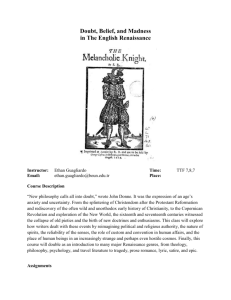

Spenser`s muse and savior

advertisement

Jack W. Ward May 12, 2000 English 54 Dr. Jessica Wolfe Spenser’s Muse, Savior and Allegory in the “The Shepheardes Calender” and “The Faerie Queene” In Book 1 of the “Faerie Queene,” Edmund Spenser describes a complex anatomy of salvation in which free will might have some power to aide or hinder a predestined soul. Despite Red Cross Knight’s trials, Una and the narrator assure the reader and the knight that he cannot fail in his quest, and guarantee his salvation. Regardless, Spenser still tries Red Cross Knight and explicitly illustrates the possibility of failure with Red Cross Knight’s near suicide attempt in Despair’s cave. Spenser suggests that, like the soul’s state of salvation or damnation, the poet requires no small degree of grace in his vocation, and just as the as the individual might have effect on his soul, so too, the poet’s labor co-determines his success. Throughout “The Shepheardes Calander,” Spenser struggles with the nature and source of poetic wit as part of his attempt to determine the Protestant poet's place and identity in the poetic tradition. In “October,” Spenser develops a complex relationship between divine inspiration and human labor that implies a symbiotic relationship between the muse and the poet, each feeding off of each to advance poetry. Like his complicated and seemingly contradictory view of salvation, Spenser’s view on poetics requires both providence, in the form of heavenly inspiration, and free will, in the guise of labor, to produce successful poetry. In his proems to the “Faerie Queene,” Spenser characterizes his muse, the personification of heavenly inspiration, with both pagan convention and Christian imagery. He reveals, in these proems a distinctly Protestant relationship with his muse, who, like many of the characters in the allegory, is both a figure and a state of being. Throughout his poetical works, Spenser develops a working definition of salvation that allows room for human agency and divine providence without anatomizing these parts. This description of salvation, while complete for Spenser, with the subtleties intact, is complicated for the reader, being wrought with ambiguity. Spenser’s theology of salvation in “The Faerie Queene” attempts to reconcile free will and predestination as Red Cross Knight is simultaneously assured of his salvation and tried. To rescue him from Despair’s rhetoric, Una reminds Red Cross Knight of his predestined success: “Ne let vaine words bewitch thy manly hart,/ Ne develish thoughts dismay thy constant spright./ In heavenly mercies hast thou not a part?” (I, 9, 53.4). In reminding the knight of his certain salvation Una is also reminding him to have faith. The disparity between the certainty of Red Cross Knight’s salvation and his nearness to committing unpardonable sin suggests an uncertainty about the nature of salvation. While Red Cross Knight is assured of his success, he is given ample opportunity to fail. Spenser seems to suggest that although one might be ordained to heaven or hell, one might lose or gain grace by vice or virtue. This idea of grace dependent upon virtue appears again with Heavenly Contemplation who says there are “[God’s] chosen people purged from sin and guilt,” who will live in the “New Hierusalem” after death (I, 10, 57.4). Heavenly Contemplation says Red Cross Knight is of those chosen since Hierusalem “is for [him] ordained a blessed end” (I, 10, 61.5), yet the knight must study under Heavenly Contemplation and repent for his sins with great pain. In effect Red Cross Knight is regaining his virtue that he partially lost at the hands of Duessa and Despair by works of human agency. Like his ambiguous theology of salvation, Spenser’s views on poetry paradoxically require both labor and divine ordination. In the Argument preceding October, Spenser calls poetry so worthy and commendable an arte: or rather no arte, but a divine gift and heavenly instinct not to be gotten by laboure and learning, but adorned with both, and poured into the witte by a certain [enthousiasmos]” (418). The “enthusiasmos” is not only a kind of poetic inspiration but that of a religious nature, by one of the possible definition. As such, the divine gift is an inspiration that is linked to God. Spenser first calls poetry an art in this quotation and then corrects himself as if he were improvising a speech. For an author to include what he has negated gives considerable emphasis, not only to the correction, but to the mistake itself. Spenser makes a conscious decision to correct himself in front of his audience rather than to rewrite the passage. In doing so the argument suggests a paradoxical qualification of poetic wit’s nature, by which, like Red Cross Knight’s success in the “Faerie Queene,” the poet's wit and career are determined and ensured yet simultaneously