of Culicoides spp. is short and limited to sunrise and sunset. As C. imicola prefers the back of the animal, it can be simply controlled by clock operated foggers installed on turntables and programmed to spray a repellent during the biting time periods. Back dusters or smearers of repellents can also be used. Such control methods might minimize the risk of contracting Culicoides borne pathogen in bovine insemination and ova collecting centers as well as livestock exporting farms. Host detection by Culicoides imicola seems to depend primarily on sight. Culicoides rarely penetrate shaded closed barns. At times of outbreaks of Culicoides-borne diseases such as bluetongue, Akabane, African horse sickness and bovine ephemeral fever, susceptible animals housed in a close barn (not a shed) will be relatively protected. LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE References 1.