a short paper gathering research, containing links to 6+1 Traits

Roosevelt High School

Writing Curriculum

6+1 Traits

Basic definitions and questions.

(For online scoring practice, see http://www.nwrel.org/assessment/ScoringPractice.asp?odelay=3&d=1 )

The 6+1 Traits system works on a scoring scale of 1 to 5. The 6+1 traits are: Ideas, Organization, Voice, Word

Choice, Sentence Fluency, Conventions and Presentation.

The following is a rough schematic of how the 6+1 Traits match up to the new Minnesota Language Arts standards for grades 9-12.

(See http://education.state.mn.us/content/009200.pdf

for the full standard.)

A. Type of Writing

Standard: The student will write in narrative, expository, descriptive, persuasive and critical modes.

The student will:

1. Plan, organize and compose narrative, expository, descriptive, persuasive, critical and research writing to address a specific audience and purpose.

ORGANIZATION

B. Elements of Composition

Standard: The student will engage in a writing process with attention to audience, organization, focus, quality of ideas, and a purpose.

The student will:

1. Generate, gather, and organize ideas for writing. ORGANIZATION

2. Develop a thesis and clear purpose for writing. ORGANIZATION / IDEAS

3. Make generalizations and use supporting details. ORGANIZATION / IDEAS

4. Arrange paragraphs into a logical progression. ORGANIZATION

5. Revise writing for clarity, coherence, smooth transitions and unity. IDEAS / SENTENCE FLUENCY

6. Apply available technology to develop, revise and edit writing.

7. Generate footnotes, endnotes and bibliographies in a consistent and widely accepted format.

CONVENTIONS / PRESENTATION

8. Revise, edit and prepare final drafts for intended audiences and purposes. CONVENTIONS / PRESENTATION

C. Spelling, Grammar and Usage

Standard: The student will apply standard English conventions when writing.

(Use of standard English conventions is necessary to help a writer convey meaning to the reader. Spelling, grammar, and usage may be taught as a separate unit as well as integrated into teaching writing processes.)

The student will:

1. Understand the differences between formal and informal language styles and use each appropriately. CONVENTIONS / SENTENCE FLUENCY

2. Use an extensive variety of correctly punctuated sentences for meaning and stylistic effect. CONVENTIONS

3. Edit writing for correct grammar, capitalization, punctuation, spelling, verb tense, sentence structure, and paragraphing to enhance clarity and readability: CONVENTIONS a. Correctly use reflexive case pronouns and nominative and objective case pronouns, including who and whom . CONVENTIONS / WORD CHOICE b. Correctly use punctuation such as the comma, semicolon, colon, hyphen, and dash. CONVENTIONS c. Correctly use like/as if, any/any other , this kind/these kinds , who/that , and every/many when they occur in a sentence.

CONVENTIONS / WORD CHOICE d. Correctly use verb forms with attention to subjunctive mood, subject/verb agreement, and active/passive voice. CONVENTIONS / WORD CHOICE e. Correctly use the possessive pronoun before the gerund. CONVENTIONS / WORD CHOICE

As you can see from this rough association of the 6+1 Traits with the MN standards, Organization and

Conventions are the most heavily weighted aspects of writing. When formulating a school-wide policy on writing, it will be necessary to discuss how closely the building standards will mirror the state standards (for example; the MN standards do not address “student voice;” should this trait remain part of the Roosevelt standard?).

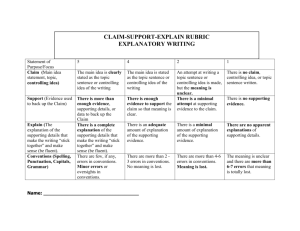

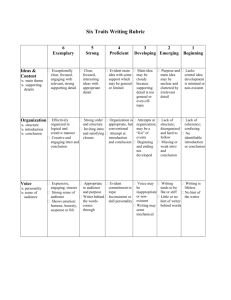

BASIC DEFINITIONS OF THE 6+1 TRAITS:

(expanded definitions available at http://www.nwrel.org/assessment/definitions/asp?d=1 )

Ideas : the Ideas are the heart of the message, the content of the piece, the main theme, together with all the details that enrich and develop that theme.

Organization : Organization is the internal structure of a piece of writing, the threat of central meaning, the pattern, so long as it fits the central idea.

Voic e: The Voice is the writer coming through words, the sense that a real person is speaking to us and cares about the message.

Word Choice : Word Choice is the use of rich, colorful, precise language that communicates not just in a functional way, but in a way that moves and enlightens the reader.

Sentence Fluency : Sentence fluency is the rhythm and flow of language, the sound of word patterns, the way in which the writing plays to the ear.

Conventions : Conventions are the mechanical correctness of the piece – spelling, grammar and usage, paragraphing (indenting at appropriate spots), use of capitals, and punctuation.

Presentatio n: Presentation combines both the visible and verbal elements; it is the way we ‘exhibit’ our message on paper.

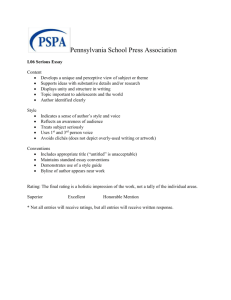

The Scoring System:

(more complete information at http://www.nwrel.org/assessment/pdfRubrics/6plus1traits.PDF

)

1: not yet

2: emerging

3: developing

4: effective

5: strong

Since one possible purpose of moving to a 6+1 Traits model in the building is the ability to combine and present data about the writing of the entire student population (and to disaggregate that data into various subgroups), it is worth considering the following before implementing any changes:

Part I: Preliminary questions

1. What do you want to know? a. About or from students? b. About or from teachers? c. About or from administrators?

2. How will you go about getting this information?

3. Who is this information for?

4. What use will be made of this information?

5. What form will the information take? Will there be a report? Who will write it?

6. What verification or corroboration will ensure the accuracy and consistency of the information?

7. How will the information be collected and how will the way it is collected help to improve the program being assessed?

