Martha Blake `The Psychology of Sacrifice`

advertisement

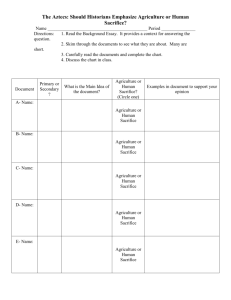

1 Martha Blake ‘The Psychology of Sacrifice’ In the spring of 2001, I began sorting through information I had been collecting on the practice of sacrifice in the early hunting and agrarian religions. I had read there was a difference in their practices and I wanted to describe the dichotomy. My interest was academic and intellectual. Then the events of September 11, 2001 graphically brought the word "sacrifice" to our ears each day as newscasters described the various ways people from all over the world had given their lives in the drama of the World Trade Center. In October, I had an archetypal sacrifice dream harkening back to the Bronze Age. My curiosity was now grounded in profound emotional experience and had shifted to the much larger topic of the nature of human sacrifice in general. I longed to know why individuals and cultures engage in sacrifice, why there are so many forms of sacrifice, and where in the human psyche the desire to sacrifice originates. This paper documents an exploration into theories of the origins -- what might be called the phylogeny of sacrifice, explores the additions to consciousness of several religions and cultures-what might be called the ontogeny of sacrifice, and proposes the psychic processes that may be at work as humans sacrifice. THEORIES OF SACRIFICE According to E.O. James, the history of ritual is the history of religion, and the importance of sacrifice to the human psyche is evidenced by its ability to survive even when it is reinterpreted into metaphysical and ethical concepts. [i] James held that in order to understand a practice as fundamental as sacrifice, one had to approach it anthropologically, historically and psychologically. He believed, as many others do, that in the broadest sense, mankind performed sacrifice as a purifying and life-giving process to remove the taint of evil and assure a desired outcome. Ancient practitioners ritually removed or wiped away pollution contracted involuntarily and unwittingly. [ii] To the primitive mind, good and evil, life and death are in the nature of materialistic qualities capable of transference or expulsion by quasi-mechanical operations. Misfortune and disaster demand concrete atonement in order to remove evil and restore right order between man and the natural order. Failure of crops, calamities, plagues and diseases are attributed to ritual defilement that is removable by life-giving substances such as blood and water. Sacrifice then is the normal means of transferring life and power to mortal deities to keep them vigorous and beneficent. [iii] The word “sacrifice” and the word “sacred” both derive from the Latin, “sacrificium” meaning “to set apart from the profane, to make sacred” although in colloquial usage, it has come to have many different connotations. Sacrificial acts are highly differentiated-- there are many motivations for and forms of sacrifice, although it always entails offering life in one form or another. [iv] Most theories of sacrifice focus on a conscious action behind an original rite, a kind of “if-then” causal thinking. If the community sacrifices, so the thinking goes, then the gods will respond. Here is how some anthropologists have described approaching the numinosum via sacrifice. (Emphasis mine.) o o o o o o Tylor: Sacrifice is a gift to the soul of a person, object, or personified cause. Robertson-Smith: Sacrifices is a communion that establishes or re-establishes kinship between the worshiper and his god. Frazer: Sacrifice is a form of imitative magic. Westermarck: Sacrifice is a substitution of the victim for the worshiper who has incurred the wrath of the gods. Hubert and Mauss: Sacrifice offers an intermediary between the worshiper and the dangerous forces of the supernatural world. Loisy: Sacrifice is a combination of the ritual gift and the magical and symbolic rite of destruction to acquire or eliminate something.