Collins-v-SS-for-Business-Innovation-and-Skills-Hand

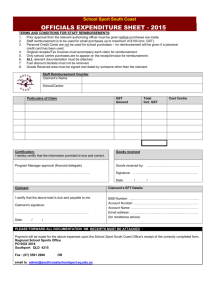

advertisement

Neutral Citation Number: [2014] EWCA Civ 717 Case No: B3/2013/1384 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION MR JUSTICE NICOL HQ12XO1990 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 23/05/2014 Before : LORD JUSTICE JACKSON LORD JUSTICE LEWISON and LADY JUSTICE MACUR --------------------Between : GEORGE WALTER COLLINS - and (1) THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS INNOVATION AND SKILLS (2) STENA LINE IRISH SEA FERRIES LIMITED Appellant Respondents ----------------------------------------Mr Simon Kilvington (instructed by Corries Solicitors Ltd) for the Appellant Mr Colin Nixon (instructed by DAC Beachcroft LLP) for the First Respondent Mr David Platt QC and Miss Claire Toogood (instructed by Berrymans Lace Mawer LLP) for the Second Respondent Hearing date: 9th May 2014 --------------------- Approved Judgment Double-click to enter the short title Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Lord Justice Jackson: 1. This judgment is in seven parts, namely: Part 1. Introduction paragraphs 2 to 9 Part 2. The facts paragraphs 10 to 19 Part 3. The present proceedings paragraphs 20 to 24 Part 4. The appeal to the Court of Appeal paragraphs 25 to 28 Part 5. The date of constructive knowledge paragraphs 29 to 51 Part 6. The application of section 33 of the Limitation Act 1980 paragraphs 52 to 76 Part 7. Executive summary and conclusion paragraphs 77 to 79 Part 1. Introduction 2. This is an appeal against a decision of Mr Justice Nicol that the claimant’s personal injury claim is statute barred. All the breaches of duty which the claimant alleges occurred between 1947 and 1967. The two issues in this appeal are the date of constructive knowledge under section 14 of the Limitation Act 1980 and whether the judge ought to have extended time under section 33. 3. The principal question of law in this appeal is whether and how the judge was entitled to take into account the delay occurring between 1947 and mid-2003, which was the date of constructive knowledge on the judge’s analysis. Counsel on both sides described this question as an issue of seminal importance in relation to long tail industrial disease claims. This question has been addressed in earlier authorities, but perhaps not as fully as one might expect. 4. The claimant, George Collins, is a former dock worker. His solicitors are Corries, a firm specialising in personal injury claims. The first defendant, the Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, is responsible for the liabilities of the National Dock Labour Board (“NDLB”), a body which no longer exists. The second defendant is a stevedoring company which operated at London Docks between 1947 and 1967. It was then called Scruttons Ltd (“Scruttons”). 5. I shall refer to the Limitation Act 1980 as “the Limitation Act” or “LA”. 6. Section 11 (4) (b) of the Limitation Act provides that a personal injury action shall not be brought more than three years after the date of knowledge. 7. Section 14 of the Limitation Act provides: “Definition of date of knowledge for purposes of sections 11 and 12. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title (1) Subject to subsection (1A) below, in sections 11 and 12 of this Act references to a person’s date of knowledge are references to the date on which he first had knowledge of the following facts— (a) that the injury in question was significant; and (b) that the injury was attributable in whole or in part to the act or omission which is alleged to constitute negligence, nuisance or breach of duty; and (c) the identity of the defendant; and (d) if it is alleged that the act or omission was that of a person other than the defendant, the identity of that person and the additional facts supporting the bringing of an action against the defendant; and knowledge that any acts or omissions did or did not, as a matter of law, involve negligence, nuisance or breach of duty is irrelevant. …. (3) For the purposes of this section a person’s knowledge includes knowledge which he might reasonably have been expected to acquire — (a) from facts observable or ascertainable by him; or (b) from facts ascertainable by him with the help of medical or other appropriate expert advice which it is reasonable for him to seek; but a person shall not be fixed under this subsection with knowledge of a fact ascertainable only with the help of expert advice so long as he has taken all reasonable steps to obtain (and, where appropriate, to act on) that advice.” I refer to knowledge which a person ought to have acquired under section 14 (3) as “constructive knowledge”. 