Constructing the Other X

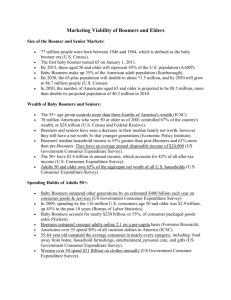

advertisement

Constructing the Other X Kristin Miller Professor Michael Goldberg BLS 461 March 13, 2000 Miller 1 Constructing the Other X In the early nineties, I heard the term “Generation X” for the first time. In both newspapers and magazines the story was that these people, the newest group of young adults— the “twentysomethings” —were lazy, unmotivated, and noncommittal slackers. The images that accompanied the story were of young adults in torn jeans, flannel shirts, and Doc Marten boots, or purple hair, tattoos, and body piercings. Hearing these allegations and seeing the images, I remember thinking, who is the media talking about? My answer was not me, and not my friends. At the time, I was in my early twenties; I didn’t wear torn jeans, didn’t own a pair of Doc Martens, and certainly didn’t have purple hair. I was working full time, going to college, and just barely getting by sharing an apartment with a friend. I was more than willing to commit to a long-term relationship and even marriage someday. Sure, I knew people who had chosen to deliver pizzas or bag groceries instead of going to college. People who would rather spend the day at the lake or ride their mountain bike instead of working a 9-to-5 job Monday through Friday. But even so, those people were not lazy, they were just different, they did what they wanted and didn’t care about making a lot of money or driving an expensive car. Overall, the majority of the people were like me, they attended college, worked hard, and looked forward to starting careers, attaining financial security, and getting married. Therefore, I wondering what the media’s motive was for accusing me, and my generation of being lazy, unmotivated, and noncommittal. I also wondered who was doing the accusing. Examining magazine articles published between 1990 to 1995, the answers are clear; the Baby Boomers were making the accusations about Generation X as a way to start a generational war. In the early nineties, the Boomer run media focused its attention on white, middle to upper Miller 2 class people aged 20 to 25, because they were the largest1 and most educated group2 to enter the work force since the Boomers in the sixties. Since the sixties, the Boomers had been the largest, best-educated, and most powerful group in America. They were the ones who revolted against their parents, participated in “The Movement,” and presumably, changed the world for the better. By the nineties, these same white, middle to upper class Boomers, then in their forties and fifties, were the dominate elite running corporate America. Therefore, when the Boomers realized that Generation X was as large and educated as their generation, they perceived the younger Xer’s as a threat to their jobs, lifestyle, and status. Generation X was similar to the Boomers in race, class, and size, but different in age, appearance, and technological savvy. Because of their similarities, the Boomers recognized the Xer’s as familiar, but at the same time strangely different. This “uncanny” recognition, or gap between their similarities and differences, lead the Boomers to feel estranged from Generation X (Wald, 7). Due to feelings of estrangement, the Boomers began to fear Generation X, and out of fear of losing their status as dominant elite, visualized the Xer’s as alien “others” (Bhabha, 66). Due to their “uncanny” recognition of Generation X, the Boomer run 1990’s media, intentionally created a faulty discourse to make Generation X categorically strange “others.” They attempted to do this by negatively and inaccurately denouncing Generation X’s work, culture, and marriage habits, and in doing so, revealed their fears and anxieties of losing their power, lifestyle, and youth status to the younger, and more recently educated Generation X. As members of Generation X entered their twenties, graduated from college, and entered the workforce, the Boomer elite began to feel anxious about the younger group. Sensing competition from this strangely familiar white, middle to upper class cohort, the Boomers experienced a sense of what Sigmund Freud calls the “The Uncanny.” 3 Drawing on Freud, Miller 3 Priscilla Wald explains that “anxiety [or estrangement] . . . grows out of the transmutation of something ‘known of old and long familiar’ into something frightening” (5). Wald further explains that the uncanny becomes paradoxical when a person, for example a Boomer, “recognizes the stranger [or youth], whose appearance he dislikes, as himself . . .” (7). Paradoxically, the Boomer “discovers that the unfamiliar is really familiar (the stranger as self) but also that the familiar is unfamiliar (the self as stranger)” (7). In terms of the Boomers, the new youth group was similar in size, race and class, but frightening in age, knowledge and appearance, which made them “uncannily” familiar, while “strangely” different. The result of the Boomers uncanny recognition was one of indignation and fear, which they evidenced through their efforts to deal with their mounting anxiety. Fearing that Generation X posed a threat to their jobs, lifestyles, and dominant positions in society, the Boomers deemed the group alien “others.” Because Generation X was similar in race, class, and size, the Boomers recognized their potential to challenge their way of life. As a way to limit the perceived threat of Generation X, the Boomers, as many dominant groups have done in the past, created and used stereotypes to identify and subjugated the group as “others.” In The Location of Culture, Homi K. Bhabha explains the rationale behind this stereotyping strategy when he states: “stereotypical discourse . . .inscribes a form of governmentality that is informed by a productive splitting in its constitution of knowledge and exercise of