volcanic risk and hazard in mainland australia

advertisement

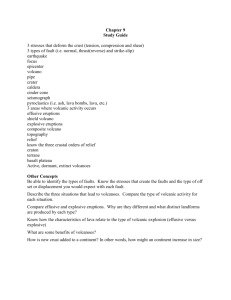

The risk of volcanic eruption in mainland Australia E B Joyce School of Earth Science, University of Melbourne Melbourne VIC 3010 ebj@unimelb.edu.au SUMMARY The young volcanoes of the Australian mainland are made up of the Newer Volcanic Province of Victoria and southeast South Australia (NVP), and a number of separate provinces in far north Queensland. These volcanic fields are similar in age, and in their numerous scattered scoria and lava cones, extensive basalt flows, and maar/tuff ring eruptions of phreatic origin. Australian volcanologists and seismologists now agree that youthful ages imply the possibility of further activity. A risk and hazard map for the NVP (Joyce 2005) demonstrates that volcanic activity must be considered a serious environmental hazard and risk for the Australian mainland. Key words: volcanic, risk, hazard, Australia INTRODUCTION In southeastern Australia, nearly 400 small, monogenetic scoria cones, maars and lava shields have been built up by Strombolian/Hawaiian areal eruptions over the past 6-7 Ma in the Newer Volcanic Province (NVP) of southeastern Australia (Nicholls & Joyce 1989). Fluid basalt flows have spread laterally around vents, often extending for many tens of kilometres down river valleys. Where the lava flows have blocked drainage, lakes and swamps have formed. Phreatic eruptions have deposited ash and left deep craters, often now with lakes. The youngest activity has been dated at 4000-4300 B.P. In northeastern Australia, from Townsville and north to Cooktown, eight distinct regions have been studied, and found to show many of the features of southeastern Australia (Fig. 1). VOLCANIC RISK AND HAZARD IN MAINLAND AUSTRALIA Most comments on volcanic risk and hazard on mainland Australia refer to the southeastern Australia area and the Newer Volcanic Province. However the conclusions reached here apply equally to the extensive volcanic provinces of similar type and age in northeastern Queensland, although this area will not be discussed in detail. Most suggestions regarding volcanic risk have been based on the young appearance of volcanoes and their lava flows and ash deposits. The explorer Major Mitchell recorded the volcanoes of Southeastern Australia in 1836, just 170 years AESC2006, Melbourne, Australia. ago, and with the publication of his report in 1838 the youthful appearance of the volcanic region’s features became widely known. Accounts by Bonwick (1858) and BroughSmyth (1858) added to Mitchell’s observations, and the area became well-known for its youthful volcanic features. With the advent of radiocarbon dating the young age of many of the area’s features was confirmed. Australian volcanologists and seismologists now agree that the youthful age and probable frequency of eruptions imply the possibility of further activity in both southeastern and northeastern Australia, e.g. Blong (1989) states that the "volcanism is so youthful that the possibility of future intraplate eruption in the region cannot be ruled out". A second approach has been to develop an overall view of the activity of the NVP (Hilmansyah 1985). Using K/Ar dates which show the province began its activity some 5 Ma ago, and a catalogue of eruption points which list approximately 400 volcanoes, simple arithmetic can be used to show the an average separation between eruptions of 12 500 years. With Mt Gambier the youngest dated volcano at some 4 000 to 4 300 BP, it can be argued that a further eruption is overdue. A DETAILED CHRONOSEQUENCE APPROACH A third approach is to attempt to describe in detail the frequency of volcanic eruption over time. With fifty K/Ar dates and a similar number of radiocarbon dates, there are many gaps in the record, not the least being the problem of relating dated flow samples to their points of eruption. Recently attempts have been made to fill the gaps in the dating record by using geomorphology and soils to group flows and eruption points of similar age, and then use available dates to assign ages to otherwise undated activity. This method is discussed in more detail in Joyce (2005). Mapping of flows as Regolith Terrain Units or Regolith Landform Units (Joyce 1999) have been assisted by the use of radiometric imagery obtained by the Geological Survey of Victoria. A map of flows by ages can then be used to give a list of volcanoes by ages. Further work is needed, and in particular further dating of the younger flows, ash deposits and volcanoes, but a pattern of eruption over time is emerging, in particular a greater frequency of activity during the last 30 000 to 50 000 years. This suggests a frequency in recent times of some 2 000 years between eruptions (Joyce 2005). A formal statistical study is now underway. This strikingly small period might be argued as too small, if volcanoes were not evenly spread though time, but erupted in groups or clusters, allowing for longer gaps between activity, as suggested recently for the Auckland area of New Zealand, a province with similarities to the NVP and north Queensland provinces. 