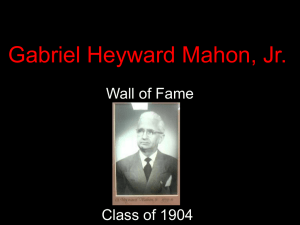

1 West - "Hot Municipal Contest" "A Hot Municipal Contest": Politics

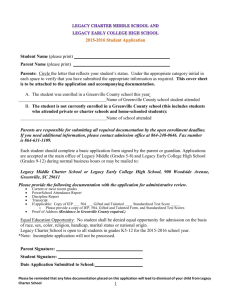

advertisement