Military presses to exempt millions of acres from environmental laws

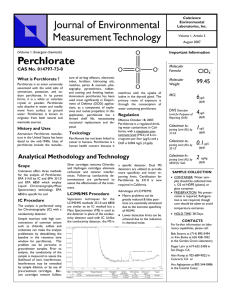

advertisement

Military presses to exempt millions of acres from environmental laws Both sides armed with science and studies in conflict over health risks Written by Peter Eisler Written by Peter Eisler CAMP EDWARDS, Mass. -- When soldiers from the Army National Guard show up here for artillery training, they fire their howitzers indoors -- on simulators. ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, Md. -- Each day, a bit more perchlorate from beneath this vast Army installation leaches into the well fields that give the city of Aberdeen its drinking water. The EPA ordered a halt to live artillery training at Edwards in 1997 because munitions chemicals were leaching toward the aquifer that provides drinking water for all of Cape Cod -- more than 500,000 people in summer. Perchlorate is a pollutant from munitions used for decades at the 75,000-acre weapons-testing facility. In the past two years, the chemical has shown up in all 11 of Aberdeen's city wells. Now the restrictions here are the Pentagon's Exhibit A in a controversial campaign for legislation that would exempt more than 20 million acres of military land from key facets of the Clean Air Act and the two federal laws governing hazardous-waste disposal and cleanup. The top environmental officials of nearly every state oppose the legislation, as do 39 state attorneys general. And the Bush administration's own environmental officials have tried to limit the exemptions plan. In a memo to White House officials last year on a draft of the legislation, the EPA complained that some provisions "could interfere with the ability of states to enforce air pollution and drinking water (rules) that protect public health." The memo, obtained by USA TODAY, urged revisions so regulators could "address imminent and substantial endangerment" from military pollution. The White House refused, and the EPA had no choice but to endorse the legislation. The Pentagon began its push for exemptions from environmental and conservation laws in 2002. Only by blending water from the most contaminated wells with flows from those with just trace levels has the city kept perchlorate concentrations in "finished" drinking water below 1 part per billion (ppb). That's the point at which the state warns of health risks. The city of 13,500 people also buys 500,000 gallons of clean water a day from the county. Now city officials say they need to spend $250,000 to install filter systems on the most tainted wells. But the Pentagon refuses to clean up perchlorate at Aberdeen and dozens of other sites nationwide. It's part of a battle with the EPA over how much of the chemical can safely be left in soil and water. The dispute highlights a Defense Department push to take regulatory fights into the laboratory. State and federal environmental agencies are using new scientific studies to make a case for tighter limits on military pollutants, which would add billions to Pentagon cleanup costs. At the same time, the armed services are enlisting their own scientists and funding research to challenge those studies. Since then, Congress has granted exemptions from five laws. For example, the armed services got leeway to train on military land that provides wildlife habitat protected by the Endangered Species Act. They also were freed to conduct sea exercises using equipment that might harm animals covered by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. The big battles involve perchlorate and trichloroethylene, or TCE, a solvent used in military vehicle maintenance. The EPA's latest studies say health risks from exposure to both chemicals are higher than previously believed. After the Pentagon complained to the White House about the studies, the EPA decided that its research, already checked by independent panels, should go to the National Academy of Sciences for more study. Three remaining exemption requests govern Alex Beehler, assistant deputy undersecretary of hazardous-waste disposal, hazardous-waste cleanups and air pollution. So far, Congress has balked at the remaining waiver requests. But Republican leaders say they are committed to passing them. And the Pentagon still is pushing hard -- with White House support. "There are immediate and unquestionable (military) readiness risks associated with how these three environmental statutes are being interpreted," says Paul Mayberry, deputy undersecretary of Defense for readiness. Yet regulators have never used the laws to limit military activities. Even the restrictions at Edwards, while cited by the Pentagon, were ordered under a drinking-water statute not covered by the waiver proposal. Last year, then-EPA administrator Christie Whitman complained to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld that Pentagon officials were misleading Congress in hearings on the exemptions legislation. In a letter to Rumsfeld, obtained by USA TODAY, Whitman said she was "very concerned" that Defense officials were creating an "erroneous impression . . . that EPA has prevented vital military training." The three remaining requests for exemptions would reduce state and federal regulators' long-held power to force the military to deal with pollution on "operational" land -- unless the contamination already had spread off site. That's too late, regulators say, to protect neighbors from health risks. Pentagon officials say the exemptions are needed to ensure that regulators don't use hazardous-waste rules to demand cleanups on training ranges littered with used ordnance, which can leach chemicals such as TNT into soil and