narratives civilization

advertisement

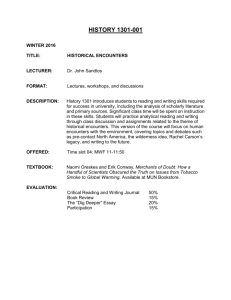

Thesis-Abstract for Professor Bo Stråth’s Seminar Writing History, 29. October 2001 by Hagen Schulz-Forberg ___________________________________________________________________________ 2 ½ Metropolises English, French and German Travel Writing on London, Paris and Berlin, 1851 to 1939 ___________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Chapter I : Conditions a) Nationalism, Tourism, Travel b) Travel Writing - Genre Aspects c) Methodology Chapter II : 2 ½ Metropolises a) London b) Paris c) Berlin Chapter IV : Sound & Vision a) Inter-Sensuality, Inter-Mediality and the Magic of the Moment b) Dissolving Views c) Live Recordings Chapter V : Lasting Ideas a) Locations of Liberty in London b) Civilization, Art and Europe Conclusions Chapter III : Encounters a) National Encounters English French German b) Female/Male Encounters c) Stereotypical Encounters Class Minorities Cast of Characters Biographical Notes on Travel Writers Bibliography The title of my dissertation refers to the metropolises-status of the three cities under study. Since, during my period, Berlin is only on the way of becoming a metropolis, it constitutes the ½ of the title. My sources are published travel writings, that is: books intentionally written to describe and explain the foreign capital. I compare English and German travel writings to Paris, German and French travel writings to London, and French and English travel writing to Berlin. At the beginning I structured my thesis among national divides and chronologically. After reading the travel books intensively I found that they constitute a European genre, indeed, an almost universal genre when reading travel writings from the Arab world to Europe, for example, and finding the same anthropological curiosity; all travel writers have the same set of questions and the same interest. The answers to these questions are different because of the physiognomy of the city and the supposed national characters, which is scrutinized in an anthropological way by the authors. The comparative element of the study is not lost, rather, through describing the foreign nation, travel writers have to state something on their own nation as well, there is thus in every interpretation done by the travel writers an inherent comparison without which there could be no interpretation at all; Michel de Certeau has pointed this out. The time frame is 1851 to 1939 because these two dates mark great divides. In the 1850s, after the bourgeois revolutions, a communicational revolution took place as well: train and steam engine brought people and information closer together. On top of it, as Roland Barthes claimed, all ‘classical’ pieces of literature are disintegrating. Furthermore, the modern urban discourse, the mythology of the metropolis is beginning to root itself firmly at that time with Hugo, Baudelaire and Dickens as some of the representatives. In 1939, travel was hindered through the Second World War and after it the old narratives began to erode. Additionally, my period is the high period of nationalism, official nationalism, that is. It is the period of industrialization, in which all great cities experienced a fungus-like growth, providing a colourful background for the traveller’s investigations. In the big cities everything which characterizes a nation was focused. And travellers could go there and interpret it. Furthermore, all problems of the modern society are found in the cities as well: crime, prostitution, social problems, workers, female rights movements, construction work, monuments representing the nation, the state of art, civilization and culture was under scrutiny, nothing less. The period between 1851 and 1939 is also a period of coherency within the genre of travel writing in Europe. Throughout the first half of the 19th century writers such as Gerard de Nerval, Charles Dickens and Heinrich Heine helped the genre to gain a literary quality and to be able to adapt to modern urban times, actually becoming a great amplifier of the urban mythologies by adapting to them through a newly employed feuilleton-like style of writing. After 1939, the narrative structures changed as well as the whole set-up of Europe. Travel writing was only reborn as a genre in the 1970s, this time in a post-modern form though it ahs always been very self-reflexive. Chapter I : Conditions In the first chapter I elaborate on the points raised above in detail, discussing: • the genre of travel writing • the phenomenon of tourism and nationalism • the urban discourse Furthermore, I show how alike travel writing and historiography are, exploring • historiographical theory • modes of interpretation • formal aspects of both travel writing and historiography • proposing of a methodology which finds itself from within the sources in reference to the interest of the historian, I call ‘dialogical hermeneutics’ Chapter II : 2½ Metropolises This chapter is dedicated to the three cities. I explore the description and interpretation of the metropolises and follow the travellers’ route both through the physical reality of the cities as well as through the interpretative picture they draw. I will show how the points of reference which characterize the cities and their people change through time and present a sometimes different picture on the whole. I conceive of this like of a children’s game in which you have to connect numbers and through the line drawn between the numbers