8. Who will be affected most by the assessment, and what say will they have in the decisions made on behalf of the assessment?

9. What are the major constraints in resources, time, institution, politics, etc.?

Part II: Guiding Principles:

Site-based

Locally controlled

Research-based

Questions developed by whole community

Writing teachers and administrators initiate and lead assessment

Build validation arguments for all assessments

Practice writing assessment

-from Huot, B. (2002). (Re)articulating writing assessment for teaching and learning . Logan, Utah: Utah State UP.

What is important in considering changes to writing curricula and writing assessment practice, especially when the changes involve the collection of data to make judgments about student and teacher performance, is creating a clear idea of what your current (unmet?) needs are and how a change in curriculum can help.

For instance, some (very) general guiding principles of good writing curricula would be:

1.

Prewriting and Revising are essential to good writing.

2.

Writing should happen everyday in class (or as often as possible). Use a range of writing activities (the 5 Types of

Writing are very useful for this —do a Type 1 or Type 2 every day)

3.

An expectation of “Audience” helps writers to situate their texts grammatically, rhetorically and structurally.

4.

Student-Teacher and Peer to Peer conferences should happen on each text (Type 3 and above).

5.

students need training on how to provide specific, descriptive feedback prior to beginning conferences

6.

vary conference styles to provide struggling writers with more direct guidance and modeling of self-assessing, but still allowing students independence to make their own decisions

7.

Have students complete multiple drafts of each piece with feedback along the way. DO NOT view revision is a matter of grammar and spelling only!

8.

Writing assessment should be as holistic as possible, preferably based on portfolios (these would, ideally, collect writing from “across the curriculum” so that it truly represents varying rhetorical modes, purposes and genres).

9.

Writing assessment should be rhetorical and situated toward helping the student become a better writer.

10.

For each individual assignment, assessment (and grading) should focus on a small number of concerns ideally concerns that the class spends time in class studying in brief “mini-lessons” (these can be grammatical, rhetorical, structural, etc.).

11.

Formulate criteria for assignments that specify specific expectations for quality for that assignment (as opposed to more generic criteria). And, teachers and students should discuss those criteria so that there are clear to the students, as well as letting students contribute to defining criteria.

There’s no reason to think that all of these are appropriate or necessary parts of your writing curriculum. For instance, Diana R. Ferris ( Response to student writers: Implications for second language students , 2003) has shown that ESL students do not necessarily benefit from peer to peer conferencing in the same ways as native

English speakers. Further, she notes that ESL students tend to “value and appreciate teacher feedback in almost any form” (103), something which does not hold up in research on native speakers.

Returning to the earlier question of “What are the major constraints in resources, time, institution, politics, etc.?,” it is worth considering, very seriously, restraints on teacher time in formulating new writing assessment practices. In particular, we should consider the following practices for writing assessment which are supported by research on both native and ESL students:

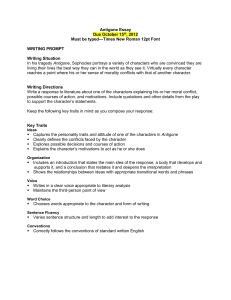

1. Read the paper through once without making any marks or other comments on it.

2. Write an endnote (either at the end of the paper itself or on a separate feedback form if you are using one) that both provides encouragement and summarizes several specific suggestions for improvement.

3. Add marginal comments, if desired, that provide specific examples of general points you have raised in the endnote.

4. Check both your endnotes and your marginal notes for instances of rhetorical or grammatical jargon or formal terminology (thesis, subject-verb agreement) that may be unfamiliar to the student.

5. If you write comments in the form of questions, check them carefully to make sure that the intent of the question is clear, that the answer to the question, if provided, would actually improve the quality of the paper, and that the student will know how to incorporate the ideas suggested by the questions in their existing text.

6. Whenever feasible, pair questions and other comments with explicit suggestions for revision.

7. Use words or phrases whenever possible instead of codes or symbols.

8. Design or adapt a standard feedback form that is appropriate to the goals and grading criteria of your course.

9. Do not overwhelm the student writer with an excessive amount of commentary.

10. Be sure that your feedback is written legibly.

(from Ferris, 2003, p. 125).

How long, realistically, will it take for teachers to respond to student writing? How often should building-wide assessment (for the collection of data) take place? How will the data collected be used to reflect on and drive teaching practice?

Since the construction of a standard feedback form (#8 above) involves an electronic document which enables the summation of data for the whole school, it is important to consider whether students and parents will have access to these forms (or just to the written comments of the teacher as described above). That is, is the collection of data about student writing for the teachers and administrators only or is it also for students, parents, etc.

?

Finally, student writing and teacher assessment do not happen in a vacuum. It might therefore be worthwhile to consider the following:

1.

What does the teaching of writing look like in Roosevelt classrooms?

2.

What does feedback to student writing currently look like?

3.

4.

5.

6.

What do students think about that feedback?

How effective do teachers think their current feedback is? How do they know?

What type of writing assignments are students currently expected to complete?

Is there a consistent building-wide approach to writing and writing assessment?

8.

7.

Should there be?

Is it possible to change how writing is assessed without changing the way writing is taught and practiced in the building?

Because of these, would collecting and analyzing (some of) the following things be worthwhile?

Video or audio recordings of classes

Surveys and/or interviews regarding student views of how writing assessment is handled

Current writing prompts and assignments

Examples of already-existing teacher feedback on student writing

Surveys or interviews regarding teacher views on how writing assessment is handled