power” (83). Additionally, to ensure the marginalization of the “other,” Bhabha says, “the stereotype, must always be in excess of what can be empirically proved or logically construed” (66). Thus, to safeguard their position of power and suppress their successors, the dominant Boomer group attempted to establish demarcations between the two generations by negatively and excessively typecasting Generation X. But before we examine exactly what the Boomer media said to make Miller 4 Generation X alien “others,” we must consider how and why the Boomers came to perceive themselves as a powerful and dominant group in the first place. While in their teens, the group of people born in the early years of the baby boom4 were recognized by the media as a large and marketable youth group. By the mid 1950’s, marketers and mass media began noticing the Baby Boomers’ size and financial resources, and concluded that Boomers and youth culture were marketable commodities. Consequently, the Boomers became the target audience for the elder produced film, television, literature, and magazine markets. And to say that these industries made money off the boomers is an understatement. They made a killing! However, while they were making that killing they were also filling the Boomers with mixed messages about rebelling against and conforming to their parents’ values and social expectations. In her book, Where the Girls Are: Growing up Female With the Mass Media, Susan J. Douglas recalls the media’s role in sending such contradictory messages. She says, “the media market was not national and united—especially, but not solely, by age. Even so, media executives tried to please simultaneously the ‘lowest common denominator’ [the middle to upper class parents] and the more rebellious [youth] sectors of the audience, often in the same song, TV show, or film” (15). Coupled with a tenuous parental belief that their children were out of control, these mixed messages played a part in creating a generational gap between the Boomer children and their parents. In effect, it was with the help of the mass media that the Boomers first envisioned themselves as a powerful group. Recognizing their potential to unite and escape their parents limiting bourgeois lifestyle, the Boomers began to think in “dualistic”5 terms of “black and white” and “we and they.” Engaging in this dualistic process, the Boomers began to consider their parents “others.” It was with the steadfast awareness of a generational gap and the Miller 5 knowledge that they were a large and visible youth group that the older portion of the boom generation entered the 60’s and took on the missions of refusing their parents’ “system” and changing it forever. During the 1960’s, many youthful Boomers admonished their parents’ bourgeois values, mourned for President John F. Kennedy, distrusted the government, felt betrayed by Vietnam, and constituted the “anti-authoritarian counterculture movement” (Mitchell xxi). The Boomers who shared these feelings became part of “The Movement,” which Terry H. Anderson says: connotes all activists who demonstrated for social change. Anyone could participate: There were no membership cards . . . .[The] Activists defined and redefined their movement throughout the era. In the early years demonstrators referred to the ‘struggle’ for civil rights while others later felt part of ‘student power’ or the ‘peace movement,’ and if they resisted the draft, the ‘resistance.’ . . . Movement, then, was an amorphous term that changed throughout the decade, . . . . Activists questioned the status quo . . . . Some activists did by action: . . . . Others did by the ‘great refusal,’ repudiating the values and morals of the older generation. Some shifted back and forth, but generally speaking those in the movement rejected what they considered was a flawed establishment. (preface) According to the Boomers, anyone who took a stand against their parents, the government, the war, or the system, whether they were hippies, student activists, women’s liberationists, or professors was part of their coalition. And to be considered an activist all a person had to do was yell at their parent for their values, partake in a sit in at a local college, or wear a tie dyed shirt, bell bottom pants, and a flower in their hair. Given that it was so easy to be part of “The Movement,” it is understandable that many musicians were also embraced as partners in their cause. There were a large number of musicians whose lyrics gave voice to the youth movement coalition. Two of the cherished groups that provided anthems that the Boomers took to heart were the Beatles and The Who, with their songs Revolution and My Generation. Both songs Miller 6 provided phrases that signified the mood of the Boomers and the movement as a whole. Though Revolution was written to ironically reflect the difficulty of change, the song was revered because it superficially spoke the goal of the movement. The first four lines said it all: “AAAAGGGHHHH!! / You say you want a revolution, / Well, you know. / We all want to change the world.” The Beatles recognized the daunting task of a world changing revolution, but their misinterpreted words undoubtedly bolstered the Boomers’ will to forge ahead. Similarly, The Who’s, My Generation, tapped in to the generational issues that frustrated the youth in the sixties. In his book, The Movement and the Sixties, Anderson recalls: “A subtle revolt was under way, a generational conflict in which many youth felt different from their parents . . . .The generation gap was becoming evident by 1965, and The Who expressed it in song:” People try to put us d-down, Just because we get around, Things they do look awful c-c-cold I hope I die before I get old. This is my generation . . . . Why don’t you all f-fade away . . . . I’m just talkin’ ‘bout my g-g-generation . . . . 