WIPO/GRTKF/IC/19/12

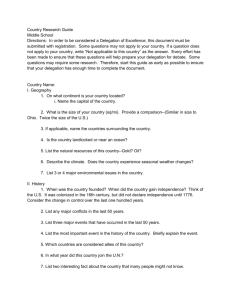

advertisement