Plea Bargaining - Valdosta State University

advertisement

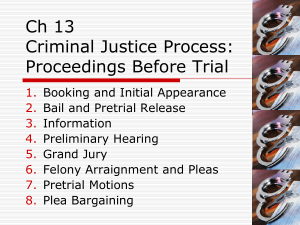

Plea Bargaining The use of prosecutorial discretion within the court system allows the prosecutor the freedom or authority to make judgments based on the existing circumstances as he or she perceives them. It is the job of the Executive Branch to use discretion when dealing with federal laws. However in criminal law, including federal and state levels, it is up to the prosecutors to use his or her discretion. One of the most used forms of prosecutorial discretion is the plea bargain. A plea bargain gives the prosecutor the ability to accept a guilty plea on a lesser charge than that was originally brought. It is estimated that “…over ninety percent of all criminal cases are disposed of through guilty pleas” (Whitebread, 2000). The majority of these guilty pleas were the result of a “…‘plea bargaining’ between the prosecution and the defense, in which the former makes charges or sentencing concessions in exchange for a plea of guilty” (Whitebread, 2000). Although the use of plea bargaining has both a positive and negative side, “…the courts have come to accept guilty pleas and plea bargaining as a necessary and established part of the criminal justice system” (Whitebread, 2000). A plea agreement is usually reached after the prosecution and the defense engage in a discussion regarding the issues and severity of the case at hand. The prosecution will normally offer one or more of the following solutions: “…(1) a reduction in charge; (2) dismissal of other pending charges; (3) a promise to recommend or not contest a particular sentence or range of sentences; or (4) a stipulation that a particular sentence is the appropriate disposition” (Whitebread, 2000). The defendant will then decide whether to take the plea of guilty based on the offer given. There are essentially two types of guilty pleas in which the defendant can plea. The first is the common plea of guilty. The second is a plea of nolo contendere which is “identical to the guilty plea, except that it cannot be used against a defendant as an admission of guilt in a subsequent civil case” (Whitebread, 2000). When a defendant agrees to take a plea bargain and plea guilty they may also be agreeing “…to testify against a co-defendant, forgo asserting certain rights, or provide other benefits to the prosecution” (Whitebread, 2000). In the case of Kirby v. Illinois (1877) the Supreme Court held that “…the Sixth Amendment right to counsel attaches whenever, after the initiation of criminal proceedings, ‘a defendant finds himself faced with the prosecutorial forces of organized society, and immersed in the intricacies of substantive and procedural criminal law” (Whitebread, 2000). The defendant is also “…entitled to counsel during the bargaining process, as well as during arraignment” (Whitebread, 2000). The prosecutor cannot bargain directly with the defendant unless there has been a waiver of counsel. When the counsel does perform the bargaining they are required by the Sixth Amendment to do so effectively. Counsel should also “…carry out sufficient investigation of the case to permit him to advise his client as to various charging and sentencing options. He should also ensure that his client understands the options available” (Whitebread, 2000). The Supreme Court has held that “…failing to fulfill these tasks is not necessarily ineffective assistance of counsel under the Sixth Amendment” (Whitebread, 2000). Hill v. Lockheart (1985) established that in order to prove ineffectiveness of defense counsel, the defendant must show a reasonable probability that, except for counsel’s errors, the defendant would not have plead guilty. Brady v. United States (1970) was a very important case because “...it was the first Supreme Court opinion which explicitly condoned plea bargaining, [and] … it provided the theoretical basis for analyzing the validity of various types of bargains” (Whitebread, 2000). “While indicating that a guilty plea that is ‘compelled’ by the government is invalid under the Fifth Amendment because a defendant is thereby forced to ‘testify’ against himself, it was careful to distinguish between a compelled plea, on the one hand, and a plea which is merely ‘caused’ by a legitimately posed offer” (Whitebread, 2000). McMann v. Richardson (1970) and Parker v. North Carolina (1970) were both ruled on the same day as Brady. They emphasized the difference between “causation” and “coercion” (Whitebread, 2000). These cases established that “…if the coercion leading to a confession also tainted the plea, a valid Fifth Amendment claim would exist. But here the defendants were merely alleging a ‘but for’ relationship between the confession and the guilty plea which did not make out a valid involuntariness claim” (Whitebread, 2000). The Brady case “…did not address the constitutionality of inducements consciously offered by the state to obtain a plea” (Whitebread, 2000). However, the case of Bordenkircher v. Hayes (1978) established that a defendant’s rights are not violated when a prosecutor threatens to re-indict the accused on more serious charges if he or she is not willing to plead guilty to the original offense. The Supreme Court “…reasserted that an action taken by a defendant in plea negotiations passes constitutional muster if it represents a choice among known alternatives” (Whitebread, 2000). The Supreme Court also reiterated the holding in North Carolina v. Pearce (1969) which stated that “… punishing a defendant ‘because he has done what the law plainly allows him to do is a due process violation of the most basic sort’” (Whitebread, 2000). Statutes can also require greater sentencing if no plea is reached. This is shown