Ethology Ecology & Evolution 4: 139-149, 1992 - digital

advertisement

Antipredator aspects of fallow deer bebaviour

during calving season at Doñana National Park (Spain)

C. SAN JOSÉ and F. BRAZA

Estación Bioldgica de Dotiana, CSIC Apdo 1056, 41080 Sevilla, Spain

Received 26 June

1990, accepted 1 March 1991

This study evaluates some morphological, ecological and behavioural aspects of

fallow deer mothers and fawns during the calving season in order to know the

antipredator tactics selected in this species living in a particularly open hahitat at

Doñana National Park. In this area (allow deer give birth in synchrony during the first

fortnight of June. At this time they move away from their matriarchal groups. A

concentration of births in the early afternoon was detected, coinciding with the

minimal activity of predators in the area. Mothers groom their offspring and ingest the

birth remains to prevent the attraction of predators. During the first days of life fawns

remain hidden keeping motionless.

KEY WORDS:

Dama dama, antipredator strategy, carving time, maternal behaviour.

Introduction

Materials and methods

139

140

Resulrs

143

Discussion

145

146

147

Acknowledgements

References

iNTRODUCTION

The fawns in many species of ungulates are specially liable to suffer from

predation during their first days of life. However, only a few works exist about the

mechanisms of developing an antipredator strategy at calving time, probably due to

the difficulty to observing mothers and their young at birth and during the days

immediately after birth.

Mothers and newborn young in those species use a ehiden> strategy (elk,

ALTMANN 1932; fallow deer, GILBERT 1968; Coke’s bartebeest, GosLiNG 1969;

bontebok, DAvID 1973, 1975; pronghorn, KITCHEN 1974; red deer, GIJINNESS et al.

1978; red buck, IRBY 1979). The species of these groups are basically classified as

*cbidero or ((followers> depending on whether the newborn lie concealed for their first

few clays or actively follow their mothers (LENT 1974, RAI.i.s et al. 1986). While

<<following>> has been viewed as a strategy for avoiding predators in open habitats,

hidinga is thought to reduce predation risk in closed habitats (LENT 1974, ESTES &

ESTES 1979).

As to the behaviour of fallow deer during the calving season, on the basis of the

studies we have conducted to date (ALvA.aEz et a!. 1975, BitAzA et al. 1988, SAN Jose

1988, BItizA & SAN Jose 1989), we may classify fallow deer in principle as ehider>’

since the young remain hidden the first days after birth and are only visited

periodically by their mothers, mainly to feed. Nevertheless, morphological, ecological

and behavioural aspects, which decide this assignment, have not been evaluated

quantitatively up to now. The aim of our study was to evaluate some of these aspects

in mothers and fawns during the calving season and to discuss the results in relation to

the antipredator strategies developed by this species and the physical characteristics

of the habitat.

MATERiALS AND METHODS

Observations included in this paper were carried out at Doñana National Park from 1982 to

1987. In this National Park of 73,000 ha (Fig. I) situated at the mouth of the river Guadatquivir,

the wild fallow deer population occupies an ecotone zone which corresponds to the transition

between the xerophyric schrub and the marshland (BRAZA 1975). In this ecorone we distinguish

between the following biotopes (according to ALLIER er al. 1974, and AGuIr.AR AMAT et al. 1979)

(Fig.1):

a) marshes: characterized by a strong seasonal dependence and made up of species like

Salicornia ramosissima, Arthrocnemum sp. and Scispus maritimus;

bI rush areas: form a mosaic wits pastures at the marshland borders and present a dominant

vegetation of macus marit&nus;

c) wet meadows: areas of pastures which are occasionally flooded and basically characterized

by the association of Amzena gaditana and 44sphodelus aestivus;

d) dry meadows: have a lower level of the subterranean water and present a characteristic

association of the species Urinea maritima and Anthemis cotula;

e) bracken areas: areas with a dense plant cover where the species Pseridium aquilinum

dominates;

f) schrubland: is made up of vegetation which colonized stabilized sands and is basically

characterized by species like Halirnium halimifolium, Cistus libanotis, Erica scoparia, Calluna vulgaris

and Stauracanthus genistoides, among which some isolated cork oaks (Quercus suber) are found.