[v] 2 FORMS OF SACRIFICE A survey of the literature reveals that sacrifice takes on many forms depending on the cultural application and that the process varies as well. What follows is a summary of the forms of sacrifice: Robertson Smith hypothesized that sacrifice functions to commune between members of a group and between the group and their god. Two forms of sacrifice have emerged over time: o o Expiatory - piaculum to re-establish a broken covenant Gift- honorary[vi] James, however examined the way the word “sacrifice” is used and identified six meanings in common usage: Maintain sacred order- gods fulfill beneficent functions on earth. Gifts as presents or tributes paid by creatures to Creator, an honorarium. Atone for wrongdoing-piacular offering of life in expiation for sin. Voluntary self-destruction or surrender-self-sacrifice. Philanthropic endeavor involving loss. Disposal of an article at a greatly reduced value.[vii] The Biblical book of Leviticus reduces all sacrifices to four elemental forms that were interwoven in practice: o o o o o o Olah- offerings to the divinity Hattat-expiation of sins committed in ignorance of the Lordâs commandments Shelamin-communion, thanksgiving, vows of alliance Minha- presentation of vegetable matter[viii] Hubert and Mauss reviewed German culture and identify three overlapping reasons for sacrifice: o o o o Expiatory (Schnopfer) Thanksgiving (Dankopfer) Requests (Bittopfer)[ix] Hindu texts differentiate sacrifices by their frequency: o o o Regular- periodical (nityani), daily, new and full moons, seasonal and pastoral festivals, first fruits. o Occasional- sacramental (samskara), domestic, rites of passage, solemn, anointing a king, religious and civil events, and votives. When Hubert and Mauss examined what happened to the substance of the sacrifice, they described two forms. Sacrifice is reserved for the latter form: o A votive, whose nature does not change as it is assigned to the service of the god, e.g. first fruits left at the temple. o A living thing that is destroyed in the offering up process, e.g. a victim that is killed or grains that are crushed. [x] Herbert and Mauss describe sacrifices as a request, personal, or objective, -or a combination of these elements. o Personal sacrifices: o o o Begin and end with the sacrificer-revolve around the sacrificer. Regenerate the sacrificer-eradicate evil, regain state of grace, transfer divine power, grant salvation, infuse the god, transform personality, proffer rebirth. May extend into the future- result in a change of name, transfer the forces of immortality to the soul.[xi] 3 Objective sacrifices: o o o Benefit something other than the sacrificer-revolve around another object and only secondarily affect the sacrificer. Focus more on the creation of spirit, e.g. guardian spirit. Modify the sacrifice itself so that the attributes of the sacrifice (such as color) may be transferred to the object.[xii] Sacrifices of request: o o o o Bring about certain special effects defined by the rite. May release the promiser. May bind the god by a contract. Dictate the importance of the sacrificial victim.[xiii] Sacrifices may combine elements of all the above in complex rituals. An agrarian sacrifice can involve confession, purification, death of the victim, communion with the divine, and a resurrection as it: o o o o o o Reawakens the life principle in a field dormant after winter. Fertilizes the field. Allows the life principle to enter what will be grown there. Preserves the life force in the field after the harvest. Desacrilizes the harvest so that it may be eaten. Redeems those who have worked in the field, their offspring, and those who have made the sacrifice.[xiv] Many social customs are linked to sacrifice: o o o o o o o Contracts Redemption Penalties Gifts Abnegation (to deny, renounce oneself) Immortality Morality[xv] Therefore it may be said that the central conception underlying the institution of sacrifice is the giving of life to promote and conserve life. Offering life to preserve life is the beginning of substitution and propitiation, which in many of the higher religions has evolved into a lofty ethical significance. [xvi] A description of one sacrifice parallels the core elements of all sacrifices: The victim is brought to the place of sacrifice and there are performed in succession the four acts which compose the sacrificial drama: presentation, consecration, invocation, and immolation. [xvii] o o Originally, men and animals were perceived (archaic consciousness) in kinship with