Sustainable Organizing: A Multi

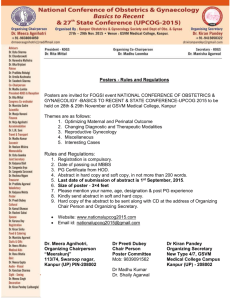

advertisement

Sustainable Organizing 1 Sustainable Organizing: A Multi-paradigm perspective of Organizational Development and Permaculture Gardening Graduate Student Submission to MW AOM 2011 Abstract As organizations focus on survival in an ever-changing environment, principles that lead to sustainability and resilience are most desired. Discourse on organizations has transcended adaptation, presented in contingency theory, and moved onto growth, flourishing, and resilience. Sustainable organizing supports organizational flourishing and yields positive outcomes for a system of organizations. To support the proposed theory of sustainable organizing, a 120-day action research case is featured. The findings of the case suggest that the application of permaculture gardening techniques, applied to human systems, will yield sustainable organizing which renders a thriving and resilient ecosystem. The primary objective is to contribute a theory of sustainable organizing that supports organizational flourishing and yields positive outcomes for a system of organizations. Keywords: sustainable organizing; high quality connections; flourishing 1. Purpose and Research Questions The theory of sustainable organizing is built from a multi-paradigm perspective (Gioia & Pitre, 1990) that draws from scholarship on organizational development and permaculture gardening. The proposed theory contributes to the practice of organizational development by providing a point of departure for engaging a system of organizations. Sustainable Organizing 2 In the Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), Thomas Kuhn introduced the concept of a paradigm. From its inception, the concept has been vague and difficult to specify. For the purpose of this discussion, a paradigm is one of several frames of reference within a field of practice. It encompasses the set of assumptions and common views informing professional practice. These commonalities include theorems, proofs, axioms, principles, laws, methodology, shared agreement on the problems of a field, and scope of the field. Kuhn concluded that changing paradigms allows people to view their surroundings in new and different ways. The change in thinking proposed here is that the principles of permaculture gardening (Mollison & Holmgren, 1978; Mollison & Slay, 1992; Mollison, 1990; Hart, 1996; Holmgren, 2002; Jacke, 2005; Holmgren, 2007), applied to human systems, can produce sustainable organizing, which leads to organizational flourishing and yields positive outcomes in a system of organizations. As the term sustainable has become an elusive buzzword, we adhere to a definition of enduring. A 120-day action research case supports the theory. During the implementation of this case, the authors co-facilitated a plan for a sustainable permaculture garden situated at the intersection of a number of loosely coupled organizations. As Weick (1976) noted, loose coupling carries connotations of impermanence, dissolvability, and tacitness, all of which are potentially crucial properties of the glue that holds organizations together. The challenges of this loose coupling, along with the commitment to establish a sustainable organization, led to the primary research question: When faced with a network of organizations, which practices will best establish and sustain a vibrant garden supported by high quality connections (HQCs)? From an ontological point of view, we view organizations as complex responsive processes (CRP) (Trist, 1983; Trist & Bamforth, 1951) that are socially constructed (Berger & Sustainable Organizing 3 Luckman, 1966). Because of the emergent nature of reality in CRP, there is a deficit of methods to support and encourage organizational thriving. Drawing from existing literature and the featured case, this article fills that gap with a set of tools and processes that support sustainable organizing. We situate the theory of sustainable organizing in Positive Organizational Scholarship. 2. Literature Review Literature from complexity theory is first explored. Second, positive organizing theories including: high quality connections (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003), positive emotions and upward spirals in organizations (Fredrickson, 2003), and Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider & Sekerka, 2003) are explored. Finally, as a result of the action research consultation involving the creation of a garden, the relationship between humans and their natural environment is explored through a review of selected literature from the fields of ecopsychology and permaculture gardening. 2.1 Complex Responsive Processes In the past century, the discipline of organizational development has shifted from linear models (F. A. Taylor, 1911) of planning and control, to processes in constant flux and transformation (Bohm, 1980; Gleick, 1987; Morgan, 1998). Viewing organizations as complex responsive processes offers a radically different perspective on the nature of organizations (Stacey, Griffin & Shaw, 2000, p. 183; Stacey, 2001, p.p. 51-89; Fonseca, 2002; Griffin, 2002; Griffin & Stacey, 2005; Shaw, 2002; Stacey, 2002, 2005; Streatfield, 2001). The concept of emergence became prominent in the nineteen nineties with the advent of complexity theory (R. Lewin, 1993; Waldrop, 1992) and is now recognized as a defining property of complex systems. Complexity theory suggests that if there is enough connectivity between the actors in a system, a new order will emerge spontaneously (Goldstein, 1999). Sustainable Organizing 4 Critchley and Stuelten (2008) describe organizations as dynamic social processes of communicative interaction. Communication is broadly defined and includes any form of gesture and response between at least two people, making the quality of relationships and of communicative processes the key factors in the quality of organizations that emerge. While the quality of relationships within organizational systems requires deliberate acts of maintenance, too much stability will result in a loss of vitality. When this happens, it becomes the role of managers and OD practitioners, as facilitators of CRP, to deliberately disturb the relational patterns, allowing new patterns to emerge and creating a sense of aliveness. Stacey (2002) suggests that leaders and OD practitioners operate most effectively by focusing on ‘what is’ rather than ‘what should be’. He suggests that reflective conversations, where participants engage with the emerging organization and their perception of it, are a powerful tool for surfacing the immediate reality. Active engagement in the conversation, Stacey suggests, will inevitably alter what emerges. CRP is a manifestation of the constructionist principle, which suggests that as we talk, so we make (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005, pp. 49-50). Additionally, CRP draws attention to a shift in the role of the OD practitioner as an external and objective intervener to a participant. As Critchley and Stuelten (2008) suggest, OD practitioners come into an organization with their own beliefs and prejudices, which affect the organization. In return, the perspective of the OD practitioner is also formed by the organization. Extending this social construction, recent findings from ecopsychology and the authors’ experience during the case suggest that this interactive process also takes place between human and natural systems. Critchley and Stuelten (2008) perceive a clear difference between natural phenomena and social phenomena, the latter emerging as humans interact with one another and with their Sustainable Organizing 5 environment. They conclude that unlike natural phenomena, social interaction cannot be reduced to mathematical formulas. Based on this distinction, they set CRP apart from all other theories that have offered insight about the nature of human organizing based on examples found in nature. It is this assumption that the theory of sustainable organizing questions. We contribute an alternative point of view, one in which emergence can be fostered through high quality connections between humans and their natural environment. 