At present, the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardina) is the only predator able to kill half-grown deer in

Doñana and, as we know, the lynx has very little influence on the early mortaliry of fallow deer

fawns (BELTRAN et al. 1985). Of other potential predators of f allow deer calves (fox, genet,

ichneumon, wildboar, Imperial eagle) rhe analyses do not reveal significant deer presence in their

diet (VENERO 1982, PAL0MARE5 1986, RAu 1988, FERRER 1989).

During 4 years (1983-1986), from the 25th of May to the 20th of June we conducted a census

by car at least once a week a fraction of the ecotone area which measured 5.5 km long and 1.5 km

wide (Fig.1).

Generally two observers record the number of solitary females (animals char were ar least 50

away from any other fallow deer). The proportion of solitary females was calculated with respect ro

the rotal number of females present in the area the same day.

The mean population size during the period 1983-1986 was 264.44 (* 7.89) deer wirh a mean

total number of females of 123.92 (±6.45). The mean calf-ratio was 60.37 (±2.05) (from BRAZA et

al. 1990).

The rutting season takes place during the first fortnight of October (BRAZA er al. 1986).

intipredator behaviour in fallow deer

ri

141

Area of Census

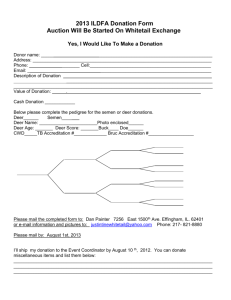

Fig. 1. Doñana National Park and study area (above). The main biotopes considered in the study arc

roportion ol the ecorone zone (below).

—

C. San José and F. Braza

142

198a

>

Ct

1984

0

U)

0

1985

30

-

20

10

L

I

25

May

Fig. 2

5

15

June

P

1986

I

25

5

July

Variations in the percentage of solitary females

Females give birth to a single fawn at the end of spring (BRAZA er al. 1988), after a gestation period

o 236 days (SAN Jos 1988),

During the calving season, in the area of census we searched daily to localize newborn fawns.

This was done on foot and sometimes counting on the assistance of a vehicle or a guard on

Antipredator behaviour in fallow deer

143

horseback. When we found a fawn we recorded all the environmental characteristics of the place

where it was hidden as well as the behaviour shown by the mother (if nearby) and the fawn at our

approach. Once captured the fawn was marked and measured (BRAZA et aI. 1988, SAN josI et al.

1989).

When it was not possible to detect the moment of birth we used various criteria to estimate

the condition vnewbornn, e.g. the presence of remains of the placenta, the still moist fur of the

fawn, the umbilical cord’s degree of healing, the hardening of the hooves and the presence of

cartilage on their points. These criteria have frequently been used to determine the age of newborn

fawns of other deer species (i.e. HAUGEN & SnAKE 1958).

Finally, in order to make more detailed observations, we followed in a ‘main observation area’

(aprox. 150 ha) the movements of the pregnant females. This control was carried out by means of a

binocular telescope (20(40) x (80(500) from a 30 m high observation tower continually from dawn to

nightfall.

We used non parametric statistics (SIEGEL 1956) to evaluate the level of significance of the

results.

RESULTS

A sudden increase in the proportion of solitary females was observed each year at

the beginning of June (Fig. 2). The distributions of solitary females in different years

are coincident (83 X 84, 84 X 85, 85 X 86, t = 1; P< 0.01; KendalL Coefficience of

Concordance). Only 108 birth dates of the 190 fawns captured could be known with

precision. The peak of solitary females coincides with the average date of birth

estimated. With the exception of 1982, with a mean date of birth the 5th of June, for

the rest of the years (1983-1987) most of births occurred within the 3 first days of

June: 1=1 (±3.7), isiS (±3.8), *=3 (±2.2), Yc=2 (±3.8) and i=2.5 (±4.3)

respectively.