an image becomes visible. Throughout my period the numbers, or the points of reference, the sights, which are connected change and thus create a different final picture, even though sometimes only slightly so. In the case of Berlin and the Germany it represents these changes are most obvious. Yet London and Paris change as well. Chapter III : Encounters This chapter reflects the ‘standard’ approach to travel literature, taking heed of the encounters with the foreign nation. How do German and French travellers perceive the English and vice versa. The chapter is grouped thematically, beginning with the general features associated with the different nations and their changes, and continuing with female/male encounters, with special female and male characters as well as general gender characteristics; finishing with an analysis of stereotypical encounters of class, minorities and individual characters. Chapter IV : Lasting Ideas This chapter deals with two conglomerates of ideas: liberty and Europe. Both play a vital role in the discussion of the other societies. Liberty is followed through the writings on London and Paris, reflecting on the English and French position as well and thus combining all three different versions of liberty in the two capitals of liberty, of individual and of egalitarian liberty, as they were regarded by most writers. Berlin is described implicitly in the German accounts. The factor of Europe unites all travel writers throughout the period since Europe, or European, is a sign of quality. Opera houses, theatres, architecture, science, everything supposedly cultural or ‘civilizational’ or artistic is put into a competitive context of which the arbiter is ‘Europe’. The concepts of Art, Civilization and Europe are thus an entrance for me to the understanding of cultural achievements as well as to social standards since social systems were also put into a comparative and competitive context. Chapter V : Sound & Vision This chapter is about the inter-sensual meaning making process in travel writing, taking into account sounds, smells, and images, and will be applied to all three cities. I will work on the following points. • theory of inter-mediality and inter-sensuality • visual perception and perception theory, based on Merleau-Ponty and Gombrich as well as modern media theories and historical works on the subject. • show how different media interact to create the uniqueness of each city. London smells different from Berlin and this is a vital point in the meaning making process. In travel writing, meaning collapses into an (imagined) immediacy of experience through which the writer is able to disentangle the threads that make up the labyrinth of the foreign nation; it is as well the technique of the genre to achieving credibility. This chapter is thus vital for the understanding of travel writings and the meaning making process in general even though focusing on the three capitals. It is designed on the one hand to present a new theory and on the other hand to bring together all the narrative threads of the first four chapters. Conclusions The results of my work lead to insights on the quality of travel writing within the network of public communication and will also show that existed a network of relation, a discursive as well as a personal one, which changed from within, slowly but continuously, because of, besides other things, the market place, which demanded novelties and new insights on the foreign nation, creating a phenomenon which can be termed ‚forced subjectivity‘. Sometimes old insights were gained through new sings as well. Furthermore, narrative structures of the metropolis become visible, enscribed in its physical reality by each culture, society and nation and the perception of these features. That these phenomena are indeed narratives becomes obvious after the First World War, when almost all pre-war narratives, thought to be and retold as lasting truths, as facts, turned out to be not apt anymore and the stories of the big city had to change slightly, had to find new characters. The Second World War dealt a deadly blow also to most of the surviving narratives and left the metropolises as a sort of tabula rasa. Surely, some tales still haunted the big cities, but to a large degree they had to be re-invented. This shows how important, in the end, is the physical reality of the cities in providing access to the invisible world of cultural or national meaning. In one sign, at a certain point in time and at a certain place, a whole society can be concentrated and thus accessed. And it is exactly these signs that are sought for and necessarily found by travel writers. Details, which either represent a characteristic feature or render the whole foreign nation accessible in a concentrated way. My approach, which is a cultural historical approach of interpretation and does not understand itself in a necessary opposition to social or economic history, but rather as a tool for understanding historical sources and discourses, enables me to gain insights into travel literature, national identities, European self-understanding, political and social conditions as well as projections into the past and future, into phenomena, which are all found in the big cities. These metropolises are thus turned into a sort of time-machine, which can take you into the past, the present and the future alike. In the sign labyrinth of big cities, the diachronic quality of the synchronic experience can be perceived at every corner.