1 Volcanic risk E B Joyce STUDYING SMALL MONOGENETIC VOLCANOES community, and for planners within local government and emergency organisations. Many provinces or fields with small monogenetic volcanoes are found across the globe, and many are of post-Miocene age, and were catalogued in a study by the IAVCEI, and the southeastern and northeastern Australia data was compiled but unfortunately not published. However the catalogue from southeastern Australia has provided much detail for further analysis. Where are the volcanologists with experience in such areal, monogenetic eruptions? Australian volcanologists have worked on major volcanoes in active areas such as Papua New Guinea and the Pacific islands. Much expertise with large active volcanoes also exists in New Zealand. Perhaps the best assistance would come from volcanologists who are familiar with the past four decades of activity on the big island of Hawaii, where a scoria cone and a lava shield have been constructed, and numerous flows have destroyed infrastructure and led to the evacuation of local residents, as well as the need to look after the many tourists who have been attracted to such relatively benign eruptions. Such volcanoes are found in France and Germany, in the southwest United States, in East Africa, Central and South America, and across the Pacific including in New Zealand. Most are young, and often strikingly so, but few have been active in historical times. Maar eruptions have been observed in Alaska, and the eruption of Paricutin in 1943 in Mexico, in a closely-settled farming area, was well-recorded by the United States Geological Survey, from the early and rapid cone construction, then the formation of a lava field and ash deposits which damaged or destroyed villages and farm land, to the current fumarolic stages sixty years later. Other models for future eruption can be based on observation of the small scale activity of cone building and lava flows observable on such large volcanoes as Mt Etna, but the best studied analogue is the continuing and now 40 years old eruptions in the east rift zone of Kilauea, on the big island of Hawaii, recorded in great detail by the USGS, and studied by many local and visiting volcanologists. CONCLUSIONS A scenario for southeastern or northeastern Australia can be presented in which several volcanoes, perhaps of different types (maar, eruption scoria cone building, extensive lava flows production) might occur at intervals of say 5,000 or 10,000 years. Such scenarios focus our attention on what sort of complex volcanic activity emergency response organisations and the community should be preparing for. Little warning of an eruption would be expected. Minor seismic activity with small earthquakes might precede the eruption by some weeks, and there could also be minor uplift or subsidence of the ground surface, and perhaps changes in ground temperature, and the exhalation of volcanic gases and steam. Maar activity upwind of a town or one of the major cities of the region, such as Melbourne or Ballarat, would provide particular problems from ashfall and base surge flows. In contrast, lava flows would follow the general slope and mostly move southwards down pre-existing valleys (Fig. 2). Hazard impacts of lava and ash would include property and infrastructure damage; effects on people, farm animals and crops; water pollution and stream derangement; and grass and forest fires. There could be associated earthquakes and ground deformation. Emergency management would be concerned with evacuation planning, diversion or control of flows, removal of ash and scoria from roofs and roads, control of fires and floods, and the repair and rebuilding of infrastructure, especially roads and bridges. Government bodies should be planning for preparedness and mitigation, and eruption scenarios should be developed and publicised. Public education will be necessary, both within the local AESC2006, Melbourne, Australia. Figure 1. Young volcanic areas of Australia. A: Maer, Torres Strait; B & C: Sturgeon, Nulla, Chudleigh, McBride, Wallaroo, Atherton, Piebald & McLean; D: Bundaberg & Gayndah; E: Eastern Uplands; F: Western Victoria; G: southeastern South Australia. 2 Volcanic risk E B Joyce REFERENCES Blong, R.J. 1989. Volcanic Hazards, in Johnson, R.W. (ed.): Intraplate volcanism in eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press: 85-88. Bonwick, J. 1858. Western Victoria, its geography, geology and social condition. Thomas Brown, Geelong (reprinted Heinemann Australia, 1970). Brough-Smyth, R. 1858. On the Extinct Volcanos of Victoria, Australia. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 14, pp. 227-235. Hilmansyah, L. 1985: A volcanic hazard assessment of the Newer Volcanics in Victoria and New South Wales. unpublished M.Sc.thesis, University of NSW. Johnson, R.W. (ed) 1989. Intraplate Volcanism in Eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Joyce, E. B. 1999. A new regolith landform map of the Western Victorian volcanic plains, Victoria, Australia, In Taylor, G & Pain, C. (eds) Regolith ‘98, Australian Regolith & Mineral Exploration, New Approaches to an Old Continent, Proceedings, 3rd Australian Regolith Conference, Kalgoorlie, 2-9 May 1998, CRC LEME, Perth, pp.117-126. Joyce, Bernard, 2005. How can eruption risk be assessed in young monogenetic areal basalt fields? An example from southeastern Australia. Special issue on volcanic geomorphology, Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie NF, Suppl.Vol. 140, 195-207. Mitchell, T.L., 1838. Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia. T. & W. Boone, London, 2 vols. Nicholls, I.A. and Joyce, E.B., 1989. Newer Volcanics, Victoria and South Australia, East Australian Volcanic Geology, in R.W. Johnson (ed), Intraplate Volcanism in Eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 137-143. Figure 2. Mapping of eruption types and ages with an indication of volcanic risk and hazard for the Newer Volcanic Province of southeastern Australia (Joyce 2005). AESC2006, Melbourne, Australia. 3