Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive

advertisement

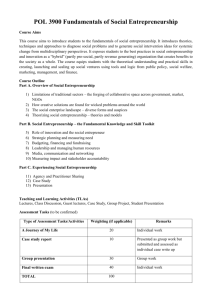

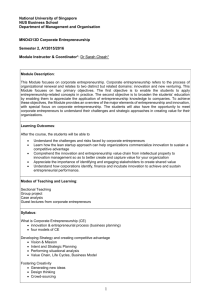

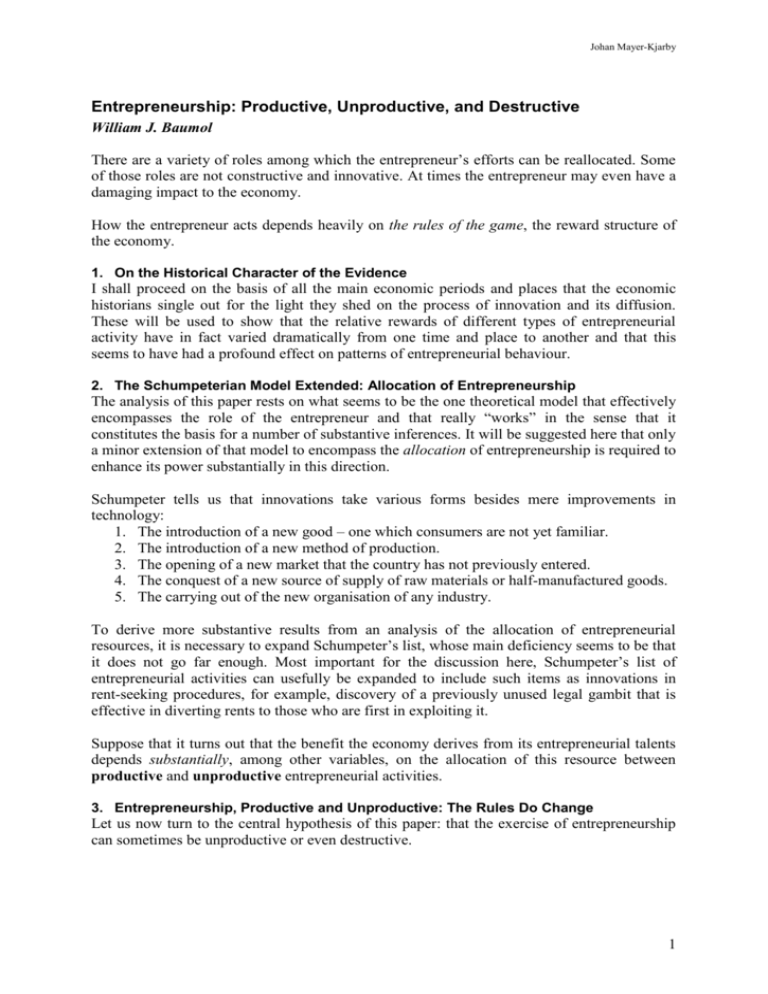

Johan Mayer-Kjarby Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive William J. Baumol There are a variety of roles among which the entrepreneur’s efforts can be reallocated. Some of those roles are not constructive and innovative. At times the entrepreneur may even have a damaging impact to the economy. How the entrepreneur acts depends heavily on the rules of the game, the reward structure of the economy. 1. On the Historical Character of the Evidence I shall proceed on the basis of all the main economic periods and places that the economic historians single out for the light they shed on the process of innovation and its diffusion. These will be used to show that the relative rewards of different types of entrepreneurial activity have in fact varied dramatically from one time and place to another and that this seems to have had a profound effect on patterns of entrepreneurial behaviour. 2. The Schumpeterian Model Extended: Allocation of Entrepreneurship The analysis of this paper rests on what seems to be the one theoretical model that effectively encompasses the role of the entrepreneur and that really “works” in the sense that it constitutes the basis for a number of substantive inferences. It will be suggested here that only a minor extension of that model to encompass the allocation of entrepreneurship is required to enhance its power substantially in this direction. Schumpeter tells us that innovations take various forms besides mere improvements in technology: 1. The introduction of a new good – one which consumers are not yet familiar. 2. The introduction of a new method of production. 3. The opening of a new market that the country has not previously entered. 4. The conquest of a new source of supply of raw materials or half-manufactured goods. 5. The carrying out of the new organisation of any industry. To derive more substantive results from an analysis of the allocation of entrepreneurial resources, it is necessary to expand Schumpeter’s list, whose main deficiency seems to be that it does not go far enough. Most important for the discussion here, Schumpeter’s list of entrepreneurial activities can usefully be expanded to include such items as innovations in rent-seeking procedures, for example, discovery of a previously unused legal gambit that is effective in diverting rents to those who are first in exploiting it. Suppose that it turns out that the benefit the economy derives from its entrepreneurial talents depends substantially, among other variables, on the allocation of this resource between productive and unproductive entrepreneurial activities. 3. Entrepreneurship, Productive and Unproductive: The Rules Do Change Let us now turn to the central hypothesis of this paper: that the exercise of entrepreneurship can sometimes be unproductive or even destructive. 1 Johan Mayer-Kjarby Proposition 1: The rules of the game changes dramatically from one period to the next. Proposition 2: The entrepreneurs behaviour changes in a manner that corresponds to the rules of the game. Ancient Rome In ancient Rome they had no reservation about the desirability of wealth or about its pursuit as long as it did not involve participation in industry or commerce. Persons of honourable status had three primary and acceptable sources of income: landholding, ”usury” (lending money for a fee) and “political payments” (taxes and other payments). Personal political payments in Rome are misunderstood when labelled “corruption”. We are here faced with something structural in the Roman society. Commerce and industry was mainly undertaken by freedmen, former slaves that bore a stigma for life and hence needn’t mind the loss in prestige by their trade. In other words, the rues of the game seem to have been heavily biased against the acquisition of wealth and position through Schumpterian behaviour. (see above) The bottom line is that the Roman reward system, although it offered wealth to those who engaged in commerce and industry, offset this gain through the attendant loss in prestige. Medieval China 1. In China the monarch commonly claimed possession of all property in his territories. Confiscation of private property was entirely in order. This led to those who had resources to avoid investing them in visible capital. This was a substantial obstacle to economic expansion. 2. In addition, China reserved its most substantial rewards in wealth and prestige for those who climbed the ladder of imperial examinations. Wealth was in prospect for those who passed the examinations and appointed to government positions. But the sources of earnings was not the salaries, which where meagre, but corruptive income in the form of payments from the people. 3. Enterprise was not only frowned on but may have been subject to obstructions imposed by the officials. Enterprises were stopped and successful enterprises were taken over and nationalised. The earlier middle ages Before the rise of the cities and before monarchs were able to subdue the aggressive activities of the nobility, wealth and power were pursued primarily through military activity. It seems reasonable to interpret the warring of the barons in good part as the pursuit of prestige but also of an economic objective. (In England, with its institution of primogeniture younger sons who chose not to enter clergy ha no socially acceptable choice other than warfare to make their fortunes.) This violent economic activity inspired frequent innovations within the military sector. 