each other. A totem animal was sacrificed, distributed and eaten. The totem animal’s blood contained the holy life force shared by man. When animals were domesticated and the kinship between man and animal was forgotten (went into the unconscious) a domestic animal became the routine sacrifice. When the totem or piaculum was sacrificed non-routinely, it was perceived as so sacred that it was either completely destroyed or only offered to the priests to eat. 4 EVOLUTION OF SACRIFICE In Totem and Taboo, Freud added to what the anthropologists had learned about the conscious act of sacrifice. Freud saw in the sacrifice of a totem animal an unconscious repetition of a primeval crime-a repetition and commemoration, or at least an unconscious desire for parricide that each individual has inherited. Freud’s work on totems suggests that behind every act of sacrifice are both conscious and unconscious aspects. In 1956, in a letter to Mrs. Kotschnig, Jung noted that “the religious spirit of the West is characterized by a change of God’s image in the course of ages.” [xviii] Jung made another important contribution to understanding the nature of sacrifice when he noted that the nature of sacrifice may have evolved along with God’s image. In early hunting societies comprised of small groups of people, the hunted animal was the sacrifice. Life, death, and blood were consecrated in the act of killing one animal at a time, incrementally. The next sacrifice was as near as the next hunt. In agricultural societies, members performed sacrifices to assure the progression of the seasons and the growth of crops. If blood could keep man and animal alive, then it had life-giving qualities that could be brought to bear on the weather and the soil. Human blood in particular represented human vitality or life essence. If kings were perceived as something more than human-either extra-human or divine-then the blood of kings contained still more life essence. Sacrificing a king at the peak of vitality maximized the lifequality of the blood offering. Later as cultures adopted solar religions, members of the community were sacrificed instead of the king.[xix] In agrarian societies, a sacrifice covered an entire growing season or reign and extended to a larger number of settled people. The stakes were higher and the sacrifice was often dearer-a human life. Even though pure totemism exists in only a few remaining cultures, Robertson Smith postulated totemic sacrifice as an evolution of conscious and unconscious elements reaffirming the relationship between god and man: Robertson Smith claimed that the basic rite in ancient and primitive religions is the sacrificium.[xx] (My parens.): Eventually, rare human sacrifice replaced animal sacrifice. Humans became the only way to exchange common blood between man and god, the piaculum sacrifice. Animals had been demoted to the level of gift sacrifice from the individual owner to the god. At the end of the ritual, just as a scapegoat, the sacrificial animal carried away the impurities of its owner.[xxi] E.B. Tylor also formulated an origin and progression for all forms of sacrifice. Although his theory does not address the means of sacrifice, it did focus on the importance of sacrifice to the self. o Originally sacrifice was a gift made by the primitive to supernatural beings with whom he needed to ingratiate himself. o Then the gods grew greater and more removed. Sacrificial rites developed to spiritualize objects that would reach the spiritualized gods. o Eventually, the sacrificer expected no return, just paid homage. o Later, the sacrificial rite involved abnegation and renunciation-the symbolic sacrifice of ones self. [xxii] In the following chart, I have attempted to summarize the contributions to consciousness-the ontongeny-- that have evolved with the practice of sacrifice by of each religion or culture. I propose that different levels of consciousness may coexist on the globe at any one period in history, including our own. o 5 CULTURE RELIGION Babylonians Assyrians Egyptians Crete Greeks EXAMPLE FROM RITUAL OR MYTH USE Innini, the Great Mother, identified with Antu the goddess of war. Herdsmen made offerings to Ninamasazagga, the shepherd of the sacred goats of Enlil, to preserve them and their flocks. Marduk combats Tiamat, Chaos. Attribute sickness and bad luck to unwitting commitment of an error. “I know not the sin which I have done.”