Analgesia and sedation in the critically ill

advertisement

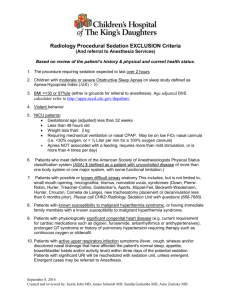

http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/eselect/cc4.htm Analgesia and sedation in the critically-ill Graeme A McLeod 1 Introduction Pain, anxiety and distress are common sequelae in the critically ill and injured patient. Postoperative pain, prolonged immobilisation, thirst and repeated stimuli such as tracheal suction are perceived by patients as amongst their most distressing experiences. In addition, lack of sleep, the effects of the underlying disease process and sedative medication may contribute to confusion, disorientation and, in some instances, the development of a psychotic state. Sedation and analgesia can therefore be regarded as ‘caring for the physical and psychological comfort of critically ill patients receiving end organ support’. A variety of management options is available with which the surgeon needs to become familiar. In considering pharmacological regimens, it should always be remembered that all have unwanted side effects. The balance of advantages and disadvantages should always be in the patient’s favour. Finally, in recent years cost-benefit issues have become increasingly important. 2 Aims After working through this module and applying it to your clinical practice you should be able to: describe the inter-related psychological and physiological changes contributing to pain, anxiety and distress in the critically ill assess pain and the need for analgesia and sedation in the critically ill give an account of the treatment modalities available and their effects on ill patients manage patients requiring routine pain relief and sedation recognise when to refer for specialist pain advice. 3 Examples in practice We have presented you with seven case studies which you may commonly come across in clinical practice. We suggest you read each of the individual examples and accompanying key issues. Try relating each to the other. Case 1 - Fractured ribs A previously fit 22-year-old male is admitted to the Accident and Emergency department following a 30 foot fall while climbing. He has fractures of ribs 6-11 on his left side and a fractured pelvis. He is in severe pain and has difficulty coughing. Arterial oxygen saturation is 86%. Key Issues Pre-hospital pain relief. Mode of injury as a guide to severity of injury. Indications for referral to High Dependency Unit (HDU)/Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Consideration of analgesia in relation to other treatment modalities. Indications for referral to pain team for analgesia. Role of pain relief in affecting duration and outcome from illness. Planning analgesia/sedation strategy. Choice of analgesia/sedation agents/ regimens. Cost-benefit issues. Case 2 - Epidural analgesia in the postoperative period An 82-year-old lady with a history of chronic obstructive airways disease is in the High Dependency Unit (HDU) following a gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Pain relief is excellent but during the night sedation scores rise in successive hours. Her respiratory rate falls to 6 breaths/min. Respiratory depression in the critically ill. Risk factors for postoperative respiratory depression. Advantages/disadvantages of epidural analgesia. Monitoring in HDU/ICU. Scoring systems for assessing analgesia and sedation. Case 3 - Extradural haematoma A 59-year-old man had an elective and uneventful grafting of an aortic aneurysm. He remained pain free on coughing and movement with epidural analgesia for 50 hours in the HDU. Another emergency admission to HDU necessitated his transfer to the ward and the epidural catheter was removed. He had received heparin thromboprophylaxis one hour previously. On transfer he mentioned that his legs felt heavy. Complications of epidural catheterisation. Indications for neurosurgical opinion and radiology. Timing of surgical intervention. Indications for sedation. Assessment of analgesic and sedative requirements. Approach to analgesia and sedation influenced by oxygenation and ventilatory strategy. Communication with patients, relatives and staff. Ethics of analgesia/sedation in the terminally ill. Outcome in sepsis Complications of long term administration of parenteral sedation. Indications for re-laparotomy. Reversible causes of confusion. The environment of ICU. Organic brain disorders. Case 6 - Weaning from ventilator A 63-year-old female with chronic respiratory disease and pancreatic abscess has been ventilated for two weeks. She has made a good recovery from surgery but is not waking up despite stopping sedation. Weaning protocols. Pharmokinetics and pharmodynamics in critically ill patients. Sedation policies. Side effects of prolonged sedation. Case 7 - Road traffic accident Case 4 - Life threatening sepsis A 68-year-old non insulin dependent diabetic with hypertension and ischaemic heart disease is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) following laparotomy for perforation of sigmoid diverticular disease and faecal peritonitis. She has severe sepsis and requires increasing oxygen concentration to maintain P02. Case 5 -ICU psychosis A 72-year-old alcoholic with postoperative pneumonia becomes confused, anxious, restless and hallucinates two days after discharge from ICU. A 30-year-old man is admitted to the A&E department following a car accident. He has fracture of ribs 9-11 on his left side, lung contusions and pneumothorax requiring a chest drain. After resuscitation he required a splenectomy and repair of liver tear and now requires transfer to the regional Intensive Care Unit for postoperative care. Role of nurse and physiotherapist. Pre-hospital analgesia. Non-pharmacological methods of analgesia. Preparation for transfer. Communication with transfer team and ICU. Guidelines for transfer of the critically ill. Indications for ventilation 4 What you should think about 4.1 Pathophysiology Pain, anxiety and distress in the surgical patient can be described under two broad headings: psychological physiological o pain pathways o stress response to pain o vital organ function o outcome from surgery. Both the psychological and physiological aspects of pain, anxiety and distress are closely inter-related. However, assessment of analgesic requirements requires knowledge of an individual patient’s psyche, including past experiences of pain and distress, and thus the psychological aspects of analgesia and sedation in the critically ill will be discussed first. 