In 41 cases it was possible to record exactly the time of birth. From these cases

we could calculate the average hour which is 14:16 (± 3.16). Most births (x = 25.54;

P’cO.OOi) were detected between 15:00 hr and 17:00 hr (Universal time) (Fig.3).

In all the births observed in their entirity (n = 20), the mother turns towards the

fawn, which Ties on the ground immediately after birth, and starts to lick it actively,

removing and ingesting the amniotic membranes which still cover the young. Finally,

D

0

C?

cy

CC

C

C)

C.)

a)

3

—

Distribution of births over the day’ight hourt (Universal time)

C. San José and F. Braza

144

rush

marsh

dry meadow

‘wet meadow

Ei

schrub

bracken

Habitat preference shown by femaLes for

Fig. 4.

hiding their fawn (n = 190).

the female ingests the newborn’s faeces. The newborn fawn has a dark brown coat

with white speckles on its back, the belly being entirely white. Its colour gets

progressively lighter in the course of the 1st week of life.

During the first days of life the fawn lies hidden. Its mother lies down some

metres off or goes away to join a group or to graze alone. The biotope of the hidding

place was not selected randomly (xi = 511.45; P<0.001). Most of the fawns

captured were found in a rush area Cx? = 467.46; P<O.0O1) (Fig.4). The fawn

remains motionless and adopts the typical flat-on-the-ground posture, frequently

curled up totally concealing its extremities and head, although the tendency to run

away when a person is approaching rapidly is correlated with the fawn’s age (r I;

P<0.001) (Fig. 5), increasing and surpassing a probability of 50% from the 3rd day

of life.

01190 fawns captured, for 89 it was possible to observe the mother’s behaviour

when we approached the fawn. In 76% of all cases the female went away from the

place where the young was hidden. In 28 cases the female stayed near the place where

the young was being marked at an average distance of 72.5 m (±45.2).

/

no flight

Itighi

lawn

Eig. 5.

age

(days)

TemporaL variation in the fawn’s reaction at the approach of a person on foot

Antipredator behaviour in fallow deer

145

When analysing the fawns’ and mothers’ behaviour in the main biotopes

(marshes, rush areas and meadows) the tendency was similar; so, the flight probability

by fawns younger than 4 days was significantly low (*=0.12; SD=0.12; x

5.44;

P<0.05, yJ = 14.74; P<O.O1 and Ic = 12; Pc 0.01 repectively); the mother’s flight

tendency was high in the three biotopes (* = 0.74; SD = 0.36) but due to the small

11; P<o.01).

sample it was significant only for rush areas (x?

Finally, counting on 13 cases of fawns ohserved daily, the average date of

integration into the group was calculated. The criterion being the age of the young

when seen in a group for the second time. This value was of 13.61 days (±4.31).

DISCUSSION

Most of fallow deer births take place in Doñana during the first fortnight of

June. In this characteristic the population coincides with most deer populations in

temperate areas presenting a reproductive period which is markedly seasonal and

extraordinarily synchronized (Vos 1960, MITCHELL & LINCOLN 1973, BERGERUD

1975, CLUTTON-BROCK & GUINNESS 1975).

Two general hypothesis are invoked to explain birth synchrony: (i) optimal

timing with respect to season may enhance the survival and growth of offspring as

well as the survival and future reproductive success of the mother (DAUPHINE &

MCCLURE 1974, BUNNELL 1980, DUNBAR 1980, CLUTTON-BROCIC et al. 1982, RUTBERG 1987) and (ii) females may synchronize births in order to reduce predation on

newborns either by satiating or confusing predators (DAUPHINE & MCCLURE 1974,

EsTEs & ESTES 1979, LOTT 1981, BERGERUD et a!. 1984).

With respect to predators, as already mentioned in the Introduction, at present

there are no large predators in the area and there is only the lynx (Lynx pardina) to be

mentioned, which attacks young individuals in autumn and winter, affecting mortality

rates to a minimum degree (DELIBES 1980, BELTRAN et al. 1985). However, until the

forties there were wolves (Canis lupus) living in Doñana; so, predation was an

important force selecting for breeding synchrony in fallow deer.

