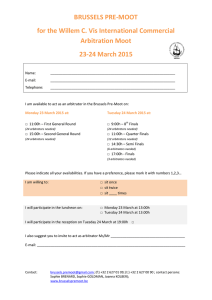

III Research Workshop on Philosophy of Biology and Cognitive

advertisement

III Research Workshop on Philosophy of Biology and Cognitive Science Full Programme THURSDAY 4 APRIL 09.30-11.30h Matteo Mossio (CNRS) Biological complexity and its evolution Abstract: In this talk, I will argue that biological complexity can be characterized in a relevant way as organized complexity. Organized complexity supposes what I will call closure, i.e. a specific causal regime in which the constituents of a system (1) depend on each other for their production and maintenance and (2) collectively contribute to determine the conditions at which the whole system can exist. As claimed elsewhere, closure constitutes a naturalized grounding for functionality: accordingly, it will be my contention that organized complexity implies functional complexity. How does organized complexity evolve? I will claim that the evolution of biological systems results from the interplay between organization and selection: organization channels selective forces, and selection drives organization towards an increase in complexity. Hence, in contrast with mainstream evolutionary thinking, I will suggest that biological complexity cannot be adequately understood uniquely as the outcome of evolution by natural selection: in fact, “many things in biology make sense regardless of evolution”. In fact, organization is a condition, and not just a result, of selective processes. 11.30-12.00h COFFEE BREAK 12.00-13.00h Elsa Muro (Universidad de Navarra) An organizational account of the genome function Abstract: Post-genomic research has modified our understanding of how genome structure supports genome function, challenging the modern concept of the gene as a structural and static unit. New definitions of the gene have been proposed, which conceive of the gene as a functional and dynamic unit. In this paper I summarize a number of these “dynamic gene concepts”, such as Griffiths and Neumann-Held’s concept of “gene as a process”, Keller and Harel’s concept of “genetic functor” and Griffiths and Stotz’s concept of genes as “things an organism can do with its genome”. There are two crucial consequences of these definitions: i) the same part of the genome can be a gene in a particular space and time, and a different gene in another particular space and time; ii) there is a circular causal regime governing genes. I propose a revision to these dynamic gene concepts by conceptualizing the genome function from an organizational perspective, rather than from the earlier perspectives proposed (selected‐effects and causal‐role accounts). The reason is that, on the one hand, a circular causal regime is essential in an organizational theory of biological functions, and, on the other hand, this theory is very close to a process metaphysics. I apply Schlosser’s organizational account (1998) because his definition of functions includes temporal indices and can deal smoothly with the multi‐functionality of traits, so that it emphasizes the independence of functions from structures. 13.00-14.00h Cristian Saborido (UNED) Natural norms beyond the oxymoron Abstract: In this communication I consider the problem of the theoretical grounding of the notion of natural normativity for the naturalistic perspective. I present the current debate on this issue in philosophy of biology in which there are some attempts to ground natural norms on the notion of biological function. I claim that these attempts interpret biological normativity in a specific way different from the classic philosophical interpretation of normativity. This functional interpretation of norms presupposes an inherent normative dimension in the biological behaviour that is able to overcome the problems identified by the formulation of the naturalistic fallacy. Here, I argue in favor of this interpretation of natural norms offering arguments for overcoming the classic philosophical "is-ought" distinction regarding functional biological normativity. However, I hold that the mainstream account in the debate on functions, i.e. the evolutive-etiological approach, is not able to ground the ascription of natural norms in a valid way and I defend that a different functional approach, grounded in the biological properties of the organization of living beings, is necessary to offer an adequate naturalistic account for biological teleology and natural normativity. 14.00-16.00h LUNCH BREAK 16.00-17.00h Víctor Luque (Universitat de València) Between Newton and Boltzmann: structure and causality in the theory of evolution Abstract: Una nueva visión de la Teoría Evolutiva se ha desarrollado en esta primera década de nuestro siglo, desafiando el consenso general –tanto entre biólogos como entre filósofos– que la entendía como una teoría de fuerzas. Denominada de diferentes formas (interpretación estadística; interpretación epifenomenalista; interpretación estadística emergentista), es defendida por un número muy reducido de autores. Para éstos, el proceso evolutivo y sus diferentes partes (selección, deriva, migración, mutación, etc.) son un resultado meramente estadístico, inseparables unas de otras. De este modo, la selección natural o la deriva deberían entenderse como una tendencia estadística a nivel poblacional, abandonando cualquier pretensión de rol causal de éstas. Esta nueva visión nos obliga a (re)evaluar la analogía de la teoría evolutiva con la mecánica newtoniana para poder vislumbrar tanto sus aciertos como sus posibles inconvenientes. 