4.1.1 Psychological The environment of the hospital has a profound effect on patients’ wellbeing. Critically ill patients suffer major sleep disturbance and survivors of critical illness state that sleep disturbance is one of the most unpleasant features of their stay in hospital. The psychological effects of lack of sleep are confusion, disorientation, depression and hallucinations. Sleep disturbance Sleep has a metabolic role. It is required for tissue growth by stimulating the release of anabolic hormones for protein synthesis. Sleep deprivation promotes the secretion of catabolic hormones such as cortisol, glucagon and catecholamines and increases loss of body nitrogen. Sleep deprivation causes: Critically ill patients are looked after in an artificial and isolated environment and may suffer anxiety, pain and distress. They feel immobilised by tubes, cables and catheters and are disturbed by machinery alarms and bleeps. Overheard staff conversations can create confusion and observing the fate of other patients, such as cardiac arrest or death, may cause great distress. Difficulty in communication is often a major concern. Patients are subject to artificial light and may be sedated, ventilated or fed continuously. They may be reliant on infusions of inotropes and may require dialysis for acute renal failure. Critically ill patients lose track of time. In those treated in the ICU, 25% of survivors cannot even remember any events, yet 25% retrospectively describe symptoms of ICU psychosis. Wallace et al in 1988 found that 3% of survivors described being terrified and 8% found ICU an unpleasant experience, although 45% thought being a patient in ICU was tolerable. ICU psychosis In a small number of patients the cumulative effects of sleep disorder, the disease process and the use of sedative and analgesic drugs may present typically on days 3 to 7 as ICU psychosis (see Case 5). This is characterised by disordered thinking and speech, hallucinations and a fear of death. The symptoms are characteristically worse at night and only slowly disappear following discharge. 4.1.2 Physiological Pain pathways Pain is transmitted from peripheral subcutaneous mechanoreceptors and nociceptors and by Ad and C afferent neurones. The Ad fibres are myelinated and responsible for rapid transmission of sharp, localised pain. The unmyelinated C fibres are slower and transmit dull, aching, poorly localised pain. These fibres enter the dorsal horn of the spinal cord where they synapse in laminae II and III (substantia gelatinosa). The dorsal horn is a complex area, regulated by a multitude of neurotransmitters, the most prominent of which is Substance P. An intermediary neurone crosses the midline to the lateral spinothalamic tracts which ascend to the lateral side of the thalamus before being projected to the cerebral cortex. The spinal cord has its own inbuilt mechanism for combating pain. It is called the descending inhibitory fibre which descends to the dorsal horn and releases the transmitters noradrenaline and acetylcholine. These attenuate the passage of painful impulses through the dorsal horn. Pain fibres also ascend in the spinoreticular tracts to the pons and medulla and are responsible for the state of arousal and sympathetic drive due to pain. This reflex activity via efferent sympathetic fibres results in profound effects on vital organs such as the heart, lungs and gut. The diagram below illustrates the changes in dorsal horn function during surgery. Painful stimuli during surgery activate dorsal horn neurones which subsequently activate the sympathetic nervous system. The increased activity of dorsal horn neurones is depicted by the shaded area in the diagram. Cutting a peripheral nerve during surgery leads to a pronounced and protracted increase in spinal cord activity, resulting in further activation of neuronal activity, muscle spasm and even greater increase in painful stimuli. S - painful stimulus H - area of hyperalgesia IML- intermediolateral cells SG - symphatic ganglion This sustained stimulation from surgery increases the size of the receptive field and alters neurotransmitter function in the dorsal horn which is associated with the development of chronic pain syndromes. An increase in activity in the dorsal horn is called ‘wind-up’, such that spinal neurones have an exaggerated response to a normally painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) and even react to non-noxious stimuli (allodynia). N-methyl Daspartate (NMDA) receptors in the spinal cord seem to be involved in this process. The stress response in critically ill patients Patients develop a stress response during and after surgery which is characterised by pain, a neuroendocrine response, hypercatabolism, hypercoagulation and immunomodulation. This can last several days. Postoperative pain results in lethargy, immobility and muscle spasm. In addition, ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) grade III and IV patients may suffer myocardial infarction, thromboembolism and impaired respiration and gastrointestinal