Furthermore, the cycle of forage availability, in an area like Donana with a very

short spring and a very dry summer, is also probably an important factor selecting the

time of the calving season. The fact that none of the offspring of late breeding

survived the summer seems to confirm this hypothesis. As in other ungulate species

(i.e. FESTA-BIANCHET 1988) inadequate nutrition is suggested as the cause of mortality

of late newborn calves.

At Doñana a peak of births has been detected coinciding with the period of

minimal diurnal activity of predators in the area (DELIBES 1980, ALVAREZ et al. 1983,

PALOMARES 1986, BELTRAN 1988, RAU 1988). A similar diurnal birth distribution has

been described for other fallow deer populations (CHAPMAN & CHAPMAN 1975,

STERBA & KLOSAK 1984) and for other ungulate species (E5TEs 1966, GOSLING 1969).

ESTES (1966) suggests that the morning peak allows the calves to gain coordination

before night fall, when predators are more active, but, since we have no data from

nocturnal observations, in our case it is not possible hypothesize.

The rapid removal of the placenta by placentophagia also lessens the possibility

that predators will be attracted to the slowly-developing calf. In some species a

diurnal distribution of breeding has been interpreted as a possible thermal regulation

C. San José and F. Braza

146

(Len 1981) but we think that this could be less adaptative in Doñana where the

mean minimal temperature itt May-June never falls bellow 10 OC in June

(i=z12.51*1.72 °C during the period 1983-1986).

The efficiency of *clying-outn as an antipredator behaviour is increased by the

initial cleaning of the fawn and by the mother consuming his faeces. These factors

reduce the chance of predator detecting a calf by its smell. This behaviour has been

reported for many ungulate species (GOSLING 1969, ESPMARK 1971, JACKSON et al.

1972, KITCHEN 1974, AUTENRIETH & FICHTER 1975, GUBERNIK 1980, TRILLMICH

1981, SADLEIR 1984).

On the basis of behavioural aspects of antipredator tactics of fallow deer during

the calving season, these species could be classified as <<hider since the newborn lie

concealed for their first few days of life. Accompanied by the concealment of young

calves, the isolation of the female reduces the chance of predation by making

detection by predators more difficult. This behaviour is usually shown by species that

calve on shrublands which vegetation provides a good concealment (ALTMANN 1963,

HAWKINS & KLIMSTRA 1970, JACKSoN et al. 1972, Wmm et al. 1972, HEIDEMANN

1973, MEIER 1973, CHAPMAN & CHAPMAN 1975, CLUTTON-BROCK & GUINNESS 1975,

NELSON & MEal 1981, OZOGA & VERME 1986). Females of species such as wildebeest

that calve on short-grass areas which offer less conceal, do not seek isolation for

parturition and there is no lying-out behaviour (ESTES 1966). In Doñana, fallow deer

have adapted a <<hiden> strategy to an open habitat, selecting the rush areas as the

biotope that offers the highest cover, and then displaying a typical thiders. behaviour

as shown by other fallow deer living in forests (GanERT 1968, CHAPMAN & CHAPMAN

1973).

On the other hand, the cryptic colour of the fallow deer newborn calves and the

particular position that they adopt lying-out could be interpreted as a complete

strategy of camouflage (TINBERGEN et al. 1967) and permits an understanding of the

motionless behaviour displayed in the open biotopes (marshes and meadows).

Furthermore, the success of the <hider, strategy in ungulates depends in part on

the mother’s habitity to minimize the information she transmits about her young’s

hiding place while remaining close enough to distract or drive away a predator

(ALTMANN 1963, LANGMAN 1977, MACCONNELL-YOUNT & SMITH 1978, PRATT &

ANDERSON 1979, TRUE’rr 1979, STEIGERS & FLINDERS 1981, BYERS & BYERS 1983).

At the approach of a potential predator (a person on foot) most fallow deer mothers

run away from the place where the young is hidden, attracting the attention of the

predator by their flight.