in the case of Corbitt v. New Jersey (1978) where the defendant could have plead guilty and the judge would have had the choice between sentencing him to 30 years or life imprisonment. However, Corbitt plead not guilty and was given life imprisonment because it was required by the New Jersey state statute. The Supreme Court “…upheld this scheme against a due process claim, concluding that it could not permit bargaining by a prosecutor, as it had in Bordenkircher, ‘and yet hold that the legislature may not openly provide for the possibility of leniency in return for a plea’“(Whitebread, 2000). The case of United States v. Mezzanatto (1995) established that a defendant who wants to plea bargain in federal court can be required to agree that, if he or she testifies at trial, his or her statements during the plea barging negotiations can be used against him or her at trial. In this case there were no negotiation reached and the defendant testified at the trial. However, the prosecution was allowed to use the contradictory statements made at the negotiation meeting to rebut the defendants testimony. The defendant appealed his conviction on three grounds: (1) the right to prevent prosecution use of plea statements is so important to a ‘fair procedure’ that it should be considered unwaivable; (2) allowing such waiver will deter plea bargaining by defendants (who will fear that their negotiation statements might provide the prosecution with rebuttal evidence); and (3) allowing waiver will encourage prosecutorial abuse of the bargaining process (Whitebread, 2000). Santobello v. New York (1971) established that the promise of a prosecutor that rests on a plea of guilty must be kept in a plea bargaining agreement. The Supreme Court discussed “…the many benefits associated with disposing of charges after plea discussions, but added that the utilization of this process presupposes fairness in securing agreement between an accused and a prosecutor”(Whitebread, 2000). The Court stated in its conclusion that “…‘when a plea rests in any significant degree on a promise or agreement of the prosecutor, so that it can be said to be part of the inducement or consideration, such promise must be fulfilled’” (Whitebread, 2000). The defendant is also required to fulfill their end of the bargain as established in Ricketts v. Admason (1987). The Ricketts v. Admason held that the defendant is required to keep his or her side of the bargain to receive the promised offer of leniency, because plea bargaining rests on an agreement between the parties. When a defendant pleads guilty it is the duty of the judge to ensue that the plea meets certain constitutional and statutory standards. Boykin v. Alabama (1969) established that the defendant must make an affirmative statement that the plea is voluntary before the judge can accept it. The Supreme Court also felt that it was vital for the judge to conduct a direct interview with the defendant in order to ascertain the plea’s voluntariness as seen in McCarthy v. United States (1969). The requirements that are required by the judge to address the defendant are to ensure: (1) that the plea is ‘intelligent’ i.e., that the defendant understands the elements of the plea and any associated bargain; and (2) that the plea is ‘voluntary,’ i.e., that the defendant was not coerced into the plea. Additionally, to ensure that the plea is ‘accurate,’ the judge should make some effort to ascertain (3) that there is some sort of factual basis for the plea (Whitebread, 2000). North Carolina v. Alford (1970) was another case that helped mold the regulations on plea bargaining. This case established that accepting a guilty plea from a defendant who maintains his or her innocence is valid. After reviewing all the information on plea bargaining I believe that it would be hard for a prosecutor to carry out all of his or her necessary functions without such discretionary powers. The use of plea bargaining benefits the defendant in ways such as lessening the time and money spent on defending themselves at trial, lessens the risk of a harsher punishment, and avoids the publicity that is sometime involved with a public trail. The prosecution also benefits by saving time and money on a potential lengthy trail. The court system in general is the one that receives the largest benefit of plea bargains. The system is already over burdened with cases and if there were no plea bargains, the courts would have to conduct a trial on every crime that was charged. I believe that the use of the plea bargain is useful to all parties involved and the system should only change if there is some way in which it could become better. Works Cited Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 U.S. 357, 98 S.Ct. 663 (1978). Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238, 89 S.Ct. 1709 (1969). Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742, 90 S.Ct. 1463 (1970). Corbitt v. New Jersey, 439 U.S. 212, 99 S.Ct. 492 (1978). Hill v. Lockheart, 474 U.S. 52, 106 S.Ct. 366 (1985). Kirby v. Illinois, 406 U.S. 682, 92 S.Ct. 1877 (1972). McCarthy v. United States, 394 U.S. 459, 89 S.Ct. 1166 (1969). McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759, 90 S.Ct. 1441 (1970). North Carolina v. Alford, 400 U.S. 25, 91 S.Ct. 160 (1970). North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711, 89 S.Ct. 2072 (1969). Parker v. North Carolina, 397 U.S. 790, 90 S.Ct. 1458 (1970). Ricketts v. Admason, 483 U.S. 1, 107 S.Ct. 2680 (1987). Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S. 257, 92 S.Ct. 495 (1971). United States v. Mezzanatto, 513 U.S. 196, 115 S.Ct. 797 (1995). Whitebread, C.H., & Slobogin, C. (2000). Criminal Procedure An Analysis Of Cases And Concepts. New York: Foundation Press.