8. Section 33 of the Limitation Act provides: “Discretionary exclusion of time limit for actions in respect of personal injuries or death. (1) If it appears to the court that it would be equitable to allow an action to proceed having regard to the degree to which— Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title (a) the provisions of section 11 or 11A or 12 of this Act prejudice the plaintiff or any person whom he represents; and (b) any decision of the court under this subsection would prejudice the defendant or any person whom he represents; the court may direct that those provisions shall not apply to the action, or shall not apply to any specified cause of action to which the action relates. …. (3) In acting under this section the court shall have regard to all the circumstances of the case and in particular to— (a) the length of, and the reasons for, the delay on the part of the plaintiff; (b) the extent to which, having regard to the delay, the evidence adduced or likely to be adduced by the plaintiff or the defendant is or is likely to be less cogent than if the action had been brought within the time allowed by section 11 by section 11A or (as the case may be) by section 12; (c) the conduct of the defendant after the cause of action arose, including the extent (if any) to which he responded to requests reasonably made by the plaintiff for information or inspection for the purpose of ascertaining facts which were or might be relevant to the plaintiff’s cause of action against the defendant; (d) the duration of any disability of the plaintiff arising after the date of the accrual of the cause of action; (e) the extent to which the plaintiff acted promptly and reasonably once he knew whether or not the act or omission of the defendant, to which the injury was attributable, might be capable at that time of giving rise to an action for damages; (f) the steps, if any, taken by the plaintiff to obtain medical, legal or other expert advice and the nature of any such advice he may have received.” I shall refer to the factors set out in section 33 (3) as “criterion (a)”, “criterion (b)” and so forth. 9. After these introductory remarks, I must now turn to the facts. Double-click to enter the short title Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Part 2. The facts 10. The claimant was born on 8th October 1924 and is now aged 89. He has led an active and varied life. During the Second World War he served as a driver in the army. This included service in France and Germany immediately after the D-Day landings. 11. Between 1947 and 1967 the claimant worked as a dockworker at London Docks. He was based at Tilbury Dock, but sometimes went to other London Docks. Throughout this period the claimant was registered with NDLB and he worked for a number of different stevedoring companies. He recalls that one of those companies was Scruttons. 12. On occasions the claimant assisted in unloading cargos of asbestos. He recalls that the asbestos was usually grey/white, but occasionally it was blue. The asbestos was held in hessian sacks. 13. In about 1967 the claimant became a full-time crane driver. He continued working at London Docks, but his exposure to asbestos came to an end. The claimant remained working as a crane driver until he reached the age of 60 in 1984. He then retired. 14. In early 2002 the claimant became unwell. He suffered weight loss, shortness of breath and other symptoms. He attended the Respiratory Medicine Clinic at Basildon Hospital. In May 2002 Dr Mukherjee, the consultant respiratory physician, diagnosed the claimant as suffering from inoperable lung cancer. He referred the claimant to the Oncology Clinic for palliative radiotherapy. 15. The claimant duly underwent palliative radiotherapy. Happily he proved to be much more resilient than the medical profession expected. The lung cancer abated and the claimant made a good recovery. 16. The doctor who treated the claimant in the Oncology Clinic was Dr Prejbisz. Dr Prejbisz examined the claimant on numerous occasions between 2002 and 2008. He noted a rapid improvement in the claimant’s condition. In 2008 Dr Prejbisz discharged the claimant from further follow-up. 17. In 2008 the claimant developed a bowel problem. This was unrelated to the earlier lung cancer. He saw Dr Lovett in connection with the bowel problem. Dr Lovett successfully treated the claimant for this condition between 2008 and 2010. 18. In July 2009 Corries sought to generate new claims by placing the following advertisement in the Daily Mail: “ASBESTOS COMPENSATION Did you work at any of these between 1940 and 1980? …. Tilbury Docks Double-click to enter the short title Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. …. Are you suffering from any of these? • Lung cancer • Mesothelioma • Asbestosis • Pleural Plaques • Pleural Thickening …. CALL FOR FREE ADVICE 0800 655 6069” The claimant’s wife saw this advertisement. She encouraged her husband to respond. The claimant duly telephoned the number given in the advertisement and spoke to Corries. 