2.2 High Quality Connections, Positive Emotions and Upward Spirals in Organizations, and Appreciative Inquiry The theory of sustainable organizing also draws on three constructs from Positive Organizational Scholarship: 1) High Quality Connections (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003); 2) Broaden and Build Theory (Fredrickson, 2001); and, 3) Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider, 1990). These three constructs are central to understanding the intensity and the quality of the interactions within a system. 2.2.1 High Quality Connections. Dutton and Heaphy’s (2003) High Quality Connections construct offers insight on fostering higher levels of connectivity, which is defined by the number of interactions between agents within a system and the positivity of these interactions. They describe the quality of a human connection in terms of whether the connective tissue between individuals is life giving or life depleting. Life giving tissue has three defining characteristics: a) higher emotional carrying capacity: the capacity to withstand a higher intensity of emotion and a greater variety of emotional expression; b) greater tensility: the capacity of the connection to bend and withstand strain, such as occurs during conflict (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003); and, c) a higher degree of “generativity,” the capacity to “dissolve attractors that close possibilities and evolve attractors that open possibilities” (Losada, 1999, cited in Dutton & Sustainable Organizing 6 Heaphy, 2003). Subjectively, HQCs are experienced through feelings of vitality and aliveness, a heightened sense of positive regard, and the sense that both people in a connection are engaged and actively participating. These subjective affective experiences are “important barometers of the quality of the connection between people” (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003, p. 267). While the focus of the HQC construct is on the quality of the connection, Dutton & Heaphy (2003, at p. 272) report that scholars who explore human connections for their role in facilitating human growth have identified a link between the quality of a connection and the frequency of interaction. The theory of HQC’s offers insight into sustainable organizing by supporting frequent positive interactions between actors in systems. “[P]sychological growth occurs in mutually empathic interactions, where both people engage with authentic thoughts, feelings and responses. Through this process they experience mutual empowerment, greater knowledge, sense of worth, and a desire for more connection” Dutton & Heaphy (2003). 2.2.2 Broaden and build theory. Recent research on the impact of positive emotions have shown that they can help people flourish (Fredrickson, 2001, 2003; Staw & Barsade, 1993; Staw, Sutton, & Pellod, 1994). Frederickson’s “broaden and build” theory explains how positive emotions broaden people’s modes of thinking and action, which over time builds their resources, ranging from physical and intellectual to social and psychological (Fredrickson, 2001). Positive emotion experiences such as joy, interest, pride, contentment, gratitude, and love, can be transformational and fuel upward spirals toward individual flourishing (Fredrickson, 2003). Individual upward spirals can, in turn, lead to organizational flourishing (Fredrickson, 2003). Fredrickson suggests that this happens through pathways of emotional contagion (J. M. George, 1991; Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1993; Quinn, 2000), increased corporate citizenship and generally pro-social behaviors (J. M. George, 1991, 1998; Isen, Daubman, & Sustainable Organizing 7 Nowicki, 1987), pride (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2001) and gratitude (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). They can also be triggered by feelings of elevation (Haidt, 2000, 2003) stimulated by observing helpful behaviors in others, or by the reduction of conflict (Baron, 1993). Fredrickson concludes that positive emotions can transform organizations because they broaden people’s habitual modes of thinking, and in doing so, make organizational members more flexible, empathic, creative and so on. Emotions typically follow appraisal of personal meaning. Thus, if organizations want to foster positive emotions in individuals, they should create a work context that allows individuals to derive personal meaning from experiences of “competence, achievement, involvement, significance and social connection” (Fredrickson, 2003). As described above, HQCs between humans at work are one way to foster meaning. We suggest that the facilitation of connectivity with nature at work offers another pathway to elicit physiological, affective and cognitive positive spirals that broaden the human thought-action repertoire and that the HQCs created with nature lead to HQ social connections and to greater connectivity within a human system. 2.2.3 Appreciative Inquiry. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is an organizational development and change process designed to value, prize, and honor. Similar to the theory of organizations as CRPs, AI assumes that organizations are networks of relatedness, and that these networks are alive (Cooperrider & Sekerka, 2003, p. 226). Based on the constructionist understanding that humans systems will evolve in the direction of questions that are asked, AI aims to discover the positive core of organizations by asking positive questions. In this way, AI directs emergence towards the desired positive outcome. AI is a process designed to connect a system with more of itself, a strategy recommended by Margaret Wheatley (2007, pp. 93 and 106) for pursuing greater health of a human system. AI Sustainable Organizing 8 does this by engaging as many people as possible in the process of discovering the organization’s positive core. This process not only generates connectivity between individuals through shared exploration of what gives life to an organization, but also imbues these connections with positive emotions generated as a result of the focus on the live-giving qualities within the organization. Hope grows and community expands (Cooperrider & Sekerka, 2003, p. 227). During the second stage of the AI process, the articulation of a shared future vision creates high levels of connectivity around a passionately shared purpose (Quinn, 2000). The contribution of AI to the speed of emergence becomes clear in the third phase, the design phase, of the AI process. When people share a vivid dream of the potential of their organization, they are far more likely to cooperate in designing a system that might make that dream a reality. During the final phase of the AI process, the destiny phase, top-down implementation strategies are abandoned in order to create room for emergence of self-organizing network-like structures. A convergence zone is created for people to empower one another, to connect, co-operate, and co-create. Changes never thought possible are suddenly and democratically mobilized when people constructively appropriate the power of the positive core (Cooperrider & Whitney, 1999: 18). 