There`s More to Medical School Admissions than Organic

advertisement

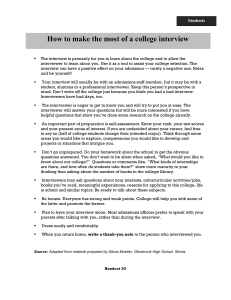

Less Is More There's more to medical school admission than organic chemistry. Paul Jung, M.D. In the last column, we discussed the issue of selecting a college major, discussing how humanities majors have a statistically higher chance of getting in to medical school. We also addressed choosing extracurricular hobbies in order to cement your "unique individuality." Let's continue this theme and focus on the idea that less is more. For example, many applicants not only (mistakenly) try to stack the cards in their favor by choosing a science major, but they also believe that by packing their transcripts with extra science courses, they may strike a chord with sympathetic admissions committees. But they fail to realize the beneficial, if less tangible, advantages of the wellrounded curriculum. More Is Not Better. Dead set on beefing up his transcript, one premed once abandoned a summer to take more science courses. His heroic reason: "I need a higher GPA [grade-point average] to get into medical school." I sat him down with a calculator and showed him that he would need A's in three fourcredit lab courses to improve his GPA by a mere 0.1 point. Considering the work required in such a bulging course load, it was not surprising that he didn't get the three A's. If a higher GPA is the Holy Grail of premedical students, the question must be asked, "At what price?" College is four years long, and medical school requirements are a modest selection of science courses. If more science courses result in more qualified medical students (and ultimately better doctors), medical schools would obviously require them. But they don't, so we must assume that taking science courses over and above the minimal requirements should be only for one's personal preference, not to impress admissions committees. Quality is always far more important than quantity in this case. You should shoot for the best grade possible in the required courses. Success in them relieves you of the "extra science crutch" that props up many failed applications. If an applicant is seriously considering heaping science courses on his transcript (and thereby eliminating all other possible educational opportunities), he must answer these two questions first: What science GPA am I shooting for? And How many A's in how many science credits will I need to achieve this GPA? You'd be surprised at the answers. There may be only one instance when more science courses can benefit a student-when performance in the basic required courses is miserably substandard. In this case, the only solution is to prove your academic mettle by taking upper-level science courses and earning A's in them. But be careful. Few students are successful at this strategy (doing well in more difficult courses isn't easy after a lousy performance in a basic course). And retaking the same course serves no purpose, because you're risking obtaining the same poor grade, if not worse. Also, regardless of how your college may compute your GPA, the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS)-the required method of medical school application-does not replace one grade for another but averages both grades into the final GPA. Remember, there's plenty of room within the basic required courses to show improvement; better grades in organic chemistry will surely ameliorate concerns arising from mediocre general chemistry scores. No need to crowd out the opportunity to learn some history or philosophy (which you will never have the opportunity to learn formally again) in a misguided attempt to bump up your GPA by a mere fraction. But let's say you do well in your basic prerequisite courses, even score A's in all of them. Extra science courses are not helpful in this situation, either. Some eager premeds mistakenly assume that mastering advanced science coursework in college will help them get ahead in medical school. If this were so, medical schools would encourage it or give advanced standing to the exceptional student who has succeeded in this regard. This is not the case, and for good reason, too. Remember that the point of an undergraduate education is not simply to prepare you for medical school by expanding your repository of memorized science factoids but rather to prepare you for life as a physician by broadening your mind and honing your sense of humanity. There will be no other time in your life when you can take courses and interact with students and faculty on such a wide variety of subjects. Don't waste your time secluded in a science lab for some narrow-minded and ultimately selfdestructive attempt to simply get into medical school. An admissions director at a prestigious medical school once told me that he could fill his entire entering class with 4.0s in biomedical engineering or entirely with Ph.D.s. This is exactly what makes admissions decisions so difficult-medical schools are trying to find a diverse body of students with various backgrounds and experiences; excellent grades are by no means your sole ticket to admission. Admission to medical school must not be considered merely a reward for perseverance and cutthroat intelligence. Rather, it must be considered admission to a school, where you will be taught what you need to know to become a physician. Reserve your time in medical school for these medical sciences, and use your time in college to broaden your mind. With a proper undergraduate education and a variety of experiences under your belt, you'll be better prepared to cruise through the next step of the application, your admissions interview. The Interview. How important is it? They say that the final decision is actually made in the first minute of the interview, and the other 29 are used to validate that decision. This is true in a corporate job hunt as well, and it gives us several clues on how to succeed in the interview. If the first minute is most important, then first impressions are paramount. And the first impression you will make is with your appearance. Many of you may think that appearance should not matter, but it remains a significant factor in how you are judged, if only subconsciously, whether you like it or not. So dress conservatively; a well-pressed navy blue or gray business suit with a standard tie for men and a suit or dress for women. Anything stylish to you and your friends may only be considered flamboyant to others, especially stodgy, older medical school admissions faculty. If you truly believe that looks should not matter, then prove it by dressing appropriately. This should prevent the admissions committee from discussing your dress and allow them to focus on your qualifications. The interview is an integral part of the application process. Medical schools use this meeting to gauge your nonacademic people skills. And studies have proven that higher interview scores correlate with better medical school performance. There are occasional stories of premeds with below-average applications who somehow made it to the interview, performed extremely well and subsequently got in. What types of questions should you expect? Some may ask standard bread-and-butter queries like, "Why do you want to be a doctor?" These are more typical in blinded interviews, where the interviewer hasn't seen your application. Others may ask specific questions about your application that focus on your hobbies or academic pursuits. Consider this a golden opportunity to present yourself as a unique individual. Some interviewers prefer the psychological game and try to intimidate you or ask unanswerable questions. Don't be flustered-just answer as best you can, be honest and move on. But mostly, your interviewer will just want to shoot the bull and talk about last night's game or what the president did last week. Again, engage yourself and join in. Prove that you are aware of the outside world and how it affects people. But don't go too far. There are plenty of stellar transcripts that got ditched after a bombed interview. One cocky applicant listed "wine tasting" as a fabricated hobby on his application. His interviewer, himself a wine aficionado, asked what the candidate thought of 1993 Chilean wines. The applicant began discussing the merits of Chilean wines from 1993 until the stern interviewer interrupted him and said, "Son, there were no wines from Chile in 1993. This interview is over." Instead of lying, having a few questions at hand may help you through the dead space in the interview. Easy questions to ask include "How well do your students do on the boards?"; "How well do your students do in the Match?"; "How flexible is your curriculum?"; "What are the school's curricular innovations and special programs?" and "How good is the financial aid at this school?" It will behoove you to ask these questions of the school's medical students as well, to make sure that their experience matches with what the faculty and administration tell you. The medical school interview is a way to not only gather information about the school but also an occasion to sell yourself and your unique individuality. Take advantage of this opportunity. It may be your best and only chance.