19. Corries investigated the claimant’s claim in a somewhat leisurely manner. They sent a letter of claim to the first defendant on 16th November 2009 and a letter of claim to the second defendant on 10th November 2010. In May 2012, almost three years after they had been instructed, Corries commenced the present proceedings. Part 3. The present proceedings 20. By a claim form issued in the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court on 22 nd May 2012 the claimant claimed damages for personal injuries against both defendants. He asserted that both NDLB and Scruttons had acted negligently and in breach of statutory duty by exposing him to contact with asbestos. This caused him to develop the lung cancer which was diagnosed in 2002. Both defendants served defences, denying the alleged breaches of duty and causation. The defendants also asserted that the claimant’s claims were barred under the Limitation Act. 21. Master McCloud ordered the trial of a preliminary issue, to determine whether the claimant’s claims were barred by limitation. 22. The trial of the preliminary issue took place before Mr Justice Nicol on 24th and 25th April 2013. The claimant and his wife gave oral evidence. The claimant put his expert reports before the court as written evidence. The defendants relied upon witness statements made by their respective solicitors. I shall return, in so far as necessary, to the details of the evidence in Parts 5 and 6 below. 23. The judge handed down his reserved judgment on 2nd May 2013: see Collins v Secretary of State for Business Innovation and Skills [2013] EWHC 1117 (QB). He upheld the limitation defences of both defendants and dismissed the action. I would summarise the judge’s findings and reasoning as follows: i) The claimant did not have actual knowledge of the possible link between his lung cancer and his previous exposure to asbestos until July 2009 when he saw the advertisement. Therefore he commenced proceedings within the requisite three year period after the date of actual knowledge. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. 24. Double-click to enter the short title ii) The claimant had constructive knowledge under LA section 14 (3) of the possible link in mid-2003. This is because, as a reasonable man, he should by then have asked Dr Prejbisz about the possible causes of his cancer. If the claimant had done so, Dr Prejbisz would have mentioned asbestos exposure as a possible cause. iii) Therefore under LA section 11 the limitation period expired in mid-2006. The claimant commenced his actions six years after expiry of the limitation period. iv) Upon application of the criteria set out in LA section 33, it did not appear equitable to disapply the provisions of section 11. Therefore the defendants’ limitation defences succeeded. The claimant was aggrieved by the judge’s decision on limitation. Accordingly he appealed to the Court of Appeal. Part 4. The appeal to the Court of Appeal 25. By an appellant’s notice filed on 24th May 2013 the claimant appealed to the Court of Appeal, essentially on two grounds, namely: i) The judge erred in finding that the claimant had constructive knowledge in mid-2003. The claimant did not acquire constructive knowledge at any time before July 2009. ii) The judge erred in the exercise of his powers under LA section 33. He ought to have disapplied the provisions of LA section 11. 26. There is no respondent’s notice. No party disputes the date of actual knowledge found by the judge. 27. One other matter is common ground between the parties. This is that the word “attributable” in section 14 (1) (b) of the Limitation Act means “capable of being attributed to” in the sense of being a real possibility. The attribution does not need to be a matter of certainty. See Spargo v North Essex District Health Authority [1997] EWCA Civ 1232; [1997] PIQR P235. 28. Having set the scene, I must now address the first ground of appeal, concerning the date of constructive knowledge. Part 5. The date of constructive knowledge 29. The claimant made three witness statements for the purpose of the preliminary issue trial. At paragraph 10 of his third witness statement he said: “I do not recall having asked the doctors what caused the lung cancer at the time. At the time I was more concerned about how long I would have left. At the time I was only given a couple of months to live. However, in later years I did ask one of the doctors, Dr Lovett, who was treating me for a bowel problem, what might have caused the lung cancer but she could not tell me. I also recall asking Dr Prejbisz, my oncologist, but he said Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title that he could not say as he simply did not know what had caused it. He just told me that I had it, it was cured and that I have now got over it.” The judge accepted this evidence. 