Report from the

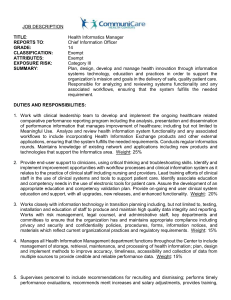

advertisement