effected by his endeavor. Poetry might only be divinely inspired but man can effect it with his labor. The muse’s importance to poetry is evident in writings as early as Homer but Spenser’s emphasis on the “divine gift” (418) in the Argument all but eliminates human endeavor from the process. This deference to God’s providence for poetic creation smacks of Protestantism. It is as if, like one’s salvation, God predetermines the poet’s level of success, and that heaven is supplying him with his matter. But like his treatment of predestination in “The Faerie Queene,” Spenser’s treatment of poetic origins in “The Shepheardes Calender” gets complicated by the degree of free will that seems to operate along side and simultaneously with providence. In “A Letter of the Authors” prefacing “The Faerie Queene,” Spenser states his imitation of the classical poets. He says he has “followed all the antique Poets historical, first Homere, who in the persons of Agamemnon and Ulysses hath ensampled a good governour and a vertuous man, … then Virgil, whose like intention was to doe in the person of Aeneas: after him Aristo … and lately Tasso …” (1). Here, in the preface to his masterpiece, Spenser commits to the tradition of the classical poets yet “The Faerie Queene,” with its virtuous man, Arthur, and governor, Elizabeth, is as distinctly British and Protestant as Virgil’s Aenead is Roman. As an Anglican epic intending to give examples of virtue in both the private and public lives, “The Faerie Queene” defines Spenser’s idea of British Protestant virtue, just as Homer defined virtue for the Greeks. This commitmentto the classic writers, however, wavers in his stylistics as he combines pastoral conventions with the epic throughout “The Faerie Queene.” Any imitation of the Greeks and Romans Spenser makes, and even those intentional departures from tradition, imply Spenser’s labor in his poetic creation. In “October,” Cuddie emphasizes the importance of following tradition in his advancement as a poet. “Indeed the Romish Tityrus…” Cuddie reflects, Through his Mecaenas left his Oaten reede Whereon he earst had taught his flocks to feede, And laboured lands to yeild the timely eare, And eft did sing of warres and deadly dred, So as the Heavens did quake his verse to here. (55-60) To follow the example of Tityrus, whom EK notes is “Wel knowen to be Virgile” (420), is for Cuddie to follow tradition and in doing so labor to advance his poetry. This passage especially complicates the notion when put in context as a response to Piers. In line 43 and 44 Piers suggests that switching to a higher genre may entice Cuddie’s “Muse [to] display her fluttryng wing,/ And stretch her selfe at large from East to West." Cuddie’s traditional labor is a means of attaining the “divine gift and heavenly instinct” described in the argument. The poet must have divine inspiration, and he must labor to get it and retain it. This idea is a significant departure from the assertion in the Argument that says labor merely adorns divine inspiration. The apparent necessity of labor in the process of producing poetry raises human agency from a mere accessory to major part of the process. An allegorical reading of “January” supports the essential role of human labor in the poetic process. The first month finds Colin leading “forth his flock, that had bene long ypent./ So faynt they woc, and feeble in the folde,/ That now unnethes their feete could them uphold” (January 4-6). As a shepherd, Colin’s flock is his work; if the shepherd is the poet, as Spenser makes Colin, then his poesy is analogous to his flock. Colin’s sheep are so weak, his poetry so neglected, that they struggle merely to feed themselves or return to a life of exercise. Just as the flock needs exercise to survive, so does Colin’s poetic wit. By this allegorical reading, the poet must exercise his poetry to keep it strong, and he must labor to use the divine gift of God's inspiration. In discussion of Colin’s Poetry, Cuddie also refers to “peeced pyneons” which had they “bene not so in plight,” Colin might fulfill his poetic ambitions (87). Hugh Maclean’s note on this passage identifies the “peeced pyneons” as “imperfect, patched wings[,]” and EK’s glosse calls them “unperfect skill” (422). Recalling the muse’s inspiration metaphorically as her “fluttryng wing” in line 43, line 87 looks like a rebuttal to the importance of the muse, using a similar winged metaphor. While Spenser spends a great deal of “October” and “January” focusing on the importance of human agency, his assertion that poetry is “no arte, but a divine gift and heavenly instinct not to be gotten by labour and learning, but adorned with both” continues to remain significant in determining the source of poetic wit (417). Throughout “The Shepheardes Calender” the speakers struggle with poetic labor and the nature of the muse, trying to figure the source