Finally, the effectiveness of lying-out in a very young calf depends on a flight

distance of almost zero (TINBERGEN et al, 1967, GOSLKNG 1969). A predator may then

pass close by without the calf revealing its presence by flight. In contrast, a few days

later, fallow deer calves jump and run away when approached to within a few metres.

This is probably correlated with improved chance of escape from predators by flight.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Comislén Ioterininisterial de Ciencias

and the Junta de Andalucia.

y

TecnologIa (C1CYT)

Antipredator behaviour in fallow deer

147

REFERENCES

AGIJILAR AMATJ., MONTES C., RAMIREZ L. & TORRES A. 1979. Pargue Nacionat de Doñana. Mapa

ecoidgico.

Madrid: Instituto para Ia Conservacio’n de La Naturaleza.

ALLIER C., GONZALEZ BERNALDEZ F. & RAMIREZ L. 1974. Donana. Mapa ecologico. Sevill.a: Estacidn

Biolc5gica de Doiiana (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientIficas).

M. 1952. Social behavior of elk, Cervus canadensis nelsoni, in the Jackson Hole area of

Wyoming. Behaviour 4: 111-143.

ALTMANN M. 1963. Naturalistic studies of maternal care in moose and elk, pp. 233-253. In:

Rheinfold ML., Edit. Maternal behavior in mammals. London: Rheinf old H.L.

ALVAREZ F.) BEAm F., AZCARATE T., AGUILERA E. & MAaTIN R. 1983. Circadian rhythms in a

vertebrate community of Doñana National Park. Antis XV Congreso Internacional Fauna

Cinegdtica Silvestre 15: 379-387.

ALVAREZ F., BRA7.A F. & NORZAGARAY A. 1975. Etograma cuantificado dcl game (Dama dama) en

libertad. Doilana Acres Vertebrata 2: 93-142.

AUTENRIETSI R.E. &. FJCHTER E. 1975. On the behavior and socialization of pronghorn fawns.

Wildlife Monographs 42: 1-11.

BELTRAN j.F. 1988. Ecologia y conducta espacio-temporal dcl lince ibérico (Lynx pardina) en ci

Parque Nacional de Doñana. Tesis Doctora4 tlnivenidad de Sevilla.

BELTRAN J.F., SAN Josii C., DELIBES M. & BRAZA F. 1985. An analysis of Iberian lynx predation

upon fallow deer in the Coto Doñana, SW Spain. Proceedings of the XVII International Congress

of Game Biologists 17: 173-181.

BERGERUn A.T. 1975. The reproductive season of Newfoundland caribou. Canadian Journal of

Zoology 53: 1213-1221.

BERGERUn A.T., BUTLER 11.E. & MILLER DR. 1984. Antipredator tactics of calving caribou:

dispersion in mountains. Canadian Journal of Zoology 62: 1566-1575.

BRAZA F. 1975. Censo del gamo Dama dama) en DoEana. Naturalia Hispdnica 3: 1-27.

BRAZA F., GARCIAJ.E. & ALVAREZ F. 1986. Rutting behaviour of fallow deer. Acta Theriologica 31:

467-4 78.

BRAn F. & SAN Jos C. 1989. An analysis of mother-young behaviour of fallow deer during

lactation period. Behavioural Processes 17: 93-106.

BRAZA F., SAN Jost C. & BLosa A. 1988. Birth measurements, parturirion dates and progeny sex

ratio of Dama dama in Doñana. Journal of Mammalogy 69: 607-610.

BRAZA F., SAN Josh C., BLOM A., CASES V. & GARCIA j.E. 1990. Population parameters of fallow

deer at DoEana National Park (SW Spain). Acta Theriologica 35: 279-290.

BUNNELL T.L. 1980. Factors controlling lambing period of Dali’s sheep. Canadian Journal of Zoology

58: 1027-1031.

BIERS J.A. & BIERS K.Z. 1983. Do pronghorn morhers reveal the locations of their fawns?

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 13: 147-156.

