Counseling for Wellness and Justice:

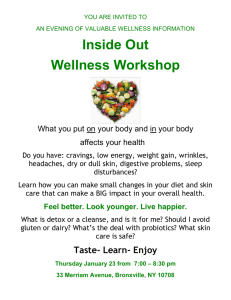

advertisement