Published - Office of Administrative Hearings

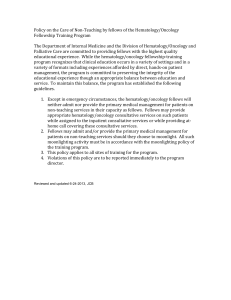

advertisement