ileus. How can we assess patients’ pre-operative condition? American Society of Anesthesiologists Score (ASA) I normal healthy individual II mild systemic disease III severe incapacitating disease IV incapacitating disease affecting life V moribund patient not expected to survive with or without operation Anaesthesia & Analgesia 1970, 49:564 Initiation of the stress response is primarily due to afferent nerve impulses combined with release of humoral substances (such as prostaglandins, kinins, leukotrienes, interleukin-1, and tumor necrosis factor), while amplification factors include semistarvation, infection, and haemorrhage. In particular, the proinflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-6 play a significant role in the response to major surgery. The neuroendocrine and cytokine response to major surgery in critically ill patients. The endocrine response in critically ill patients is profound and catecholamine secretion can promote arrhythmogenesis, tachycardia and hypertension. Cortisol is released from the anterior pituitary in response to stimulation by adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). Plasma levels of both these hormones are elevated in response to surgery. The magnitude of the cortisol response correlates with poor outcome. Plasma cortisol levels >1800 nmol/l have been associated with an increased risk of death in ICU. Conversely, an inadequate cortisol response to surgical stress, as determined by a Synacthen (ACTH) test, is associated with a poor outcome. The chart below illustrates the relationship between cortisol and ACTH in a 62-year-old female in the first two days of intensive care following a road traffic accident. A general guide to outcome from intensive care for the overall ICU population is the Acute Physiological and Chronic Health Evaluation Score (APACHE), although this gives no guide to the need for sedation. This patient’s score is 20, indicating that she is severely ill. The diagram indicates a close correlation between cortisol and ACTH. The diagram below demonstrates a marked rise in plasma cortisol level in a 75-year-old male to almost 1500 nmol/l on the second day of admission to the ICU. In contrast, cortisol levels in unstressed individuals range from 150-600 nmol/l. His APACHE score was 29. He subsequently died in ICU from multi-organ failure. Effect of pain and analgesia on vital organ function Cardiac disease Pain has a detrimental effect on myocardial function. The resultant tachycardia and hypertension both increase myocardial oxygen consumption in the critically ill and tilt the oxygen supply/demand balance in the direction of myocardial ischaemia. In turn, this stimulates a sympathetic response leading to further ischaemia and myocardial dysfunction. Epidural anaesthesia has been shown to improve ventricular emptying and wall function in surgical patients including those undergoing cardiac bypass surgery. Neural blockade of cardiac sympathetic fibres is associated with dilatation of post-stenotic coronary arteries and a reduction in the incidence of postoperative silent myocardial ischaemia which is the predominant risk factor for postoperative myocardial events in non cardiac surgery. Patients undergoing surgery for arterial disease are at increased risk of both venous and arterial thrombosis following surgery due to an increase in coagulation factors and inhibition of fibrinolysis. Respiratory disease Pain leads to diaphragmatic dysfunction which is associated with reduction in functional lung volumes of up to 50% and a diminished ability to cough (see the diagram opposite). Inability to clear secretions can often lead to postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia, especially in those with chronic lung disease and limited respiratory physiological reserve. Opioids and anaesthetic agents both depress central respiratory drive and are associated with episodes of profound postoperative hypoxaemia and apnoea for at least 72 hours postoperatively. Extradural analgesia has been shown to improve postoperative respiratory function, facilitate physiotherapy and has led to fewer pulmonary complications compared to systemic analgesia. Effects of incision - chest and diaphragm Gastrointestinal function Gastrointestinal function is impaired after abdominal surgery. The gut is innervated by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The latter promotes gut activity, whereas the former inhibits gut propulsion. Opioids by any route delay gastric emptying and prolong orocaecal transit time. Continuous epidural anaesthesia and sympathetic block with local anaesthetics may potentially reduce the duration of ileus and improve colonic blood flow and anastomotic healing. This may allow earlier feeding and prevention of small bowel mucosal damage. Effects of incision - sympathetic chain and gut Effect of pain relief on outcome from surgery The modifying effect of pain relief on the surgical stress response is dependent upon the technique of analgesia. Systemic opiate administration, as well as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, exerts only a minimal dampening of the response. Afferent neural blockade with local anaesthetics is the most effective technique for reducing the endocrine-metabolic response, but is more striking in operations on the lower part of the abdomen. Thoracic epidural analgesia for upper abdominal or thoracic surgical procedures only partially attenuates the stress response, probably because of an inability to block the phrenic and vagal nerves. The benefits of analgesia on outcome from surgery were recognised many years ago. “Interrupting the neural input from an injured area will neutralise the ancient defence mechanisms to violent injury and restore appropriate movement and metabolic activities