of their poetry. Both labor and divine inspiration appear to be necessary to poetry in “The Shepheardes Calender” and interrelated in their effects. The reconciliation of the two is like a “heavenly instinct” that is bestowed by God and predisposition’s one towards poetry. This “heavenly instinct” does not predestine the poet; like any instinct neglected of exercise, it will atrophy, just as a house cat’s hunting instinct is considerably dulls after years of comfort. So by the “divine gift” and continuous labor may the poet produce good poetry, and promote himself to higher genres. The symbiotic relationship between the muse and the poet that appears in “The Shepheardes Calender” continues in Spenser’s Commendatory Verse “To the Learned Shepheard.” In the first stanza the speaker addresses the poet and gives a kind of technical schematic for the interaction between the poet and the muse: Collyn I see by thy new taken taske, since sacred fury hath enricht thy braynes, That leades thy muse in haughty verse to mask, and loath the layes that longs to lowly swaynes. That lifts thy notes from Shepheardes unto kings, So like the lively Larke that mounting singes. (To the Learned Shepheard 1-5) Collyn has taken up his new task because of the “sacred fury hath enricht [his] braynes” suggesting that he has been inspired by some greater being to take up the new task seemingly removing the power to create from the poet and ascribing to inspiration. However, in the next line the power of human agency is restored. It is this “new taken taske” that instigates the muse to aide him in his endeavor. Spenser’s speaker proposes that the poet needs some “sacred fury” to advance, and that the poet must advance to court the muse to joining his cause. The sacred fury might as well be inspiration effecting the braynes but sacred suggests a divine, heavenly quality that this passage implies the muse lacks. The muse, generally characterized as that which proposes poetry to the poet, is led, in this passage, by human endeavor inspired by divine assistence. As characterized here, the muse is much like salvation: it is ordained by the grace of God but must be pursued to retain, advance and maintain it. The salvation and inspiration connection is supported in the same poem when Spenser connects Collyn, the poet, and Red Cross Knight and their successes in their respective crafts. After illustrating Collyn’s success, Spenser says, So mought thy Redcrosse knight with happy hand victorious be in that faire Ilands right: (To the Learned Shepheard 25-26). The reader knows that just as Red Cross Knight’s victory in battle is assured throughout the “The Faerie Queene”, so is his salvation because Spenser writes the two as nearly synonymous in the work. Spenser makes the connection between the success of the poet and the success of Red Cross Knight obvious in this quotation, and in doing so reveals the correspondence between poetic inspiration and salvation. In the production of poetry, labor is essentially poetic virtue, while the divine gift is equivalent if not identical to grace or God’s providence. The “heavenly instinct,” then is analogous to salvation. The nature of poetic origins as described in “The Shepheardes Calandar” is a kind of symbiotic relationship between the muse and the poet in which one needs the other for either to be fully realized. The descriptions and incantations of the Muse in “The Faerie Queene” suggest a relationship between the poet and the muse much more like that of the Protestant and God. In the proems to the first and sixth books of “The Faerie Queene” Spenser gives invocations to his muse that characterize it and his relationship to it. Spenser calls his muse “Ye sacred imps, that on Parnasso dwell,/ And there the keeping have of learnings threasures,” (VI, Proem, 2.2-3). These imps on Parnassus are the classical muses who aide pagan poets like homer and Virgil throughout their writings. Similarly, in the proem to Book I, Spenser implies that cupid and Venus, Greek gods and classical symbols of love, might succor his art. These, as a great many more references, illustrate Spenser’s muse as identical to those classical muses, but Spenser complicates this idea throughout his work. In the second stanza of the Proem to book 1 Spenser refers to the muse as the “holy Virgin chiefe of nine,” (I, Proem, 2.1). Spenser befuddles the nature of the muse by referring to her as Calliope, chief of the nine muses that sit on Parnassus, but also as a “holy virgin.” Spenser suggests that, As a holy virgin, the muse has Christian virtue or even a degree of divinity. The Holy Virgin Mary, while a catholic symbol, was touched by some divine breath with her immaculate conception and birth of Christ, and neoplatonic ideals of the era would suggest that a virtuous and beautiful lady might inspire a man to climb toward his salvation or in this case art. This