6 In contrast to Revolution, the message of My Generation was meant literally. The lyrics “I hope I die before I get old” were intended to evoke resentment in all who heard them. For the Boomers and their parents alike, the words symbolized the growing tension and misunderstandings between the generations. Pointing out the discontent and disconnect between the two generations, My Generation proved to be especially significant for the Boomers. Seeming to support their angst, The Who’s words became a credence for the Boomers to live by. Already angered by their parents’ traditional values and morals, the Boomers took on an anti-authoritarian, anti-parents, and antiestablishment disposition. Thus the words “I hope I die before I get old” effortlessly evolved into Miller 7 the mantra “Don’t trust anyone over thirty.” Collectively, the goals of never trusting anyone over thirty, staying young forever, and changing the world for their generation, became one of the lasting legacies for both the Boomers and the 1960’s decade. However, while I speak of Boomer goals and legacies, it is important to note that not all Boomer’s took part in the movement. As the 1960’s ended, the oldest Baby Boomers were in their mid-twenties and beginning their adult years. Some had gone to college, graduated, and entered the workforce, while others had bypassed college to work or focus on the movement. Quoting Scott Turlow, Stephen Bennett and Stephen Craig explain: ’To recite the names of the various political hotbeds . . . .is to recognize that the cutting edge was traveled most often by the children of privilege. Generally speaking, blue-collar kids weren’t the ones out there chanting; they still wanted their piece of the American dream. (And they—and the poor—were, by and large, the kids doing the dying in Vietnam.). . .’ Thus, when all was said and done, a generation gap that seemed authentic to many—especially the media—turned out to be less important than the education gap that existed within the boomer cohort itself. (9-10) As pointed out by Bennett and Craig, many people held the false assumption that all Baby Boomers were involved in the movement. The inaccuracy of this assumption becomes clear with the knowledge that the Boomers involved in the movement were largely white, middle to upper class youth. While it is true that some, or maybe more accurately, many white, middle to upper class Baby Boomers took part in civil rights protests, anti-war marches, and the hippie counterculture, it is far from accurate to say that all people born between 1946-1964 were among them. Looking at the years alone that encompass the boom, one can clearly see the erroneousness of this assumption. According to the dates, the boom lasted a total of nineteen years, and began a mere fourteen years before 1960. Therefore, by the end of the 1960’s and the beginning of the 1970’s, only those Boomers born between 1946 and approximately 1955 were at Miller 8 least fifteen and old enough to really be a part of the movement. Obviously then, it is incorrect to think of all Baby Boomer’s in terms of the 60’s youth movement. But the assumption that all people born within a particular time period automatically share a uniquely definable and homogeneous identity is fast becoming one of America’s cultural, social, and generational legacies. Although this legacy was partly the result of the Baby Boom and the 60’s youth movement, it is a trend that helped spawn another equally false image of the youth group that came of age following the youngest boomers, Generation X. ~ ~ ~ In the 1990’s, the Boomer run mass media perpetuated the delusional legacy that all people born in a specific period of time share a unified identity. Recognizing that the largest cohort of youth to enter their twenties since the Boomers in the sixties were taking their place in the workforce, the media began focusing its attention on the group. Beginning in 1990, a barrage of print media articles labeling the cohort Generation X7, Baby Busters, Thirteeners8, Whiners, and Twentysomethings began to appear. Within these articles were explanations and accusations that purportedly defined the group as a whole but then spoke strictly about the newly minted white, middle to upper class “twentysomethings.” Additionally, while the authors called the group Generation X, Baby Busters, Whiners and Thirteeners, they often interchanged them with the label Twentysomethings. Ironically though, considering that Generation X was born between 1965 and 19769, in 1990, the oldest Xer’s were 25 and the youngest Boomers were 26. Therefore, just as it was inaccurate to assume that all members of the Baby Boom were part of the movement in the sixties, it was wrong for the media to refer to all twentysomethings as members of Generation X in the nineties. More interesting though, was that while the Boomer run media was speaking of the generation as a whole, they were focusing their attention on the Miller 9 ones they feared the most—the strangely familiar white, middle to upper class group whom they recognized as themselves. Confronted with a newly matured but strangely familiar youth group, the Boomers entered a state of alarm. Having experienced similar feelings thirty years prior, the Boomers relied on past coping strategies to deal with the perceived threat. In an attempt to control their anxiety and maintain their power, the Boomers shifted the angst they felt for their parents in the sixties to the youth they disliked in the nineties. Then, as many dominant and powerful groups have historically done, the Boomers aspired to make the youth group a new “other” by creating as large a distinction between the two as possible. Just as they had created a dualistic “we and they” generation gap in their youth, the Boomers endeavored to create a new generation gap in their adult years. The