17.00-18.00h Argyris Arnellos (Universidad del País Vasco) Multicellular autonomy and behavioral agency Abstract: In this talk I’ll begin by examining the property of motility as demonstrated in a case of early eukaryotic multicellular (MC) system. In particular I’ll focus on the relation between the organization of its body plan and the way this organization supports motility-based interactions with the environment, and I shall argue that such biological MC organizations do not exhibit adaptive behavior. Next, I suggest that adaptive behavior requires a completely new and qualitatively different MC organization characterized by the integration of neuro-musculoskeletal structures and of functionally differentiated organs organized in various body plans so that MC systems can meet the respective metabolic and biomechanical needs. In turn, I argue that the basis of adaptive behavior lies in the kind of developmental organization able to support the functional differentiation and integration of such MC systems. I continue by explaining in detail the nature and the characteristics of the respective developmental organization and I argue that it results in a type of functional integration, according to which the MC system’s action is integrated with its functional construction. Finally, I conclude by suggesting and explaining why MC systems exhibiting this type of developmental organization should be considered as behavioral agents. FRIDAY 5 APRIL 09.30-11.30h Hong Yu Wong (Universität Tübingen) Action as flexible behaviour Abstract: In this talk I will argue that we should characterise action as a distinctive kind of flexible behaviour. I will argue this from considering the contrast between actions and reflexes. Following this, I will argue that the operation of the motor system is partly constitutive of the flexibility of action. This requires that I argue that the operation of the motor system cannot be seen simply as an enabling condition for bodily action. This commits me to disagreeing with all major accounts of action in the philosophical literature. Along the way we will explore some unusual cases of actions, such as sub-intentional actions (O'Shaughnessy 1980) and stimulusdriven actions (Prinz 1997), which provide grounds for flexibility as the criterion for agentive behaviour. The unifying theme will be that all extant accounts either failure to capture the intrinsic agentive character of bodily action (the standard causal accounts from Davidson and followers) or capture this in terms of agency being a self-conscious capacity (Thompson, Vogler). 11.30-12.00h COFFEE BREAK 12.00-13.00h Manuel Heras (Universidad de Granada) Natural norms: a Wittgensteinian approach Abstract: In this talk I want to challenge the notion of ‘normativity’ developed by the autonomous systems theory or also the contemporary enactive approach to cognition (even when both approaches are slightly different, I will expose the common assumptions underliying both approaches). First, I will define the varieties of enactivism and their assumptions and then I will expose the reasoning for the co-emergence of individuality and normativity within the enactive or autonomous framework. Second, I will criticize this notion in two steps: (1) showing why introducing dispositions for explaining certain processes of living beings can be more useful than claiming that all processes in living beings are normative, and (2) showing how Wittgensteinian arguments on norm-establishing and norm-following can help to prove that this enactive approach is not explanatory enough for understanding which is the role of normativity in nature. Then I provide my own point of view on how the naturalization of normativity should be addressed in a general theory of biological processes. 13.00-14.00h Alex Díaz (UNED) and María Muñoz (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) Artifact-grounded perception Abstract: Everyday perception may involve the use of artifacts. From glasses to sophisticated technical aids, they all constitute a wide range of objects that modify our interaction with the surrounding world, making it more accessible to us. But, what is that form in which artifacts modify our interaction? One might think that perceptual artifacts are characterized by correcting or providing incoming information for an organism: glasses give you defined retinal images, hearing aids amplify sounds, etc. However, many artifacts can provide information about the surroundings: a thermometer is providing users data about the environment, but the agent's experience of interacting with a thermometer is from a totally different kind of that of wearing glasses. Where is this difference grounded? We will try to show how perceptual artifacts, at the same time that they establish as sets of constrains for perception and action that make some information more easily available, they provide users with much more than raw sensory information, they become transparent to the user if some conditions are matched (Ihde, 1990). Perceptual artifacts, when coupled with the agent, are not elements of the perceptual field, but rather constitutive of it: once coupled they do not constitute a set of affordances to perceive, but actually they afford perceiving new affordances of the world. We will illustrate our presentation with the description of the TSIGHT (Cancar et al., in press), a sensory substitution device: an artifact designed to provide blind people with distance-based information in the form of vibrotactile stimulation. It consists of a wear-on-able Kinect camera capturing distances that are translated into vibration intensities displayed by a matrix of 78 motors attached to a elastic waistband to be worn on the torso. Information is fully contingent to user's movements. Based on the study of the TSIGHT, we will draw some reflections on the nature of perceptual artifacts. 14.00-16.00h LUNCH BREAK 16.00-17.00h Javier González de Prado (UNED/University of Southampton) The indispensability of metaphor versus the algorithmic mind Abstract: In this paper I argue for the possibility that metaphor may be indispensable for having and expressing certain contentful thoughts. I defend this possibility against the objection that, if metaphors express contentful thoughts, these thoughts should be specifiable by literal means. I argue that this objection loses its strength if we adopt a view of language and thought according to which understanding a sentence or grasping a thought requires mastering a suitable skill, which in general would not be characterizable by rules or step-by-step algorithms (Travis, 2000). In metaphorical speech and thought, this skill would involve being able to appreciate relevant mappings between different domains. Thus, the capacity to make these salient metaphorical mappings would be an indispensable requisite for having and expressing certain thoughts. 17.00-18.00h Krisztina Orban (University of London) Is 'immunity to error through misidentification' immune to counterexamples? Abstract: In my talk I will consider some putative counterexamples to immunity to error through misidentification (IEM) based on unusual experiences. My aim is to show that these cases are not counterexamples to IEM, contrary to what some theorists have claimed. The putative counterexamples to IEM are: inserted thought (Campbell 1999), the body swap illusion, and somatoparaphrenia (Lane and Liang 2011, drawing on Petkova and Ehrsson 2008 and Vallar and Ronchi 2009). What IEM is can be introduced by two examples: a thought which is IEM and a thought which lacks IEM. When I think a thought T1 ‘I have my legs crossed’, based solely on proprioception, I cannot misidentify who/what has her legs crossed. Thus T1 is IEM. In contrast, when I look at the mirror and based on that I think a thought T2 ‘I have my legs crossed’, then I can misidentify who has her legs crossed. Thus, T2 is open to an error of misidentification. Note that the basis has to be specified because the same thought might be IEM made on one basis, but not IEM when made on another basis. The counterexamples try to show that a thought that is supposed to be IEM is not IEM. To work, the counterexamples have to show that a supposedly IEM thought (like ‘I have pain’) loses its IEM in certain situations even though the basis of the thought remains the same. However, the discussion of these putative counterexamples in the literature lacks any specification of the basis of the thoughts. In order to discuss them, we first strengthen some of the putative counterexamples by adding this necessary element to it. Next we argue why they fail to be counterexamples. Against Campbell’s counterexample, inserted thought, a positive symptom in schizophrenia, I argue that even if it were a counterexample, it would be a counterexample against guaranteed right reference of the first person pronoun and not against IEM. Concerning somatoparaphrenia, I agree that it might be a counterexample to another of Shoemaker’s claims but not to IEM. Somatoparaphrenia describes a symptom where the patient disowns part of her body. However, since the pathology is restricted to part of the body (and not the whole) it cannot pose a challenge to IEM. Somatoparaphrenia, however, is inconsistent with Shoemaker’s assumption that a subject’s awareness of pain cannot be decoupled from the subject’s awareness that pain is instantiated in the subject herself. Against the body swap illusion I will use several different strategies. First I will show that the basis of the thought matters for IEM; second, I will undermine some of the results of the experiments; and third, I will question whether ownership means what it says. (1) I will show that the body swap illusion is based on vision (understood broadly) similarly to T2 and not solely on introspection as T1 is. (2) I will show that ownership of the body is best understood as place--‐holder for a disposition of the subject to integrate information to a holistic body image or body schema. (3) I will argue that the body swap illusion has nothing to do with the self--‐ascription of mental states; furthermore, to think that healthy subjects can misattribute another’s mental states to themselves when experiencing the body swap illusion is at best a category mistake.