that will permit sufferers to recover more safely, speedily and effectively from the therapeutic cocoon in which they find themselves.” GW Crile, 1915 Low-dose combined analgesic regimens may provide total pain relief and attenuate the stress response. Unfortunately, the benefits of epidural analgesia with synergistic mixtures of local anaesthetic and opioid are often not taken advantage of. Analgesia should allow coughing, mobilisation and early feeding and this has the potential to improve postoperative outcome. Two studies have demonstrated that postoperative pain control in the critically ill is not only a humanitarian act but also a therapeutic intervention which itself can have a marked effect on outcome (their results are displayed in the table below). In both studies, epidural analgesia for at least 36 hours was associated with a significant reduction in cardiac and respiratory morbidity, intensive care stay and hospital costs. Urinary cortisol excretion, a marker of the stress response, was significantly diminished in those receiving epidural analgesia in Yeager’s study. “Acute pain relief should be part of an ‘acute rehabilitation service’ improving physical and mental function after major surgery. The aim ultimately is for a ‘return to normal function’.” Kehlet, British Journal of Anaesthesia 1997 Yeager et al 1987 CCF MI Death Infection Tuman et al 1991 CCF MI Death Infection Total complications General anaesthetic/epidural General anaesthetic/systemic opioid 1 0 0 2 10 3 4 10 2 0 0 2 13 4 3 0 8 52 4.2 Differential diagnosis This section outlines important considerations when reaching a diagnosis and planning treatment. 4.2.1 Causes of delirium Airway o hypoxaemia, hypercarbia Breathing o carbon monoxide poisoning Circulation o anaemia, cardiac failure Drugs o steroids, lead, manganese Endocrine o hypoglycaemia, adrenal insufficiency Infection o encephalitis, meningitis Metabolic o acidaemia, alkalaemia, electrolytes, hepatic failure, renal failure, hypothyroidism, vitamin deficiency Neurological o haemorrhage, abscess, seizures, tumour Withdrawal o alcohol, opioids 4.2.2 Undersedation Sudden changes in conscious level allow patients to wake up suddenly, increasing agitation and distress. Coughing and intolerance of ventilation dislodges tubes and lines, with haemodynamic upset. 4.3.3 Oversedation Patients are less likely to become disconnected from the ventilator if over-sedated but this is at the expense of pressure sores, deep venous thrombosis, muscle wasting and nerve injury. Persistent deep sedation due to drug accumulation may prolong ventilation, increase psychological disturbance, immunological depression and the risk of infection. Gastric stasis and ileus delay enteral feeding. Thus inappropriate heavy sedation prolongs ICU stay. 5 What you should do In the acute situation, initial focus should be on management of the airway, breathing and circulation. Relief of pain, anxiety and distress is dependent on simple measures such as reassurance, immobilisation of limb fractures, inhaled entonox or, if feasible and appropriate, local anaesthetic blocks, e.g. femoral nerve block for fractured neck of femur. Any subsequent analgesia should be given intravenously by slow, titrated boluses of opioid such as morphine. Supplementation of analgesia should be given only after assessment of the patient’s response to the initial bolus. Subsequent boluses of morphine should be given 2-3 minutes apart to allow assessment of analgesia, level of sedation and vital signs. Intramuscular opioids may not be adequately absorbed from the site of injection due to peripheral vasoconstriction in the ill patient. Improvement in the patient’s condition, and subsequent vasodilatation, may result in rapid absorption of opioid into the circulation, with the risk of respiratory depression. 5.2 Subsequent management Although the focus of this section will be on pharmacological agents, a number of non-pharmacological approaches are initially important in reducing the impact of illness and injury in the critically ill patient. Maintaining patient communication is a prime consideration. Patients may still be able to hear, even when sedated to apparently deep levels, and require explanation and reassurance. Relatives make a substantial contribution to care. Set times during the day should be allocated for ward rounds, examination, physiotherapy and rest. Patients should have light sedation in daylight hours to promote communication, allowing assessment of their psychological and physiological wellbeing. 5.2.1 Managing pain and sedation Analgesia and sedation are inter-related. Pain control is an integral part of any sedation regimen and a successful sedation regimen should reduce the emotional components of pain. Other advantages include better patient care, comfort and safety. “A background narcotic... infusion must be the first step in all sedation protocols.” Peruzzi, Editorial Critical Care Medicine 1997 However, pain is subjective and is difficult to assess if patients are sedated and ventilated. Critically ill patients are often confused and disorientated as a result of the environment of the ICU, sedative drugs and the severity of their disease. They therefore may have a poor ability to interpret and express feelings of pain. It is therefore difficult to judge pain in critically ill patients. The usual visual signs such as facial grimacing, and vital signs such as sweating, tachycardia and hypertension, may be misleading. Practice has now changed. No longer are patients kept in ICU at deep levels of sedation and paralysed. A lighter level of sedation is preferred; either awake and comfortable or asleep and easily rousable. There is also greater awareness that sedation requirements vary with stage of illness. Patients may occasionally require deep sedation, analgesia and even paralysis after admission for postoperative analgesia, placement of lines and procedures such as percutaneous tracheostomy, but sedation can be tailored to the patient’s requirements as their condition improves. Assessment of requirements The dose of sedatives and analgesics should be titrated against patient response. This will improve analgesia and anxiolysis, minimise overdosage and reduce untoward side effects. The requirement for analgesia and sedation should be monitored daily as the illness evolves. Monitoring of sedation requirement in a ventilated critically ill patient is essential. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted sedation regimen in ICU. Sedation is difficult to quantify and no routine, clinical monitor of sedation is available. Despite lack of agreement on the ‘best’ sedation score it is more important that one is used to monitor sedation trends in individual patients. “Optimal sedation results in a patient who is free of pain and anxiety, tolerates medical procedures and can be aroused from light sleep, thus enabling effective neurological assessment.” Ledingham & Bion 1987 For further details of the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the SELECT module ‘Altered consciousness/confusion’. Severity of illness in intensive care is measured by the APACHE score, and assessment of neurological function by eliciting verbal and motor responses to voice and pain (Glasgow Coma Scale). Neither makes an assessment of comfort and cannot be used as a sedation score. Examples of commonly used sedation scores in intensive care are given below: Ramsay score 1974 Awake levels 1 anxious, agitated or both 2 co-operative, orientated, tranquil 3 Asleep levels 4 responds to commands only 5 6 brisk response to loud auditory stimulus sluggish response to loud auditory stimulus no response to loud auditory stimulus The Ramsay score is widely used by many intensive care units. Addenbrooke score 1991 0 agitated 1 awake 2 roused by voice 3 roused by tracheal suction 4 unrousable 5 paralyses 6 asleep The Addenbrookes score includes awareness of sleep and use of neuromuscular blocking agents. Levels 1 and 2 represent the ideal level of sedation. Voice and tracheal suction have been utilised as stimuli because they are reproducible and do not inflict any painful stimulus. Pain assessment Formal testing of pain relief using patient verbal rating scores (VRS) or visual analogue scores (VAS) is only possible if patients are awake and therefore applies to the HDU environment or in the weaning stages of ICU. Several national UK reports have stressed the importance of routine systematic assessment of pain in all patients. The following verbal rating score for assessment of pain is widely used in many countries and emphasises the importance of dynamic pain relief - the analgesia of coughing and movement. Pain score 0 no pain at rest or on movement 1 no pain at rest, slight on movement intermittent pain at rest, moderate on 2 movement continuous pain at rest, severe on 3 movement Assessment of sedation level is important in critically ill patients. The use of analgesics and sedatives, and the disease state can all result in excessive sedation. Regular assiduous assessment of sedation can identify those patients at risk of respiratory depression. 5.3 Investigations Investigations should include a history of concomitant medication and any other illnesses, such as cardiac failure, elevated intracranial pressure, hepatic disease and renal failure, which may render patients more prone to the side-effects of pharmacological agents. 5.4 Treatment Critically ill patients vary in their response to analgesic and sedative drugs. Pharmokinetic changes, such as increased volume of distribution, reduced clearance, acid-base changes and multiorgan dysfunction, all alter drug requirements. Nevertheless, pharmacological agents can assist the patient in coping with his illness, particularly during periods of increased stress, discomfort and pain such as tracheal suction, physiotherapy and transport. 5.4.1 Pharmacological agents The ideal drug for sedation should have a simple, rapid onset of action, short duration and be easily titrated to a desired sedation level. Degradation should be independent of hepatic or renal function, with no local or systemic side effects. The ideal drug should not accumulate or have any active metabolites. Use of single drugs for sedation is often associated with excessive side effects. Combinations of drugs can be used to obtain optimal therapeutic effect while minimising adverse effects, e.g. morphine and midazolam. Analgesic and sedative drugs The following section will discuss drugs used for analgesia and sedation including: benzodiazepines propofol inhalational agents non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs opioids adjuvant drugs. Benzodiazepines Passage of sensory information, such as pain, through the CNS is filtered by the gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system. Occupation of relevant receptors by benzodiazepines enhances the effect of GABA. This sieve-like effect on neural transmission further reduces the number of stimuli reaching the higher centres and produces sedation, anxiolysis, amnesia, muscle relaxation and anticonvulsant effects. Diazepam has been used for the sedation of critically ill patients. However, its half life of 36 hours and active metabolites results in prolonged sedation. It is now rarely used in surgical practice and has been replaced by newer drugs such as midazolam. Midazolam is an unusual drug. It exhibits a pH dependent phenomenon in which its constituent imidazole ring remains open at pH values below 4. Once in the blood stream, the change in pH alters its