only difference was that instead of looking forward to their elders, they looked back to their successors. The first signs of aggression appeared in 1990 in the form of print media. To effectively construct the youth of the nineties as alien “others,” the Boomers needed to voice their concerns, express their opinions, and rally the support of their comrades. And what better way to do this than through the popular magazines that many white, middle to upper class people like themselves read and trusted. After all, it was through the media that the Boomer generation had been manipulated into believing that they were a powerful group. They had grown up both using and being used by the media, so it makes sense that the Boomers operating the media in the 1990’s would use it as their forum of discontent. The inundation began on July 16, 1990, with an article titled “Proceeding with caution: The twentysomething generation is balking at work, marriage and babyboomer values” (Gross and Scott). The attack lasted five years. Miller 10 The article “Proceeding with caution” set the tone, subject matter, and line of assault used by those that follow it. The issues to be raised in the article are cleverly placed in the alarming title and the pessimistic paragraph headings as a way to attract the attention of the Boomer (and older) target audiences. Fittingly, the captions read: “Family: The ties didn’t bind,” “Marriage: What’s the rush,” “Dating: Don’t stand so close,” “Careers: Not just yet, thanks,” “Education: No degree, no dollars,” “Wanderlust: Let’s get lost,” “Activism: Art of the possible,” “Leaders: Heroes are hard to find,” “Shopping: Less passion for prestige,” and “Culture: Few flavors of their own” (Gross and Scott). Finding this attention grabbing strategy successful, Business Week, Economist, Brandweek, Newsweek, and The New Republic followed suit. Some of their headlines read: “Move over boomers, the next generation of Americans –46 million people between 18 and 20—is coming on strong. Call it Generation X. It’s about to change our lives” (Zinn), “Oh grow up (Twentysomething generation)” (Economist), “Whiny Generation,” (Martin), and “Back from the future” (Kinsley). In the titles of each of these articles, the origins of distinction can be seen, but it was from within where the real assaults on Generation X occurred. In most of these print media articles, the authors began their attack on Generation X by making generalizations that denoted specific differences between the Boomers and X’ers. Some of the most alarming statements read: “They hate yuppies, hippies, and druggies . . . . This crowd is profoundly different from -- even contrary to -- the group that came of age in the 1960s . . . .” (Gross and Scott, par. 1, 3), “This is the generation of diminished expectations -- polar opposites of the baby boomers . . . .” (Zinn, 77), and “this group’s role models won’t be the yuppie types of the 1980s. (In fact, the 1980s yuppies are a target of ridicule)” (Langer, par. 21). Clearly, these generalities were used to create immediate alarm in those reading the articles. By making such Miller 11 distinct lines of division, the Boomers goals of making Generation X categorically strange “others” began to emerge. While the approaches of using catchy titles, subheadings, and generalities to grab the attention of readers was successful, the authors focused most of their attention on more specific categories of work, culture, and/or marriage as a way to fortify their efforts of making Generation X categorically strange “others.”10 The Boomers primary focus was on career and work habits because Generation X posed the largest threat to their job security. Criticizing the group, the Boomer’s main contention was that Generation X whined too much about the lack of, and type of jobs available to them. In an article titled “The Whiny Generation,” David Martin suggested that the X’ers limited job prospects resided within themselves. This was evident when Martin stated: The Whiners’ most common complaint is that they’ve been relegated to what Mr. Coupland calls McJobs—low-paying, low-end positions in the service industry . . . . But whose fault is that? Here’s a generation that had enormous educational opportunities. But many Whiners squandered those chances figuring that a good job was a right not a privilege. . . .They had a chance to reach higher but often chose not to or chose foolishly or unwisely . . . . Those who thought that fine arts or film studies would yield more than a subsistence living were only fooling themselves. (10) Martins’ statement had two objectives. The first was to place blame on Generation X for a lack of quality job opportunities. Rather than acknowledging that Generation X “entered what was, for newly minted college grads, arguably the worst job market since World War II” Martin suggested that many X’ers were too irresponsible to even attend college (Giles, par. 8). Martin’s second objective was less visible but still apparent when he noted that those who attended college “chose foolishly or unwisely.” Making such a statement, Martin’s goal was clearly to show the differences between people like him who chose legitimate careers in law and politics, and people like “them” who chose fields in Liberal Studies. Doing so, Martin suggested that Miller 12 Generation X was less qualified, less intelligent, and less important than the successful and smarter Baby Boomers like himself. Thus, Martin created a faulty discourse that suggested Generation X was profoundly different, and therefore strange in comparison to its predecessors. Refusing to change the subject, the media continued to criticize Generation X by changing its focus from career complaints and choices to career habits and motives. Another equally demoralizing discussion occurred when the Boomers accused