2.3 Ecopsychology As was suggested above, positive emotions can also be nurtured through high quality connections between human beings and natural systems. One of the deliverables of the action research case was the production of a research paper that touts the benefits of a garden to a network of organizations associated by physical proximity. This research uncovered pathologies created as a result of human separation from nature. It also uncovered multiple benefits of humans close connection with nature. As the authors studied these positive effects, we realized Sustainable Organizing 9 that we ourselves were experiencing them as a result of our evolving relationship with nature and the garden we were co-creating. The qualities of these effects felt very similar to the effects Dutton and Heaphy described as triggered by HQCs between human beings. We believe that the high quality connection between the co-creators of the garden and the garden itself created a broad range of positive individual outcomes, which in turn contributed to greater connectivity between the people in the system and the overall flourishing of the system. Numerous studies suggest that mere visual exposure to nature can dramatically improve behavioral and performance outcomes for groups such as prisoners, patients in hospitals, and children in schools (Hartig, Mang, & G. Evans, 1991; R. Kaplan & S. Kaplan, 1989; S. Kaplan & Talbot, 1983; Katcher, Freidmann, Beck, & Lynch, 1983; Moore & Wong, 1997; Orians & Heerwegen, 1992; Ulrich, 1984; Ulrich et al., 1991; Wells & G. Evans, 2003). Of particular interest is the experience of mutuality as a marker of HQCs. This sense of mutuality is also cited as an outcome of a deep connection between humans and nature. Humans receive positive physiological, emotional, cognitive, social and spiritual benefits while nature in turn receives the benefits of human protection and stewardship (Chawla, 2002; Louv, 2008). The pathways by which these benefits accrue to humans are cognitive, emotional, physiological and social. Rachel and Stephen Kaplan (1989) conducted research in the field of attention-restoration and found that people concentrate better after spending time in nature, or even looking at scenes of nature. They describe experiences of regarding clouds moving across the sky, leaves rustling in a breeze, or water bubbling over rocks in a stream, things a person can reflect upon in effortless attention (Rachel Kaplan & Stephen Kaplan, 1989). Architect Simon Nicholson’s loose-parts theory correlates “the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery, to the number and kind of variables in an environment” (Nicholson, 1971). Sustainable Organizing 10 The findings from both physiological and self-report measures of a 1991 study on the impact of exposure to natural views following a stressful event support the idea that recuperation from stressors will be faster and more complete when individuals are exposed to natural rather than various urban environments (Ulrich et al., 1991). Ulrich found that people who watch images of natural landscape after a stressful experience calm markedly in only five minutes. Physiologically, their muscle tension, pulse, and skin-conductance readings plummet. In The Human Relationship with Nature, Peter Kahn (1999) points to the findings of over one hundred studies confirming that one of the main benefits of spending time in nature is stress reduction. Leather, et al (1998) have shown that a view of natural elements such as trees, plants, and foliage buffer the negative impact of job stress. Farley and Veitch (2001) have established a positive correlation between windows at work and employee well-being. Cetegen, Veitch and Newsham (2008) isolated view, size, and office luminance as key qualities of windows that contribute to employee satisfaction. A study of the impact of indoor plants in a windowless work place revealed that participants were more productive (12% quicker reaction time on the computer task) and less stressed (systolic blood pressure readings lowered by one to four units) following the addition of plants to their workspace. Participants in the room with plants reported feeling more attentive (an increase of 0.5 on a self-reported scale from one to five) than people in the room with no plants (Lohr, Pearson-Mims, & Goodwin, 1996). From the social perspective of connectedness to other human beings, shared gardens offer a pathway for community development and cohesiveness. They also create bonds that feedback to support emotional well-being (Capra & Stone, 2010). As Pfeffer (2009) noted, organizations Sustainable Organizing 11 are made up of people and thus sustainable initiatives should consider organizational effects on the social world as well as the physical environment. 2.4 Permaculture Gardening The contraction of the words “permanent” and “agriculture” is credited to the mid-1970’s collaboration between Australians David Holmgren and Bill Mollison (1978). Their approach, merging systems thinking and design, is less their invention than their observation. The interlocking ecosystem of plants, insects, and animals is a fundamental reality of life on Earth, sustaining human life while it waits to be discovered as an inspiration for sustainable design of all sorts. In the theory offered, it is adapted to organizational development processes. Permaculture gardening is centered on a particular cultivation and design methodology, one which uses nature as its model and strives to create a designed ecosystem modeled on natural patterns, maximizing output (food production) while minimizing input (Mollison & Holmgren, 1978; Mollison & Slay, 1992; Mollison, 1990; Hart, 1996; Holmgren, 2002; Jacke, 2005; Holmgren, 2007). These characteristics are the essence of sustainability in biological ecosystems. Holmgren extracts the following twelve design principles from his study of natural ecosystems: 1) observe and interact; 2) catch and store energy; 3) obtain a yield; 4) apply self-regulation and accept feedback; 5) use and value renewable resources and services; 6) produce no waste; 7) design from patterns to details; 8) integrate rather than segregate; 9) use small and slow solutions; 10) use and value diversity; 11) use edges and value the marginal; and, 12) creatively use and respond to change (Holmgren, 2007). 3. Methods We were aware of the theoretical contributions of Dutton, Cooperrider, and Frederickson before we embarked on this project. We deliberately employed the practices they suggested that Sustainable Organizing 12 lead to flourishing organizations. We organized ourselves in relationship to the client-system drawing from the theories of these practitioners. When we actually started developing the garden, we experienced peace, quiet, elevation. These physiological and emotional reactions were the result of the deep connection with the natural systems, facilitated by HQC, AI, and positive spirals. A meta-level attention to these theories allowed us to observe the relationship of human actors involved in the change process with the natural system. 3.1 Setting This case examines a small community of organizations linked by geographic proximity and a common purpose. The stakeholder organizations include: a home for the elderly (corporation), a charter grade school (education system), a center for creative aging (not for profit), and a center for ecological culture (not for profit). Additionally, the case aligned with the local urban farming initiative and suggested promising outcomes for the surrounding community. The leaders of the respective organizations had agreed to develop a part of the shared campus into a permaculture garden. Their vision was a garden that would produce unique benefits to each of the stakeholder groups, the community, and the city, as well as link the organizations in new and unforeseen ways. This, it was thought, would encourage innovation and inter-organization collaboration. The benefits proposed included curriculum development, food yield, intergenerational interactions, land beautification, spiritual health, and holistic well-being. The leaders of the respective organizations also planned to co-create and co-manage the garden. 