Running Head: Power and Its Effect on Culture and Leadership

advertisement

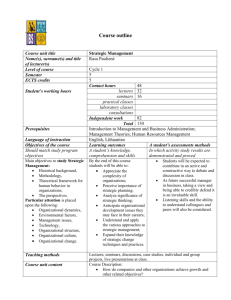

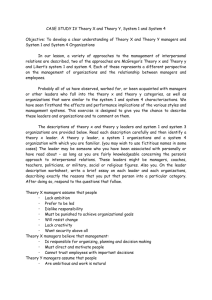

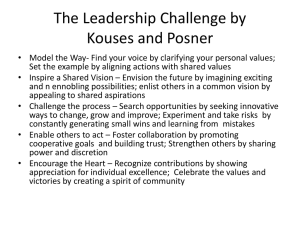

Power and Culture 1 Running Head: Power and Its Effect on Culture and Leadership Power and Its Effect on Culture and Leadership EAD625 Linda Schmitigal Power and Culture 2 Power and Its Effect on Culture and Leadership The affect of power on leadership and culture is real and this affect can be long lasting. The term power conjures up images of both good and evil and is a topic that is rarely discussed in leadership training or management planning sessions. But, because “power is the foundation for influence attempts” (Johnson, 2001, p. 10) understanding its uses and limitations helps a leader to learn to use it effectively. Becoming an effective leader is critical because organizations do not form accidentally. Leaders help organizations form culture by “being goal oriented, having specific purpose, and are created because one or more individuals perceive that the coordinated and concerted action of a number of people can accomplish something that individual action cannot” (Schein, 2004, p. 226). Because of the importance of the power variable to leadership and cultural development, this paper will look at how leaders use or abuse power and the affect this use of power has on the culture of an organization. Culture The culture of an organization consists of shared beliefs, values, and assumptions (Schein, 2004). The leader exerts tremendous influence on development, orientation, and continuation of an organization’s culture (Schein, 2004). The influence of leaders on the organization is so great that two similar companies, in the same industry will have different shared beliefs, values, and assumptions. Therefore, successful leaders pay attention to the rites and artifacts of an organization’s culture and works to either continue the culture if it is working well or change the it to better meet the needs of the organization (Schein, 2004). Power and Culture 3 Definition of Power The literature is rife with descriptions of power and how people attain power. An early description of power comes from French and Raven (1959). These researchers defined power and categorized it into the following five sources: Coercive Power is derived from authority to impose penalties or punishment such as physical force, salary reduction, or student suspension. Reward Power is the authority to deliver something of value to others such as trust, praise or cooperation. Legitimate Power resides in a position, not a person, but gives the person the right to control employees’ behavior. Expert Power is based on a person’s knowledge, skills, education and certification. Referent (Role Model) Power is based on the admiration one individual has for another. (p. 11) “Leaders typically draw on more than one of these power sources” (Johnson, 2001, p 12). As different situations arise, different leadership roles may require the use of different power sources. However, Johnson (2001) states, “U.S. workers are more satisfied and productive when leaders rely on forms of power that are tied to the person such as expert and referent power” (p. 12). And, though coercive power may create quick results, it becomes less effective over time (Johnson, 2001). Therefore, an important leadership and cultural consideration must be made of the type of power that a leader uses and it must be grounded in the observation that people don’t leave organizations, they leave managers Power and Culture 4 (Kouzes and Posner, 2002). Leaders must recognize that employees are aware of power and how they relate to the person in power (Johnson, 2001). Other researchers have written how power relationships affect subordinates in an organization. The next two power examples demonstrate how followers give power to managers and how relationships within a company can bestow power. Griffin (1999) writes about two power principles: belief and fear. Power Principle #1 is Belief which is based on the employee’s understanding that he or she is being supervised. This belief is based on the employment compact or the relationship between employee and supervisor, and it requires the acquiescence of power by the employee. Power Principle #2 is Fear which is coercive and is manipulated by the supervisor. Griffin (1999) writes “the starting point in the equation is the strategic or planned use of space into which the employee is placed” (p. 13). This space is organized so that is produces a two-way and unbalanced flow of information in which the supervisor controls the content and the amount of knowledge the employee knows. Griffin (1999) also suggests that these two forms of power, belief and fear, should not be visible or extreme because, though compliance will be the result, high productivity or staff retention will not be sustainable. In addition, surveys of manager trainees found that it is power that drives many executives and that motivates them for executive activity (Griffin, 1999). In conclusion, this theory reinforces power and the wielding of power as strategies which leaders within an organization can use to control subordinates. Another researcher describes yet another form of attaining power and that is by association. This is a much more nebulous form of power attainment yet according to Kleiner (2003), occurs often within organizations. Kleiner (2003) describes this type of Power and Culture 5 associative power as the belonging to a core group of people who are respected, popular, successful, manipulative, or control access to information. These core people can exert tremendous power within an organization and leaders must recognize their power (values, beliefs, and attitudes) and work with this group. Kleiner (2003) describes that how this group attains its power is not through the power of their individual positions, but because other people within the organization have conferred power upon them. Kleiner (2002) defines this as “amplification