CHAPMAN D. & CHAPMANN N. 1975. Fallow deer (Dama dama). Lavenham, Suffolk; Dalton T.

CLUnON-BROCK T.H. & GUINNESS F,E. 1975. Behaviour of red deer (Cervus elaphus) at calving

Lime. Behaviour 55: 286-300.

CLunoN-BR0CK T.H., GUINNESS F.E. & ALBON S.D. 1982. Red deer: behaviour and ecology of two

sexes. Edinbuh: Edinburgh Vnivenity Press.

DAUPHINE T.C. & MCCLURE R.L. 1974. Synchronous mating in Canadian barren-ground caribou.

Journal of Wildlife Management 38: 54-66.

DAwn J.H.M. 1973. The behaviour of bontebok, Damaliscus dorcas dorcas (Pallas 1766), with special

reference to territorial behaviour. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 33: 38-107.

DAvmJ.H.M. 1975. Observations on mating behaviour, patturition, suckling and the mother-young

bond in the bontebok (Damaliscus dorcas dorcas). Journal of Zoology, London 177: 203-223.

DELIBES M. 1980. Feeding ecology of rhe Spanish lynx in the Coto Doftana. Acta Theriologica 25:

309-324.

DUNBAR R.J.M. 1980. Demographics and life-history variables of a population of gelada baboons

Theropithecus gelada. Journal of Animal Ecology 49: 485-506.

ALTMANN

C. San José and F. Braza

148

ESI’MkRK Y. 1971. Mother-young relationship and ontogeny of behaviour in reindeer (Rangifer

tarandus L.). Zeitschrif I für Tierpsychologie 29: 42-81.

ESTES RD. 1966. Behaviour and life history of the wildebeesr (Connochaetes taurinus Burchell).

Nature 212: 999-1000.

ESTES RD. & E5TF,s R.K. 1979. The birth and survival of wildebeest calves. Zeitschrift für

Tierpsychologie 50: 45-95.

FERRER M. 1989. El águila imperial. Base bibliografica de especics amenazadas. Sevilla: Junta de

1ndalucia, Agencia del Medio Ambiente.

FEST&-BI&NCHET M. 1988. Birthdate and survival in bighorn lambs (Ovis canadensis). Journal of

Zoology, London 214: 653-661.

GILBERT B.K. 1968. Development of social behavior in the fallow deer(Dama dama). Zeitschrift für

Tierpsychologie 25: 867-876.

L.M. 1969. Parturition and related behaviour in coke’s harrebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus

co/eel Gunther). Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 6: 265-286.

GUBERNIK D.J. 1980. Maternal imprinting or maternal dabellingm in goats? Animal Behaviour 28:

124-129.

GuINNESS FE., GIBSON R.M. & CLUTTON-BROCK Ti-I. 1978. Calving time of red deer (Cerr’us

elaphus) on Rhum. Journal of Zoology, London 185: 105-114.

FIAUGEN AD.& SPEATCE W.D. 1958. Determining age of young fawn white-railer deer. Journal of

Wildlife Management 22: 3 19-321.

HAwKINS RE. & KLIMSTRA W.D. 1970. A preliminary study of the social organization of whitetailed deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 34: 407-419.

I-IEI0EMANN G. 1973. Zur Biologie des Damwildes (Cervus dama L 1758). Hambmg & Berlin: P.

Parey.

itaY L.R, 1979. Reproduction in mountain red-buck Redunca fulvoruf ala. Mammalia 43: 191-213.

ACKSON R.M., WHITE M. & KNOWLTON F-F. 1972. Activiry patterns of young white-tailed deer

lawns in South Texas. Ecology 53: 262-270.

(ITCHEN D.W. 1974. Social behavior and ecology of the pronghorn. Wildlife Monographs 38: 1-96.

ANGMAN V.A. 1977. Cow-call relationships in giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis giraf-fa). Zeitschrift für

Tie,psychologie 43: 264-286.