ring structure, allowing the molecule to change from being water to fat-soluble. This lets it cross lipid membranes and exert its effect in the CNS. Similar to most benzodiazepines, midazolam is bound extensively to plasma proteins. Low plasma albumin levels in the critically ill increase its volume of distribution and prolong its half life of 1.9 ± 0.9 hr. Midazolam is metabolised in the liver and excreted in the urine. Its principle metabolite is 1hydroxymidazolam, which retains 10% of activity. Delayed metabolism and prolonged recovery has been reported in the critically ill, particularly with hypovolaemia and in the elderly. Think about Case 6. How would you manage sedation for a long stay patient in ICU? Consult your Intensive Care colleagues for the benefit of their experience in the management of such patients. Pharmokinetics of sedative agents Vdss (1kg) Clearance mlkg/min) Propofol 2.8 59.4 Term (hr) 0.9 Midazolam 1.1 7.5 2.7 Etomidate 2.5 17.9 2.9 Ketamine 3.1 19.1 3.1 3.4 12.0 Thiopentone 2.3 Vdss - volume of distribution: T1/2 - half life T1/2 Propofol Propofol (2,6, di-isopropylphenol) is formulated as a 10mg/ml or 20mg/ml oil in water emulsion. It is used for sedation of critically ill adult patients in ICUs because it is easily titratable, has a rapid redistribution, high clearance and is associated with rapid recovery, even after prolonged infusion. Its rapid action makes it an alternative agent for use in specific circumstances, such as insertion of intravascular lines and chest drains, percutaneous tracheostomy, bronchoscopy etc. Patterns of sedation Patients sedated in ICU following surgery exhibit different responses to analgesic and sedative drugs because of their underlying disease state. The following two examples highlight the variation in sedation requirement and response to changes in sedation and analgesia in critically ill surgical patients. Example 1 This was a patient with Guillain-Barré syndrome who was ventilated for respiratory failure. He had no other medical problems and this allowed a more natural sleep pattern at night. Note that the patient required a higher initial dosage of sedative drug to achieve adequate sedation. Thereafter, a constant infusion of sedative drug was given. The graph indicates an increase in sedation score between 32 and 38 hours. This can be attributed to sleep. Example 2 This is an example of a patient with persistently deep sedation. The Ramsay scores were 4 to 6 at all times within the first two days following admission to ICU. Note from the graph that attempts to reduce the dose of sedative drug were not followed by any fall in sedation score. This patient had an APACHE II score of 24 and was severely ill due to the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), secondary to peritonitis. The disease in this instance altered conscious level and it was not possible to manipulate sedation scores. Inhalational agents Volatile agents such as isoflurane or desflurane resemble the ideal sedative. They have a low blood solubility, and sedation is easy to control. Their metabolism (<1%), and therefore elimination, is independent of renal or hepatic function. However, they are expensive and scavenging of gas can be difficult in the ICU. NSAIDs These are particularly good for bony or pleural pain. They may be used in combination with opioids to optimise analgesia. NSAIDs often minimise opioid use postoperatively and hence limit the potential opioid side effects of nausea and vomiting, excessive sedation and ileus. NSAIDs may be administered intramuscularly but care must be taken not to inject into subcutaneous fat as fat necrosis may ensue. Intravenous preparations of NSAIDs are available which are of benefit in the postsurgical patient. However, their use is limited in the critically ill by a potential for gastric mucosal ulceration, bronchospasm and acute tubular necrosis, especially in the face of hypoxaemia and hypotension. Opioids Opioids form the basis of analgesia and sedation regimens for the critically ill. They are valuable even for the non-surgical patient because they provide analgesia from general aches and pains to insertion of intravenous lines. A lack of appropriate analgesia may result in excessive sedation and, hence, side effects from one drug, or severe agitation from poor pain relief. Once analgesia is achieved, specific sedative drugs can be used as required for anxiolysis, distress and invasive procedures. Opioids commonly used in the critically ill include: morphine fentanyl alfentanil remifentanil Morphine will be discussed later in the text. Fentanyl, alfentanil and remifentanil are synthetic opioids. Fentanyl and alfentanil are potent opioids with a rapid onset and short duration of action as a bolus injection. Neither drug releases histamine and thus they are less likely to produce hypotension compared with morphine. Alfentanil is metabolised in the liver with no active metabolites and is suitable for continuous infusion. Its use is restricted to ventilated patients. It is useful for managing analgesia during the weaning period. Remifentanil is a very potent opioid and can only be given as an infusion. It has an ultra-short half life of only a few minutes and is associated with bradycardia and hypotension. The three opioids highlighted above are potent respiratory depressants and should only be administered in specialised areas such as anaesthesia and intensive care. Adjuvant drugs This group includes the neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs). There have been marked changes in attitude towards sedation since the early 1980s. In 1981, 90% of units used deep sedation and paralysis, compared to 15% in 1991. The change coincided with the introduction of SIMV ventilation, enabling patients’ breathing pattern to