prescribed minimum benefits codes and relative value units

advertisement

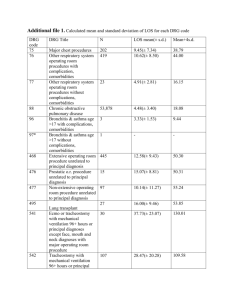

PRESCRIBED MINIMUM BENEFITS CODES AND RELATIVE VALUE UNITS Abt Associates South Africa Inc. 16th Floor, the Forum 2 Maude St Sandton 2146 Tel : 011-883-7547 Fax: 011-883-6790 E-mail : neil_soderlund@abtassoc.co.za Report prepared for the Board of Healthcare Funders by Dr Neil Söderlund Dr Shaun Conway Abt Associates Inc Contents 1. INTERPRETATION OF DATABASE ...................................................................................... 3 2. INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE OF THE DATABASE: ................................................................ 5 3. RELATIVE VALUE UNITS (RVUS) AND THE SUITABILITY OF MINIMUM BENEFITS CODES FOR REIMBURSEMENT PURPOSES............................................................ 6 3.1 CALCULATING RVUS ................................................................................................................. 6 3.2 RESOURCE PREDICTIVE POWER ................................................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Data sources ..................................................................................................................... 7 3.2.2 Statistical methods ............................................................................................................ 7 3.2.3 Results............................................................................................................................... 9 3.2.4 Conclusions ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................ 11 1. Interpretation of database The recently published Schedule of Prescribed Minimum Benefits requires that all Medical Schemes provide for a set of cost-effective and urgently required medical interventions. Although these are listed as approximately 300 categories in the regulations, there is in many cases, not sufficient detail to accurately map these categories onto routine health information systems for the purposes of preauthorisation, product pricing, and retrospective review. Furthermore, the schedule gives no information on the additional 300 or so categories which contain cases excluded from the schedule. Consequently, the Board of Healthcare Funders has commissioned Abt Associates to translate the Minimum Benefits Schedule (MBS) into coded format for ease of identification of included and excluded diagnoses. For each minimum benefit category (both those included in the schedule, and those considered, but excluded from the schedule), the following are provided: 1. The Minimum Benefit Code, diagnosis, and treatment descriptions for each Minimum Benefits Category (MBC) and body system chapter within which it is located. 2. Whether or not the MBC concerned is included in the Minimum Benefits Schedule. 3. ICD-10 diagnosis codes that map to the MBC. This is a many-to-many mapping. Only valid primary diagnosis codes were considered, thus excluding most ‘external cause’, ‘tumour morpology’ and ‘reason for treatment’ codes (i.e. ‘U’ to ‘Z’ codes). 4. Surgical procedure codes (CPT-4 and Gazette codes) that would be appropriate for each MBC. This is a many-to-many mapping. 5. Special procedures of a non-surgical nature that are specifically detailed in the MBS - mapped to MBC. 6. A free text field noting additional factors that may need to be considered in assessing whether a diagnosis is covered by the MBS or not. 7. Relative Value Units for each MBC (one-to-one mapping). Not all diagnoses within ICD-10 could be mapped to a MBC. Consequently two catch-all categories were included: 991Z - MISCELLANEOUS EXCLUDED - diagnoses were allocated to this category under the following conditions : 1. A number of additional categories were necessary to categorise all ICD10 codes, some of which did not exist under ICD-9, and were thus not included in the original MBCs. 2. Some diagnoses within ICD-10 were deemed insufficiently specific to be allocated to the primary field. For example, the ICD-10 code: S899 UNSPECIFIED INJURY OF LOWER LEG was considered insufficiently specific to justify mandatory coverage. Consequently, many of the ‘.....UNSPECIFIED’ or ‘.....CLASSIFIED ELSEWHERE’ diagnoses are allocated to this category. In other cases, they describe a symptom or the result of a laboratory test, rather than a diagnosis eg. HEADACHE. In these cases, an attempt should be made to get a more specific diagnosis from the attending doctor. 