Australia`s Native Vegetation Framework

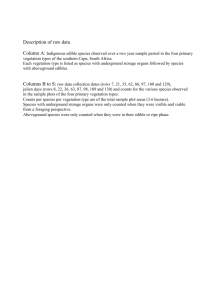

advertisement