3.2 Research design A team of six researchers, four of whom are the authors of this paper, were invited to develop a sustainable organization plan for the garden. The researchers collaborated with two lead clients: the Director of the Center for Creative Aging and the Director of the Center for Sustainable Organizing 13 Ecological Culture. The lead clients were accessible, engaged, and passionate project participants. Their energy was evident from the beginning of the project. The researchers held numerous meetings with the lead clients during early stages of the project. These meetings established a shared understanding and purpose which, as Hinrichs (2009) has suggested, led to commitment and served as a linking and coordinating mechanism through the conclusion of the researchers’ role and beyond. The researchers employed an action research (K. Lewin, 1948) methodology consisting of iterative stages of diagnosis, planning, action and fact finding. 3.3 Planning The research team initiated the project with excitement, curiosity and high expectations for client-system impact. The 120-day engagement was divided into four phases: 1) information collection and discovery; 2) preparation and data gathering; 3) analysis; and, 4) report delivery. Each team member was designated to a stakeholder group. A contract that outlined the project timeline, objective, scoping diagram, deliverables, plan of action, resource list, logistics and client and OD practitioner responsibilities was submitted and approved by the client. The researchers leveraged team diversity, which fostered greater learning, growth, creativity and overall effectiveness. The team consciously played to their strengths, which improved both team performance and member satisfaction (Buckingham & Clifton, 2001). As Knippenberg (2007) suggests, diverse groups are likely to possess a broader range of taskrelevant knowledge, skills, and abilities which gives diverse groups a larger pool of resources that are beneficial in dealing with non-routine problems. 3.4 Data Collection and Analysis Research was focused on the intersections of education, health, wellness, intergenerational interaction, and community in the context of the garden. The team was Sustainable Organizing 14 dedicated to highlighting these rich and life-giving benefits of the garden that were lying dormant and waiting to be discovered. As awareness grew, so did the connections and interactions. Data was collected through literature review, bi-weekly onsite client meetings, conference calls, interviews and garden events. The researchers worked with stakeholders to develop a new course of action to help the community improve its work practices. As Peter and Robinson have suggested, “as human beings become active in constructing social reality, they can also act to change it for the better” (Peter & Robinson, 1984). Telephone and on-site interviews with schoolchildren, schoolteachers, parents, administrators, and elderly home residents were conducted throughout the project. The focus of the interviews was on meaning making and soliciting future engagement using AI. Questions such as, “If you were a fruit or vegetable in the garden, what would you be?” and “What is your greatest hope for the garden in ten years? What will you have done to contribute to this vision?” The personification of a vegetable or fruit gave insight into what an individual might contribute or offer to a larger human system. One respondent answered, “I think I would be a lemon, because they are colorful and bright and give a sense of cheer and joy to people looking at them.” Another responded, “I would say broccoli, nobody likes broccoli, but it is very healthy and has a great color”. In addition to meaning making, appreciative questions expanded people’s sense of what is possible (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, 2008). Garden work parties drew attendees from multiple stakeholder groups, who shared an understanding and conviction to the purpose (Hinrichs, 2009). These events promoted bridge building and connections between stakeholder groups, as well as between the primary stakeholders and the research team. The high degree of connectivity fostered an atmosphere of buoyancy, creating expansive emotional spaces that opened possibilities for action and creativity Sustainable Organizing 15 (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003). This connectivity also created social capital (Putnam, 2000), the collective value of social networks and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other. Events were promoted by email, neighborhood canvassing, and a flyer circulated throughout the stakeholder network. Research team members reached out to their respective stakeholder group to maximize participation. The experience was meaningful and enthusiasm was contagious. Enthusiasm also spread when stakeholders shared inspirational stories from the garden with their respective stakeholder group. Data gathering also included photo and video documentation that chronicled the transformation of the garden. Often, visual images spark more intense emotions than words. These images allowed researchers to see what may not have been seen in the first place (King, 2010) and enhanced the dispersed team process by keeping remote members connected to the action and progress on the ground. Distant researchers (two members of the research team) were able to visualize the progress in a deeper way than a shared narrative alone would have allowed. The project photos and videos were stored on a public project website. The site memorialized and revealed the transformation as it occurred. It also served to seed further connections and conversations, as well as a sense of participation in the meaning-making process (King, 2010) throughout the project and beyond. A second, public website was created to support the client in sustaining the edible forest garden. This site included the literature review, links to exemplar sites, and inspiration, as well as the photos and videos recorded throughout the process. This site served to foster on-going public relations and dialogue for the intersections of education, intergenerational interaction, health, wellness, and community in the context the garden. Additionally, the researchers leveraged a workshop at the garden that was conducted by permaculture expert, Dave Jacke. The team observed the workshop and actively promoted the Sustainable Organizing 16 high profile event, which served as a powerful project anchor by attracting a wider network of passionate participants and spreading the word of the garden. The researchers’ official involvement with the project ended with client-system report outs on the campus. The entire research team, clients, teachers, parents, elderly home residents, students and project team family members attended the event. It was a moving day filled with positivity, optimism, and hope. A successful transfer of responsibility from the researchers to the client was achieved. The culmination of exhaustive research, digging in the dirt, and the power of HQCs created during the project was felt and sensed, with lasting implications for all participants. According to Fredrickson, “…the personal resources accrued during states of positive emotions are conceptualized as durable. They outlast the transient state that led to their acquisition. By consequence, then, the often-incidental effect of experiencing a positive emotion is an increase in one’s personal resources. These resources function as a reserve that can be drawn on in subsequent moments and in different