water. They also fear that clean-air rules could be used to block the transfer of aircraft to bases where air pollution from power plants and other sources already exceeds the Clean Air Act's emissions limits. Defense for environment, says the military wants to be "a responsible player" in regulatory debates. Diving into the science, he says, "is one small but appropriate way we can do so." Environmental groups disagree. The Pentagon "is using the White House to come from the top," says Lenny Siegel of the Center for Public Environmental Oversight in California. "Rather than having the same standing as states, communities, industry groups or anyone else, they're above everybody." The EPA has not complied with Freedom of Information Act requests filed by USA TODAY seeking copies of its communications with the White House and Pentagon. EPA research chief Paul Gilman says the agency was not forced to go to the National Academy of Sciences. "In both instances," he says, "it was our idea." No one owns more properties contaminated with perchlorate and TCE than the Pentagon, federal records show. And the military is leading the charge against efforts to clamp down on the pollutants: * Perchlorate. The EPA's disputed risk study finds that small doses raise risks of thyroid problems and related ills in fetuses and infants. The study suggests that 1 ppb of perchlorate in drinking water -- the equivalent of a half-teaspoon in an Olympic-size swimming pool -- is a safe limit for pregnant women and children. The armed services have argued that levels up to 200 ppb are safe. Col. Daniel Rogers, an Air Force environmental lawyer, told the National Academy last year that the EPA's study is "biased . . . and scientifically imbalanced" because it ignores other research that has found no proof of ill effects among people exposed to perchlorate. Even if environmental agencies continue to defer to military needs, Defense officials say, activists could sue to force regulatory action. The academy review means the EPA probably won't set pollution limits on perchlorate before late 2006, officials say. Meanwhile, some states are considering their own limits of under 10 ppb in drinking water. Regulators have a different concern: The military * TCE. The EPA's new risk study suggests a need could use the exemptions to duck legitimate environmental orders. Regulators also note that the president already can exempt military sites from the laws at issue. Last year, Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz directed the armed services to "give greater consideration to requesting such exemptions" to the laws if they hinder training. But no requests have been submitted. Meanwhile, the military still cites the live-fire restrictions at Camp Edwards as proof that it needs relief from the clean-air and hazardous-waste laws. As far back as 2001, Maj. Gen. Robert Van Antwerp, then an Army assistant chief of staff, told Congress that the Army was "very concerned" about the Edwards precedent. "If applied to a major training installation" he said, "the results could be catastrophic." But officers at Edwards say they have adapted to the restrictions, using the howitzer simulators and sending troops to other bases a few times a year for live fire exercises. "I wouldn't say training has been curtailed," Capt. Winfield Danielson says. "Most of the training the units did before, they can still do." GRAPHIC: PHOTOS, B/W, Sean Dougherty for USA TODAY (2); GRAPHIC, B/W, Karl Gelles, USA TODAY, Source: Air Force Center for Environmental Excellence (ILLUSTRATION); GRAPHIC, B/W, Karl Gelles, USA TODAY (MAP); On Cape Cod: Spc. Andrew Hawthorne demonstrates loading an artillery piece at Camp Edwards in Massachusetts. Live-fire training was halted there in 1997; now simulators are used. <>Filtering: A soil-cleaning operation is underway at Camp Edwards, where pollution from live munitions endangered drinking water.<>How pollution can enter the water supply (graphic) for tighter limits on contamination. It concludes that TCE vapors from contaminated soil and groundwater can seep into buildings and boost cancer risks. The EPA's independent Science Advisory Board checked the study and "was largely supportive of the approach and conclusions," says review leader Henry Anderson, chief medical officer for Wisconsin's Division of Public Health. But the Pentagon says the study is "based on the ardor and hypotheses of the EPA authors, rather than sound scientific evidence." Some states already are tightening their TCE regulations, but the EPA is waiting to adjust federal rules until the academy finishes its review -- in 2007. The groundwater feeding Aberdeen's well fields has perchlorate levels up to 24 ppb, but officials at the proving ground are bound by the Pentagon's freeze on cleanups. "Generally, we'd be doing something to address it at this point, with it showing up in the wells," says Ken Stachiw, the base's environmental restoration chief. The EPA could order a cleanup if the perchlorate posed a "substantial hazard" to drinking water. But the agency has resisted staff suggestions to do so because perchlorate levels in Aberdeen's "finished" water haven't exceeded 1 ppb. "Nobody is standing up for the community," says Glenda Bowling, a local activist. "We could wake up one day and it could be 20 parts per billion in that water, and we wouldn't be able to drink it." GRAPHIC: PHOTO, B/W, James Kegley for USA TODAY; GRAPHIC, B/W, USA TODAY (MAP); Chemicals turning up in wells: Ken Stachiw, environmental restoration chief at Aberdeen Proving Groundin Maryland, checks a map of well sites. Behind him, engineers Gordy Porter and Naren Desai run tests.