30. In cross-examination the claimant said that his conversation with Dr Prejbisz came after his conversation with Dr Lovett. This implies that the claimant had both those conversations in 2008. The claimant started consulting Dr Lovett in 2008 and his follow-up sessions with Dr Prejbisz ended later that year. 31. Having accepted the claimant’s factual evidence as to what actually happened, the judge went on to make two crucial findings about what should and would have happened. These were: 32. i) It was reasonable for the claimant not to make inquiries about the cause of his cancer in the period immediately after he had received such a devastating diagnosis. Nevertheless by mid-2003 it would have been reasonable to expect the claimant to ask Dr Prejbisz about the possible causes of his lung cancer: judgment paragraph 28. ii) If asked, it was “inconceivable” that Dr Prejbisz would not have mentioned asbestos exposure as a possible cause: judgment paragraph 27. Mr Simon Kilvington, on behalf of the claimant, attacks both of those findings. I shall deal with them in turn. (i) As a reasonable man, should the claimant have inquired about the possible causes of his lung cancer by mid-2003? 33. The courts have considered the operation of LA section 14 (3) on a number of occasions. The two most important decisions for present purposes are Adams v Bracknell Forest Borough Council [2004] UKHL 29; [2005] 1 AC 76 and Johnson v Ministry of Defence [2012] EWCA Civ 1505; [2013] PIQR P7. 34. In Adams A attended the defendant’s schools between 1977 and 1988. He had always experienced difficulties with reading and writing and as an adult found those difficulties to be an impediment in his employment. He believed them to be the cause of the depression, panic and lack of self-esteem which he suffered. He consulted his doctor about those conditions, but was too embarrassed to disclose his literacy difficulties during the consultations. In 1999, when aged 27, he met by chance an educational psychologist, who suggested that he might be dyslexic. Upon a doctor confirming that diagnosis the appellant, in 2002, issued proceedings against the defendant. He claimed damages for negligence on the grounds of the defendant’s failure properly to assess the educational difficulties he had experienced at school. He said that such an assessment would have revealed that he suffered from dyslexia and led to treatment to ameliorate the consequences of that condition. 35. A’s claim failed on the issue of limitation. The House of Lords held that A could reasonably have been expected to seek professional advice before 1999. Therefore A had commenced proceedings more than three years after the date of constructive Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title knowledge. In arriving at this conclusion the House of Lords held that the test to be applied under section 14 (3) was an objective one. The court must disregard the particular characteristics of A and decide what inquiries a reasonable person, who had suffered A’s injury, would make. The normal expectation was that someone who had suffered a serious injury would seek professional advice as to the cause. 36. In Johnson J claimed that his former employers had exposed him to excessive noise during the course of his employment and that this had caused deafness. J became aware of his hearing problems in 2001. He was also aware that exposure to noise could cause hearing loss. However, he did not associate his own hearing problems with exposure to noise in earlier years. In 2006 he consulted a doctor, asking if he had wax in his ears. The doctor attributed J’s hearing difficulties to ageing. In 2009 J saw a consultant who advised that he had noise induced hearing loss. He then issued proceedings. The trial judge dismissed J’s claim on limitation grounds and the Court of Appeal upheld that decision. 37. The Court of Appeal held that a reasonable person in J’s position would have been curious about the cause of his deafness. He would have consulted his general practitioner. The doctor would probably have asked him about his employment history. This would have led to possible attribution of the claimant’s deafness to exposure to excessive noise at work. Allowing a year or so for consideration, J was fixed with constructive knowledge about the possible cause of his deafness by the end of 2002: see the judgment of Dame Janet Smith (with whom Etherton and Hallett LJJ agreed) at [21] to [31]. 38. Because the test in section 14 (3) is an objective one, the practical consequence is that some injured persons fail to make reasonable and timeous inquiries, with the result that they are time-barred. This is unsurprising. Sections 11 to 14 of the Limitation Act strike a balance between the interests of (a) persons who, having suffered latent injuries, seek compensation late in the day and (b) tortfeasors who, despite their wrongdoings, ultimately need closure. Parliament has struck that balance by means of an objective test. Parliament has also provided a safety net in the form of section 33 so as to prevent injustice arising. 39. Let me now revert to the present case. In my view, applying the objective test, that judge was entirely right to say that a reasonable person in the claimant’s position would have asked about the possible causes of his lung cancer by mid-2003. This inference is entirely consistent with the approach of the House of Lords in Adams and the approach of the Court of Appeal in Johnson. 