Teaching modes of discourse

advertisement

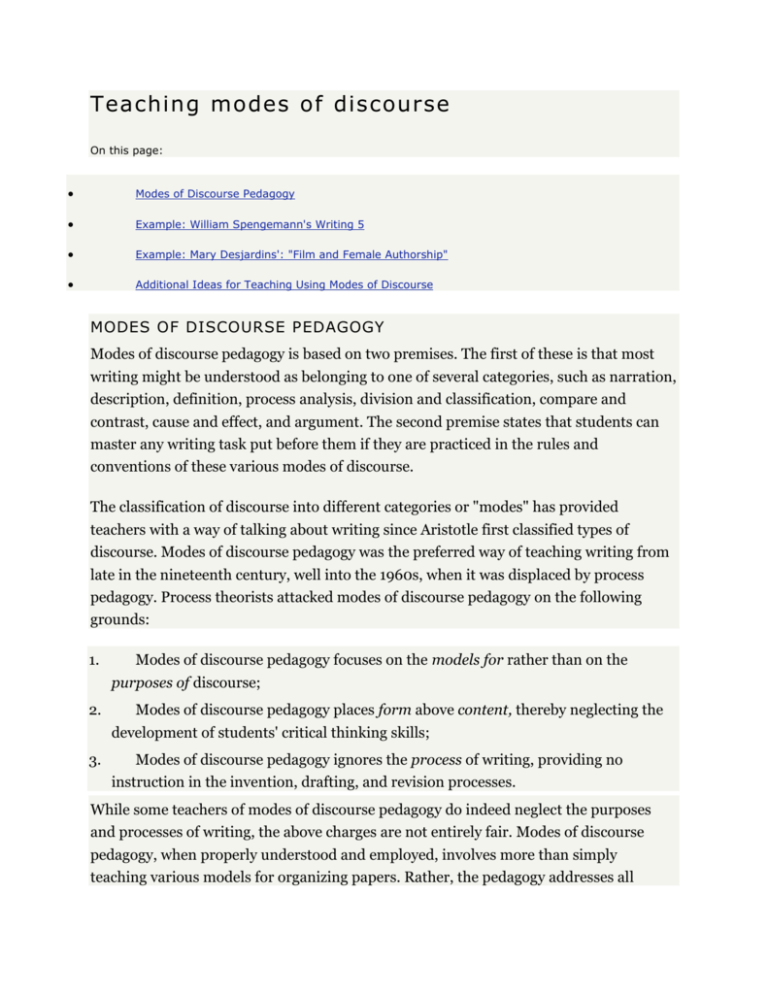

Teaching modes of discourse On this page: Modes of Discourse Pedagogy Example: William Spengemann's Writing 5 Example: Mary Desjardins': "Film and Female Authorship" Additional Ideas for Teaching Using Modes of Discourse MODES OF DISCOURSE PEDAGOGY Modes of discourse pedagogy is based on two premises. The first of these is that most writing might be understood as belonging to one of several categories, such as narration, description, definition, process analysis, division and classification, compare and contrast, cause and effect, and argument. The second premise states that students can master any writing task put before them if they are practiced in the rules and conventions of these various modes of discourse. The classification of discourse into different categories or "modes" has provided teachers with a way of talking about writing since Aristotle first classified types of discourse. Modes of discourse pedagogy was the preferred way of teaching writing from late in the nineteenth century, well into the 1960s, when it was displaced by process pedagogy. Process theorists attacked modes of discourse pedagogy on the following grounds: 1. Modes of discourse pedagogy focuses on the models for rather than on the purposes of discourse; 2. Modes of discourse pedagogy places form above content, thereby neglecting the development of students' critical thinking skills; 3. Modes of discourse pedagogy ignores the process of writing, providing no instruction in the invention, drafting, and revision processes. While some teachers of modes of discourse pedagogy do indeed neglect the purposes and processes of writing, the above charges are not entirely fair. Modes of discourse pedagogy, when properly understood and employed, involves more than simply teaching various models for organizing papers. Rather, the pedagogy addresses all aspects of the thinking and writing processes. Consider, for example, that modes of discourse pedagogy can be used as Aristotle first suggested they be used - that is, as a way to help students to determine or focus their topics. More important, however, is that modes of discourse instruction can be used to lead students systematically through a hierarchical system of cognitive functions. In these classrooms, professors develop assignments that progress through the modes, moving students from the personal narrative to the analytical argument, and from simple organizational strategies that are chronological and/or spatial, to more complex organizational strategies that are more formally logical. In this way, modes of discourse instruction sharpens students' critical and analytical skills. One additional benefit of modes of discourse instruction: this pedagogy is useful in courses throughout the disciplines. Professors who teach courses in history, geography, and psychology can determine ways that modes of discourse assignments might be made to work in their classrooms. For example, professors in the sciences and social sciences might first require students to describe a behavior or phenomenon, then to explore its causes and effects, and finally to build an argument about that phenomenon. This progression of assignments works extremely well in disciplines that are explicitly concerned with the collection and evaluation of evidence. As students move through this sequence of assignments, they will improve their thinking and their writing skills. EXAMPLE: WILLIAM SPENGEMANN'S WRITING 5 William Spengemann believes that the primary difficulty in teaching first-year writing courses is moving young writers from narrative (with which they are generally comfortable) to exposition (which they find difficult). To accomplish this aim, Professor Spengemann takes students through a sequence of rhetorical modes, beginning with narrative and ending with argument. As they move through the assignments, students learn to rely less and less on chronological organization and to organize their essays logically. Professor Spengemann uses one book, Paradise Lost, as the basis for eight assignments: Narrative: Students are asked to recount the history of the world according to the "arguments" that precede each book of Paradise Lost. To complete this assignment, students must extract the information they need and arrange it chronologically to explain the history of the fall of Adam and Eve. Note that this narrative is not a personal story but is entirely text-based. Still, it requires students to tell a story - something that they are generally comfortable doing. Description: Students are asked to describe Hell or Paradise so as to convey some single idea. Students have to consider how to arrange their description so that every detail serves that one idea. Combination of Narration and Description:Students are asked to narrate Satan's flight from Hell to Paradise as Satan experiences it. This assignment raises the questions of position and point of view: Where is Satan when he tells his story? When does Satan tell his story? Years after his adventure? Or just after? How do these choices influence point of view? And how does point of view then influence the entire story? Students are clearly being asked to consider questions appropriate not only to narrative, but to analysis as well. Process Analysis:Students are asked in this assignment to describe the creation of the world. Process analysis is considered the first of the four expository forms in that it still relies on chronology as an organizing principle. However, process analysis carries students one step beyond narrative in that they must consider the ways in which motive, intention, plan, agents, tools, materials, and procedures condition one another and conspire to determine the product. Cause and Effect:Students are asked to consider and then to describe the immediate consequences of "the fall." In this assignment, students consider