idea of the muse as a Christian figure is not limited to this line as the Commendatory Verse “To The Learned Shephearde” has suggested. More convincing then the language that describes the muse is Spenser’s interaction with the muse. In his incantation prefacing the cantos of Book I Spenser reveals a subservience to and piety before his muse, as if it were his savior or God. Spenser admits that …[He] the man, whose Muse whilome did maske, As time her taught in lowly Shepheards weeds, [Is] now enforst a far unfitter taske, For trumpets sterne to chaunge mine Oaten reeds…(1.1-4) In this admission, the reader can see that the poet is at the will of his muse. He is compelled to change genres before he feels he is ready because the muse has changed his oaten reed, a tool of the pastoral, to a trumpet, a tool of epic. Spenser shows that the ability to climb to higher genres completely dependent on the muse, who, by inspiration raises the poets level. The poet is a vehicle that carries out the will of the muse. Spenser explicates on this suggestion in stanza 2 of the proem of book I when he asks “Helpe then…/ Thy weaker Novice t performe thy will,/ Lay forth out of thine everlasting scryne/ The antique rolles, which there lye hidden still…” (1-4). These lines point to partnership between the muse and the poet in which the Muse “proposes and the poet disposes” (Wolfe). That is to say that the poet writes for man what has always been written in Heaven and in effect carries out the will of the muse, acting as little more than a agent. This interaction between muse and poet is strikingly similar to that of the Protestant and the savior. The poet is graced by the muse, just as the Christian is by God, and carries out the muse’s will as a result. The true christianity of the relationship is the poet’s desire to carry out this will. In the second stanza Spenser asks the muse to help him carry out her will. The way in which the poet asks the muse for help deepens the likeness of the muse/poet relationship to the Protestant’s relationship to God. Throughout the proem to the first book of “The Faerie Queene” Spenser asks for assistance because he is “too” lacking of something or “too” flawed in some way. He calls himself a “Novice” in stanza 2 and asks for help for his “weake wit,” and asks the muse to “sharpen [his] dull tong” (2.2,9). Similarly in the fourth stanza he asks the muse to “shed thy faire beems into my feeble eyne,/ And raise my thoughts too humble and too vile…” (4.5-6). This intimation of unworthiness and fallibility parallels Calvinist doctrine that says only through the grace of God might human beings, vile and wicked by nature, attain any degree of perfection and rise above their flawed status. The incantation of the muse in Book I expresses an analogous sentiment: without the poetic grace of the muse, the poet is incapable of creating poetry, carrying out the will of the muse or advancing genres. As a result the muse is a savior of sorts if not an allegorical representation of the savior God. The different descriptions of the muse are, to a great extent, reconciled in canto 10 of Book I when Heavenly contemplation takes Red Cross Knight to his mountain that is described as “Such one, as that same mighty man of God,/… Dwelt fortie dayes upon; where writ in stone/ With bloody letters by the hand of God,” or “like that pleasaunt Mount, that is for ay/ Through famous Poets verse each where renownd,/ On which the thrice three learned ladies play” (I, 10, 53,54). In both passages the mountain is a place where divine inspiration resides. In the first it is inspiration from God himself as the Ten Commandments were written in “bloody letters by the hand of God,” while in the second passage the mountain is the seat of the classical pagan muses, Parnassus. By explicitly describing the same mountain as both the location of Christian inspiration and pagan inspiration suggests that the two are not necessarily distinct sources of inspiration but identical. If they are in fact distinct sources they are close enough to one another that one might be represented as the other without significant loss of characteristic. “The Faerie Queene” supports this explanation where the pagan representation of the muse is merely a figure allegorically signifying the divine inspiration of God’s Grace. Edmund Spenser’s muse, as represented in “The Shepheardes Calander,” the commendatory verse “To the Learned Shepheard” and “The Faerie Queene,” is synonymous if not identical to the savior of his soteriology. Despite any description of the muse as the pagan embodiments of inspiration, the interaction between the muse and the poet is too similar to that of the Protestant and God to suggest that the muse might be anything other than Spenser’s God. The divine nature of Spencer’s muse then elevates his poetry to God’s work and his wit the tool by which to execute it.