40. The medical records reveal that during 2002 at least one doctor questioned the claimant about his lifestyle and former employment. Obviously the doctor was asking these questions for a purpose. Any reasonable person in the claimant’s position would have been prompted to inquire what light this shed upon the possible causes of his cancer. 41. Mr Kilvington points out that on the judge’s findings the claimant did not in fact ask the doctors about these matters until 2008. Furthermore, when he did so, he asked what was the cause, not the possible cause, of his lung cancer: see paragraphs 13 and 26-28 of the judgment. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title 42. In my view the fact that the claimant delayed for six years before asking the obvious question does not assist his case. A reasonable person would have been prompted to inquire sooner. The way in which the claimant chose to formulate his question in 2008 does not assist in determining how the claimant would or should have formulated any similar question in 2002/3. 43. Finally on this issue, for reasons to be set out in the next section, the precise formulation of the claimant’s question in 2002/3 is irrelevant. Whether he had asked about “causes” or “possible causes”, he would probably have received the same answer. (ii) What would Dr Prejbisz have said, if asked about the possible causes of the claimant’s lung cancer in 2003? 44. Mr Kilvington relies heavily upon the judge’s finding that in 2008 the claimant asked Dr Lovett and Dr Prejbisz about the cause of his lung cancer and their answer was that they did not know. 45. For present purposes the answer given by Dr Lovett is irrelevant. She did not come on the scene until 2008. She was dealing with the claimant’s current bowel problem, not his earlier episode of lung cancer. 46. The answer given by Dr Prejbisz is more important. He worked in the Oncology Clinic and is the doctor whom the claimant should have questioned in 2002/3. It is therefore necessary to look more closely at what he said in 2008. According to the claimant’s evidence (which the judge accepted) Dr Prejbisz “could not say as he simply did not know, what had caused it. He just told me that I had it, it was cured and that I have now got over it”. 47. 2008 was the year in which Dr Presbisz discharged the claimant from follow-up. He was dealing with an 84 year old man who had suffered lung cancer six years earlier and who had been completely cured. Dr Prejbisz’s somewhat brusque response in 2008 does not assist in determining what he would have said, if asked about the matter in 2002/3. 48. The judge has held that, if asked about possible causes in 2002/3, “it is inconceivable that Dr Prejbisz would not have mentioned asbestos exposure”: see paragraph 27 of the judgment. That conclusion must be correct. The medical records of 2002 contain several references to the claimant’s employment history and his exposure to asbestos. For example, Dr Prejbisz wrote a fairly full note about the claimant’s diagnosis and history after examining him on 30th May 2002. This included the entry: “previously worked with asbestos at Tilbury Docks”. 49. Dr Prejbisz would have known that exposure to asbestos was one of the possible causes of lung cancer. If asked about the matter in 2002/3, when the question was relevant, I agree with the judge it is inevitable that Dr Prejbisz would have mentioned exposure to asbestos as a possible cause of the claimant’s lung cancer. In my view, this is the case however the claimant had formulated his question. If the claimant had simply asked “what is the cause?”, Dr Prejbisz while saying that he did not know for certain would have mentioned exposure to asbestos as a possible cause. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title 50. Let me now draw the threads together. For the reasons set out above, I agree with the judge’s decision that the claimant had constructive knowledge by the middle of 2003. I therefore reject the claimant’s first ground of appeal. 51. I must now move on to the second ground of appeal, concerning the application of section 33 of the Limitation Act. Part 6. The application of section 33 of the Limitation Act 1980 52. The claimant contends that the judge erred in failing to disapply the limitation provisions in the exercise of his power under LA section 33. 53. The claimant’s main attack is directed to paragraphs 9 to 12 of the judgment. In that section the judge held that he could take into account prejudice which the passage of time between 1947 and 2003 had caused to the defendants. Counsel on both sides identified this matter as the main issue of principle in the appeal. I must therefore review the authorities which counsel have cited in support of their respective positions. 