[xxiii] Legend of Adapa. Ishtar, mother and wife of Dumuzu pours water from the spring of life that she has fetched from hell over the sacrificed corpse of Dumuzu. [xxv] Osiris-dispersal of corpse and tree growing from coffin. Mithras rides on the bull he is going to sacrifice. Legend of Charila at Delphi. During famine, Charila asks the king for food. He beats her and drives her away. She hangs herself. [xxvi] Consecrated sheaf takes the form of an animal or man: Life of the vine becomes Dionysus/goat, life of the corn becomes Demeter/ pig.[xxvii] Constellation Virgo is Erigone, an agrarian goddess who hanged herself. Artemis, Hecate and Helen also hanged.[xxix] Iodoma of Iton was the priestess of Athena Itonia; Aglaurous of Athens was the priest of Athena. Ea commands his son Marduk to take the king a scapegoat to take on his curse. ADDITION TO COLLECTIVE CONSCIOUSNESS Humans can interact with the gods to mediate circumstances. Explain creation as death of one god and survival of another usually as a rite of spring. [xxiv] Imitates the rites of agrarian feasts that use sprinkled water to restore the life of a field. The vanquished is as divine as the conqueror; opponents are of a single spirit. Ritual sacrifice related to theme of death and resurrection of a god. Sprinkling water related to new life. Assures flooding of the Nile, fertility and harvest. Dualism-opposing forces of good and evil. Humans can intervene for good. God undergoes ongoing periodic sacrifice. Sacrifice related to the mutilation, death, and resurrection of an agrarian principle; homogeneity of victim and god. Grain and wine as soul. [xxviii]Spirit becomes detached from what sustained it. A god already formed both acts and suffers in the sacrifice. Explains the treatment of beating, drying and seeding the corn. Sacrifice appears to perpetually repeat and commemorate an original sacrifice. Victims exalted, rendering them directly divine.[xxx] [xxxiii] God appears to escape death. Sacrifice to the god develops parallel with sacrifice of the god. [xxxi] Atonement for the king as representative of the people. Sacrificed goats when new house erected, fresh ground broken, trees cut down, well dug, or first fruit of harvest gathered. Abel sacrificed a lamb. Later substituted butter and henna handprints. Firstborns[xxxiv] Applied in periods of acute drought when populations stressed. Protection against jinn, ghuls, afrits that assumed animal forms. A symbolic handprint can substitute for a sacrificial animal. Evolved from offering first harvest. Offered humans to the moon during a spring festival; Abraham and Issac (Genesis 22: 1-19.)”Even their sons and daughters they have burnt in the fire to their gods.” [xxxv] Dual conception of getting rid of evil to secure good, of expelling death to gain life. Propitiation. Hebrews: Post exodus Lord tells Aaron how to sacrifice a scapegoat. [xxxviii] Atonement for the people of Israel. “Kipper” to cover. (James 198) Day of Atonement; Passover. Judiasm after 70 AD Sacrificing ceased after the destruction of the Temple. Greeks Agrarian sacrifice rituals of grain and wine probably preceded myths of Demeter and Dionysis. References remain in Orthodox prayer book, although references eliminated from Reform practices. Athenian soothsayer Euthyphro maintained piety required prayer and sacrifices. Socrates held sacrifice is giving and prayer is asking. Survival may require offering that which is most dear in order for the community to survive. Consecration of the victim or the offering serves as an intermediary, an open channel for energies to flow between the sacrificer and the divinity.[xxxvii] Substituting a ram for Isaac reinstituted animal sacrifice instead of firstborns. Blood makes atonement for ritual uncleanliness by reason of “nephesh” or soul substance it contains. Death met by a barrier of life at the doorway. [xxxix] Prayer takes the place of sacrifice. Sumerians Doubles the divine- priest is an incarnation of god and victim. “Kippuru” to tun away or remove. [xxxii] Early Semites Ancient Palestine [xxxvi] Sacrifice as a trade -an economic transaction.