3. A further set of diagnoses did not map to any of the Minimum Benefit Categories, and, in the opinion of the researchers, were not severe enough to qualify for inclusion in terms of the general objectives of the MBS. 4. Some diagnoses are untreatable by definition and thus should be excluded from the package - these include all cases where the patient is already dead, and congenital abnormalities incompatible with life. 990Z - OTHER MISCELLANEOUS INCLUDED DIAGNOSES. This category includes diagnoses which are themselves not included within the minimum benefit schedule, but are typically indicative of an underlying condition which is included elsewhere in the schedule, or are sequelae of treatment for an included diagnosis. It is recommended that Medical Schemes provide cover for these conditions at least until serious underlying pathology has been ruled out. While we believe that a translation of the schedule into codes will be very valuable for funders, a number of cautions should be stated at the outset : Any coded translation of the regulations will not have the force of the regulations themselves. We have suggested a mapping of diagnosis codes to included and excluded benefits, but this will hold no force in law. Because of imprecision in medical terminology, there will never be full agreement about what is actually included or excluded in the schedule. Medical Schemes are strongly advised to apply a healthy dose of common sense to the interpretation of the schedule, and the accompanying database, and should change should change allocations of codes to categories where they deem this appropriate. In all cases, when a case is being considered for exclusion of benefit, the Gazetted Minimum Benefit Schedule should be consulted to assess the consistency of that particular case with the letter of the regulations. Although the schedule inclusions are described in terms of both diagnoses and treatment, in the vast majority of cases, assignment to a minimum benefit category (MBC) can be made solely on diagnostic information. In reality, a very wide range of interventions may be justified for a given diagnosis, and specifying all alternatives is neither possible nor useful. Furthermore, some interventions would be possible for most diagnoses. For example, almost all diagnoses might require minor interventions such as the insertion of an intravenous line, resuscitation or a chest x-ray. Where type of treatment is critical, this tends to be for the special treatments listed separately at the end of the schedule. For the remainder of cases requiring surgery, we have instead listed a set of likely surgical procedure codes derived from the original Oregon categories. These include only true surgical procedures, thus excluding generic IV insertion, x-ray, anaesthetics, etc, codes. Surgical procedure codes given are not intended to be comprehensive, and should not influence the assessment of whether or not a given diagnosis is included within the MBS or not. Both procedures and diagnoses are mapped independently onto Minimum Benefits Categories. Because a range of diagnoses are mixed together within one category, not all listed procedures will apply to every diagnosis. This is illustrated for category 950F (GIT cancers) below. While all of the listed diagnoses (to the left of the box) and procedures (to the right of the box) map to the same category, GIT cancer, a link from a given diagnosis to any of the procedures cannot be inferred. For example, a rectal resection could not be considered a reasonable procedure for cancer of the oesophagus. Oesophagectomy Oesophageal cancer. Stomach cancer Cancer of the ascending colon CANCER OF THE GIT INCLUDING OESOPHAGUS, STOMACH, BOWEL, RECTUM, ANUS, TREATABLE Rectal cancer Gastrectomy Colectomy Rectal resection The original schedule was derived from categories composed of ICD-9 procedure codes and CPT-4 diagnosis codes. The cross-map from ICD-9 to ICD-10 is only approximately 55% complete. That from CPT-4 to South African Gazette codes is even less complete1. In both cases, this is due principally to intrinsic differences between the coding systems, rather than defective cross-walks. For imperfectly mapping codes ICD-codes, an approximate best fit minimum benefits category was determined by the authors. Complete hand checking of all procedure code crosswalks to gazette codes was not undertaken because these are not required for determining whether or not a given case falls into the minimum benefits schedule. Schemes should feel free to alter these allocations if they disagree with the SAMA cross-walk used. 2. Instructions for use of the database: The database has been constructed in Microsoft Access ‘97. A startup form has been provided to allow searching on ICD10 code, diagnosis, or another field to determine whether or not a case falls within the MBS. After finding the desired diagnosis, the user should check the ‘treatment’, ‘special procedures’ and ‘other relevant information’ boxes to ascertain whether information other than diagnosis needs to be 1 The cross-walks used were obtained from The UK National Casemix Office and the South African Medical Association respectively. taken into account when determining inclusion within the MBS. The procedural information, and the RVUs shown for the category concerned are for information only and should not be treated as acceptable treatment procedures, or mandated reimbursement rates. Some diagnosis codes appear more than once in the schedule because they map to more than one MBC. These are marked as such, and the user should check all related MBCs. Many companies will wish to incorporate the tables from the access database into their own pre-authorisation or other systems. This can be done by simply extracting the relevant tables, which are labelled fairly intuitively. The Minimum Benefit Category Code is labelled ‘Newline’ in all of the tables and facilitates linking the minimum benefit schedule (INCLUSIONS) to the procedures tables (PROC, SPECIAL PROCEDURES) and the diagnoses table (DIAG_2ND). 