synchronise with the ventilator and achieve the goal of being asleep but easily rousable. In some patients, however, it is necessary to use NMBAs when oxygenation is critical, or in those with raised intracranial pressure who may suffer prolonged elevation of CSF pressure with coughing, tracheal suction, physiotherapy etc. It should always be remembered that NMBAs are not analgesic or sedative agents. They should be used sparingly, and only after ensuring adequate sedation. Use of NMBAs without appropriate analgesia or sedation may result in patient awareness, anxiety, fear and long term distress. If NMBAs are used, neuromuscular function must be monitored routinely with a peripheral nerve stimulator. Indications for NMBAs intubation initial control of ventilation following admission to ICU increased O2 consumption specific disease states, e.g. tetanus, head injury. Side effects of NMBAs patients are dependent on full ventilation patients require constant nursing attention neurological assessment is hindered deep venous thrombosis bed sores the cough reflex is suppressed prolonged muscle weakness. If NMBAs are used, they should be given in as small a dose and for as short a time as possible, and the patient carefully monitored. 5.4.2 Route of administration This section will discuss the route of administration of analgesic and sedative drugs. This can be divided into: intramuscular intravenous patient controlled analgesia regional analgesia. Intramuscular This is the traditional method of analgesia but is not particularly efficacious as pain can still be severe on mobilisation. There is variable absorption from the site of injection especially in ill, vasoconstricted patients. This is potentially dangerous as any subsequent vasodilation may result in a large bolus in the circulation. Of particular relevance is the critically ill child or elderly person. Issues still exist regarding the misconception of overdosage and addiction and this often prevents optimal analgesia. Intravenous Morphine provides the best compromise between ease of use and cost in UK practice and, as an infusion, forms the basis of most sedation regimens. It is a m agonist given as a slow incremental bolus of 0.05-0.1 mg/kg or at a rate of 15-50 mcg/kg/hr, and is metabolised in the liver to the potent morphine-6-glucoronide. Morphine clearance depends on renal function as 5-15% is unchanged in the urine. Like all narcotics, it impairs gastrointestinal function and is associated with pruritus, nausea and vomiting. Patient controlled analgesia Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is a means of titrating morphine intravenously by the patient to a desired level of analgesia via a dedicated intravenous line or one way valve. Analgesic requirements vary considerably between patients and this technique improves patient satisfaction and offers patients a degree of self control. A standard regimen is a solution of 1mg/ml morphine with a 1mg bolus. The minimum time between boluses is described as the lockout time and is usually five minutes. “Up to a 30-fold variation in morphine requirements may occur in the first 24 hours after open cholecystectomy.” A professor of anaesthesia PCA provides pain relief at rest but not on coughing or mobilisation. It has no influence on surgical outcome because many patients are prevented from achieving optimal analgesia by the side effects of opioids such as drowsiness or nausea and vomiting. A lower dose of opioid gives inadequate analgesia, and a higher dose increases the risk of respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting. Similarly, a background infusion increases the risk of side effects and is not associated with any improvement in patient satisfaction compared to PCA. Unfortunately, PCA is a method only available to those who are neurologically and physically able to co-operate. These methods of pain relief involve use of infusion pumps. All patients given drugs by machine require hourly assessment of dose administered and remaining volume to identify early electromechanical dysfunction. Above is an example of analgesia in 360 patients using PCA following major surgery and supervised by the acute pain service. Excellent analgesia can be defined as pain relief on movement and coughing. This was obtained in only 19% of patients, and pain at rest and severe pain existed in 25% of patients. Therefore, patients with analgesia from PCA and those with epidural infusions are two cohorts with quite different pain experiences. Regional analgesia Synergistic mixtures of local anaesthetic and opioid represent the ideal solution for analgesia. Patients develop tolerance to infusions of local anaesthetic alone and the larger dose of drug thus required increases the incidence of motor block and hypotension. Infusions or boluses of opioid alone give satisfactory analgesia but at the expense of opioid related side effects, particularly late onset respiratory depression and delayed return of gut function. Experience of five years of use of synergistic mixtures in a teaching hospital is summarised below. Patients are nursed in HDU or ICU and monitored at the same two hourly intervals, e.g. 0200, 0400, 0600 hrs etc., for pain relief at rest and on movement by a verbal rating score (awake and cooperative patients), sedation score, motor block and vomiting, blood pressure and infusion volume. The diagram below is a schematic representation of the management of pain using epidurals. It demonstrates how trained nursing staff, monitoring patients at regular two-hourly intervals, can optimise analgesia, aiming always for pain relief allowing breathing, coughing and movement. It also indicates when a doctor should be appropriately called. Always check first: Is the pump working? Is the epidural catheter kinked or leaking? Is the epidural catheter in place? Analgesia with epidurals Excellent perioperative analgesia is achieved with epidurals. The diagram below demonstrates that, over a five-year period, patients spent 75% of a mean duration of 52 hours with epidural analgesia, free from pain on movement and coughing. Regimens containing diamorphine appear to offer better analgesia. Only 5% of time was spent in severe pain with a diamorphine based regimen, compared to 8-9% with fentanyl based regimens. A contrast can be made between this graph and that previous illustrating the analgesia obtained from PCA.