54. In Donovan v Gwentoys Ltd [1990] 1 WLR 472 a 16 year old girl slipped and fell whilst employed at the defendant’s factory. The limitation period expired on her 21 st birthday. She commenced proceedings five and a half months after that date. The judge extended time under LA section 33, holding that he could only consider prejudice suffered by the defendant in the last five and a half month period. The Court of Appeal upheld that decision, but the House of Lords reversed it. The House of Lords noted that the opening words of section 33 (3) required the court to “have regard to all the circumstances of the case.” That provision enabled the court to take into account prejudice caused to the defendant by the plaintiff’s delay over the entire period since her accident. 55. At pages 479 to 480 Lord Oliver (with whom Lord Bridge, Lord Templeman and Lord Lowry agreed) said this: “The argument in favour of the proposition that dilatoriness on the part of the plaintiff in issuing his writ is irrelevant until the period of limitation has expired rests upon the proposition that, since a defendant has no legal ground for complaint if the plaintiff issues his writ one day before the expiry of the period, it follows that he suffers no prejudice if the writ is not issued until two days later, save to the extent that, if the section is disapplied, he is deprived of his vested right to defeat the plaintiff's claim on that ground alone. In my opinion, this is a false point. A defendant is always likely to be prejudiced by the dilatoriness of a plaintiff in pursuing his claim. Witnesses' memories may fade, records may be lost or destroyed, opportunities for inspection and report may be lost. The fact that the law permits a plaintiff within prescribed limits to disadvantage a defendant in this way does not mean that the defendant is not prejudiced. It merely means that he is not in a position to complain of whatever prejudice he suffers. Once a plaintiff allows the permitted time to elapse, the defendant is no Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title longer subject to that disability, and in a situation in which the court is directed to consider all the circumstances of the case and to balance the prejudice to the parties, the fact that the claim has, as a result of the plaintiff's failure to use the time allowed to him, become a thoroughly stale claim, cannot, in my judgment, be irrelevant.” 56. In Donovan the plaintiff was aware of all relevant facts on the date of the accident. It was therefore possible for Lord Oliver to characterise her inaction over the entire five year period between the date of the accident and the date of issuing the writ as “dilatoriness”. In a case such as the present, where there is a time lag between breach and causation of injury, then a further time lag before the date of constructive knowledge, it is not possible to characterise the claimant’s inactivity over the entire period since 1947 as “dilatoriness”. 57. In Price v United Engineering Steels Ltd [1998] PIQR P407 the plaintiff claimed damages for deafness induced by exposure to excessive noise during his employment with the first and second defendants some 20 to 35 years previously. He issued his writ six years after the date of knowledge under LA section 14 and therefore three years after expiry of the limitation period. The judge declined to extend time under section 33. In reaching this decision he had regard to prejudice caused by the loss of evidence and records in the period before the plaintiff’s date of knowledge. The Court of Appeal upheld that decision, relying upon the speech of Lord Oliver in Donovan. 58. The significance of Price is this. The Court of Appeal extended the principle stated by Lord Oliver in Donovan so as to cover a period of time before the plaintiff knew, or could have known, that he had a claim. It would not be right to characterise this as “dilatoriness”. “Passage of time” would be a fairer description. 59. In AB v Ministry of Defence [2010] EWCA Civ 1317 a large group of servicemen or their dependants and personal representatives claimed damages for personal injuries suffered as a result of experimental nuclear explosions in the 1950s. On the trial of preliminary issues in ten lead cases Foskett J held that five of the claims had been issued in time and that the other five claims should be permitted to proceed in the exercise of the court’s discretion under section 33 of the Limitation Act. 60. On appeal the Court of Appeal held that only one of the ten claims had been issued in time. Furthermore the judge had erred in the exercise of his discretion under section 33. The nine claims which had been issued out of time should not be allowed to proceed because they had no realistic prospect of success. Smith LJ, delivering the judgment of the court, dealt with generic issues concerning section 33 of the Limitation Act at paragraphs 84 to 111. 61. At paragraph 98 Smith LJ stated that delay going back to the 1950s could be relevant as part of “all the circumstances of the case” under section 33 (3). It was an important issue whether a fair trial of the primary factual issues could now take place. In relation to one of the ten cases (John Allen Brothers) Smith LJ specifically took that Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title historic delay into account, although it is not entirely clear on which side of the scales she placed it: see paragraphs 202-203. 