3. Relative value units (RVUs) and the suitability of minimum benefits codes for reimbursement purposes. In many countries, state and private health insurers have adopted global, diagnosis based descriptors such as Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) for reimbursing hospitals. This approach considerably reduces the transaction costs of third party payment, and gives providers the incentives to provide care more efficiently because reimbursement is determined by the level of patient need, not the service intensity provided. With this in mind, the BHF requested that a set of relative value units be constructed which could be used to determine global reimbursement rates for hospitalisation episodes. This has been done. In addition, we have evaluated the explanatory power of the MBCs with regard to hospital resource use to assess whether they are suitable for use as reimbursement tools. 3.1 Calculating RVUs Data sources Three sources were used to estimate relative value units for MBCs: UK NHS hospital data - chosen principally because of the large sample sizes of ICD-10 coded data available. Mine hospital data South African medical scheme data - obtained from three different medical scheme administrators. All of these except one of the medical scheme sources were used during a previous exercise to determine the costs of the minimum benefit package, and their strengths and weaknesses are described elsewhere (Soderlund and Peprah, 1998). Results are presented in the database as averages of all sources so that no data can be attributed to any one source. Two RVUs are provided: An ‘overall costs’ RVU which includes hospital ward, drug, theatre, personnel (including doctors), consumables and diagnostics costs. A hospital only RVU, which includes only those costs which would be reimbursed to the hospital itself (i.e. ward, theatre, in hospital drugs and consumables). The data to calculate the ‘in-hospital’ RVU were available only from a subset of the South African Medical Schemes data, and the sample size used was thus much smaller than for the ‘overall cost’ RVU. Many of the ‘hospital only’ RVUs were calculated from sample sizes of less than 10 cases, and estimates are thus unreliable. There are also a greater number of categories for which no RVU could be calculated at all. We would thus encourage the use of overall RVUs. RVUs were calculated for each data source such that the average for a South African Medical Scheme population equalled 1. An unweighted average of the sources was then taken for each MBC. Where only one data source contributed data for an MBC, then this provided the sole RVU estimate. Data were then re-standardised to the medical scheme population. Both the hospital and the overall RVUs have a weighted average of 1. 3.2 Resource predictive power 3.2.1 Data sources A single South African medical schemes claims dataset, consisting of approximately 25000 hospital admissions, was used to assess the resource-predictive power of MBCs. 3.2.2 Statistical methods Casemix systems are designed to group together treatment episodes that would be expected to consume similar amounts of resources (or, by proxy, involve similar lengths of hospital stay). The two dependant variables under study are thus length of stay and cost. The extent to which variation in either of these variables occurs between casemix groups, rather than within them, thus determines the strength of the grouping system. Mathematically, this can be expressed as a ratio: SSBG = R2 , or the Reduction in Variance (RIV) due to the grouping SST Where: SSBG = Between groups sum of squares, or model sum of squares. SST = Total sum of squares Obviously, if n episodes are divided into n different groups, all variance will be between group, and none within group, yielding an RIV statistic of 1. It follows that the RIV statistic cannot decrease with increasing splitting of existing groups. Similarly, the chance of a random binary split reducing the variance in LOS in a sample of 10 episodes is much greater than in a sample of one hundred episodes. It thus follows that an appropriate statistic for comparison should also take into account parsimony (i.e. the number of groups) and sample size. Two commonly used statistics that reflect this preference for more parsimonious models are the F-statistic and the mean squared error (MSE): MSE = SSWG / (n-r) and, F = MSBG MSE = SSBG / (r-1)__ SSWG / (n-r) where: SSWG = Sum of squares within groups, or error sum of squares r = number of groups n = number of patient episodes Both can be considered an index of grouping efficiency given equal sample sizes. An increase in F and a decrease in MSE are associated with better model fit. RIV, MSE and F-statistics are generated by standard Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or regression routines available on most statistical software packages. A relatively small number of episodes treated may have extraordinarily long lengths of stay, and / or high costs. Most of these are not typical episodes of acute