Generation X of having unreasonable, uncalled-for, and completely different work habits and motives than the Boomer elite. In Time a section titled “Careers: Not just yet,” the authors began their attack by criticizing Generation X’s work habits. Gross and Scott stated: “Companies are discovering that to win the best talent, they must cater to a young work force that is considered overly sensitive at best and lazy at worst” (par. 18). In this quote, the authors made it clear that the X’ers entering the Boomer’s workplace were difficult to work with. They also suggested that the younger group was thin-skinned, pathetic, lazy, and unrealistically expecting opportunities to be handed to them on a silver platter. To support this stance, the authors turned to praising the Boomers and faulting Generation X by emphasizing what they perceived to be negative attributes of character. The authors did this by pointing out: “In contrast to baby boomers, who disdain evaluations as somehow undemocratic, people in their 20s crave grades, performance evaluations and reviews. They want qualifications for their achievement” (par 19). In a weak attempt to confirm this negative claim, the Boomer authors provided quotes from two successful and other highly positioned Baby Boomers. The first quote by a senior vice president named Penny Erikson read, “’Unlike yuppies, younger people are not driven from within, they need reinforcement . . . .They prefer short-term tasks with observable results’” (par. 19). Similarly unjust, the second quote from Marian Salzman, an editor at large read, “’The difference between Miller 13 now and then was that we had a higher threshold for unhappiness . . . .I always expected that a job would be 80% misery and 20% glory, but this generation refuses to pay its dues’” (par 22). In each of these statements, Generation X was portrayed, in comparison to the Boomers, as being largely deficient in work motive, habit, and character. Attempting to demoralize Generation X is such a manner the Boomers underscore their own appearance as reasonable, motivated, and moral members of corporate America. The object of making such distinctions between the Boomers and the X’ers, and then supporting them with quotes by Boomer’s who are in positions of authority, the authors’ and thus Boomers’ suggest that they possess a far superior moral fortitude than the X’ers. Also, by depicting Generation X as insecure youngsters who have short attention spans and require constant praise by Boomers, the authors excessively strengthen the Boomer image and credibility while completely discrediting and demoralizing the Xer’s. Evaluating the tactics used by the Boomers to differentiate between both groups, the Boomers revealed that they were fearful of Generation X. With Generation X entering an already Boomer saturated job market, the older group risked losing their jobs to the newest and most talented recruits. Having grown up in a world of technology, X’ers may have been years ahead in their knowledge of computers than their predecessors, and having just completed college, they were bound to have a better understanding of the most up to date technologies. Additionally, due to their age and inexperience, the X’ers cost less than the older and more experienced Boomers to employ. Thus at a time of massive corporate downsizing, the Boomers were understandably fearful of losing their jobs to the newest crop of graduates, and consequently their money, and comfortable middle to upper class lifestyle. As a way to deal with this fear, the Boomers attempted to make the youthful X’ers out to be troublesome complainers whom employers would not want to hire. In doing so, the Boomers revealed not only that they were fearful of losing their Miller 14 jobs, money and status to Generation X, but that they Boomers were self-absorbed and selfish people who were more concerned with themselves than seeing the younger group succeed in life. Unfortunately though, the Boomer’s desire to bolster their own image by pointing out Generation X’s faults and inadequacies did not stop with career complaints and differences; they continued their assault by accusing the younger group of living in the past and being too brainless to create anything remotely original. The absolutely insidious belief that Generation X was brainless and uncreative first appeared in Time’s article “Proceeding with caution.” In the last section called “Culture: Few flavors of their own,” the authors humorously provided some insight into the minds of the youth when they stated: Down deep, what frustrates today’s young people – and those who observe them – is their failure to create an original youth culture. . . . Why hasn’t the twentysomething generation picked up the creative gauntlet? One reason is that the generation believes the artistic climate that existed when the Beatles and the Who were writing is no longer viable. (Gross and Scott, par. 35, 37) Seeming to support its predecessor, Business Week made similar comments. They read, “Busters are also creating their own pop culture by borrowing discarded boomer icons [such as reruns of Gilligan’s Island and the Brady Bunch] and mocking them while making them their own . . . . Busters’ passion for Boomer castoffs is also creeping into fashion. This fall the ‘70’sinspired ‘grunge’ look has influenced some . . .younger designers” (Zinn, 77). Michael Kinsley, writing for The New Republic, condemned the ignorant Xer’s for fashioning their youth sentiments out of those of the past when he said, “Start with originality. C’mon you guys. Generational self-pity and existential despair, which [you] Xer’s are marketing as [your] own, are hardly new” (par 12). What I refer to as humorous in these statements may more accurately be considered selfabsorption on the part of the Boomers who wrote them. To accuse a younger