[xl] 6 CULTURE RELIGION Hindu Brahmins Hindu Brahmins Indonesia and Pacific Nahuas and Mayans Aztecs EXAMPLE FROM RITUAL OR MYTH USE King makes offering to fire-god, the offering is the fire-god, the king becomes the fire-god. But the general is the firegod, so the king becomes one with the general, so the general becomes the kingâs faithful follower. Brahmins interpolate Soma the god with soma the plant that is pressed and killed in spring. [xliii] Tribes viewed heads as rich in soulsubstance. Headhunting associated with well being of crops and cattle. Vaporous soul contains vitalizing principle and acts like manure when spread over fields. When grain is eaten, its life-giving power is passed into the blood, then to seminal fluid. Nomadic people who introduced human sacrifice into Central America after they adopted a settled life and borrowed agricultural cults from the Mayans. [xlv] Fertility depended on extraction of human hearts to nourish and sustain the sun god Ipalnemohuani. Victims skins worn by men personating the god to show that the earth-god had put on a new cloak. Prisoner disguised as divinity, hosted for a year then sacrificed. Successor immediately invested in office. Women and girls sacrificed at other months in the growing season. [xlvi] “Rita” is universal --cosmic order, ritual sacrifice and moral law. Later replaced by Karma, the doctrine of the deed and Atman, or world-soul.[xli] Soma is perceived disguised as evil which is then killed. The desire to imbibe the attributes and qualities of the victim led to cannibalism and to surrogate cannibalism-e.g. blood combined with maize paste. Transform the Aztec warrior god Uitzilopochtli into a solar divinity. Tradition told of four previous suns that had been destroyed at the end of previous world-epochs therefore justified the high cost of sacrifices in 18 of 20 calendar periods. Vegetation cults had a military character reminiscent of the Great Goddess. Purpose was promotion of the life-principle of cereal crops. Victims outside the group obtained by aggressive warfare.[xlvii] When grains removed from maize cobs, sacrifices made to maize images where sun descended. ADDITION TO COLLECTIVE CONSCIOUSNESS The god obtained heaven. The sacrificer is the god. Prajapati at his own sacrifice.[xlii] God is released upon the death of the plant and spread to live throughout the world Cannibalism and sacrifice involved giving and receiving of soulsubstance. [xliv] Stresses on agricultural food sources caused by settling of nomads attributed to gods who required constant appeasement. Calendar reflected a ceremonial cosmic order as a religious system rather than a dating system. Sacrifice linked to war. Incas Sacrifices offered to maintain the vigor of the sun-god. [xlviii] North American Indians Persia: Zoroastrianism Iroquois, Pawnee, Natchez, Pueblostraces of sun and war god sacrifices.[l] Combinations of hunter and agrarian practices. Hunter ethic has survived more in the popular culture. Zarathustra brings the life of his own body, choices of good thought, action and speech unto Mazda. [li] Sacrifice never reached cult status, performed mostly by individuals at certain times of the year. Yin and yang, positive and negative principles, responsible for seasons. First determined effort against the institution of sacrifice. Reverted after Zoroasterâs death. [lii] Atonement by good deeds counteracts the evil committed by the individual. [liii] Worship to secure health and wealth banish famine and barrenness.[lv] Accessible personal deity permanently united to man. His personal sacrifice is periodically reenacted. Man participates in a bloodless renewal and communicates with His transubstantiated form via the Eucharist .God is transformed. Plant and animal sacrifice conflicted with a highly spiritual conception of God. Sacrifice (yanna) is an offering of the self. [liv] [xlix] Buddhism Hinduism: Confucianism Christianity Catholicism Christ sacrificed his life so that others will not need to. Christ symbolized by Paschal Lamb, victim of agrarian or pastoral sacrifice. [lvii] Redemptive sacrifice of the god is perpetuated in the daily Mass. Moral law of justice and ethical rightness. [lvi] One sacrifice 2000 years ago interpenetrates the Christ-quality in accepting material