care, and there are generally non-diagnostic factors, such as family circumstances, underlying such episodes. It is difficult to distinguish such episodes on diagnostic or demographic identifiers alone, and they can only really be eliminated by excluding all cases staying longer than an arbitrary cut-off point, or costing more than a certain threshold. None of the proprietary casemix measures have been designed with the aim of predicting very long hospital stays, so appropriate trimming is essential in comparing them. Comparisons have been conducted using data after excluding episodes longer than 29 days. This trimming technique was chosen to make the results comparable with those conducted elsewhere (Soderlund et al. 1996). The aim of trimming is to remove atypical episodes from the data, and thus judge the grouping method on ‘reasonable’ data. Unfortunately, we could not compare the performance of MBCs in explaining resource use with standard casemix measurement systems because none of the routinely available systems can read procedure codes in common use in South Africa (CPT-4 or Gazette codes). The RIV statistic is comparable across different datasets and settings, however. In general, on acute hospital data trimmed at 29 days we would expect an RIV statistic for costs or length of stay in excess of 25% for a reasonable resource-classification system. Comparison data were drawn from published evidence of grouping performance of the UK HRG categorisation system (Soderlund et al. 1996) 3.2.3 Results RIV performance for MBCs is presented in Table 1 below. Table 1. RIV performance of MBCs MBCs on SA data Costs 17%* LOS 23% * total amount claimed, rather than costs UK HRG v2 grouper on UK data 25% 31% On average, MBCs are approximately 35% worse than HRGs in explaining resource use in each of their respective settings. While the performance figures are surprisingly good given that MBCs were never intended as a resource categorisation system, they are significantly worse than would be required for a valid reimbursement system. The statistics are supported by a cursory examination of the categories. For example, for a leukaemic admitted to hospital for a day’s chemotherapy the hospital would be reimbursed the same amount as for a 3 week long admission for a bone marrow transplant. The intention of using such methods of reimbursement is to incentivise providers to allocate resources according to need, based on an appropriate sharing of risks and responsibilities. It also requires that genuine, unavoidable costs be adequately funded. In the case of the leukaemic, reimbursing on the basis of MBC would simply result in hospitals not offering bone marrow transplants. 3.2.4 Conclusions While MBCs might superficially look somewhat like a DRG-type categorisation system, both their face-validity and statistical performance suggest that they should not be used for this purpose. The RVUs provided might be used for internal benchmarking purposes and cost projections, but should probably not be used as the basis for payment of providers. Migration to diagnosis-based global fees for reimbursement purposes remains a desirable objective however. Two approaches are suggested to achieve a suitable tool for this purpose: 1. Adaptation of MBCs to reflect resource homogeneity. By adding an extra digit, or even a binary split to each MBC, their resource homogeneity could likely be substantially improved. The positioning of these splits would require extensive statistical analysis using well validated data, however, and is not an exercise that should be taken lightly. The end result would be a home-grown ‘DRG type’ categorisation system. An added problem with this approach is that the Minimum Benefit categories are likely to be undergoing repeated change over the coming years. This will imply a change in reimbursement values irrespective of whether this is in line with resource homogeneity. The final step in this process would be to hard-code the categorisation system into an automated grouper, which would automatically assign both MBCs and resource categories/RVUs. 2. Adaptation of an imported categorisation system to suit local needs. A diagnostic categorisation system, such as the HCFA DRGs, could be adapted to read local diagnosis and procedure codes. In this instance, the basic structure of the categories would already be designed for resource homogeneity, and they would only require adaptation where South African clinical practice differed significantly from practice in the country of origin. This would appear to be a more focused and realistic approach, rather than trying to patch up a categorisation system that was designed for an entirely different purpose. It would also be congruent with approaches used in most other countries. 4. References Soderlund, N., Gray, A., Milne, R. and Raftery, J. (1996) Case mix measurement in English hospitals - an evaluation of five methods for predicting resource use. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 1, 10-19. Soderlund, N. and Peprah, E. (1998) An essential hospital package for South Africa selection criteria, costs and affordability - Monograph no 52, Johannesburg: Centre for Health Policy.