The ADA Amendments Act of 2008

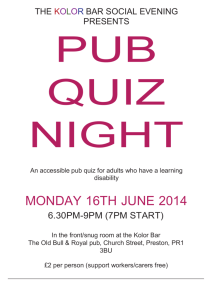

advertisement

The ADA Amendments Act of 2008: Analysis and Commentary By John W. Parry* & Amy L. Allbright** Congress enacted, and President Bush signed into law, the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, in an effort to reinstate “a broad scope of protection to be available under the ADA” for persons with disabilities.1 In the “Findings and Purposes” section, Congress opines that “the question of whether an individual’s impairment is a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) should not demand extensive analysis.”2 Rather, “the primary object of attention . . . should be whether entities covered under the ADA have complied with their obligations.”3 Congress maintains that both the U.S. Supreme Court and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) have misinterpreted the original Act’s language, “thus eliminating protection for many individuals whom Congress intended to protect.”4 At the same time, however, the amended Act contains a number of ambiguities, which Congress does not resolve, but rather directs certain federal agencies and the courts to resolve through rules of construction that favor persons with disabilities. Moreover, the amendments do not necessarily significantly change the most problematic aspect of the previous law, which restricted coverage of actual disabilities to impairments that substantially limit a major life activity. Disability Defined 1 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 2(b)(1), 122 Stat. 3553, 3554. Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 2(b)(5), 122 Stat. 3553, 3554. 3 Id. 4 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 2(a)(4), 122 Stat. 3553. 2 The most significant changes made by the amendments involve the definition of the term “disability.” Congress states that the “definition . . . shall be construed in favor of broad coverage of individuals under this Act, to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of the Act.”5 The amendments also change the definition of “disability” in the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. §705—“a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities”—to conform to that of the amended ADA.6 Major Life Activities Unlike the original 1990 ADA, the amended Act defines the term “major life activities.” Rejecting the Supreme Court’s definition in Toyota Motor Mfg., Ky., Inc. v. Williams,7—“activities that are of central importance to most people’s daily lives”— the amendments list major life activities that are covered. These “include, but are not limited to, caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, lifting, bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating, and working,” as well as “the operation of a major bodily function, including . . . functions of the immune system, normal cell growth, digestive, bowel, bladder, neurological, brain, respiratory, circulatory, endocrine, and reproductive functions.”8 Substantially Limits 5 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. (4)(a)(4)(C), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 7(1) & (2), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. 7 534 U.S. 184 (2002), 26 MPDLR 73. 8 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 4(a)(2)(A) & (B), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. 6 In addition, under the amendments, “the term ‘substantially limits’ shall be interpreted consistently with the findings and purposes” of this Act.9 Congress rejects the Court’s interpretation of the term “substantially limits” in Toyota—“an individual must have an impairment that prevents or severely restricts the individual from doing activities that are of central importance to most people’s daily lives”10—as requiring “a greater degree of limitation than was intended by Congress.”11 Moreover, under the amendments, “[a]n impairment that substantially limits one major life activity need not limit other major life activities in order to be considered a disability.”12 Regarded As Disabled The most significant change Congress makes is to the “regarded as” prong of the disability definition. Congress expressly rejects13 the Court’s ruling in Sutton v. United Air Lines, Inc.,14 that, to be regarded as disabled, the covered entity must mistakenly believe that (1) the individual has a physical impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, or (2) an actual, non-limiting impairment substantially limits one or more major life activities.15 Under the amendments, an individual meets this prong by “establish[ing] that he or she has been subjected to an action prohibited under this Act because of an actual or perceived physical or mental impairment whether or not the impairment limits or is perceived to limit a major life activity.”16 Accordingly, individuals will be covered based on actual or perceived impairments, whether or not these impairments limit or are perceived to limit a major life activity. However, under the 9 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 4(a)(4)(B), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 4(b)(4), 122 Stat. 3553, 3554. 11 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 2(a)(7), 122 Stat. 3553. 12 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(C), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 13 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 2(b)(3), 122 Stat. 3553, 3554. 14 527 U.S. 471 (1999), 23 MPDLR 510. 15 School Board of Nassau County v. Arline, 480 U.S. 273 (1987), 10 MPDLR 150. 16 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(3)(A), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. 10 amendments, employers under Title I, public entities under Title II, and individuals who own, lease (or lease to), or operate a place of public accommodation under Title III do not have to provide individuals regarded as disabled with reasonable accommodations or modifications to policies, practices, or procedures.17 Although an employee no longer has to show that the employer regarded the employee’s impairment as substantially limiting a major life activity, individuals with “transitory and minor” impairments are excluded from coverage, with “transitory” meaning “an impairment with an actual or expected duration of 6 months or less.”18 In rules of construction, the amendments also indicate that “[a]n impairment that is episodic or in remission is a disability if it would substantially limit a major life activity when active.”19 This means that, if the rules of construction are followed as Congress intends, episodic conditions such as diabetes and many severe mental disorders should be assessed in their active states, rather than when the symptoms are less severe or controlled by treatment. The distinction between episodic and transitory appears to be that with an episodic impairment the active and less active or inactive states will recur, while with a transitory impairment the active state ceases within a certain time period— set by the amendments at “6 months or less.” If the transitory impairment lasts more than six months, it should be considered a covered condition. Mitigating Measures While the amended Act retains the “actual” prong of the disability definition—“a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities 17 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 6(a)(1)(h), 122 Stat. 3553, 3558. Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(3)(B), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. 19 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(D), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 18 of such individual”20—Congress specifies that “a determination of whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity shall be made without regard to the ameliorative effects of mitigating measures,”21 thereby rejecting the Court’s ruling in Sutton. Such measures include (I) medication, medical supplies, equipment, or appliances, low-vision devices (which do not include ordinary eyeglasses or contact lenses), prosthetics including limbs and devices, hearing aids and cochlear implants or other implantable hearing devices, mobility devices, or oxygen therapy equipment and supplies; — and lists; (II) use of assistive technology; (III) reasonable accommodations or auxiliary aids or services; or (IV) learned behavioral or adaptive neurological modifications.22 “Ordinary eyeglasses or contact lenses,” defined as “lenses that are intended to fully correct visual acuity or eliminate refractive error,”23 are not mitigating measures,24 while “low-vision devices,” namely those “that magnify, enhance, or otherwise augment a visual image,”25 are.26 The amended Act leaves unchanged the original Act’s definition of the term “auxiliary aids and services.”27 Regulatory Authority 20 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(1)(A), 122 Stat. 3553, 3555. Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(i), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 22 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(i)(I)–(IV), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 23 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(iii)(I), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 24 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(ii), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 25 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(iii)(II), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 26 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(a)(4)(E)(i)(I), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 27 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 4(b)(1)(A)–(D), 122 Stat. 3553, 3556. 21 With respect to the definitions of “disability,” including the rules of construction, and “auxiliary aids and services,” the amended Act authorizes the EEOC, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of Transportation “to issue regulations . . . consistent with” this Act.28 This language would seem to create an opportunity for ambiguity and confusion with regard to new regulations promulgated under the amendments. While all of these agencies are directed to broadly interpret the law to cover persons with disabilities, they may do so with different results unless they all agree to abide by the same set of regulations. Other Changes In addition to the definition of disability, the amended Act makes a number of other changes to the ADA, most of which are relatively minor in terms of their impact. Employment discrimination is now prohibited against a “qualified individual on the basis of disability,”29 rather than the more confusing language in the original Act— “a qualified individual with a disability because of the disability.”30 Also prohibited is the use of “qualification standards, employment tests, or other selection criteria based on an individual’s uncorrected vision” unless “shown to be job-related for the position in question and consistent with business necessity.”31 Moreover, the amendments clarify that nothing in the ADA alters (1) “the standards for determining eligibility for benefits under state worker’s compensation laws or under state and federal disability programs,”32 even if they should discriminate against certain categories of persons with disabilities, or (2) the requirement to make “reasonable modifications in policies, practices, or 28 Pub. L No. 110-325, Sec. 6 (a)(2), 122 Stat. 3553, 3558. Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 5(a)(1), 122 Stat. 3553, 3557. 30 42 U.S.C. §12112. 31 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 5(a)(2)(b), 122 Stat. 3553, 3557. 32 Pub. L. No. 110-325, Sec. 6(a)(1)(e), 122, Stat. 3553, 3557. 29 procedures, . . . unless such modifications would fundamentally alter the nature of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations involved.”33 Conclusion The amendments change the disability definition in a number of significant ways that should benefit certain persons with disabilities, particularly those with severe conditions who have learned how to cope with their impairments. In addition, the amendments strongly encourage the regulatory agencies and the courts to interpret the disability definition in a manner that will benefit as many people with disabilities as possible. For these accomplishments, Congress should be applauded. At the same time, however, Congress has left the most significant problem with the original Act’s definition in place by keeping the substantial limitation language in the “actual” prong. Moreover, the amendments have unnecessarily introduced a number of serious interpretive ambiguities into the law. In many instances, rather than clearly changing the language of the statutory provisions so there will be few or no disagreements about their intended meanings, the House and Senate decided instead to change the rules of construction that should guide the designated federal regulatory agencies and the courts. Curiously, Congress spends a great deal of time in the “Findings and Purposes” section of the amended Act blaming the federal courts, and to a lesser extent the EEOC, for the fact that so few people with disabilities are actually covered under the original Act’s disability definition. Yet, instead of correcting all the major problems it identifies with specific language changes, in a number of instances Congress has decided to compel those very federal courts to reinterpret the offending statutory language in new ways, 33 Pub. L. No. 110-325 Sec. 6(a)(1)(f), 122 Stat. 3553, 3557. which supposedly will result in expanded coverage for people with disabilities. In reinterpreting “disability,” these courts will be expected to defer to the regulations issued by the three key federal agencies involved, including the EEOC. Unfortunately, these regulations may or may not be the same or as expansive in covering persons with disabilities as Congress indicates—not mandates—that they should be. To a large extent, what actually happens will depend on which party and which key individuals at the lead agencies control the promulgation of the regulations, and which justices are sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court. Depending on how the regulatory agencies and the federal courts resolve the inherent ambiguities, ultimately these amendments may be viewed by the disability community as being either clever and groundbreaking, convoluted, and/or only somewhat less disappointing than the original ADA. *John W. Parry, J.D., is the Director of the Commission on Mental and Physical Disability Law and the Editor-in-Chief of the Mental & Physical Disability Law Reporter. ** Amy L. Allbright, J.D., is the Managing Editor of the Reporter.