souls forever. [lviii] God sacrifices Himself- Christ as sacrificer and sacrificed. Priest becomes Christ. Man consumes the God in the form of a sacred meal. [lix] Protestantism St. Paul “I beseech you·that you present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God.” [lx] Purely subjective offering of a pure heart, human vitality, and vocal thanksgiving connected with symbols of the death of Christ. [lxi] God sacrifices Himself for man who commemorates the event in remembrance of Him. 7 CULTURE RELIGION Islam Modern Arab youth EXAMPLE FROM RITUAL OR MYTH USE Sacrifice has little place. Sheep offered at end of Haj; served guests at feast meals. Suicide bomber ego ideal. James states that when sacrifice ceases to operate, the associated religion tends to disintegrate. Spilling blood continues the contact with ancestors who protect the clan against invisible forces. ADDITION TO COLLECTIVE CONSCIOUSNESS Lack of emphasis on sacrifice may explain why older Arab traditions filter into fundamental Islamic beliefs. Self sacrifice for community as an act of war. THE PSYCHOLOGY OF SACRIFICE Psychological explanations examine the conscious and unconscious motivations behind the religious ritual-- a desire to restore and maintain a constructive relationship, a balance of life, leads mankind to sacrifice. James stated that if a pattern of relationship is broken or at risk of being broken, something must be done to “atone for or cover or wipe out the offense to re-establish the vital union upon which the welfare of the individual and the group” depends. [lxii] If the breach in the relationship was due to the nature of the god, then “suitable offerings had to be made to secure the continuation of divine benevolence and to set up a barrier against evil.” But if the breach in the relationship was due to the nature of mankind, then the evil had to be “purged and removed by mechanical means such as washings, confessions, offerings of propitiatory value, or transference of the sin to some animal or human victim.” [lxiii] Every sacrifice involves a consecration-a passing from the common into the religious domain. But there are different kinds of consecration related to describing for whose sake the sacrifice is performed-the object of the sacrifice. • Limited - a specific man or thing-king, house, well. • Social--passing to others -sacrificed and sacrificer- individual or group-king and subjects, house and dwellers, well and drinkers. [lxiv] Limited sacrifices accrue psychological benefits to the few. Social sacrifices accrue benefits to the community or society. In Ego and Archetype, Edward Edinger proposed four egoic situations depending on who performs the sacrifice and to whom the benefit accrues:[lxv] SACRIFICE God sacrifices man for God God sacrifices God for man Man sacrifices God for man Man sacrifices man for man and God MOVEMENT Divine realm augmented at expense of human From divine to human From divine to human From transpersonal to conscious ego IMPLICATION Ego too full and transpersonal world too empty. Emptiness of ego requires sustaining influx from transpersonal, collective unconscious. Desacrilization; reluctant relinquishing of old modes of being. A condition requiring an increase in conscious autonomy. Hypothetical ideal. Sacrifice of the ego by the ego for egoâs own development and fulfillment of transpersonal destiny. Motivated by conscious cooperation with urge to individuation rather than unconscious archetypal compulsion.[lxvi] Edinger’s model is consistent with Hubert and Mauss who propose a religious definition with psychological overtones: “Sacrifice is a religious act which, through the consecration of a victim, modifies the condition of the moral person who accomplishes it or that of certain objects with which he is concerned. A personal sacrifice directly affects the personality of the sacrificer. [lxvii] Jung held that religious rites and symbols have developed everywhere the same way and out of the same conditions of human nature. In “Transformation Symbolism in the Mass,” Jung wrote, “The act of making a sacrifice consists in the first place in giving something that belongs to me.” [lxviii] Mine-ness reflects an unconscious identity of object with my ego. If a sacrifice is a true sacrifice, 8 the object must be given as if it were being destroyed. Any claim of ego to the object in the future is foregone. The Deity must not be bribed. The sacrificer must be conscious of his identity with the gift and have some awareness of how much of himself he is giving up as he sacrifices the gift. With each sacrifice, there are claims attached, “the more so, the less we know of them.”