emotional states” (Fredrickson, 2001, p. 220) There was a sense of sustained commitment and energy in the air. The research team and clients both knew this was much more than a well-executed project. There was no doubt that the energy would sustain due to the quality of work, extensive data gathering and analysis, project meaning and the intentional efforts to create transferrable deliverables that would broaden and build the thought repertoires of all involved (Fredrickson, 2001). The deliverables serve as an impetus for multifaceted action including further permaculture and intersection research, establishing community gardens, and local and global attention. Sustainable Organizing 17 4. Results and Findings The results and findings in this study exist at multiple levels. At one level, the literature review facilitated a simultaneous investigation of complex responsive processes, positive organizational scholarship, and permaculture gardening. Each of these provided a unique perspective on the client request to develop sustainable organizing around the garden. At a deeper level, applying the insight gained through the literature review to an immediate client need provided an opportunity to test insights in evolving human organizations. Beyond the rapid learning cycle that this immediate application created, the experience of participating in the system of organizations while developing this system created an even deeper learning environment for the researchers. Beyond the learning opportunity, immersion in the client system gave the researchers a view from both ends of the microscope, studying the developing organization while being part of the organization that was developing. The researchers’ uniformly reported personal experiences of aliveness, presence and buoyancy as a result of being in the garden. Several members of the team described the sense of calm and serenity experienced through interaction with nature. They also uniformly reported an experience of high quality connections with one another and with the two lead clients. Additional evidence in support of the theory exists when comparing researchers’ reports of their experience with the combination of other life circumstances that existed simultaneously with the project. In addition to the stress of pursuing graduate education while working full-time, each member of the team had other life stressors occur during their participation in this case. In the midst of all the stress arising from life events, the team’s positive reports of their experience take on even more significance. Reports from researchers about their experience, along with their ongoing interest in working together, support the theory that sustainable organizing is enabled at Sustainable Organizing 18 the intersection of complex responsive processes, positive organizational scholarship, and permaculture design principles. The key findings of this case are an extension of Holmgren (2007) twelve permaculture principles. These principles, adapted to human systems, build the theory of sustainable organizing. While the permaculture and design principles are the work of Holmgren (2007), the application of these principles to human systems is the work of the authors. 4.1. Observe and Interact Of this principle, Holmgren says, “Facilitating the generation of independent, even heretical, long-term thinking needed to design new solutions is more the focus of this principle than the adoption and replication of a proven solution” (Holmgren, 2007). He further says simply copying models of land use already existing in our culture will stifle the creativity needed for real solutions. The techniques that work on one combination of land, plants, and people may not work with a different combination. This design principle may be the most important one for sustainable organizing. Without observation and interaction, even the most perfectly conceived plan will outlive its functionality and usefulness. Organizations are sustainable because they evolve and adapt. Vigilant observation and interaction by and with all stakeholders will ensure maturity, growth, evolution, and adaptation. 4.2. Catch and store energy Plants collect energy from the sun and store it as biomass, making it available for later use. In human organizations, the transfer and storage of energy is just as complex, but is likely more difficult to define. Groups of people, like the individuals in them, find themselves most vibrant and alive when their activities are most closely aligned with their mission and purpose. Sustainable Organizing 19 The application of this design principle is to align each organization’s involvement as closely as possible to their respective core mission. This requires each stakeholder organization to be involved as soon as possible in imagining and planning the initial and future states. Beyond that, it requires communication to develop and be customized for each of the stakeholder groups, incorporating the language of a given group’s mission, vision, and values into the communication, and connecting activity to the source of each organization’s energy. In the case featured in this article, each stakeholder group was able to pursue an application of their common activity to accomplish their purpose in the context of the garden. The school gained a live learning lab for science and social education. The center for creative aging gained another point of interaction for elders and children. The center for ecological culture gained an exemplar of multiple stakeholder groups collaborating with one another and with nature to achieve a self-sustaining environment. As involvement with the garden helped each organization move closer to its mission, the energy of mutual benefit and accomplishment accumulated and fed itself. 4.3. Obtain a yield Beyond simply explaining activities in terms of each organization’s mission, vision, and values, involvement must produce observable results. The task of obtaining and measuring a yield is straightforward for garden production. It becomes much more complex to measure the differential impact of garden participation on health, education, or personal development. Even with these complexities, sustained participation will most likely occur when garden engagement is manifesting respective goals of the partner organizations. Follow-up conversations with the client-system indicate a sustained yield of interest and involvement. Seven months after the project closed, one of the clients commented “I am in DC at Sustainable Organizing 20 AARP, EPA and other green organizations literally presenting the garden and related programs today and the virtual garden and related programs tomorrow… so your efforts are being well watered and are growing well.” (Whitehouse, 2011) 4.4. Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback Tied to observe and interact, apply self-regulation and feedback allows a system of organizations to evolve in a stable way. Self-regulation consists of formal articles of incorporation, by-laws, and governing principles of the partnership. Possible provisions for feedback include a rotating board of directors or a system of voting. Less formal feedback loops include scheduled surveys or interviews of stakeholders and curriculum elements that provide research opportunities for students to collect feedback from garden participants. The researchers’ work helped establish the need to cultivate elements of formal organizing. Rather than define these as part of the outcome of the research, the team worked to demonstrate the need for these elements and to set a framework in place within which the organizations could organically pursue them. In doing this, the researchers encouraged cocreation among the stakeholders consistent with the metaphor of the garden. The interview protocol created as part of the project also established a framework for gathering feedback from garden participants in the future. 