Executive Summary - State of Rhode Island General Assembly

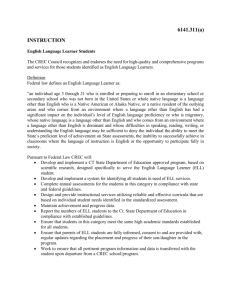

advertisement