[lxix] If one gives and expects nothing in return, one experiences a loss. A sacrifice is meant to be like a loss, the ego relinquishes any claim on the object. Jung held that if you can give yourself, then it is an indication that you possess yourself. Therefore anyone who can sacrifice himself and forgo his claim to himself, must be conscious of having a claim -possess considerable self-knowledge. This means the ego can be subsumed as an object under the supraordinate authority of a personality that is emerging into consciousness from the unconscious. Jung called this process “individuation.” According to Jung, the first step in a resolution of the conflict between conscious and unconscious is to become aware of it. An act of self-consciousness is inherent in each act of self-sacrifice. When an ego becomes conscious of its claim to itself, the self causes the ego to relinquish the claim. [lxx] Jung states that renouncing a claim in consideration of a general moral principle is a superego function. I propose that renouncing a claim in consideration of a powerful individual principle, even in the face of some resistance, is a function of the ego ideal. Peter Blos, in his book entitled The Adolescent Passage poses that The ego ideal spans an orbit that extends from primary narcissism to the Îcategorical imperative,â from the most primitive form of psychic life to the highest level of manâs achievements. Thus the fright of the finitude of time, of death itself, is rendered nonexistent, as it once was in the state of primary narcissism. ·thus propelling man toward incredible feats of creativity, heroism, sacrifice, and selflessness. One dies for oneâs ego ideal rather than let it die.[lxxi] As Jung notes, none of this is without considerable suffering. An observing consciousness feels tortured during any process of transformation, and sacrifice is a process of transformation. CONCLUSION For the purpose of this paper, there has been no attempt to distinguish between observing a sacrifice, offering the sacrifice, and being the object that is sacrificed. Jung stated that every sacrifice is to a greater or lesser degree a self-sacrifice. To participate in an act of sacrifice at any level requires relinquishing a claim of ego, and it is the self that effects that relinquishment. The self is the sacrificer. The ego is the sacrificed gift-the human sacrifice. I propose that on the collective level it may be the Self that is the sacrificer, and that the egos of all participants are altered by the sacrificial gift. Jung stated that the divine sacrifice corresponds to the manifestation of the archetype of the “ root of almost all known conceptions of God. It is always a drama, whether in heaven, on earth, or in hell.[lxxii] Human sacrifice, on the collective level, is visible in attitudes toward war whenever a nation or leaders command allegiance as passionate as any religion. Eric Fromm compared the slaughter of WWI to child sacrifice. [lxxiii] Nigel Davies saw the Kamikaze pilots arising from the principles of the Shinto religion. Orthodox Islam pays little attention to the issue of sacrifice, although by ancient tradition, each pilgrim to Mecca sacrifices a lamb and feast meals include a lamb or goat.[lxxiv] The youths willing to sacrifice themselves in the name of fundamental Islam are in actuality responding to ancient Arab myths resonating in their cultural unconscious öthat spilling blood continues a contact with ancestors who protect the clan from invisible forces. Hubert and Mauss maintain that for sacrifice to be truly justified, two conditions are necessary: There must exist outside the sacrificer things which cause him to go outside himself, and to which he owes sacrifices. These things must be close to him so that he can enter into relationship with them, obtain strength and assurance, and obtain the benefits he expects from them. Social relationships satisfy both of these conditions better than anything else. The collective force of mental and moral energies in fact sustains sacrifice. The abnegation required in the act of sacrifice reminds individuals of these collective forces they have conferred on each other.