62. AB v Ministry of Defence subsequently went to the Supreme Court ([2012] UKSC 9; [2013] 1 AC 78), but only on issues concerning section 14 of the Limitation Act. The Supreme Court did not consider the operation of section 33 and therefore I need not review the judgments of the Supreme Court. 63. In Davies v Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change [2012] EWCA Civ 1380 a group of miners claimed damages for personal injuries caused by the conditions in which they had worked between 1954 and 1993. Eight representative actions were dealt with first. In each of those eight cases the claim was issued after expiry of the limitation period. On the trial of preliminary issues Judge Grenfell, in the exercise of his discretion under section 33 of the Limitation Act, declined to allow those actions to proceed. At paragraphs 46 to 47 of his judgment Judge Grenfell said that he must take into account the defendant’s difficulties which pre-existed the claimant’s date of knowledge as part of his overall assessment under section 33. 64. The Court of Appeal upheld Judge Grenfell’s decision. Tomlinson LJ gave the lead judgment, with which Mummery and Hallett LJJ agreed. At paragraph 18 of his judgment Tomlinson LJ quoted with approval the passage in Judge Grenfell’s judgment to which I have referred. 65. None of those authorities discussed the issue of pre-limitation period effluxion of time at any length. In a long tail case the problem seems to me to be this. Criterion (b) requires the court to focus specifically upon the extent to which the evidence has become less cogent during the claimant’s delay. If the claimant is out of time, the House of Lords’ decision in Donovan allows the court to take account of prejudice accruing since the date when the claimant knew he/she had a claim. The decisions in Price, AB and Davies establish that the court can also take account of delay before the date of actual or constructive knowledge. On the other hand, it would be absurd if the defendant could rely upon all the prejudice accruing from the date when the breaches of duty occurred, alternatively from the date when (unknowingly) the claimant suffered injury. If all that prejudice could be fully taken into account, section 33 (3) (b) would serve no useful purpose. Loss of cogency of evidence during the limitation period must be a factor which carries more weight than (a) the disappearance of evidence before the limitation clock starts to tick or (b) the loss of cogency of evidence before the limitation clock starts to tick. Furthermore both the claimant and the defendant may rely upon the effects of delay before the limitation clock starts to tick for different purposes. 66. Construing section 33 (3) as best I can in the light of the authorities, my conclusions are: i) The period of time which elapses between a tortfeasor’s breach of duty and the commencement of the limitation period must be part of “the circumstances of the case” within the meaning of section 33 (3). ii) The primary factors to which the court must have regard are those set out in section 33 (3) (a) to (f). Parliament has singled those factors out for special mention. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title iii) Therefore, although the court will have regard to time elapsed before the claimant’s date of knowledge, the court will accord less weight to this factor. It will treat pre-limitation period effluxion of time as merely one of the relevant factors to take into account. iv) Both parties may rely upon that factor for different purposes. The claimant may rely upon the earlier passage of time in order to buttress his case under section 33 (3) (b). The claimant may argue that recent delay has had little or no impact on the cogency of the evidence. The damage was done before the claimant started being dilatory. The defendant may rely upon the earlier passage of time, in order to show that it already faced massive difficulties in defending the action; therefore any additional problems caused by the claimant’s recent delay are a serious matter. It is for the court to assess these and similar considerations, then decide on which side of the scales to place this particular factor. 67. Let me now return to the present case. The judge carried out his evaluation exercise at paragraphs 30 to 48 of the judgment. He treated the criteria set out in section 33 (3) (a) to (f) as the factors of primary importance. He also had regard to the passage of time (some 50 years) between the defendant’s alleged breaches and the claimant’s date of constructive knowledge. He took into account the extent to which this assisted the claimant in relation to criterion (b). More generally he treated the lengthy period of historic delay as a factor making it less equitable to extend time under section 33 (1). The judge did not attach undue weight to this consideration. 