4.5. Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services Observation of natural ecosystems reveals that life on Earth is dependent on cycles. The carbon cycle traces the path of carbon from the atmosphere through the metabolism of organisms. The water cycle traces the path of water through precipitation from the atmosphere to the ground, to streams and rivers, collecting in reservoirs and oceans, only to evaporate into the atmosphere and precipitate again later. Sustainable Organizing 21 In the organizational sense, the renewable resource is the people involved in sustaining a network. If the network is thoroughly integrated there will be an ever-renewing source of people. 4.6. Produce no Waste In a biological ecosystem, this principle relates to the idea that the waste of every organism is food for another. In the ecosystem of a human organization, waste arrives in the form of purposeless activity, bureaucracy, or requirements that persist beyond their usefulness. The concern in biological ecosystems relates more to "how can I use waste." In human ecosystems, the more important question becomes, "How can I prevent or eliminate waste?" 4.7. Design from Patterns to Details Patterns in nature are recurring aggregations of details. These exist in human organizations as well. Dimensions of organizing people include division of labor (patterns associated with who does what: specializing or generalizing? simultaneous or in shifts? homogenous or heterogeneous combinations? dimensions of homo- or heterogeneity?) Combining this principle with observe and interact, along with apply self-regulation and accept feedback, leads to the conclusion that the selection of an organizational pattern is not static, but evolving as well. Top-down leadership will be the most effective approach at some times, while a more organic, grass-roots leadership will accomplish more at other times. The key is to intentionally choose and implement a pattern, then observe, accept feedback, and interact to change it when something different will accomplish more. The pattern applied to the emergence of the garden was to keep the two lead clients at the center of the action. They provided the vision and energy to drive the project forward, while the research team helped capture that vision in a way that could easily be shared with others. The Sustainable Organizing 22 research team’s focus on organizing people (volunteers, students, elders, faculty, and staff) also helped provide the patterns for organizing described above. 4.8. Integrate Rather Than Segregate Segregation in systems introduces waste. Biological cycles of life rely on the circulation of nutrients. Herbivores thrive by consuming plants, while their waste excretions provide nutrients to other plants that enable plant growth. By integrating living space of complementary organisms, it reduces the effort (or external intervention) required by both to thrive. Points of integration in human organizations occur at any point of difference: demographic differences, activity differences, role differences, responsibility differences, etc. Interdependence is a fundamental reality of life and integration across organizations, at any point of difference, provides an opportunity for personal and organizational growth that may not otherwise exist. The school in this case study is designed to make the most of age diversity. By creating intentional opportunities for interaction between elders and grade-school students, the school provides health benefits for elders while exposing the students to experience and insight that they might not otherwise access. Health benefits for elders from interacting with children are of particular interest to The Center for Creative Aging and have been the subject of studies by its director (D. R. George & Whitehouse, 2010). 4.9. Use Small and Slow Solutions Relationships between people grow from a collection of singular interactions. Trust is earned over time. Intentionally pursuing interaction and collaboration among stakeholders is the small, slow solution that builds relationships between human beings. These relationships are the organizational analog of the atom or the cell. The one-on-one connection of one person to another is the fundamental building block of sustainable organizing. Sustainable Organizing 23 The research team explored this dimension of human organizing through interactions with the primary client stakeholders. Following an initial face-to-face meeting, the research team continued to meet with the clients weekly. Local team members met face-to-face while remote members joined the meeting by telephone. The initial face-to-face meeting enriched the subsequent remote engagement, while the physical presence of local researchers served to gauge client reaction to the conversations, proposals, and plans for the project. Garden workday events provided a point of relational connection for the research team, the volunteers, and the primary client stakeholders as well. Personal interaction among participants created HQCs. 4.10. Use and Value Diversity Diversity is a unique characteristic of forest gardens as compared to industrial agriculture or traditional gardening. It is a fundamental element of the conception of the garden in this case study, which arose from the participation of multiple organizations. In this endeavor, the need to intentionally use and value diversity in the organizational sense arises not so much from the participation in the garden as in the ongoing leadership for the garden. Providing the diverse representation from each of the stakeholder organizations will be crucial. Ongoing leadership involvement from each of the stakeholder groups will insure that the garden supports the respective groups' objectives and will lead to better decisions by bridging multiple perspectives. The research team modeled the use and value of diversity through its division of labor for the project, leveraging individuals’ strengths as well as their physical proximity to (or distance from) the garden. They directly and indirectly facilitated collaboration among the various stakeholder organizations. Sustainable Organizing 24 4.11. Use Edges and Value the Marginal The garden itself is an edge environment because of its conception as the meeting ground for its constituent organizations' missions. This meeting of young and old, professional and recreational, therapeutic and educational, learning and teaching, all mirror the pattern of edge environments where sea meets soil, forest meets meadow, and shade meets sunlight. The research team modeled these values through the active engagement and inclusion of remote team members in the work of the garden. The team also actively engaged people in the neighborhood surrounding the campus by canvassing in preparation for the garden party and by engaging curious passers-by in conversation about the project. 