[lxxv] 9 Suicide bombing as an act of individual sacrifice to further the cause of the tribe, clearly meets both of Hubert and Maussâ social conditions and may meet Edingerâs forth condition of the ego. Suicide bombing is therefore is likely to continue as a form of self-sacrifice acceptable to large segments of global society, especially when the families are compensated and the bombers are hailed as martyrs. Pathological behaviors can be acquired through modeling. Antisocial behaviors benefit the self at great expense to others. Prosocial behaviors benefit others, usually at little reward or cost to the subject. Antisocial behaviors probably develop more easily and are more resistant to extinction whereas prosocial behaviors easily fail to take root. Reinforcement and shaping of positive and adaptive behaviors is thus as important as the extinction of maladaptive behaviors.[lxxvi] Suicide bombing as an act of sacrifice contains both prosocial and antisocial elements that may make it especially appealing to the young. This paper has been a personal exploration into the phylogeny and ontogeny of sacrifice. Each period in history, each religion and culture, has added to the collective consciousness of sacrifice. At the same time, both the archetype of sacrifice and the sum of human experience remain in the collective unconscious to emerge again at any time. The challenge for individual citizens in a global society is to hold the several versions of sacrifice that may be operating simultaneously within current events or as cultures clash. The important thing is this: To be able at any moment to sacrifice what we are for what we could become. [lxxvii] ________________________________ 10 ENDNOTES [i] James, 289. [ii] James 186. [iii] James 184-185. [iv] Encyclopedia Britannica, Volume 16, p 128. [v] Summarized by Money-Kyrle, 259. [vi] Hubert and Mauss, 3. [vii] James 289-290. [viii] Hubert and Mauss, 16. [ix] Hubert and Mauss, 14. [x] Hubert and Mauss, 12. [xi] Hubert and Mauss, 62-64. [xii] Hubert and Mauss, 64-65. [xiii] Hubert and Mauss, 65-66. [xiv] Hubert and Mauss, 66-69. [xv] Hubert and Mauss, 103. [xvi] James 289, 196. [xvii] Eliade, 53. [xviii] Jung., Letters, 1956, 315. [xix] James, 99. [xx] Evans-Pritchard, in Hubert and Mauss, vii. [xxi] Hubert and Mauss, 3-5. [xxii] Hubert and Mauss, 2. [xxiii] Langdon in James, 193; “Kippuru” to remove or wipe away. James, 198. [xxiv] Hubert and Mauss, 85-86. [xxv] Hubert and Mauss, 83. [xxvi] Hubert and Mauss, 84. [xxvii] Hubert and Mauss, 78-79. [xxviii] Jung, Op. cit, 254. [xxix] Humbert and Mauss, 87. [xxx] Hubert and Mauss, 79. [xxxi] Hubert and Mauss, 90. [xxxii] Thompson in James 197. [xxxiii] James 198-199. [xxxiv] Frazer in James 189. [xxxv] Deuteronomy 12:31. [xxxvi] James 192. [xxxvii] Hubert and Mauss, 11. [xxxviii] Leviticus 16. [xxxix] James 190. [xl] James 287. [xli] James 276. http://www.marthablake.com/sacrifice.html [xlii] Sat. Br., vii2;iii, 2,2,4 in James 277. [xliii] Hubert and Mauss, 90-91. [xliv] James 108-112. [xlv] James 84. [xlvi] James 85-88. [xlvii] James 85- 92. [xlviii] James 94. [xlix] James 95-96. [l] James 94. [li] James 279. [lii] Moulton in James 279. [liii] James 282-283. [liv] James 282-283. [lv] James 286. [lvi] James 286. [lvii] Hubert and Mauss, 81. [lviii] James 287. [lix] Jung, Op Cit, para 403. [lx] James 279. [lxi] James 289. [lxii] James 187. [lxiii] James, 186-187. [lxiv] Modified from Hubert and Mauss, 9-10. [lxv] Edinger, 244-245. [lxvi] Edinger cited mythological examples of Prometheusâ theft of fire and the original sin of Adam and Eve. [lxvii] Hubert and Mauss, 13. [lxviii] Jung, Psychology and Religion: East and West, para 389. [lxix] Jung, Op cit, para 390. [lxx] Jung, Op cit, para 392. [lxxi] Blos, p 368-369 [lxxii] Jung, Op cit, para 402. [lxxiii] Fromm in Davis, 284. [lxxiv] Encyclopedia Britannica, Volume 16, 135. [lxxv] Hubert and Mauss, 101-102. [lxxvi] Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology, 41. [lxxvii] Charles DuBois