68. In my view the judge was entitled to take the period of historic delay into account in the manner that he did. I therefore reject the claimant’s main line of attack on the judge’s decision under section 33. 69. I can deal with the claimant’s other arguments more shortly. In relation to criterion (b), the judge noted numerous inconsistencies between the claimant’s three witness statements, as well as between his written and oral evidence. He attributed these inconsistencies to the claimant’s advancing age. The judge concluded that the evidence had become “less cogent” as a result of the claimant’s six year delay between expiry of the limitation period and issue of proceedings. 70. That is an eminently reasonable conclusion, which is not susceptible to attack on appeal. Mr. Kilvington argues that the claimant’s fading recollection can only harm the claimant’s case, not the defendant’s case. I do not agree. The inconsistencies in the claimant’s factual evidence make it difficult for defendants to instruct their experts and to deal with issues such as apportionment. The judge concluded, and was entitled to conclude, for the purposes of LA section 33 (1) (b) that the claimant’s delay since expiry of the limitation period had caused prejudice to the defendants. 71. Under the heading “other matters” the judge characterised the claimant’s case as weak, in that it would be difficult for him to establish the requisite degree of exposure to asbestos. I am inclined to think that assessment was somewhat harsh. The claimant had the support of two independent experts, as well as one other dock worker from the same period. The defendants have not yet provided any expert evidence to rebut the claimant’s contentions. I would characterise the claimant’s case as “difficult”, rather than weak. Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Double-click to enter the short title 72. The judge also characterised the claimant’s claim as being of relatively low value. I certainly agree with that comment. The claimant suffered from an episode of lung cancer, which happily was cured by radiotherapy. Dr Rudd, the claimant’s medical expert, assesses the risk of recurrence as 2%. The claimant is a man of fortitude, who has led a full life and is now approaching his 90th birthday. Realistically this personal injury claim, which he was induced to bring as a result of advertising by his solicitors, is one of low value. I agree with the judge that there is a disproportion between the litigation costs and the sum in issue. 73. The judge discussed the application of all the section 33 criteria to the facts of this case. Much of that discussion is not seriously criticised. 74. In determining whether to extend time under LA section 33 the judge must consider the matters specifically identified in section 33 (3), as well as all the circumstances of the case. He then carries out an evaluation under section 33 (1) in order to determine whether it would be equitable to allow the action to proceed, having regard to the degree to which (a) the claimant is prejudiced by the time bar and (b) the defendant would be prejudiced if the time bar were lifted. 75. In the present case the judge carefully evaluated all the relevant factors and came to a conclusion under section 33 which is plainly correct. 76. The Court of Appeal is always slow to interfere with an evaluation made by a trial judge who was required to weigh up conflicting considerations. In this case I would go one stage further and say that the judge was obviously correct. I would therefore reject the second ground of appeal. Part 7. Executive summary and conclusion 77. The claimant was diagnosed with lung cancer in May 2002, from which he made a good recovery. He attributes that illness to exposure to asbestos between 1947 and 1967 as a result of the defendants’ negligence and breaches of statutory duty. He issued proceedings in May 2012. The judge held that the claimant’s date of constructive knowledge was mid-2003, with the result that the limitation period expired in mid-2006; accordingly the claimant started his action six years after expiry of the limitation period. The judge declined to extend time under section 33 and dismissed the action. 78. In my view the judge was correct on both issues. As a reasonable person the claimant ought to have asked about the possible causes of his lung cancer by mid-2003. The treating oncologist, who had recorded the claimant’s work with asbestos in his notes, would probably have identified exposure to asbestos as a possible cause. The judge properly weighed up the relevant factors and conflicting considerations under section 33. He was entitled to, and did, take into account the lengthy passage of time between the period 1947 to 1967 (when the defendants allegedly committed breaches of duty) and mid-2003, when the claimant was fixed with constructive knowledge. 79. If my Lord and my Lady agree, this appeal will be dismissed. Lord Justice Lewison: Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. 80. I agree. Lady Justice Macur: 81. I also agree. Double-click to enter the short title