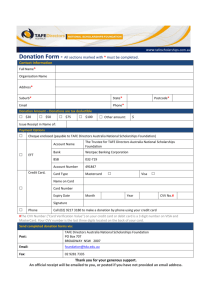

- National Centre for Vocational Education Research

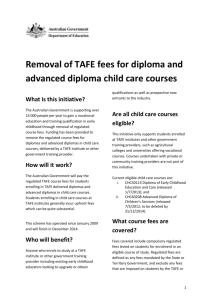

advertisement