which is the process by which a core group member’s remarks, actions, and even body language are automatically magnified by his followers” (p. 91). In addition, he describes this type of core leadership as “the ability to get others to confer legitimacy on us—and thus to get others to put us in the core group” (p. 89). Smart leaders within this group also recognize that this legitimacy requires deliberate attention and design and significant work. An effective leader, therefore, must discover if a core group exists in an organization, and if so, who is in the membership. Working against this group’s values and beliefs would be counterproductive (Kleiner, 2003). So far, we’ve described power as it relates to individuals and how they obtain it, and power as it relates to employers and its effect on employees. The next section will look at personal power. Personal Power Is the quest for power something that everyone works to attain? Many researchers write that attaining power can be used as a measure of our success and a means to furthering that success (Griffin, 1999, Kramer, 2003). Whether power is attained through personal power sources (French and Raven, 1959), through belief and fear (Griffin, Power and Culture 6 1999), or association (Kleiner, 2003), how a person conducts oneself can convey the presence of power. A very simple way to convey personal power is by the way one behaves. “One communicates a sense of personal power by developing authority, accessibility, assertiveness, a positive image, and solid communication skills” (Haddock, 2005, p. 13). Haddock (2005) explains each of these items as follows: Authority requires a trust in one’s own skills and abilities An assertive person wins by influencing, listening, and negotiating so that others choose to cooperate willingly. Accessibility requires networking which increases one’s visibility and gives a person a valuable circle of people to give and receive support and information. Image is created by standing tall, walking proudly, acting confidently, and clearly stating who and what one does. Communication style conveys power by speaking and enunciating clearly, avoiding slang, jargon, and vocal hesitations, and writing clearly and succinctly. (p. 13) Though these may sound simple, following these guidelines can help a person attain some amount of personal power, closely related to referent power. And, acting powerfully is seen as a desirable trait in many organizations (Kramer, 2003). Positive Benefits of Power Kouzes and Posner (2002) writes that to get power, a leader must give power away and share power with subordinates which results in higher job fulfillment and performance. Hence, power can play a positive role in the culture of an organization. An Power and Culture 7 effective leader who influences the culture of the organization must possess a high need for power motivation and a desire to be impactful and influential (McClelland and Burnham, 2003). The need for power, however, must be disciplined and controlled so that the leader works toward the benefit of the institution and not to better one self (explained in more detail in a later section). McClelland and Burnham (2003) states “a good manager is one who, among other things, helps subordinates feel strong and responsible, rewards them properly for good performance, and sees that things are organized so that subordinates feel they know what they should be doing” (p. 120). Other characteristics successful and powerful managers possess include low affiliation motivation (willingness to please) and high inhibition (McClelland and Burnham, 2003). In addition, leaders must be aware of how the messages they both consciously and unconsciously send are interpreted and how these messages impact the receiver (Kleiner, 2003). Leaders, who lead through power which enable subordinates to do their jobs and have control over aspects of those jobs, liberate these subordinates to perform their very best and create opportunities for the organization, employees and clients (Kouzes and Posner, 2002). Good to Great Leaders. Using the positive uses of power, Collins (2001) described characteristics of leaders who took their organizations from good performance to great performance. He emphasizes the importance to organizations of putting people in positions of power having the right characteristics and attributes. Here are a few of the characteristics of great leaders according to Collins (2001): Get the right people on the bus and into the right seats, and move the wrong people off the bus. Power and Culture 8 Confront the difficult facts of the current situation, yet simultaneously focus on where the company is heading. Use the flywheel concept that requires the leader to keep pushing a project until the breakthrough point and momentum begins. Follow the hedgehog concept which requires the leader to focus on one thing only and do that one thing well. Use technology carefully and invest heavily only when it is tied to the hedgehog concept. Create a culture of discipline--disciplined people, disciplined thought, and disciplined action. Each of these characteristics and actions require a leader with resolute will and the influential power to accomplish each action. A leader, who is not focused on the good of the organization and who is without humility or force of will, cannot move an organization in any direction (Collins, 2001). To sum up the positive benefits of personal power, McClelland and Burnham (2003) state “the manager’s concern for power should be socialized—controlled so that the institution as a whole, not only the individual, benefits” (p. 126). Great leaders use their power in ways that garner respect from subordinates and motivate others to work for the good of the organization (Kouzes and Posner, 2002). Positive use of personal power of managers and subordinates, therefore, helps an organization successfully accomplish its mission and goals. Power and Culture 9 Negative Consequences of Power Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely (Acton, 1887). This is