group of imitating Miller 15 their elder's music, fashion, and cries of despair, on top of accusing them of being frustrated about their own inability to create something original, reflects a complete shallowness by the elders doing the accusing. If the Boomers’ goal was to make the X’ers look so bad that the Boomer community would consider them “others,” these insults were bound to do the trick. Not only did these diatribes make the X’ers out to be psuedo-youth, unable to do more than blandly reproduce the youth culture they stole from their predecessors, they made the Boomers out to be God-like people who could never be out-smarted or out-created. Ironically though, the Boomers were so caught up in shallow arrogance, that they failed to realize that the X’ers were not pining for the past, rather they were manipulating the previously Boomer dominated markets of music and clothing (e.g. Grunge) into their own. Accordingly, when the Boomer authors accused Generation X of being incapable of creating an original thought (or music, or clothing), as well as idolizing everything from the Boomers’ past, they created and perpetuated the myth that their youth culture was original, and thus far superior to that of the Xer’s. Consequently, the Boomers bolstered their own image as well as their egos, by stifling the notion that the Generation X youth culture could ever outdo that of the Boomers. The Boomers second approach of accusing Generation X of having no originality was just as revealing as their first. While the Boomers showed themselves fearful, self-absorbed, and selfish by criticizing the Xer’s work habits, motives, and character, they showed their frustration with growing old in the second. By suggesting that the X’ers idolized the Boomers’ music, clothing, and television programs, they revealed that they themselves were incapable of leaving the past behind and accepting the present or future. Additionally, by refusing to recognize that fashion, music, and youth culture had experienced changes in the last thirty years, and that those changes had little to nothing to do with the Boomer generation, the group revealed that they lived Miller 16 in a state of denial. Remembering that the Boomers’ departed the sixties chanting “I hope I die before I get old” and “Never trust anyone over thirty,” it makes sense that the Boomers, now in their forties and fifties, were frustrated with the fact that they were now over thirty. Logically then, because the Boomers “hadn’t died before they got old,” and were now “elders” rather than youth, it did them no good to maintain the notion that youth are superior to adults. Rather, to preserve their status as the pre-eminent group in society, the Boomers had to destroy the old myth of youth supremacy and construct a new one premised on the assumption that “everything Boomer” is legitimate and everything “other” is not. In attempting to convince the public that the Boomer music, fashion, and youth culture was superior, they revealed that they live in a bubble that is lined with the myth that “everything Boomer” is original and superior. So to bolster their image and destroy everything “other,” the Boomers falsely announced that the younger X’ers had produced nothing original, and reduced anything they had produced to stolen replicas of the past. Having then created distinct divisions between the Boomers and the Xer’s in the categories of work and culture, the Boomers moved in for the kill. To successfully portray Generation X as the “other,” they went (metaphorically speaking) straight for the heart and falsely created the belief that X’ers were refusing to get married and maintain what the Boomers considered, an “acceptable” lifestyle. While a few articles directly accused Generation X of refusing to get married, the topic was often hidden within discussions of dating and living accommodations. Most damaging though, were the statements that did not hide behind those pretenses. Statements such as, “The generation is afraid of relationships in general, and they are the ultimate skeptics when it comes to marriage” falsely perpetuate the belief that the group refused to get married (Gross and Scott, par. 14). Similarly damaging was a statement found in the same magazine. It read, “Despite Miller 17 their nostalgia for family values, few in their 20’s are eager to revive a 1950’s mentality about pairing off” (Gross and Scott, par.16). Strategically, not only did this statement suggest that Xer’s were not willing to commit to long term relationships, it recapped the notion that they were longing for the past. Ironically though, the authors were criticizing the group for refusing the same 1950’s bourgeois lifestyle that the Boomers had so noisily rejected thirty years prior. The Boomer authors appeared to have forgotten that members of their generation were the ones who originally delayed marriage and family as a way to reject entering the bourgeois lifestyle they fought against in their movement. Through their hypocrisy though, the Boomers succeeded in stereotyping Generation X as a group who refused to get married, start families, and accept their place in middle to upper class society. In doing so, the Boomers finalized their argument that Generation X was such a strange and atypical group, that for the protection of all they fought for in the sixties, the group must be viewed as threatening “others.” Recognizing a part of themselves in Generation X, the Boomer media made the final attack in their generational war by criticizing the group for postponing or refusing marriage and family. Thirty years before, the Boomers put off getting married as a way to refuse their parents’ lifestyle, and when they recognized this trend in the X’ers, it scared them. For if the X’ers were really like the Boomers, they too could revolt and refuse the dominant (Boomer) ideology, and if this was to happen, then the Boomers risked losing all that they thought they had changed. Additionally, if the Boomers had successfully changed the system that they fought against in the sixties, then why in the world would the X’ers want to change it again? Allowing the X’ers the chance to rise as a force and answer this question was not a risk they were willing to take. So as other dominant groups have done in the past, the Boomers wanted the X’ers to look so bad that no one, including the X’ers, would respect or want to associate with them. Therefore, the Miller 18 Boomers constructed negative and appalling images and stereotypes to prevent Generation X from uniting and revolting against the older and dominant group. Ultimately, by bashing Generation X as they had bashed their parents’ generation before, the Boomers hoped to maintain their powerful status as dominant elite, and insulate themselves from the facts that they had grown old, failed to change the system they refused in their youth, and may not have revolutionized the world for the better. Analyzing early 1990’s media in the year 2000, I have the luxury of knowing that the Boomers did not succeed in making Generation X the “other.” While they used valid information to make their case, the Boomer’s failure was a result of their inaccuracies when evaluating it. The Boomers were correct to recognize that Generation X did not like the demands of corporate America, but it is incorrect to say that their animosity towards it was invalid. Generation X grew up witnessing the results of long work hours; many experienced absent parents, were latchkey kids, and “were deliberately encouraged to react to life as you would hack through a jungle: keep your eyes open, expect the worst, and handle it on your own” (Strauss and Howe, 329). Similarly, the Boomers were right when they recognized that Generation X was borrowing songs and fashion from their youth culture, but they were wrong to assume that it was because the X’ers were unoriginal. Preoccupation with supremacy prevented the Boomers from realizing that the X’ers grew up listening to the Beatles and The Who, watching Gilligan’s Island and the Brady Bunch, and experiencing the Movement and Woodstock in movies and on television. Accordingly, when the X’ers rekindled some of the Boomer’s youth culture, it was not due to idolization, it was due to familiarity. Finally, the Boomers were accurate to recognize that the X’ers were postponing marriage and family, but they were inaccurate to assume it was because they were refusing the dominant lifestyle. As Jeff Giles notes, “Generation X’s Miller 19 childhood coincided with divorce’s big bang: in the ‘70’s and ’80s, divorce touched 1 million children a year . . . . When their parents divorced, many children felt the bottom fall out from under them financially . . . .[and] emotionally too” (par 14). Many X’ers who experienced divorce saw their uneducated mothers struggle to make ends meet, and accordingly learned the importance of education at an early age. It is thus reasonable to assume that the X’ers were only postponing marriage until they completed their education, were financially secure, and mature enough to handle the responsibilities of marriage and family. From the vantage point of 2000, it is easy to see why the Boomer controlled media attempted to make Generation X the “other.” Having read both sides of the argument, I realize that there are more similarities between the Boomers and the X’ers than there are differences. It is also clear that the Boomers recognized these similarities early on and it scared them. In their eyes, the group they called Generation X, Twentysomething, Thirteeners, and Whiners came from the same race and class, but looked (because of their clothes and hair) and acted differently than they had in their youth. This “uncanny” recognition (familiar yet strange), created an anxiety in the Boomer’s that they had not felt in thirty years. Relying on the same “we and they” strategy they had used against their parents, the Boomers portrayed Generation X as different “others” as a way to take control of the situation, maintain the powerful status they were accustomed to, deny the similarities, and ease their anxiety. Fortunately, the Boomer’s motives did not affect society’s perception of the group, nor did it succeed in subjugating them. A few years after the Boomers began their forum of discontent, many articles and books were written in support of Generation X. Some were written in defense, some pointed out the similarities between the two, and others criticized the Boomer’s for being hypocritical and Miller 20 misrepresenting the group. One of my favorite quotes comes from Alexander Star in an article titled “The Twentysomething Myth”: How can one generalize about a group that is said to be politically disengaged and politically correct, obsessed with surfaces and addicted to irony, scarred by Watergate and Vietnam and unaware of them, technologically savvy and unconditionally ignorant, busy saving the planet and craving electricity and noise, prematurely careerist and proud to be lazy, unwilling to grow up and too grown up already? (par 17). I am fond of this quote because it addresses many of the erroneousness assumptions the media used to depict Generation X in the early nineties. Written by an Xer, it also shows that the group did not buy the Boomers attempt to discredit, demoralize, and disband them, rather, the opposite occurred. Generation X has proven itself strong, intelligent, motivated, hard working, successful, happily married, and non-resentful. Learning resilience at an early age, many X’ers figured out not only how to adjust to adversity, but how to overcome it. Thanks to this, the X’ers did not crawl into a hole and hide when the battle began, nor did they fall into a pattern of self-pity; they stood tall, took the beating, and came out stronger because of it. Miller 21 NOTES 1 In her book Marketing to Generation X, Karen Ritchie explains: “Using birth years 1943- 1960, the number of Boomers alive in 1995 is approximately 69.5 million—a huge number, but significantly smaller than the 75 million Boomer noses counted in earlier texts using the birth years 1946-1964. . . .Using birth years 1961-1981, Generation X accounted, in 1995, for 79.4 million people. That is correct—there are more Xers than Boomers, and there have been since about 1980. . . .