2 Johan Mayer-Kjarby The later middle ages By the end of the eleventh century the rules of the game had changed from those of the Dark Ages. A number of activities that where neither agricultural nor military began to yield handsome returns. Architect-engineers could live in great luxury. But, a far more common source of earnings was the water driven mills in France and southern England. Also the monks had an important economic role as enthusiastic entrepreneurs. The rules of the game appeared to have offered substantial economic rewards to the exercise of Cistercian entrepreneurship. The order received support from the laity and in the form of exemptions from road and river tolls. Fourteenth Century The fourteenth century brought with it an increase in military activity. Payoffs, surely must have tilted to favour more than before inventions designed for military purposes. Clearly, the rules of the game had changed to the disadvantage of productive entrepreneurship. Early Rent Seeking Enterprising use of the legal system for rent-seeking purposes has a long history. For example 12th century mill owners won prohibition of use of animal driven mills. In the middle ages rent seeking also gradually replaced military activity as a prime source of wealth and power. Rent seeking entrepreneurship took many forms such as the quest for grants of land and patents of monopoly from the monarch. To illustrate this the noble families earned probably 10 times more than the richest merchants. The central point of all the preceding discussion seems clear. If entrepreneurship is the imaginative pursuit of position then we can expect changes in the structure to modify the nature of the entrepreneur’s activities. 4. Does the allocation of entrepreneurship matter much? Proposition 3: The allocation of entrepreneurship between productive and unproductive activities can have a profound effect on the innovativeness of the economy and the degree of dissemination of its technological discoveries. Rome and Hellenistic Egypt As mentioned earlier ancient Rome was a case where the rules did not favour productive entrepreneurship. The Romans had the knowledge but did not put their technology to economically productive use. Some of the explanation for the lack of productive entrepreneurship is to be found in the rules of the game which severely discouraged productive entrepreneurship to acquire wealth. 3 Johan Mayer-Kjarby Medieval China In China the rules did not favour productive entrepreneurship. There was no individual freedom and no security for private enterprise, no legal foundation for rights other than those of the state, no alternative investment other than landed property. But perhaps the supreme inhibiting factor was the overwhelming prestige of the state bureaucracy, which maimed from the start any attempt to be different and innovate. The High Middle Ages Perhaps the hallmark of this industrial revolution was the remarkable source of productive power, the water mills. In sum the industrial revolution of the 12th and 13th century was robust and it is plausible that improved rewards to industrial activity had something to do with its vigour. The Fourteenth Century Retreat The end of all this period of buoyant activity has a variety of explanations. Temperatures dropped, the plague returned, the church clamped down on new ideas. Furthermore the fourteenth century included the first half of the devastating Hundred Years’ War. Remark on “Our” Industrial Revolution All the causes for our industrial revolution can hardly be fully discovered. The continued association of output growth with high financial rewards to productive entrepreneurship is suggestive even if it can hardly be taken to be conclusive evidence of proposition 3. 5. On Unproductive Avenues for Today’s Entrepreneur Some unproductive entrepreneurship of today: Rent seeking, tax evasion efforts and arbitrageurs 6. Changes in the Rules and Changes in Entrepreneurial Goals A central point in this discussion is the contention that if reallocation of entrepreneurial effort is adopted as an objective of society it is far more easily achieved through changes in the rules that determine relative rewards than via modification of the goals of the entrepreneurs and prospective entrepreneurs themselves. There exist testable means that promise to induce entrepreneurs to shift their attentions in productive directions without major change in their ultimate goals; to increase their wealth. 7. Concluding Comments A expansion of Schumpeter’s theoretical model to include the allocation of entrepreneurship is not without substance. The rules of the game specify the relative payoffs to different entrepreneurial activities and can significantly affect the vigour of the economy’s productivity growth. Jämför USA och Japan. I Japan är det betydligt färre stämningar i konkurrens mål p.g.a. av annat regelverk. Slutsatsen är att vi inte behöver vänta på en långsam kulturell förändring för att göra entreprenörskapet mer produktivt. Det räcker att vi ändrar spelets regler på rätt sätt. 4