the negative consequence of power; some people do not know how to handle power when placed in a position that gives them the power they have worked so hard to attain. When power is abused by a leader or manager, research shows that employees may become confused, uncertain, unable to complete tasks, and become prone to wasting time and energy talking about or complaining about the organization (Gunn, 2004). Collins (2001) writes that some people will never be great leaders because attaining the position of power is all about the fame, fortune, and adulation that come with the position. Kramer (2003) also states that “there is something about the pursuit of power that often changes people in profound ways. Indeed, to get to the apex of their profession, individuals are often forced to jettison certain attitudes and behaviors—the same attitudes and behaviors they need for survival once they get to the top” (p. 60). Some of these attitudes and behaviors that get jettisoned include being generous with praise, quick to recognize others’ achievement, and self-effacing about one’s own accomplishments (Kramer, 2003). Some additional symptoms of reckless leadership that can lead to the abuse of power include the following: The leader loses sight of the big picture and spends more time staving off imminent disaster. The leader does not listen to dissenting voices or warnings of doom or disaster. The leader enlists the trust and advice of a confidant fending off isolation and insulation. Power and Culture 10 The leader is in danger of suffering from illusions of grandeur The leader becomes greedy and the relentless, competitive quest for power and status becomes and end in itself. The leader fails to stop and evaluate the path both of the organization and of oneself as well. (Kramer, 2003, p. 65) According to Kouzes and Posner (2002), “it’s fun to be a leader, gratifying to have influence, and exhilarating to have scores of people cheering your every word. In many all-too-subtle ways, it is easy to be seduced by power and importance” (p. 396). The effect of abusive power on the culture of an organization is negative and creates low motivation, unhappy employees, and low productivity (Kouzes and Posner, 2002). In addition, if negative power of individuals or groups is acknowledged and rewarded in an organization, deceit, inefficiency, moral cowardice, and general unaccountability can be sanctioned. “The core group reinforces whatever it pays attention to” (Kleiner, 2003, p. 89) no matter the ethical considerations or outcomes. Negative use of power creates low production and motivation, a culture that becomes toxic, and an organization doomed to lack greatness. Yet, many leaders believe that “power is a fixed sum: if I have more, then you have less” (Kouzes and Posner, 2002, p. 285) thus defeating the premise that leaders inspire subordinates to do great things and that by giving away power, the leader gains power (Kouzes and Posner, 2002). In concluding this section about the negative abuse of power, the importance of leadership training must not be overlooked. The development of leaders will fail if administrators approach the training process with control, ownership, and power-oriented Power and Culture 11 mind-sets rather than reinforcing the need for leader to share accountability (Ready and Conger, 2003). Conclusion Power, as a leadership trait, affects not only the leaders and employees who wield it, but it also affects subordinates and followers who benefit or suffer from the wielding of power. Leaders must recognize the temptation that power leads to and how it affects their leadership ability, and more importantly, how it affects the people around them. As this research shows, power is an important leadership trait that when used properly, creates and maintains a productive work culture. Positive, humble use of power empowers and motivates employees and improves the greatness of an organization. “It creates a positive work environment, allowing staff to focus on the job at hand without distraction—no lost productivity due to gossiping or to conflict between individual needs and those of the institution” (Gunn, 2004, p.3). The job of educational leaders is to help prepare upcoming leaders and to encourage them to become aware of the effects that success and power might have on their behavior, and consequently, the culture of an organization. Additionally, discussing power and constructive uses of power must be done. Without frank discussion of the evils of power, many leaders and organizations are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past and to create leaders who become power mongers (Kramer, 2003). Power and Culture 12 References Acton, L. (1887). Personal correspondence to Bishop Mandell Creighton. Collins, J. (2001). Level 5 leadership: The triumph of humility and fierce resolve. In Best of HBR: Harvard Business Review, (2005, July-August). 136-146. French, R. P. & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed)., Studies in social power (pp. 150-167). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Griffin, G. R. (1999). The power game: How to use the black art of corporate and personal power to get the results you want. Oxford Capstone Publishing Ltd. Gunn, B. (2004, August). Does power corrupt? Strategic Finance. 86(2), 2. Haddock, P. (2005). Communicating personal power. Supervision. 66(11), 13. Johnson, C. E. (2001). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership: Casting light or shadow. Sage Publication, Inc. Kleiner, A. (2003, July). Are you in with the in crowd? Harvard Business Review, 86-92. Kouzes, J. M. and Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Kramer, R. M. (2003, October). The harder they fall. Harvard Business Review, 58-66. McClelland, D. C. and Burnham, D. H. (2003, January). Power is the great motivator. Harvard Business Review. 117-126. Ready, D. A. and Conger J. A. (2003, Spring). Why leadership-development efforts fail. MIT Sloan Management Review. 44(3). Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.