[The Boomers] can no longer claim to be the largest generation ever produced in America” (16). See chart on page17 for the Total Population, Xers vs Boomers, years 19702010. 2 David M. Gross and Sophronia Scott, Proceeding With Caution: The Twentysomething Generation is Balking at Work, Marriage, and Babyboomer Values,” Time (1990): par 23. 3 In Constituting Americans: Cultural Anxiety and Narrative Form, Priscilla Wald explains Frued’s theory of “The Uncanny” based on his 1919 essay “The Uncanny.” 4 Susan Mitchell, The Official Guide to the Generations: Who They Are. How They Live. What They Think (Ithaca: New Strategies, 1995) xxi. Following the end of World War II and the return of soldiers in 1945, America experienced an increase in birth rates. The increase resulted in what is commonly known as the Baby Boom. According to Mitchell and most primary source print media articles, the Baby Boomers were born between 1946 and 1964. In contrast, secondary sources written by William Strauss, Neil Howe, Karen Ritchie state that the Baby Boomers were born between 1946 and 1960. 5 William Perry, Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years; A Scheme [by] William G. Perry, Jr. (New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1970). Information Miller 22 was obtained on a handout from Diane Gillespie in BLS 435: Interactive Learning Theory, Winter 2000. 6 Anderson 93. Song lyrics have been modified from what Anderson provided in his book. Song in its entirety can be found on the World Wide Web at http://lenny.dyadel.net/lyrics.htm. 7 The label “Generation X” is thought to have been constructed by Douglas Coupland, author of the novel Generation X: Tales For an Accelerated Youth. 8 The label “Thirteener” was first used by William Strauss and Neil Howe in their collaborative book titled Generations. 9 Again, these are discrepancies between the years that members of Generation X were born. Susan Mitchell as well as a majority of primary sources state that Xers were born between 1965 and 1976. Conversely, Strauss, Howe, and Ritchie state they were born between 1964 and 1981. 10 To adequately understand the methods used to construct Generation X as the “other,” it is necessary to examine the categories of work, culture and marriage separately, yet through the lenses of only the most powerful and convincing arguments. Many of the articles cited in this paper use the same arguments to support the same cases. To prevent repetition, I will cite only the strongest evidence. Work Cited Anderson, Terry H. The Movement and The Sixties. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. Bhaba, Homi K. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994. Beatles. “Revolution.” John Lennon and Paul McCartney, 1968. The Unofficial Beatles Lyrics Archive. http://user.tninet.se/~qzd510w/b-beatles%201968.htm. Miller 23 Coupland, Douglas. Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. New York: St. Martin’s, 1991. Craig, Stephen C., and Stephen Earl Bennett, eds. After the Boom: The Politics of Generation X. Lanham: Rowman, 1997. Douglas, Susan J. Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female With the Mass Media. New York: Times Books, 1994. Giles, Jeff. “Generalizations X.” Newsweek. 6 June 1994: 37 pars. Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe. http://web.lexis-nexis.com/universe/docu… . 7 Jan. 2000. Gross, David M., and Sophronia Scott. “Proceeding With Caution: The Twentysomething Generation is Balking at Work, Marriage, and Babyboomer Values.” Time. 16 July 1990: 49 pars. Expanded Academic ASAP. http://web2.infotrac.galegroup.com. Article A9161161. 14 Nov. 1999. Kinsley, Michael. “”Back From the Future.” The New Republic. 21 March 1994: 15 pars. Expanded Academic ASAP. http://web5infotrac.galegroup.com. Article A14909246. 2 Feb. 2000. Langer, Judith. “Twentysomethings: They’re Angry, Frustrated and They Like Their Parents.” Brandweek. 22 Feb. 1993: 24 pars. Expanded Academic ASAP. http://web2.infotrac.galegroup.com. Article A13518934. 14 Nov. 1999. Martin, David. “The Whiny Generation.” Newsweek 1 Nov. 1993: 10. Mitchell, Susan. The Official Guide to the Generations: Who They Are. How They Live. What They Think. Ithaca: New Strategies 1995. “Oh Grow Up. (Twentysomething Generation) (American Survey).” Economist (US). 26 Dec. Miller 24 1992: 9 pars. Expanded Academic ASAP. http://web2.infotrac.galegroup.com. Article A13282242. 14 Nov. 1999. Perry, William. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years; A Scheme [by] William G. Perry, Jr. New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston 1970. Ritchie, Karen. Marketing to Generation X. New York: Lexington 1995. Star, Alexander. “The Twentysomething Myth.” New Republic. 4 Jan. 1993: 18 pars. Expanded Academic ASAP. http://web2.infotrac.galegroup.com. Article A13262478. 14 Nov. 1999. Strauss, William and Neil Howe. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow, 1991. Wald, Priscilla. Constituting Americans: Cultural Anxiety and Narrative Form. Durham: Duke UP, 1995. Who, The. “My Generation” Brunswick, 1965. Always on the Run. http://lenny.dyadel.net/lyrics.htm. Zinn, Laura. “Move Over, Boomers: The Busters are Here—and They’re Angry.” Business Week 14, Dec.1992: 74-79+.