4.12. Creatively Use and Respond to Change Change is inherent to living systems. It is a large part of what it means to be alive. Creatively using and responding to change, however, takes intentional effort. This principle loops the thought process back to the first design principle, observe and interact. It is through observation and interaction that change is first perceived, which is a necessary prerequisite to creative response. In the organizational sense, the influx and outflow of individual people is one of the most obvious forms of change. Whether a new tenant on the campus, new students in the school, or new elders in the retirement home, the flow of people through the garden will change with the seasons. The coming and going of individuals, with their varied perspectives, talents, and interests, is one of many opportunities to use change for growth and adaptation. Like the diversity and edge design principles, this principle is part of the fundamental conception of the garden. The plants of the garden flow through their individual lifecycles, germinating, maturing, and eventually dying. The different species have different lifecycles and their interaction over the long-term embodies change. The research team contributed to this Sustainable Organizing 25 change by connecting the primary clients with multiple stakeholder groups. Their documentation of the experience through the written report, photography of the site, and the promotional video can provide a catalyst to draw others into the garden, where they can change the landscape and be changed in the process. 5. Discussion, Limitations and Future Research As noted earlier, our research is looking to address the question: When faced with a network of organizations, rather than a singular organization, which practices lead to the creation and sustainability of a vibrant garden supported by high quality connections? The deliverables of this case serve as an impetus for multifaceted action including further permaculture and intersection research. We proffer that by investigating the intersection of organizations, we will begin to observe and recognize processes for sustainable organizing. The case highlighted in this paper evaluates the garden as an intersection. Others should further evaluate and research whether nature, as an intersection, has unique payoffs to sustainable human system organizing. It is thought that high quality connections with nature can create positive cognitive, physical, emotional and spiritual spirals. Other researchers should support this claim with further empirical evidence. Additionally, other forms of an intersection that produces unique benefits to each of the stakeholder groups should be researched. Sustainable Organizing 26 References Altemus, M., Redwin, L., Leong,, Y. M., Yoshikawa, T., Yehuda, R., Deterea-Wadleigh, S., & Murphy, D. L. (1997). Reduced sensitivity to glucorticoid feedback and reduced glucorticoid receptor mRNA expression in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Neuropsychopharmacology, 17, 100-109. Baron, R. A. (1993). Affect and organizational behavior: When and why feeling good (or bad) matters. In K. Murnighan (Ed.), Social psychology in organizations: Advances in theory (pp. 63-88). New York, NY: Prentice-Hall. Berger, P. L., & Luckman, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge. Buckingham, M., & Clifton, D. O. (2001). Now, Discover Your Strengths. New York, NY: The Free Press. Capra, E. & Stone, M. (2010). Smart by nature, Schooling for sustainability. Journal of Sustainability, 1 (22-26). Cetegen, D., Veitch, J. A., & Newsham, G. R. (2008). View Size and Office Luminance Effeects on Employee Satisfaction. Proceedings of Balkan Light 2008, Ljubljana, Slovenia, October 7-10, 200 (pp. 245-252). Presented at the Balkan Light 2008, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2008-10-07, Maribor, Slovenia: Lighting Engineering Society of Sloveni. Retrieved from http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/obj/irc/doc/pubs/nrcc50852/nrcc50852.pdf Chawla, L. (2002). Growing up in an urbanizing world. London: UNESCO. Cooperrider, D. L. (1990). Positive Image, Positive Action: The Affirmative Basis of Organizing. In S. Srivastva & D. L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Appreciative management and leadership : the power of positive thought and action in organizations. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/89071651 Cooperrider, D. L., & Sekerka, L. E. (2003). Toward a theory of positive organizational change. In K. M. Cameron, J. E. Dutton,, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship, foundations of a new discipline (pp. 225-240). San Francisco, CA: BerrettKoehler Publishers, Inc. Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (1999). A Positive Revolution in Change: Appreciative Inquiry. In Cooperrider, D.L.,, Sorensen, P. F., Jr., Whitney, D., & Yaeger, T. F. (Eds.), Appreciative inquiry: Trethinking human organizaiton toward a positive theory of change. Champaing, IL: Stipes Publishing Cooperrider, D. L., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. M. (2008). Appreciative Inquiry Handbook. Brunswick: Crown Custom Publishing, Inc. Critchley, B., & Stuelten, H. (2008, July). Starting When We Turn Up: Consulting from a Complex Responsive Process Persepctive. Unpublished manuscript, . Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. (2003). The power of high-quality connections. In K. M. Cameron, J. E. Dutton,, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship, foundations of a new discipline (pp. 263-278). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. Farley, K. M. J., & Veitch, J. A. (2001). A Room with a View: A Review of the Effects of Windows on Work and Well-Being ( No. RC-RR-136). National Research Council of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/obj/irc/doc/pubs/rr/rr136/rr136.pdf Fonseca, J. (2002). Complexity and Innovation in Organizations. London: Routledge. Sustainable Organizing 27 Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology, the Broadenand-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). Positive emotions and upward spirals in organizations. In K. M. Cameron, J. E. Dutton,, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship, foundations of a new discipline (pp. 163-175). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2001). Positive emotions. In T. J. Mayne & G. A. Bonnano (Eds.), Emotion: Current issues and future directions (pp. 123-151). New York, NY: Guildford. George, D. R., & Whitehouse, P. J. (2010). Intergenerational volunteering and quality of life for persons with mild-to-moderate dementia: results from a 5-month intervention study in the United States. Journal Of The American Geriatrics Society, 58(4), 796 - 797. George, J. M. (1991). Leader positive mood and group performance: The case of customer service. Journal of Applied Social Science, 25, 778-794. George, J. M. (1998). Salesperson mood at work: Implications for helping customers. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 18, 23-30. Gioia, D., & Pitre, E. (1990). Multiparadigm Perspectives on Theory Building. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 584-602. Gleick, J. (1987). Chaos: making a new science. New York, NY: Penguin. Goldstein, J. (1999). Emergence as a construct: history and issues. Emergence, 1(1), 49-72. Griffin, D. (2002). The Emergence of Leadership: Linking Self-organization and Ethics. London: Routledge. Griffin, D., & Stacey, R. (2005). Introduction: Leading in a Complex World. Complexity and the Experience of Leading Organizations (pp. 1-16). New York: Routledge. Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention and Treatment, 3(3). Retrieved from http://journals.apa.org/prevention. Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing : positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275-289). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/2002033219 Hart, R. (1996). Forest gardening : cultivating an edible landscape. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. Hartig, T., Mang, M., & Evans, G. (1991). Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environment and Behavior, 23(1), 3-26. Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1993). Emotional contagion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 96-99. Hinrichs, G. (2009). Organic Organizational Design. OD Practitioner, 41(4), 4-11. Holmgren, D. (2002). Permaculture: principles and pathways beyond sustainability. Hepburn, Victoria, Australia: Holmgren Design Services. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/2003446690 Holmgren, D. (2007). Essence of Permaculture: a summary of permaculture concept and principles taken from Permaculture Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability by David Holmgren. Hepburn, Victoria, Australia: Holmgren Design Services. Retrieved from http://www.holmgren.com.au/DLFiles/PDFs/Essence_of_PC_eBook.pdf Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1122-1131. Sustainable Organizing 28 Jacke, D. (2005). Edible forest gardens (Vols. 1-2). White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/2004029745 Kahn, P. H. (1999). The Human Relationship with Nature: Development and Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Kaplan, Rachel, & Kaplan, Stephen. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kaplan, S., & Talbot, J. (1983). Psychological benefits of a wilderness experience. In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Behavior and the natural environment. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/83007285 Katcher, A., Freidmann, E., Beck, A. M., & Lynch, J. J. (1983). Looking, talking and blood pressure: the physiological consequences of interaction with the living environment. In A. Katcher & A. Beck (Eds.), New perspectives on our lives with companion animals. Philadelphia, PA: University of Philadelphia Press. King, K. (2010). Organisational Consulting: at the Edges of Possibility. Faringdon, Oxfordshire, UK: Libri Publishing. Klemmer, C. D., Waliczek, T. M., & Zajicek, J. M. (2005). Growing Minds: The Effect of a School Gardening Program on the Science Achievement of Elementary Students. HorTechnology, 15(3), 448-452. Knippenberg, D. van, & Schippers, M. C. (2007). Work Group Diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 515-41. Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Leather, P., Pygras, M., Beale, D., & Lawrence, C. (1998). Windows in the Workplace: Sunlight, View, and Occupational Stress. Environment and Behavior, 30, 739-762. Lepore, S. J., Mata-Allen, K. A., & Evans, G. W. (1993). Social support lowers cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 518-524. Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving social conflicts; selected papers on group dynamics (Gertrude W. Lewin, ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row. Lewin, R. (1993). Complexity: Life on the Edge of Chaos. London: Phoenix. Lohr, V. I., Pearson-Mims, C. H., & Goodwin, G. K. (1996). Interior Plants May Improve Worker Productivity and Reduce Stress in a Windowless Environment. Journal of Environmental Horticulture, 14(2), 97-100. Losada, M. (1999). The complex dynamics of high performing teams. Mathematical and Computer Modeling, 30, 179-192. Losada, M., & Heaphy, E. (2004). The Role of Positivity and Connectivity in the Performance of Business Teams: A Nonlinear Dynamics Model. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 740765. Louv, R. (2008). Last Child in the Woods - Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Updated and Expanded edition.). Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/2004066034 McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249-266. Mollison, B. C. (1990). Permaculture : a practical guide for a substainable future. Washington, DC: Island Press. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/90032109 Sustainable Organizing 29 Mollison, B. C., & Holmgren, D. (1978). Permaculture 1: a perennial agricultureal system for human settlements. Melbourne, Australia: Transworld Publishers. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/81480438 Mollison, B. C., & Slay, R. M. (1992). Introduction to permaculture. Tyalgum, Australia:: Tagari Publications. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/92982140 Moore, R. C., & Wong, H. H. (1997). Natural learning: creating environments for rediscovering nature’s way of teaching. Berkeley, CA: MIG Communications. Morgan, G. (1998). Images of Organization - The Executive Edition. San Francisco, CA. Nicholson, S. (1971). How to not treat children: The theory of loose parts". Landscape Architecture, 61, 1 (30-34). Orians, G., & Heerwegen, J. (1992). Evolved responses to landscapes. In J. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted Mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://lccn.loc.gov/91025307 Peter, M., & Robinson, V. (1984). The Origins and Status of Action Research. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 20(2), 113-124. Pfeffer, J. (2009). Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor ( No. 2017). Research Paper Series. Stanford, CA: Stanford Graduate School of Business, Stanford University. Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. Quinn, R. E. (2000). Change the world: How ordinary people can achieve extraordinary results. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Roszak, T. (2001) The voice of the earth - An exploration of Ecopshychology. Grand Rapids: Michigan: Phanes Press Inc. Originally published: New York: Simon Schuster, 1992. Seel, R. (2006). Emergence in Organizations. New Paradigm Consulting. Retrieved May 15, 2011, from http://doingbetterthings.pbworks.com/f/RICHARD+SEEL+Emergence+in+Organisations .pdf Shaw, P. (2002). Changing Conversations in Organizations: A Complexity Approach to Change (Complexity and Emergence in Organizations). New York, NY: Routledge. Stacey, R. (2001). Complex Responsive Processes in Organizations. London: Routledge. Stacey, R. (2002). Organizations as Complex Responsive Processes of Relating. Journal of Innovative Management, 8(2), 27-39. Stacey, R. (2005). Experiencing Emergence in Organization. New York, NY: Routledge. Stacey, R. (2010). Complexity and Organizational Reality: Uncertainty and the Need to Rethink Management after the Collapse of Investment Capitalism. London: Routledge. Stacey, R., Griffin, D., & Shaw, P. (2000). Complexity and Management: Fad or Radical Challenge to Systems Thinking? London: Routledge. Staw, B. M., & Barsade, S. G. (1993). Affect and managerial performance: A test of the saddlerbut-wiser vs. happier-and-smarter hypotheses. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 304331. Staw, B. M., Sutton, R. I., & Pellod, L. H. (1994). Employee positive emotion and favorable outcomes at the workplace. Organizational Science, 5, 51-71. Streatfield, P. (2001). The Paradox of Control in Organizations. London: Routledge. Taylor, F. A. (1911). Principles of Scientific Management. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Sustainable Organizing 30 Taylor, S. E., Dickerson, S. S., & Klein, L. C. (2002). Toward a biology of social support. In C. R. Snyder & S. L. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 556-572). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Trist, E. L. (1983). Referent organizations and the development of inter-organizational domains. Human Relations, 36, 269-284. Trist, E. L., & Bamforth, K. W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the Longwall method of Coal Getting. Human Relations, 4, 3-38. Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View Through a Window May Influence Recovery From Surgery. Science, 224, 42-421. Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201-230. Waldrop, M. M. (1992). Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Simon & Shuster. Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational Organizations as Loosely Coupled Systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1-19. Wells, N., & Evans, G. (2003). Nearby nature: a buffer of life stress among rural children. Environment and behaviors, 35, 311. Wheatley, M. (2007). Finding Our Way: Leadership for an Uncertain Time. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. Whitehouse, P. J. (2011, May 9). MPOD Forest Garden Team - Update.