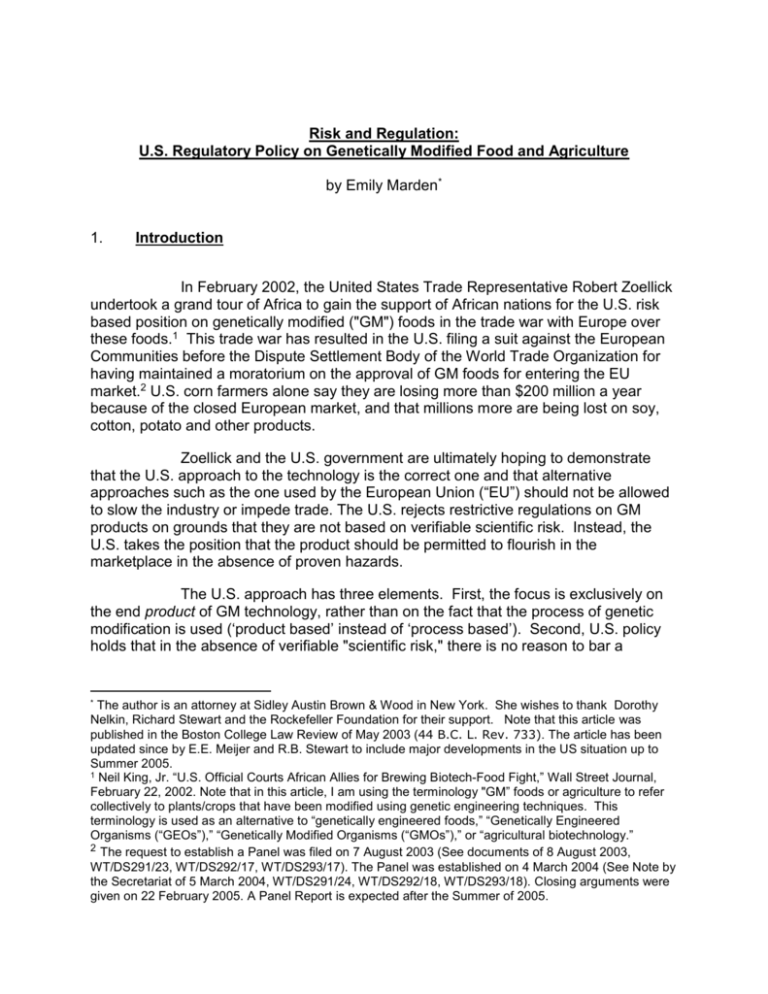

1. Introduction - NYU School of Law

advertisement