not only what happens, but why those things happen, and how certain actions lead logically to certain consequences. Comparison and Contrast: Students are invited to compare any two of the following characters: Adam, Eve, Satan, and The Son. Here the comfort of the narrative form has vanished completely; students must seek out logical ways of organizing their observations regarding the characters being compared. Definition: Students are asked to define freedom in Paradise Lost. Throughout their reading, students will have been collecting passages concerning freedom. Now they must abstract from these passages a single definition of freedom that will accommodate them all. The task of organization here is purely expository. Argument: As their final assignment, students construct an argument for or against the use of Paradise Lost in Writing 5, using the techniques of narrative, description, and exposition they have learned in order to make their case reasonable, authoritative, and persuasive. EXAMPLE: MARY DESJARDINS' "FILM AND FEMALE AUTHORSHIP" COURSE We found a good example of how modes of discourse pedagogy is used to develop critical thinking skills in Mary Desjardins' First-Year Seminar, "Film and Female Authorship: American Women Directors." In this course, the writing assignments are designed, using clear and elaborate prompts, to lead students through increasingly complex critical thinking skills. Each assignment asks students to compare and contrast texts - but in each assignment, the exercise requires students to operate upon texts in increasingly sophisticated ways. In her first writing assignment, Professor Desjardins asks her students to write a fourpage paper that compares and contrasts the way two films - Clueless and The Blot "construct a relationship between the ideas of femininity and consumerism." Her prompt for this paper goes on to give the students writing advice - for example, to restrict the discussion of the movies to one or two scenes, and to be sure to use clear and specific examples. She also provides a series of questions to help students to develop their arguments. It's interesting to note that each of these questions begins by asking, "What kinds...?" "What kinds of ideals about femininity do the female characters in each film represent?" "What kinds of attitudes do you think each film has towards certain ideals of femininity?" These questions belong to the Division and Classification mode of discourse - a level of critical thinking more sophisticated than narration and description, but not as sophisticated as argument or analysis. In short, Professor Desjardins is requiring a compare and contrast essay that asks her students to collect and then to compare observations, but that doesn't yet require students to create sophisticated academic arguments. In her second assignment, Professor Desjardins presents her students with a more difficult problem. She provides students with articles from magazines, newspapers, and various academic journals and then asks them to consider "how contemporary women film directors have been 'constructed' as authorial agents in various print-media outlets." In this assignment, too, students are asked to compare and contrast, but this time the comparisons are multi-leveled and more complex. For example, Professor Desjardins asks students to draw comparisons between the perception of women directors, past and present. In particular, she asks them to pay attention to differences and similarities in how women directors are talked about in different magazines (Ms., for example, as opposed to Time). She also asks students to consider any differences that might exist between how a woman director attempts to construct her own identity or media persona, and how this persona is being constructed by the media. In this exercise, Professor Desjardins is using compare and contrast not only to move students to make sharper observations about a text, but to move them to understand text in context. It is interesting to note that in this assignment, instead of offering specific writing advice, Professor Desjardins outlines a source requirement: students must talk about at least three media outlets and must refer to at least three journal articles. This requirement also seems aimed at moving the students to contextualize both what they've read and what they've decided to write about. While the first assignment helps students to sharpen their observations, and the second leads them to understand how to contextualize what they are reading, the third assignment moves students to consider the course's big question: Do the "marks of female authorship" reside in an artist's work, or are they constructed by her audience? The prompt for this writing assignment carefully brings students to this question by asking them first to choose two films by a contemporary woman director to compare and contrast. The assignment then instructs them to contextualize the work. So far, the students are on familiar ground. Next, however, Professor Desjardins moves the students to the heart of analysis by asking them to look for patterns or trends within a particular director's work, and then to consider if the director's work can be comfortably categorized within the limits of an existing genre. Once the students have done this analysis, they are ready to take on the "big question." They can also start to consider whether or not the works of the director they have chosen will argue for or against the notion of a particularly female form of authorship. In her fourth and last assignment, Professor Desjardins does not provide her students with a prompt. Instead, students must discover their own topics. Professor Desjardins hopes that the critical reading and thinking skills that the students have developed throughout their first three projects will prepare them to find, narrow, sustain, and support a topic that is academically appropriate and interesting.