(see above) The existence of a dedicated Acute Pain Team has reduced morbidity over the five-year period. There has been a reduction in anaesthetist top-ups, nausea and vomiting and motor block. The incidence of hypotension is low; only 1.8% of time is spent with a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg. A common misconception is that epidural analgesia is associated with hypotension. The surgical trainee, when encountering a critically ill patient with hypotension, should exclude all causes of low blood pressure, particularly hypovolaemia, and be prepared to seek appropriate advice. Side effects of epidurals Epidural analgesia offers many benefits but this must be balanced against the risk of potential side effects. Repetitive assessment and rigorous attention to detail can help optimise analgesia and recognise the side effects listed below. As with all technical procedures, epidurals are associated with a technical failure rate which can be minimised in experienced hands. Early referral of any problems to the acute pain team can prevent morbidity. Potential problems are summarised in the following table: Technical wrong interspace leakage Opioids nausea and vomiting pruritis migration respiratory depression catheter displacement sedation infection urinary retention Local anaesthetic motor block hypotension haematoma neurological injury The health economic environment dictates that the cost/benefit ratio of any medical intervention be examined. Attaining excellent analgesia may appear expensive. Epidurals require a higher level of nursing dependency, expensive monitoring equipment and more drugs. However, a potentially shorter stay in ICU or HDU, earlier readiness for discharge from hospital and the prospect of possibly reducing the incidence of chronic pain can make epidural analgesia cost effective. 5.5 Monitoring The following must all be monitored at two hourly intervals (e.g. 0200, 0400, 0600 hr etc): respiratory rate sedation score motor block nausea and vomiting infusion volume blood pressure 6 Outcome The following considerations influence patient outcome: Critically ill surgical patients may suffer pain, anxiety, distress and depression. Lack of sleep and difficulty with communication can often compound these factors. Assessment of analgesia and sedation in the critically ill should take account of both psychological and physiological variables. Scoring systems for analgesia and sedation can help the surgeon administer appropriate treatment. This varies from simple reassurance and immobilisation to pharmacological manipulation of pain relief and sedation. The underlying disease state often dictates the response to analgesic and sedative agents. Excellent analgesia requires routine and assiduous assessment of physiological parameters and pain scores, and trained staff who can titrate to optimal analgesia. Control of incident pain – the pain associated with movement and coughing. The provision of dynamic pain relief allows mobilisation, physiotherapy and early feeding and a ‘return to normal function’. Use continuous effective analgesia to promote function throughout the perioperative period to improve surgical outcome. 7 Summary Pain control in the critically ill goes beyond analgesia as a humanitarian act but is a therapeutic intervention which itself can have a marked effect on outcome. 8 References Adam K, Oswald I (1986). Sleep helps healing. British Medical Journal 289: 1400-1. Carpenter R, Liu S (1995). Epidural Anaesthesia and Analgesia: Their role in post-operative outcome. Anesthesiology 182: 1474- 1506. Cousins and Bridenbaugh (Eds) (1998). 3rd edition. Neural Blockade in Clinical Anesthesia and Management of Pain. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven. Kehlet H (1997). Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. British Journal of Anaesthesia 78: 606-17. Kehlet H (1994). Postoperative pain relief - what is the issue. British Journal of Anaethesia 72:375-7. Kehlet H, Dahl JB (1993). The value of multi-modal or balanced analgesia in postoperative pain relief. Anesthesia and Analgesia 77:1048-56. Liu SS, Carpenter RL, Mackey DC et al (1995). Effects of perioperative analgesia technique on rate of recovery after colon surgery. Anesthesiology 83:757-65. Mangano DT, Siliciano D, Hollenberg M, Leung JM, Browner WS, Goehner P, Merrick S, Verrier E (1992). The Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group: Postoperative myocardial ischemia: Therapeutic trials using intensive analgesia following surgery. Anesthesiology 76:342-53. McLeod G, Dick J, Wallis C et al (1997). Critical Care Medicine 25: 1976-81. McLeod G, Wallis C, Cox C et al (1997). Use of 2% propofol to produce diurnal sedation in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Medicine 23: 428-34. Tuman KJ, McCarthy RJ, March RJ, DeLaria GA, Patel RV, Ivankovich AD (1991). Effects of epidural anesthesia and analgesia on coagulation and outcome after major vascular surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia 73:696-704. Yeager M, Glass DD, Neff RK et al (1987). Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in high risk surgical patients. Anesthesiology 66(6): 729-36.