£NT P.C. 1974. Mother-infant relationships in ungulates, pp. 14-55. In: Geist V. & Walther P.R.,

Edits. The behaviour of ungulates and its relation ro management. Moges, Switzeland:

International Union for Conservation of Nature.

OTT D.F. 1981. Sexual behavior and intersexual strategies in American bison. Zeitschrift für

Tieqsychologie 56: 97-114.

IACCONNELI.-VOUNT E. & SMITH C. 1978. Mule deer-coyote interactions in north central Colorado. Journal of Mammalogy 59: 422-423.

IEIF.R E. VON 1973. Beitrage zur geburt des Damwildes (Cervus dama L.). Zeitschrift für Saugetierkunde 38: 348-373.

IITCHEL B. & LINCOLN G.A. 1973. Conception dates in relation to age condition in two populations

o1 red deer in Scotland. Journal of Zoology, London 171: 14 1-152.

IELSON M.E. & ME.CII L.D. 1981. Deer socialization and wolf predation in Norrheastern Minnesota. Wildlife Monographs 77: 1-47.

‘ZOGA JJ. & VERME L.J. 1986. Relation of maternal age to fawn-rearing success in white-tailed

deer. Journal of Wildlife Management 50: 480-486.

SLOMARES F. 1986. Ecologia de Ia gineta y del meloncillo en el Parque Nacional de Doñana. Tesis

de Licenciatura, Universidad de Granada.

{ATT D.M. &ANDERSON Vii. 1979. Giraffe cow-calf relationships and social development of the

calf in the Serengeti. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 51: 233-251.

&LLS K., KRANZ K. & LUNDRIGAN B. 1986. Mother-young relationships in captive ungulates:

variability and clustering. Animal Behaviour 34: 134-145.

tu J. 1988. Ecologia del zorro, Vulpes vulpes, en Ia Reserva Biolégica de Donana, Iluelva, SO

España. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Sevilla.

.JTBERG A.T. 1987. Adaptive hypotheses of birth synchrony in ruminants: as interspecific test.

The American Naturalist 5: 693-710.

GOSLING

Antipredator behaviour in fallow deer

149

SADLF.IR R.M.F.S. 1984. Ecological consequence of lactation. Acta Zoologica Pennica 171: 179-182.

SAN José C. 1988. Estrategia reproductiva de las hembras de gamo (Dama dama). Tesis Doctoral,

Unive&dad Complutense de Madrid.

SAN JOSé C., BRAZA F. & VARELA I. 1989. Captura y marcaje de crIas de gamo en ei Parque Nacional

de Donana. Actas IX Bienal Real Sociedad Española Historia Natural 9 (1): 289-301.

SIEGEL S. 1956. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill Book

Co., 312 pp.

STEIGERS W.D. JR & FuNonis J.T. 1981. Mortality and movements of mute deer fawns in

Washington. Journal of Wildlife Management 44: 381-388.

STERBA 0. & KLOSAK IC. 1984. Reproductive biology of fallow deer, Dama dama. B. Female

reproduction. Acta Scientiarum Academiae Scientiarum Bohemoslovacae, Brno 18: 1-46.

TINBERGEN N., IMPEKOvEN M. & FRANCE D. 1967. An experimeot on spacing-out as a defence

against predation. Behaviour 28: 307-321.

TRIu.MIcH F. 1981. Mutual mother-pup recognition in Galapagos fur seals and sea lions: cues used

and functional significance. Behaviour 78: 21-42.

TRIJETT J.C. 1979. Observations of coyote predation on mule deer fawns in Arizona. Journal of

Wildlife Management 43: 956-958.

VENERO J.L. 1982. Dicta de los grandes fitófagos silvestres dcl Parque Nacional de Doflana. Tesis

Doctora4 tiniversidad de Sevilla.

Vos A. nt 1960. Behavior of barren ground caribou on their calving grounds. Journal of Wildlife

Management 24: 250-258.

WIuTE M., KNOWLTON F.F. & BLAZF.NER W.C. 1972. Effects of dam-newborn fawn behavior on

capture and mortality. Journal of Wildlife Management 36: 897-906.